Steam Locomotives (USA): Invention, History, Types

Last revised: November 5, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Steam locomotives are impressive, captivating, ingenious, complex, and dangerous devices all wrapped within a single frame. Nothing else in railroading has ever been quite as alluring.

It was largely responsible for driving the American industrial machine although has its origins in England, with the first patented version credited to Richard Trevithick and Andrew Vivian in 1802.

Its initiation here began in 1826 when Colonel John Stevens showcased his "Steam Waggon" (basically a steam-powered horse carriage) on a small circular track at his estate in Hoboken, New Jersey.

In the succeeding years ever-larger types were conceived to handle increasingly greater demand. The argument persists to this day regarding whose were more impressive, American or British?

Development

Unquestionably, American designs were the most powerful, particularly after the introduction of articulation, which led to enormous variants like the 2-6-6-6 "Allegheny," 4-6-6-4 "Challenger," and 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy."

Today, preserved steam locomotives, both large and small, can be found throughout the country and their sustained popularity has led to numerous restorations. They remain so well-liked that even Union Pacific maintains a small fleet for public relations.

Southern Pacific 4-8-8-2 #4287 (AC-12) totes a few gondolas of scrap metal and a caboose through the yard in Colton, California during 1953. American-Rails.com collection.

Southern Pacific 4-8-8-2 #4287 (AC-12) totes a few gondolas of scrap metal and a caboose through the yard in Colton, California during 1953. American-Rails.com collection.History

The development of the steam engine far predated its use in railroad applications as historian Mike Del Vecchio notes in his book, "Railroads Across America."

The very first railroad-type operation occurred in England during 1630 when wooden rails, upon which wooden cross-ties (or "sleepers") were attached for lateral support, were laid down for the express purpose of handling coal.

This rock would prove vital in the steam locomotive's future development. The first known implementation of iron rails occurred in 1740 at Whitehaven, Cumberland, followed by the flanged wheel's introduction in 1789 at Loughborough, Leicestershire, the concept of William Jessop. The steam engine is attributed to Thomas Newcomen who received a patent for his design in 1705.

At A Glance

It was later improved upon by James Watt in 1769 who realized expanding steam was much more powerful and efficient than Newcomen's condensing version.

He first employed the engine in steamboats, which eventually found its way to the United States where Colonel John Stevens began using it for the same purpose.

Virginian Railway 2-8-2 #430 (Class MB) works local service in Norfolk, Virginia during December of 1954. H. Reid photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Virginian Railway 2-8-2 #430 (Class MB) works local service in Norfolk, Virginia during December of 1954. H. Reid photo. American-Rails.com collection.1800s and the Industrial Revolution

Stevens is also credited with chartering the first railroad in North America when the New Jersey Railroad Company was founded in 1815 (although not actually built until 1832), a future component of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The colonel's recognition did not end there; he also tested the first type of steam locomotive in the United States during 1826 when he showcased his aforementioned "Steam Waggon" on a small circular track at his estate in Hoboken, New Jersey. But, once more, England is recognized as operating the world's first modern steam locomotive.

A Norfolk & Western publicity photo, circa 1943, featuring (left to right) 4-8-4 #604 (J), 2-8-8-2 #2147 (Y-6), and 2-6-6-4 #1212 (A) at Shaffers Crossing, Virginia (Roanoke).

A Norfolk & Western publicity photo, circa 1943, featuring (left to right) 4-8-4 #604 (J), 2-8-8-2 #2147 (Y-6), and 2-6-6-4 #1212 (A) at Shaffers Crossing, Virginia (Roanoke).Trevithick's earliest example went into service in 1804 on the Merthyr-Tydfil Railway in South Whales where it pulled loads of iron ore along a tramway. Two decades would pass before the first contemporary design appeared thanks to George Stephenson.

He was born on June 9, 1781 to a very modest family in the small village of Wylam, Northumberland near Newcastle upon Tyne.

Stephenson may have spent his childhood relatively poor but he quickly recognized the value of education, taking it upon himself to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic.

