O. Winston Link: Pioneering Railroad Photographer

Published: July 24, 2024

By: Adam Burns

O. Winston Link, born on December 16, 1914, in Brooklyn, New York, is celebrated for his extraordinary contributions to railroad photography.

Over his lifetime, Link became a pioneering figure, whose compelling black and white photographs capture a period of American history with unparalleled detail and evocative power.

His work most often centered on the Norfolk and Western Railway and its late steam era operations in the latter 1950s. This powerful and capivating pieces continue to inspire and awe even into the modern era.

He is widely considered the master of the juxtaposition of steam railroading and rural culture. Today, much of his work can be seen at the official O. Winston Link museum in Roanoke, Virginia.

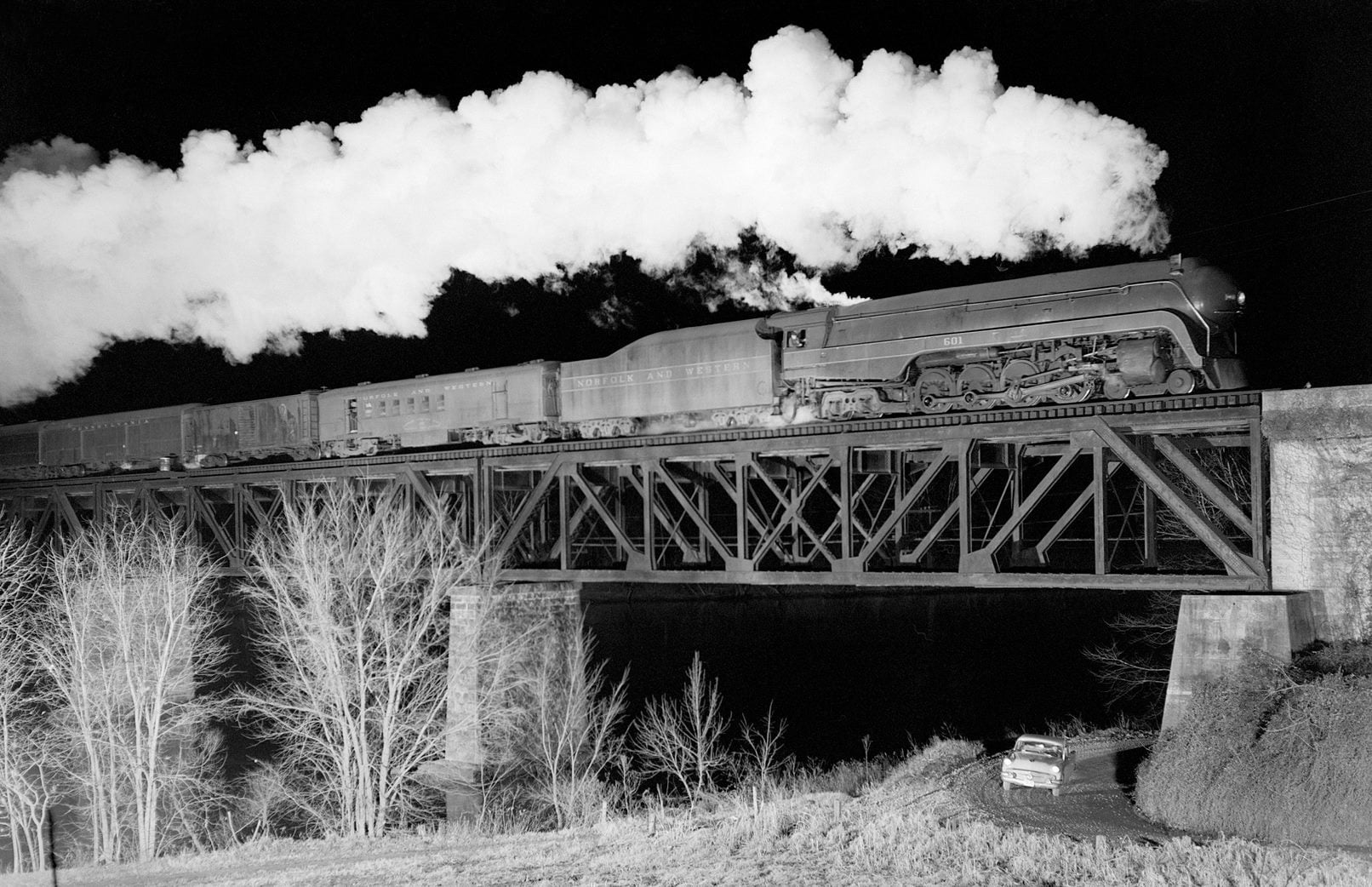

Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #601 steams across Bridge 201 above the New River at Radford, Virginia with Train #17, the first section of Southern's southbound "Birmingham Special," on the night of December 17, 1957. O Winston Link photo.

Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #601 steams across Bridge 201 above the New River at Radford, Virginia with Train #17, the first section of Southern's southbound "Birmingham Special," on the night of December 17, 1957. O Winston Link photo.Early Life and Influences

Link demonstrated an early interest in technology and photography. As a child, he was fascinated by cameras and often experimented with them. This nascent interest would evolve into a lifelong passion.

After completing his studies at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, he began his career as a photographer and engineer, initially working with public relations and industrial photography.

