Texas Electric Railway: Map, History, Timetables

Published: February 2, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Texas Electric Railway (TER), often an overlooked component of the early 20th-century transportation revolution in the United States serves as a fascinating case study of the evolution and eventual decline of electric interurban railways.

Established against the backdrop of the Progressive Era, the TER was former in 1916 from two predecessor systems, a period marked by rapid technological advancements across America.

At its peak the Texas Electric operated a 230-mile system via three separate divisions. The system was generally profitable until the end of World War II when it declined steeply and was abandoned entirely in 1948.

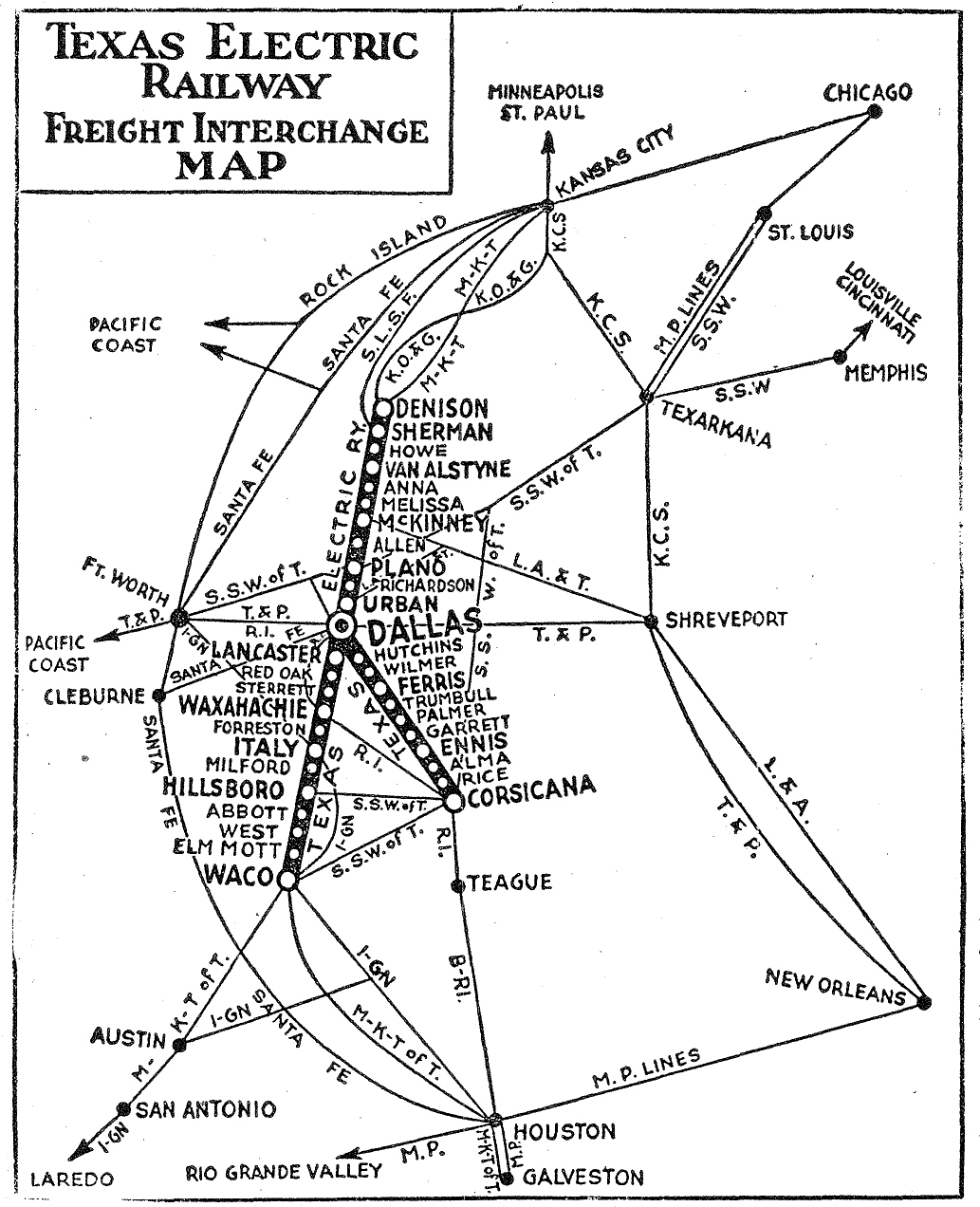

System Map (1940)

Origins

The origins of the TER are inexorably linked to the economic growth and burgeoning population of Texas. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Texas witnessed significant industrialization and urbanization, prompting the need for improved transportation infrastructure.