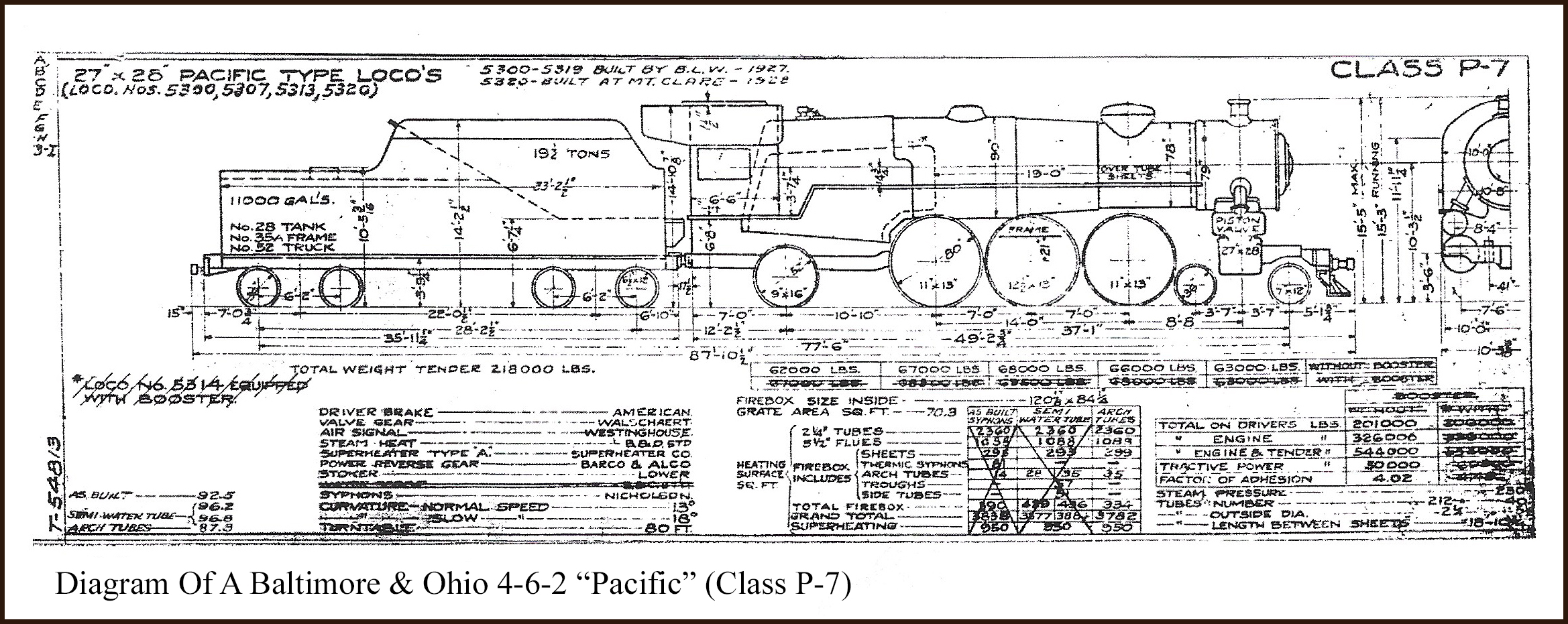

Diagram

In time he became an expert on steam train technology and decided to improve upon the early works of others like Trevithick. In 1814 he designed his very first locomotive for the Killinwood Railway named the Bulcher.

This was followed by a second in February of 1815 and before long Stephenson's durable designs were catching widespread attention.

In 1821, England's first railroad, the Stockton & Darlington (S&D), was authorized through an Act of Parliament to build a 12-mile line intended to connect its namesake towns.

It would once again haul coal, as virtually every other had up until that time. However, the railroad was also envisioned to serve the public, the first of its kind.

According to Brian Solomon's book, "The Majesty Of Big Steam," the S&D entered service on September 27, 1825 when Stephenson's little 0-4-0 #1, the Locomotion, pulled an impressive 34 cars that day.

He, himself, (who was also the company's chief engineer) piloted the locomotive which featured elements of modern designs, a horizontal boiler and vertical stack.

But it was a later Stephenson design that truly carried the steam locomotive's contemporary inner workings. Credit for the 0-2-2 Rocket has often been given to father, George.

However, it was actually a joint effort with son, Robert, through their mutually-owned Robert Stephenson & Company (a builder which supplied locomotives to a number of early American railroads).

This particular unit won the legendary Rainhill Trials held during October of 1829 on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

The competition's purpose, of which four entries took part, was designed to ascertain whether stationary steam engines or moving locomotives were the most economic means of pulling the railroad's trains.

