Parlor Car (Train): Development, History, Photos

Published: January 31, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Railroads have played an instrumental role in shaping the landscape and society of the United States. From the first steam locomotives of the early 19th century to the high-speed trains of today, rail transport has evolved to meet the diverse needs of passengers and freight alike.

Among these developments, the parlor car stands out not only as a testament to advances in passenger comfort and luxury but also as a reflection of the cultural and economic epochs it journeyed through.

This article explores the rich history and purpose of the parlor car on U.S. railroads, tracing its evolution and significance from its inception to its decline.

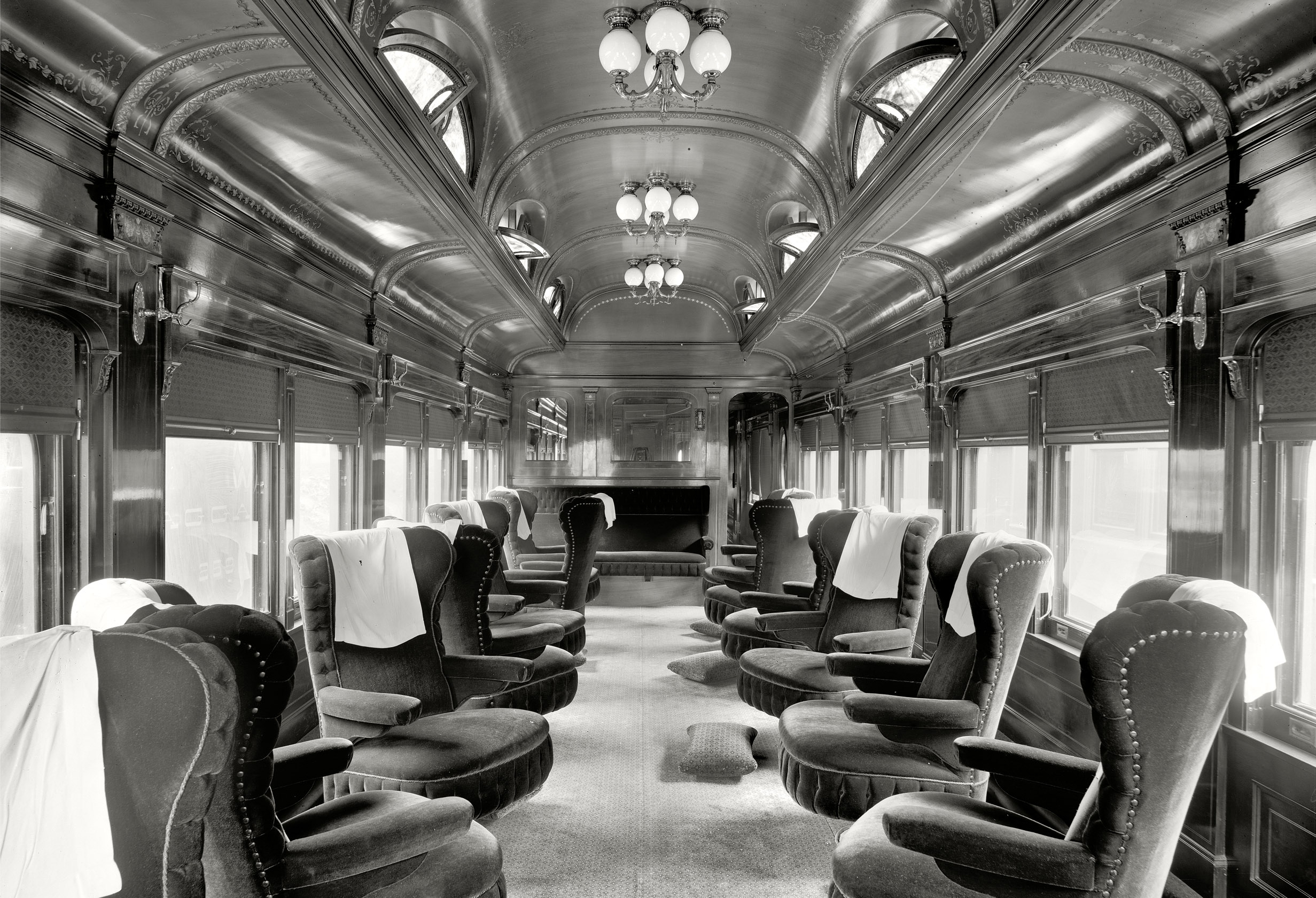

An interior view of Pere Marquette parlor car #25 from 1905, depicting the common celestory roofs, plush seating, and ornate Victorian decoration of the period.

An interior view of Pere Marquette parlor car #25 from 1905, depicting the common celestory roofs, plush seating, and ornate Victorian decoration of the period.Development

The concept of the parlor emerged during an era when railroads were synonymous with innovation and modernization. It was introduced in the mid-19th century as part of a wave of upgrades that took passenger rail travel from a basic mode of transportation to an experience of elegance and comfort.

The earliest parlors to operate were put into service on the Great Western Railway of England in 1838 according to the book, "The Railroad Passenger Car" by author August Mencken.