This demand was particularly pressing in the northern and central regions of the state, where cities like Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, and Denison were experiencing rapid growth.

The Texas Electric property initially comprised two interconnected entities: the Texas Traction Company and the Southern Traction Company. The former completed its line on July 1, 1908, extending 66 miles north from Dallas to Sherman, with an additional 11-mile stretch connecting Sherman to Denison.

It was originally constructed in 1901 by the Denison & Sherman Railway and was incorporated into the Texas Traction system in 1909. The tracks were laid on private right-of-way and ran parallel to, and frequently adjacent to, the Houston & Texas Central (Southern Pacific) line.

Established in 1912, the Southern Traction Company constructed two lines: a 97-mile route to Waco via Waxahachie and Hillsboro and a 52-mile line to Corsicana through Ferris and Ennis. These lines were constructed between 1912 and 1913, commencing operations on January 1, 1914. The two companies consolidated in 1916, forming the Texas Electric Railway.

These systems were forerunners in deploying robust arched-roof steel cars, identified by their distinctive arched windows, which could attain speeds up to 60 mph and function in either single or multiple-unit (MU) configurations.

The trains typically operated as single units, except during peak travel periods. While the lines were constructed to rigorous specifications, the cars transitioned onto streetcar tracks to access the downtown Dallas terminal.

A new terminal was constructed for the interurban lines by the Dallas city system, which was not directly affiliated with the TER.