The Intersection of Railroads and Photography

O. Winston Link's most iconic work came during a period of transition for the American railroad industry. In the early 1950s, steam locomotives, which had dominated the railways for over a century, were rapidly being replaced by diesels.

Recognizing this shift, Link saw an opportunity to document the dwindling era of steam railroads, focusing his efforts on the Norfolk and Western Railway, the last major U.S. freight railroad to operate steam locomotives.

The N&W was heavily invested in the movement of high grade bituminuous coal found predominantely in southern West Viriginia. As a result, the company continued to maintain a highly efficient fleet of steam locomotives well into the late 1950s.

In fact, it has been said the railroad's maintenance and development of these late era iron horses rivaled the best designs from the three major steam builders.

The Project of a Lifetime

Link’s project to capture the steam-powered railroads began in 1955 and continued until 1960. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Link chose to shoot his subjects exclusively at night.

This decision was driven by both artistic vision and technical considerations. Nighttime allowed him to control lighting conditions to an exceptional degree, creating dramatic contrasts and ensuring that the trains themselves stood out against the surrounding landscape.

To achieve this, Link used an extensive and sophisticated setup of flashbulbs and synchronized lighting. His lighting orchestrations were elaborate; often involving more than 40 flashbulbs triggered simultaneously. This meticulous planning transformed mundane scenes into arresting compositions that highlighted the sheer power and beauty of the locomotives.

A 1952 Buick "Super" gets some petrol from a classic gravity gas pump at Vesuvius, Virginia as one of the Norfolk & Western's streamlined Class K-2a 4-8-2's, #131, speeds past along the Shenandoah Division with northbound Train #2 in 1956. O. Winston Link photo.

A 1952 Buick "Super" gets some petrol from a classic gravity gas pump at Vesuvius, Virginia as one of the Norfolk & Western's streamlined Class K-2a 4-8-2's, #131, speeds past along the Shenandoah Division with northbound Train #2 in 1956. O. Winston Link photo.Technical Mastery and Innovations

Link’s technical prowess was a cornerstone of his work. He was not merely taking photographs but creating them. This approach established him as a master of photographic technique. His understanding of light, timing, and exposure enabled him to construct scenes that appeared almost surreal.

One of his most renowned photographs, "Hot Shot Eastbound," epitomizes his approach. Taken on August 2, 1956, in Iaeger, West Virginia, the image features a N&W steam train passing by a drive-in movie theater, where a screen displays a romantic scene.

The juxtaposition of modern American life with the power of industrialization captures a moment frozen in time, resonant with nostalgia and a sense of impending change.

The Human Element

A distinctive feature of Link’s work is the inclusion of human subjects within his railroad scenes. This choice was intentional and reflective of his belief that the story of the railway was also a story about the people who lived in its proximity.

Whether it was farmers working late into the night, children playing near the tracks, or workers maintaining the locomotives, Link’s photographs conveyed a deep narrative that connected the railroads to the broader tapestry of American life.

Publications and Exhibitions

Despite the artistic and technical brilliance of his work, O. Winston Link’s photographs did not immediately receive widespread recognition.

It was not until the publication of his book, "Steam, Steel & Stars: America's Last Steam Railroad" in 1987, that his work gained the acclaim it deserved. The book featured many of his iconic images and brought attention to the high degree of craftsmanship involved in their creation.

Following the release of his book, Link’s photographs were exhibited in numerous galleries and museums, including the George Eastman Museum and the Smithsonian Institution. These exhibitions introduced a broader audience to the timeless quality of his images and secured his legacy as a pioneer in railroad photography.

In Film

Link would make a brief appearance in a major motion picture when he was briefly featured as the engineer on a coal train in "October Sky." The locomotive used in the scene was Southern Railway 2-8-2 #4501.

Legacy and Influence

O. Winston Link passed away on January 30, 2001, leaving behind a remarkable body of work that chronicled the end of an era. His photographs serve as a historical record and have influenced countless photographers since.

Link’s use of lighting, composition, and his ability to capture dynamic narratives within still images continue to inspire and inform photographic practices today. His dedication to his craft, willingness to experiment, and meticulous attention to detail set a standard for artistic and technical excellence.

In the years following his death, interest in Link’s work has only grown. His photographs are often referenced in discussions of 20th-century American photography and industrial history.

The O. Winston Link Museum, located in the restored N&W Railway passenger station in Roanoke, Virginia, serves as a dedicated space to celebrate and preserve his contributions.

Conclusion

The life and work of O. Winston Link underscore the power of photography as a medium to capture and convey transitional moments in history.

His meticulous documentation of America’s last steam railroads is a testament to his artistic vision and technical expertise.

Through his photographs, Link immortalized not just the machines but the human spirit intertwined with them, leaving an indelible mark on the canon of American photography.

Recent Articles

-

Oregon Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 03:11 PM

With its rich tapestry of scenic landscapes and profound historical significance, Oregon possesses several railroad museums that offer insights into the state’s transportation heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 02:56 PM

Today, several museums in North Caorlina preserve its illustrious past, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of railroads with artifacts, model trains, and historic locomotives. -

New Jersey Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 11:48 AM

New Jersey offers a fascinating glimpse into its railroad legacy through its well-preserved museums found throughout the state.