Rio Grande 2-8-2 #1207 arrives at Montrose, Colorado on September 21, 1946. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande 2-8-2 #1207 arrives at Montrose, Colorado on September 21, 1946. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.The Rocket attained a top speed of 29 mph and was easily declared the winner in a landslide performance. As Mr. Solomon notes it featured all of the basic components of the modern steam locomotive including a horizontal "...fire-tube boiler, forced draft from exhaust steam, and direct linkage between the piston and drive wheels."

Early Examples

One of America's earliest transportation companies was the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, envisioned to haul anthracite coal from eastern Pennsylvania to New York City via the Hudson River.

The operation eventually decided upon canals for this purpose although chief engineer John B. Jervis wanted steam-powered locomotives right from the start.

Jim Shaughnessy points out in his book, "Delaware & Hudson: Bridge Line To New England And Canada," that Jervis believed four such contraptions could operate the gravity line's less severe grades.

Rio Grande 2-8-2 #498 (K-37) leads an eastbound freight out of Durango, Colorado along the narrow-gauge San Juan Extension just before freight operations ended during the summer of 1968. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande 2-8-2 #498 (K-37) leads an eastbound freight out of Durango, Colorado along the narrow-gauge San Juan Extension just before freight operations ended during the summer of 1968. American-Rails.com collection.During a trip to England in the summer of 1828, with help from associate Horatio Allen, he ordered one from the Robert Stephenson & Company based from the same plans as the Rocket while three others were built by Foster, Rastrick & Company of Stourbridge.

The Stephenson unit was named America and the first to arrive, unloaded in New York on January 15, 1829.

Union Pacific 4-6-6-4 #3941 and 4-8-8-4 #4024 double-head through Borie, Wyoming on May 14, 1953. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-6-6-4 #3941 and 4-8-8-4 #4024 double-head through Borie, Wyoming on May 14, 1953. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.The noteworthy Stourbridge Lion was delivered on May 13th. In a strange turn of events, only the Lion was actually tested by the Delaware & Hudson. The America made a quick demonstration run in New York on May 27th, as did the Lion a day later on May 28th.

After wowing onlookers in an event that could be argued as the first-ever utilization of steam locomotives on American soil, the duo were shipped up the Hudson to Rondout (near Kingston).

A pair of Pennsylvania K-4s Pacifics double-head on the New York & Long Branch at Bay Head Junction, New Jersey, circa 1949. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Pennsylvania K-4s Pacifics double-head on the New York & Long Branch at Bay Head Junction, New Jersey, circa 1949. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.Unfortunately, due to circumstances never fully understood the America failed to reach the D&H property. The Lion went on to carry out test trials on August 8, 1829, earning it distinction as the first use of a steam locomotive in the United States.

Unfortunately, its ultimate fate was rather unglamorous; it proved too heavy for the track and languished in a shed before finally being scrapped in 1870.

Following its trials American steam technology quickly advanced. On August 28, 1830, Peter Cooper's Tom Thumb famously raced a horse on the fledgling Baltimore & Ohio.

The little one-ton coal-burner, featuring a vertical boiler, lost the bout (while carrying 30 patrons in a train consisting of a single coach) but had nevertheless proved its viability.

According to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum the locomotive was capable of speeds up to 15 mph.

While it did spend a year carrying passengers from time to time it never entered regular service and was later scrapped in 1834 (a replica is on display at the museum, constructed for the B&O's 1927 Fair of the Iron Horse and based from drawings Cooper had provided in 1875).

Since the Thumb was only an experiment, another locomotive was given recognition as the first American-built design to haul a revenue passenger train.

Nearing retirement, Union Pacific 4-6-6-4's #3702 and #3703 meet near Cheyenne, Wyoming in July of 1959. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Nearing retirement, Union Pacific 4-6-6-4's #3702 and #3703 meet near Cheyenne, Wyoming in July of 1959. Richard Wallin photo. American-Rails.com collection.That honor is bestowed upon the South Carolina Canal & Railroad Company's Best Friend of Charleston, built by New York's West Point Foundry, when the 0-4-0 carried a train of paying customers on December 25, 1830.

Unfortunately, the locomotive also earned the sad distinction as being the first to suffer a boiler explosion, which occurred during June of 1831.