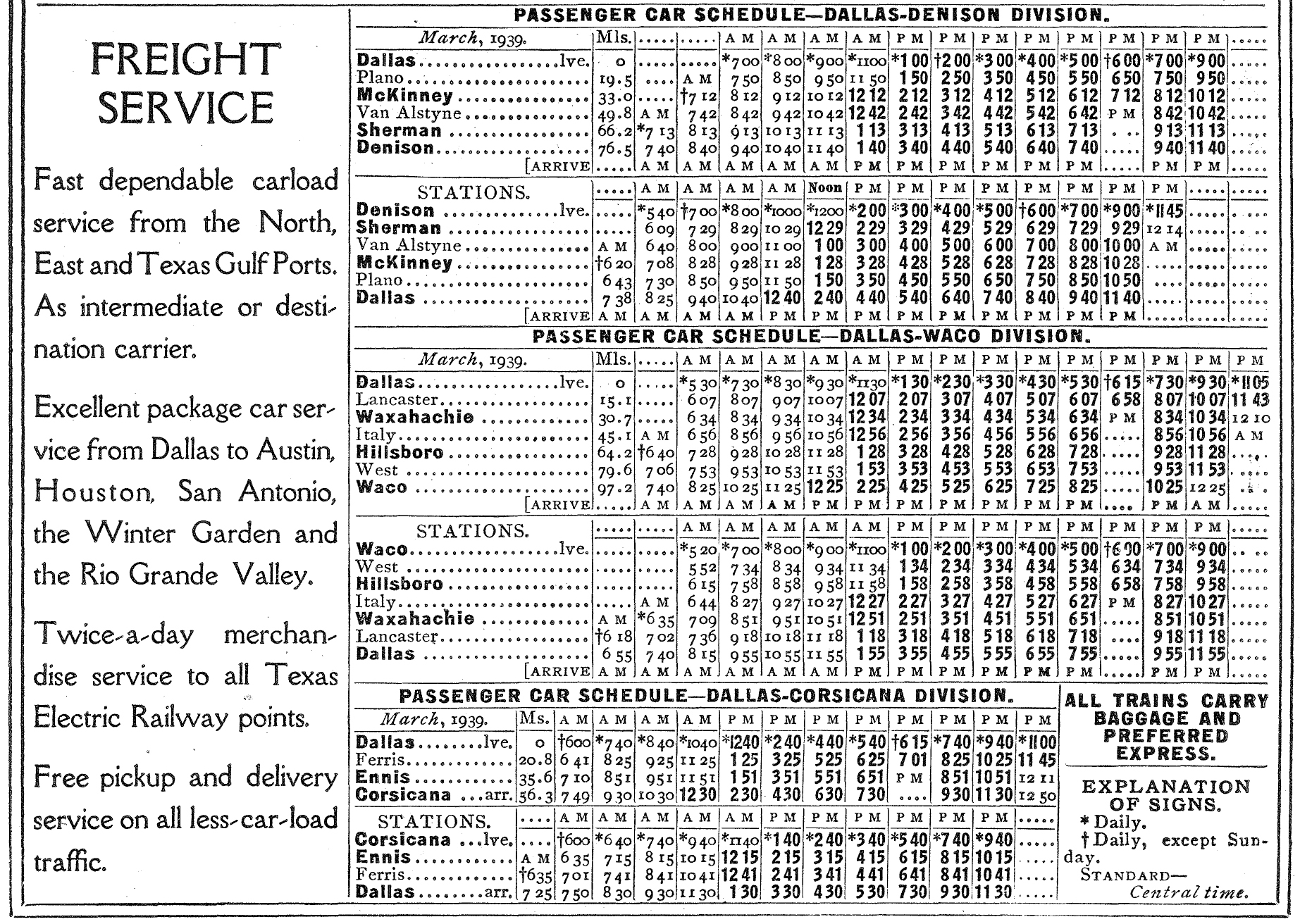

For many years, the railway maintained hourly train schedules across all three lines, in addition to providing extensive service between Sherman and Denison. Some of the routes were express services, known as Bluebonnets, which only stopped in towns and generally maintained speeds of 50 mph.

Although some trains were discontinued around 1930, the line continued to provide essentially hourly service post-World War II, with minimal omissions during midday.

Texas Electric was among the few interurbans to operate Railway Post Office (RPO) service, with the TER being one of the last to do so. While the company did not engage in the carload freight business until 1928, it effectively developed a substantial freight volume, which helped mitigate the decline in passenger traffic.

At its peak, the Texas Electric Railway operated 230 miles, linking Dallas with Denison to the north and Waco to the south, and spanning various smaller communities in between. The system was broken down into the following divisions:

- Dallas-Denison Division (76.5 miles)

- Dallas-Waco Division (97.2 miles)

- Dallas-Corsicana Division (36.3 miles)

The system originated as a local initiative in Dallas, orchestrated by the J. F. Strickland Company, and operated independently of any power, transit, or other utility organizations.

Leadership was maintained for numerous years by J. P. Griffin, a prominent figure within the American Electric Railway Association. Financially, the TE was notably one of the most prosperous interurbans, distinguished as one of the rare ventures that largely justified its investment.

Importance

The economic impact of the TER was profound. By facilitating the rapid movement of people and goods, it helped spur the growth of commerce and industry along its route.

Farmers and merchants could access larger markets, while urban residents could travel more easily for business or leisure. Furthermore, the TER played an essential role in democratizing travel, making it accessible to broader segments of the population.

Success

Despite a decline in gross revenue from a peak of over $3 million in 1921, the operating ratio remained approximately 60% throughout the 1920s, and the return on investment exceeded 4% - a number almost unheard of among interurbans.

Consequently, the company's financial status was decidedly stronger than that of the industry average. Fixed charges were sufficiently covered, preferred stock dividends were distributed up to 1926, and dividends for common stock were occasionally paid.

Decline

The rise of the automobile and the development of an extensive network of highways gradually rendered interurban lines less economically viable. Additionally, the Great Depression dramatically reduced passenger numbers and revenue, putting financial strain on these systems.

The depression led to a significant decrease in revenues, prompting the company to enter receivership in 1931, and subsequently reorganize on January 1, 1936.

Despite this, the TER avoided operating deficits, and with the advent of World War II, it experienced a revival; notably, in 1944, after-tax net income was recorded at $510,000, derived from a gross income of $2,216,000.

In 1941, the lightly trafficked Dallas-Corsicana Division was abandoned, as it was argued that its deficits undermined the financial health of the entire system.

World War II temporarily revitalized the TER, as gasoline rationing and increased industrial production brought renewed demand for public transportation. However, this resurgence was short-lived.

Following 1945, there was a marked decline in traffic as automobile and truck usage increased, resulting in the 1947 gross revenue being half of that in 1944.

In December 1948, the entire system was ultimately discontinued - in part, due to a tragic head-on collision between two passenger cars, which resulted in numerous fatalities.

Timetables (1940)

The TER's closure symbolized the broader decline of interurban rail across America, as it succumbed to the pressures of a rapidly changing transportation landscape. While the physical remnants of the Texas Electric have largely vanished, its legacy lives on in the historical memory of Texas transportation.

The TER's role in shaping regional development and contributing to the modernization of urban transit is recognized as a significant chapter in the narrative of American industrial innovation.

Ironically, rapid transit systems have made a small comeback in Lone Star State with systems like the TEXRail and commuter systems such as Trinity Railway Express.

Recent Articles

-

Oregon Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 03:11 PM

With its rich tapestry of scenic landscapes and profound historical significance, Oregon possesses several railroad museums that offer insights into the state’s transportation heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 02:56 PM

Today, several museums in North Caorlina preserve its illustrious past, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of railroads with artifacts, model trains, and historic locomotives. -

New Jersey Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 11:48 AM

New Jersey offers a fascinating glimpse into its railroad legacy through its well-preserved museums found throughout the state.