Although the service was not a prominent feature on trains prior to 1860s across the Northeastern and Great Lakes regions, many instances can be identified. The first in the U.S. appeared on the Erie Railroad in 1843.

The so-called "Diamond cars" - due to the shape of their windows - featured upholstered seats that could be converted into coaches. However, they proved too heavy and were soon discontinued.

In 1845, the Eastern Railroad acquired several luxury cars equipped with “each seat being a separate armchair, designed to pivot.” Clearly, this reflects parlor car-style seating, yet the capacity of each car to house 70 individuals suggests that they might not have been intended purely as such.

According to the book, "The American Railroad Passenger Car" by author John H. White, Jr., in September, 1867 the Wagner Palace Car Company outshopped the first parlor cars from a manufacturer.

Accommodations

A parlor car offered what no other train car at the time could: an opulent retreat where affluent passengers could relax in luxury, isolated from the less refined accommodations found in standard passenger cars.

At its core, the parlor was a first-class passenger coach tailored for day travel. One of the first companies to embrace this concept was the Pullman Company.

Passengers enjoyed amenities such as wide windows for panoramic views, high-backed seats, carpeting, and sometimes even chandeliers. As railroads spread across the U.S., parlors became symbols of sophistication and the preferred choice for business executives, politicians, and other elites.

Use

Parlors were not a feature on every train or even on every railroad, remaining a relatively scarce category of car even compared to sleepers or dining cars. They scarcely surpassed 2.5% of the total passenger car fleet.

Most were in operation within what is now termed the Northeast corridor, linking major terminals in cities such as Boston, New Haven, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. Smaller parlor operations connected proximate urban centers like Chicago-Milwaukee or San Francisco-Los Angeles.

They also connected state capitals with major satellites, such as Chicago-Springfield or Albany-New York City, to facilitate the travel of politicians and lobbyists. Wealthy resort areas could sustain parlor services, at least seasonally, with routes such as Florida’s Jacksonville-Miami-Key West and New England’s Boston-Bar Harbor serving as examples. Thus, virtually all parlor car operations were characterized by short runs, typically not exceeding 300 miles, between major cities.

Purpose and Functionality

The primary purpose of the parlor was to meet the demand for premium travel experiences at a time when economic growth was creating a new class of wealthy travelers.

Beyond mere transport, these cars served as mobile lounges and meeting spaces, offering privacy and exclusivity that other modes of travel could not match. In addition to providing comfort, parlor cars conveyed status; riding in one was a clear indication of social standing.

Enhancing the appeal of parlor cars were the services provided onboard. Attentive porters, known for their exceptional personal service, catered to passengers' needs, often going beyond what one would expect in a public transport setting.

Refreshments were available, and some parlors even offered light meals, further adding to the sense of luxury. These amenities enabled passengers to conduct business, entertain guests, or simply enjoy a relaxing voyage.

Challenges and Decline

Despite their earlier popularity, parlors faced significant challenges as the 20th century progressed. The rise of the automobile and the development of the interstate highway system in the post-World War II era began to lure passengers away from trains. Cars offered more flexible travel options, and as ownership became widespread, the once-lucrative parlor car market began to dwindle.

In tandem, the emergence of commercial aviation offered another formidable competitor. Airlines provided faster travel options across longer distances, rendering the time luxury by rail less appealing. Parlor cars, designed for daylight travel and short to medium distances, found themselves at odds with changing passenger preferences and evolving transportation infrastructure.

By the 1960s, many railroads had discontinued parlor car services, or taken over these directly from Pullman which for decades had operated them under contract, due to declining demand and financial unsustainability.

The shift was further exacerbated by the general decline in passenger rail service in the U.S., as freight transport took precedence and trains were seen as outdated compared to the speed and effectiveness of air travel.

Legacy and Modern-Day Relevance

Today, the parlor is largely a relic of the past, yet its influence is still felt in various forms of transportation that prioritize luxury and experience.

Modern first-class airplane cabins, luxury bus services, and even some train services still echo the ethos of the parlor car—comfort, exclusivity, and a premium passenger experience.

Heritage railroads and tourist excursion trains have helped preserve the legacy of parlor cars by showcasing restored versions to nostalgic travelers and historians alike.

These functioning rail museums offer a glimpse into the grandeur of yesteryear and serve as reminders of an era when the journey was as pleasurable as the destination.

The history of the parlor encapsulates the broader story of the American railroad: a tale of innovation, adaptation, and eventual decline in the face of shifting technological and societal landscapes.

While parlor cars no longer traverse the railroads in their original capacity, their legacy endures in the annals of transportation history, illustrating the ever-evolving quest for comfort and distinction while traveling.

Recent Articles

-

Oregon Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 03:11 PM

With its rich tapestry of scenic landscapes and profound historical significance, Oregon possesses several railroad museums that offer insights into the state’s transportation heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 02:56 PM

Today, several museums in North Caorlina preserve its illustrious past, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of railroads with artifacts, model trains, and historic locomotives. -

New Jersey Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 11:48 AM

New Jersey offers a fascinating glimpse into its railroad legacy through its well-preserved museums found throughout the state.