As the story goes the fireman became vexed by its constant hissing noise and tightened the safety valve closed (he later died of his wounds). The Camden & Amboy's John Bull, also the work of Robert Stephenson & Company, was another notable early locomotive.

A testament to the high quality craftsmanship the Stephensons incorporated into their product the Bull remained in service from 1831 until 1866.

It was originally designed as an 0-4-0, not unlike their other products from that period. Over time C&A engineers upgraded the unit with several features commonly found on modern variants such as a cow-catcher, lead pilot truck, covered cab, and trailing tender (fuel storage to operate further between stops).

Operation

The steam locomotive is relatively basic contraption. Fuel (originally wood or coal, and then later oil) is fed into the firebox where the resulting hot gas enters boiler tubes, known as flues, which heat the surrounding water to form steam.

This steam is then fed into pistons whereby it expands and drives the locomotive’s rods (horizontal iron/steel shafts attached to the wheels), propelling it forward. The resulting hot gases are then carried into the smoke box where they are funneled towards the smoke stack and out of the locomotive.

As technologies improved wheel arrangements became increasingly larger and more powerful. These advancements over the years made them incredibly complex machines.

The period from 1900 through World War II witnessed the locomotive's zenith. Mr. Solomon notes that the introduction of steel, welding, and improved casting techniques offered stronger designs without increased weight.

There were also component improvements such as better valve gear, larger fireboxes, lengthened boilers, roller-bearings, precision counter-balancing, and feedwater heaters (devices which heated the water before it entered the boiler).

In 1925 Lima Locomotive Works, in conjunction with the New York Central, developed the "Super Power" locomotive utilizing a larger firebox for a more economic use of the boiler.

The testbed unit was a Boston & Albany 2-8-2 (H-10a), given an additional rear axle, and re-classified as A-1. The 2-8-4 demonstrator made a successful test on April 14, 1925 where it out-performed a 2-8-2 within the Berkshire Mountains of northwestern Massachusetts.

Lima, one of the "Big Three" steam builders (others being the Baldwin Locomotive Works and American Locomotive Company), went on to manufacture hundreds of 2-8-4's for various railroads.

Definitions and Terms

Below are many steam locomotive terms that broadly cover steam driven motive power, highlighting everything from different types to specific functions of various locomotive parts.

Also, if you have any questions about the meanings of any of these definitions or simply have more to add that are not covered here please do not hesitate to get in touch with me.

Lastly, I do hope that the below terms and meanings are of help and beneficial use to you, as that is the main reason for providing the information presented here!

All-weather cab: A steam locomotive cab enclosed at the rear to provide the crew with protection from harsh weather. Also called vestibule cabs.

Articulated: A steam locomotive with two sets of driving wheels under a single boiler. Articulated locomotives have wheels arrangements such as 2-8-8-4 or 4-6-6-4. Articulated rolling stock, such as certain types of passenger cars and double-stack cars, share trucks between adjacent car bodies.

Backhead: The rear of a steam locomotive's firebox; located in the cab, it's where many of the locomotive's controls are mounted.

Cab-forward: A type of articulated steam locomotive most commonly found on the Southern Pacific, with the cab located at the front of the locomotive and the smoke stack at the rear.

The locomotive's fuel was oil piped all of the way to the firebox at the front of the locomotive.

The Cab-forward was a brilliant design that allowed train crews to stay ahead and out of the noxious fumes and smoke found in the many tunnels and snowsheds through the Sierras of SP's Sacramento Division.

Camelback: A steam locomotive built through 1927, with the engineer's cab setting astride the middle of the boiler rather than at the rear. A small overhang remained at the rear for the fireman stoking the wide anthracite-burning firebox.

Climax: Type of geared steam locomotive built by the Climax Manufacturing Company featuring a pair of inclined cylinders just behind the smokebox driving a transverse shaft which was geared to a central longitudinal driveshaft that in turn drove all the axles through skew bevel gears.

Compound: A type of steam locomotive that takes the steam after it has partly expanded in one cylinder and pipes it to another cylinder, where it further expands and pushes another piston, before being exhausted out of the smokestack.

Connecting rod: Perhaps the one single component of a steam locomotive that makes it so fascinating it is the large steel arm that transfers motion from the piston to the driving wheels.

Cylinder cocks: Opening on a steam locomotive's cylinders that allow for excess water to be released, which condenses in the cylinders when the locomotive is not moving.

Decapod: A 2-10-0 arrangement of a steam locomotive type.

Displacement: The volume displaced by a complete stroke of the piston.

Doghouse: Nickname for the shelter placed on the tender deck of steam locomotives to house the head brakeman.

Duplex-drive: A non-articulated steam locomotive with two sets of cylinders and drive wheels.

Feedwater heater: In a steam locomotive, a device that pre-heats water from the tender as it is fed into the boiler to make steam.

Heisler: Type of geared steam locomotive built by the Heisler Locomotive Works featuring two cylinders arranged in a "V" under the boiler driving a central longitudinal shaft gear to the outer axle of each truck. Side rods connected the outer and inner axles.

Injector: Device for adding water to a steam locomotive boiler.

Nearing the end of their careers, Union Pacific "Big Boys" and "Challengers" rest in Cheyenne on September 6, 1956. Note the workers washing 4-8-8-4 #4024. J.E. Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Nearing the end of their careers, Union Pacific "Big Boys" and "Challengers" rest in Cheyenne on September 6, 1956. Note the workers washing 4-8-8-4 #4024. J.E. Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.Jawn Henry: Experimental coal-fired steam turbine locomotive, built in 1954 by Baldwin-Westinghouse for the Norfolk & Western Railway.

The locomotive weighed some 409 tons, was rated at 4,500 horsepower, produced 199,000 pounds of tractive effort, and could haul more tonnage on less fuel than convention steam engines, but at lower speeds. The engine was scrapped in 1957.

MacArthur engine: Redesignated name for the Mikado-type (2-8-2) steam locomotives in honor of General Douglas MacArthur. The locomotive was used by a handful of railroads during World War II.

Mallet: A type of articulated compound steam locomotive with two sets of cylinders, rods, and drive wheels under one boiler. The non-swiveling rear engine works at boiler pressure, and the swiveling front engine uses exhaust steam from the rear engine.

Developed by Swiss inventor Anatole Mallet (mal-LAY, but often pronounced MAL-ley in the U.S.), this type of locomotive was substantially bigger than its predecessors, and was popular between roughly 1905-1925.

Mike: Short for a Mikado (2-8-2) steam locomotive.

Pop valve: The safety or pressure release valve on a steam locomotive boiler.

Quarter-locked: Condition of a steam locomotive when it is stopped so that the drive rods are directly aligned with the piston which does not allow for the locomotive to be moved. The two sides of a steam locomotive are "quartered" (one-quarter rotation out of phase with each other) to prevent quarter-locking from occurring.

Radius rod: On a steam locomotive, the small rod that transfers motion from the valve gear mechanism to the valve rod.

Saddle-tank: A steam locomotive which carries its water supply in a tank which straddles the boiler.

Shay: Type of geared steam locomotive desinged by Ephraim Shay and built by the Lima Locomotive Works. The most common of the geared steam engines, it featured a set of vertical cylinders on the right of a boiler offset to the left. The cylinders drove a longitudinal shaft that drove the axles through bevel gears.

Smoke deflector: An object placed on both sides of a steam locomotive's boiler near the smokestack that would create air currents to lift the smoke above the boiler. The purpose of the deflector was to increase the crew's visibility and keep smoke out of the cab.

Superheater: A series of coils containing freshly created steam that pass through flue gasses to increase the temperature of the steam and make it more powerful. Once steam has passed through superheater coils, it adds 25 to 30 percent more power to an engine.

Thermic syphon: In a steam locomotive firebox, a funnel-shaped steel fabrication that connects the bottom of the throat sheet and the crown sheet. Water flows upward through the syphon, connecting the coolest and hottest parts of the locomotive boiler. Syphons improved water circulation in the boiler and insured more uniform temperatures in the boiler, increasing fuel efficiency.

Three-cylinder steam locomotive: A steam locomotive containing a third cylinder located under the smokebox between the two outside cylinders. It transmitted power to the driving wheels by means of a main rod which was connected to the center of a specifically designed crank axle.

Water glass: Device in the cab of a steam locomotive by which the water level in the boiler may be monitored by the engine crew. Indicates the depth that water is covering the boiler crownsheet, as it should be to prevent an explosion.

There are three basic types of steam locomotive; non-articulated (rigid frame), duplex (divides the wheels' driving force by utilizing two pairs of cylinders under a single frame), and articulated (featuring a pair of drivers under the boiler, the rear is rigidly mounted while the front pivots to negotiate curves).

The latter were the most impressive ever built. The design began when Baltimore & Ohio tested, in conjunction with Alco, the 0-6-6-0 "Old Maude" numbered 2400 in 1904.

The locomotive, a "Mallet" design, was intended for drag service on the West End. The Mallet was not an American development, the concept of Swiss engineer Anatole Mallet.

It worked by having the two cylinders nearest the cab produce high-pressure steam, which was then pumped into a pair of larger, forward cylinders to produce low-pressure steam.

The result was a locomotive which could generate high horsepower and incredible adhesion. The B&O was pleased with the results and a number of railroads went on to operate Mallets.

Over time, many (but not all) lost interest since the low gearing did not allow speeds of greater than 25 mph. In addition, the complexities of compound steam led to simple expansion variants resulting in successful late-era types like the 4-6-6-4, 2-8-8-4, and Union Pacific's 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy."

Union Pacific 4-8-4 #8444 has the "World's Fair Special" at Grand Island, Nebraska in 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-8-4 #8444 has the "World's Fair Special" at Grand Island, Nebraska in 1984. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Whyte Notation

The question is often asked, "What is meaning behind a steam locomotive's numbers and dashes?” The technical term is the "Whyte Notation," developed by Frederick Whyte, which classifies a locomotive by its wheel arrangement.

The system counts the number of lead wheels (non-powered, found at the head-end to negotiate curves), driving wheels (located directly under the boiler, providing all power and adhesion), and finally the trailing wheels (also non-powered these are located near the cab for support of the firebox and weight displacement), all of which are separated by dashes.

Perhaps the best recognized of the early types was the very successful 4-4-0, nicknamed the American, which came into widespread use during the mid-19th century.

According to Wes Barris' authoritative website, SteamLocomotive.com, there were around 25,000 manufactured from the mid-1800's through the following century. The American's Whtye Notation is broken down as follows: "4" lead wheels (two axles), "4" drivers (two axles), and "0" trailing wheels.

Steam Engines, Another Name

In a specific sense, "steam engines" describe only the devices which utilize boilers. These power plants were found in everything from ships and tractors to industrial settings and even home-heaters. However, the term has also been used to reference steam locomotives.

The train is credited with transforming the United States into an industrial powerhouse, following its introduction from England in the 1820's.

The most technologically advanced steam engines were produced from 1925, when Lima Locomotive Works introduced its so-called "Super Power" concept, through the end of, World War II.

Other noteworthy manufacturers included American Locomotive and the Baldwin Locomotive Works. Over the years steam engines became increasingly complex to achieve as much power and efficiency as possible.

In spite of this, they all operated on the same basic principal of heating water to create steam, which was then forced through pistons to generate power.

In this article we will use the term "steam engine" to denote the locomotive for clarity. While it has been retired from active service for well over a half-century, restored examples still awe the public today, from tiny 0-6-0's to Union Pacific's massive 4-8-4 #844 (the only such unit which has never been, officially, retired from active service).

The steam engine's development and its migration into railroad applications was a very slow process, occurring over a more than a century.

Much of that history is covered elsewhere in this article although another important individual in its development was inventor Oliver Evans.

According to "Railroads In The Days Of Steam," published by the editors of American Heritage, after news of Watt's design reached America (despite Britain's threat that leaking this state secret would result in a 200-pound fine and a year's imprisonment), Evans designed what he called a "steam dredge" in 1804, a combination wagon and boat.

It was known as the Orukter Amphibolos and recognized as the United States' first steam-powered vehicle. He came up with a much more practical design in 1813, a steam carriage-way to serve New York and Philadelphia.

Evans believed such a concept could whisk patrons between the two points at a brisk 15 mph.

Unfortunately, he died in 1819 before proving his theory but nevertheless held steadfast to his belief in steam-powered technology stating:

"I do verily believe that carriages propelled by steam will come into general use, and travel at the rate of 300 miles a day." His vision would eventually be proven correct.

Rio Grande 4-6-6-4 #3710 steams out of Burnham Yard in Denver; 1955. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande 4-6-6-4 #3710 steams out of Burnham Yard in Denver; 1955. Robert LeMassena photo. American-Rails.com collection.The birth of the modern steam engine is credited to Englishmen and Andrew Vivian in 1802 as previously mentioned.

Two decades later George Stephenson of Wylam, Northumberland near Newcastle upon Tyne, refined Trevithick's work.

Despite growing up poor he quickly recognized the value of education, taking it upon himself to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic.

He designed his first steam engines in 1814 and 1815. His designs not only earned distinction in Britain but also America where railroads were still under development.

The country's first, the Granite Railway, was chartered on March 4, 1826. Its purpose was to transport granite (using only horses) between Quincy and the Neponset River at Milton for the Bunker Hill Monument project.

After John Stevens showcased his self-described "Steam Waggon" in 1826 the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, envisioned by brothers Maurice and William Wurts, made a serious push to harness steam power as part of their canal operation which would transport anthracite coal from mines in the Carbondale region of Pennsylvania to New York City.

According to Jim Shaughnessy's book, "Delaware & Hudson: Bridge Line To New England And Canada," chief engineer John B. Jervis and associate, Horatio Allen visited England during the summer of 1828 and ordered four locomotives; one was contracted to Robert Stephenson & Company of Newcastle based from the same plans as the famous 0-2-2 Rocket while three others were built by Foster, Rastrick & Company of Stourbridge.

Among the later trio was the Stourbridge Lion, a little 0-4-0 that arrived in New York on May 13, 1829. Ironically, it proved the only steam engine to actually reach the D&H operation at Honesdale, Pennsylvania.

During tests carried out on August 8th that year the two men realized the locomotive, despite its superb craftsmanship, was simply too heavy for the track.

But, the trails performed that day are nevertheless recognized as the first use of a steam locomotive in the United States.

The Lion was unceremoniously scrapped in 1870 although a replica exists today. Other firsts related to the iron horse are credited to the Baltimore & Ohio and South Carolina Canal & Rail Road Company.

As the years progressed and rail demand rapidly increased, ever-larger wheel arrangements were needed. The most well-known of the 19th century was the 4-4-0 "American Type."

This steam engine saw some 25,000 built over the course of its operating life-span. It was a compact, but respectable design that could fill a range of roles, from passenger service to switching chores.

In the succeeding years ever-larger wheel arrangements were needed which featured larger boilers to produce more steam, and ultimately more power. Their extra driving wheels also achieved greater tractive effort, enabling them to pull more tonnage, especially over steep grades.

To more easily navigate curves, swiveling front trucks, or bogies, were added (such as with the 4-4-0) while trailing trucks were later needed to support larger fireboxes. By the 20th century the 2-8-2 and, to some extent, massive 2-10-2, could be found displacing the 2-8-0 in freight service.

Rio Grande 2-8-8-2 #3611 (L-132) works its way over Soldier Summit (Utah) during the 1950s. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande 2-8-8-2 #3611 (L-132) works its way over Soldier Summit (Utah) during the 1950s. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Then, the Lima Locomotive Works introduced its so-called "Super Power." In his book, "The Majesty Of Big Steam," author Brian Solomon points out that it utilized a larger firebox and a superheater; combined, these devices could sustain steam for longer periods of time, allowing the locomotive to operate more efficiently.

The first was the 2-8-4 of the 1920's followed by the 4-8-4, 2-10-4, and various articulated designs. The future in steam engine development was the "Duplex Drive," pioneered by the Baltimore & Ohio in 1937 and refined by the Pennsylvania Railroad during the 1940s.

It was a unique concept, whereby a locomotive's main set of drivers were split into two groups but still mounted under a single frame. For this reason it was considered neither an articulated nor a Mallet.

The Duplex's purpose, of course, was to achieve more power and speed by having cylinders placed on two pair of drivers instead of a single set.

Alas, despite operating a fleet of some 52 units, the PRR scrapped the technology when it became apparent the diesel was the future in motive power. Today, the revered iron horse still holds great awe, and for those examples restored, draws magnificent crowds every year.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4009 leads an eastbound at Hermosa, Wyoming on the evening of September 6, 1956. John Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" #4009 leads an eastbound at Hermosa, Wyoming on the evening of September 6, 1956. John Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.The iron horse continued to grow in an effort to meet demand. Other popular 19th century wheel arrangements included the 4-6-0 Ten-Wheeler, 2-6-0 Mogul, and 2-8-0 Consolidation. These successful designs gave way to the technologically advanced variants of the post-1900 period.

If trackside during the height of steam one was treated to fabulous scenes such as:

- Milwaukee Road's blazing fast 4-4-2's (Class A) ahead of the Hiawatha (capable of speeds in excess of 100 mph).

- Baltimore & Ohio's mammoth 2-8-8-4's (Class EM-1) working drag service over Sand Patch.

- Charming Southern Pacific 4-8-4's (Class GS) bedecked in a gorgeous two-tone orange livery while hustling the Daylights between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Alas, the cruel irony of these models was that their development coincided with the diesel's arrival. The earliest appeared during World War I to handle switching assignments. This changed during the mid-1930s Electro-Motive unveiled units for main line service.

Wheel Arrangements

American Type (4-4-0)

Atlantics (4-4-2)

Berkshires (2-8-4)

Big Boys (4-8-8-4)

Camelbacks

Cab Forwards

Challengers (4-6-6-4)

Consolidations (2-8-0)

Geared Designs

Climaxes

Heislers

Shays

Hudsons (4-6-4)

Mallets

Mikados (2-8-2)

Moguls (2-6-0)

Mountains (4-8-2)

Northerns (4-8-4)

Pacifics (4-6-2)

Prairies (2-6-2)

Santa Fes (2-10-2)

Ten-wheelers (4-6-0)

Texas Types (2-10-4)

Twelve Wheelers (4-8-0)

Yellowstones (2-8-8-4)

Famous Locomotives

Burlington 5632

Chesapeake & Ohio 614

Chesapeake & Ohio 1309

The "General"

Great Western Railway 90

Jawn Henry

Southern Pacific 4449

Spokane, Portland & Seattle 700

Texas & Pacific 610

Union Pacific 844

Union Pacific 3985

Union Pacific 4014

Manufacturers

American Locomotive Company

Baldwin Locomotive Works

Davenport Locomotive Works

H.K. Porter Company

Lima Locomotive Works

Vulcan Iron Works

Pioneering Designs

Best Friend Of Charleston

DeWitt Clinton

John Bull

Stephenson's "Planet"

Stephenson's "Rocket"

Stourbridge Lion

Tom Thumb

Mallets

2-6-6-2

2-6-6-4

Chesapeakes (2-8-8-2)

Consolidation Mallet (2-8-8-0)

Unique/Notable Designs

Southern Pacific/Overland 4-10-2

Union Pacific 4-12-2

Other Reading

Special Excursions/Events

21st Century Steam Program

American Freedom Train

Iron Horse Rambles

Chessie Steam Special

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4022 leads a westbound out of Rawlins, Wyoming on September 7, 1956. John Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 #4022 leads a westbound out of Rawlins, Wyoming on September 7, 1956. John Shaw photo. American-Rails.com collection.Examples In Service

At first they worked passenger trains when the first "E" models arrived on the B&O, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific in 1937-38. Shortly thereafter Electro-Motive successfully demonstrated their practicality, efficiency, and cost-savings in freight service following successful trails in 1939.

From this point forward the mighty iron horse was on borrowed time. Only the onset of World War II slowed the conversion and by the 1950's virtually all Class I's were fully dieselized.

Interestingly, a growing interest in the locomotive materialized after its retirement, which has only intensified into the 21st century with the restoration of powerful arrangements like Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #611, Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4014, and Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 #1309. Amazingly, even more large examples are slated for restoration.

A combination of factors can be attributed to this ranging from simple historical preservation to nostalgia. However, perhaps the greatest of all is the visual aspect. With its many moving parts synchronously working together the steam locomotive is a true sight to behold.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

New Mexico Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 23, 25 02:25 PM

The enchanting state of New Mexico, known for its vivid landscapes and rich cultural heritage, is home to a number of fascinating railroad museums. -

New Hampshire Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 23, 25 02:11 PM

New Hampshire, known for its breathtaking landscapes, historic towns, and vibrant culture, also boasts a rich railroad history that has been meticulously preserved and celebrated across various museum… -

Minnesota Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 22, 25 12:17 PM

The state of Minnesota has always played an important role with the railroad industry, from major cities to agriculture. Today, several museums can be found throughout the state.