Grand Trunk Railway: Map, History, Timetables

Published: February 14, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The story of the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) is, in many ways, the narrative of Canada's maturation as a nation. This railway was not just a mere transportation network; it was the lifeblood that carried the economic fervor and national aspirations of a young Canada across vast expanses of territory.

At its peak the GTR maintained a network stretching across the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario, as well as the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Its administrative operations were centered in Montreal, Quebec, while its corporate headquarters were situated in London. It laid the groundwork, together with the Canadian Government Railways, for what ultimately evolved into today's Canadian National Railway.

The GTR's initial charter authorized the construction of a line primarily following the northern bank of the St. Lawrence River, connecting Montreal to Toronto. Subsequently, it was expanded to include routes extending eastward to Portland, Maine, and westward to Sarnia, Ontario. Over the years, the Grand Trunk Railway incorporated numerous subsidiary lines and branches, notably:

1. Grand Trunk Eastern, which served regions in Quebec, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

2. Central Vermont Railway, which operated in Quebec, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

3. Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, which spanned Northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

4. Grand Trunk Western Railroad, which facilitated transit in Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois.

Had the system not faltered it likely would have eclipsed either Canadian National and/or Canadian Pacific as Canada's largest railroad.

System Map (1893)

Early Development

In the mid-19th century, Canada and its American neighbors were on the cusp of rapid industrial growth. The nascent territories required robust transportation systems to connect resources, industries, and people.

The idea for the Grand Trunk Railway emerged in this context, spearheaded by British financiers seeking to create a transcontinental railway network in North America that would bolster trade and solidify political ties between Canada and Britain.

Founded on November 10, 1852, the Grand Trunk Railway initially aimed to bridge the key economic centers along the St. Lawrence River, linking Montreal and Toronto. The railroad's construction not only promised improved trade routes but also served as a tool for unifying disparate Canadian provinces and fortifying national defense against the expanding United States.

The company's charter was soon expanded to include a route extending eastward to Portland, Maine, and westward to Sarnia, in what was then known as Canada West. The railroad was not built entirely via new construction as several subsidaries comprised its eastern network.

In 1853, the GTR acquired the St. Lawrence & Atlantic Railroad, which operated from Montreal to the border of Canada East and Vermont, along with its parent company, the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad, which provided access to the port facilities in Portland.

By 1855, a line to Lévis was constructed via Richmond from Montreal, forming part of the much-discussed "Maritime connection" for British North America. Additionally, in 1855, the GTR acquired the Toronto & Guelph Railroad, changing its initial route to reach Sarnia, which subsequently became a key transfer point for Chicago-bound freight.

GTR's line from Montreal to Toronto began operations in October 1856, while the segment from Toronto to Sarnia was completed in November 1859. That same year, a ferry service was established across the St. Clair River to Fort Gratiot (present-day Port Huron, Michigan).

Engineering Feats and Expansion

The Grand Trunk played a pivotal role in driving the Canadian Confederation. The existing colonial economy, which was organized around the water-based trade route from the Maritimes through the St. Lawrence River and the lower Great Lakes, experienced significant expansion due to the establishment of this rail counterpart.

The booming trade activities of the 1850s within the United Province of Canada, and the ensuing demand for connection to the Maritimes via rail, necessitated the integration of the entire geopolitical region. Consequently, the GTR extended its tracks from Lévis to Rivière-du-Loup.

By 1867, the GTR had emerged as the world's largest railway network, amassing over 1,277 miles of track that linked its ocean port at Portland, Maine; its river port at Rivière-du-Loup; the three northern New England states; and significant portions of the southern regions of the new provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

By 1880, the railroad had expanded from Portland in the east to Chicago, Illinois, in the west, incorporating the Grand Trunk Western Railroad between Port Huron and Chicago. Interestingly, the GTW long outlived its parent, remaining a CN subsidiary, including its own livery, until the end of 1991.

The GTR is associated with several notable engineering achievements, including the first successful bridging of the St. Lawrence River, marked by the opening of the inaugural Victoria Bridge in Montreal on August 25, 1860 (subsequently replaced by the current structure in 1898); the bridge over the Niagara River connecting Fort Erie, Ontario, with Buffalo, New York; and the construction of a tunnel beneath the St. Clair River, linking Sarnia, Ontario, and Port Huron, Michigan. This tunnel, which opened in August 1890, replaced the existing railcar ferry service at that location.

Economic Impact

Navigating through the burgeoning industrial age, the GTR played a pivotal role in the economic development of Canada. It stimulated job creation, from the construction phases to daily operations, and fostered secondary industries such as steel production and manufacturing.

Moreover, the GTR revolutionized Canada's agricultural landscape. Farmers now had access to distant markets, enhancing economic stability and prosperity. Goods could be transported with unprecedented speed and efficiency, opening up opportunities for exporting Canadian products globally. This was particularly true for Quebec and Ontario, where the railway promoted urbanization and even helped smaller towns to grow and flourish due to improved market accessibility.

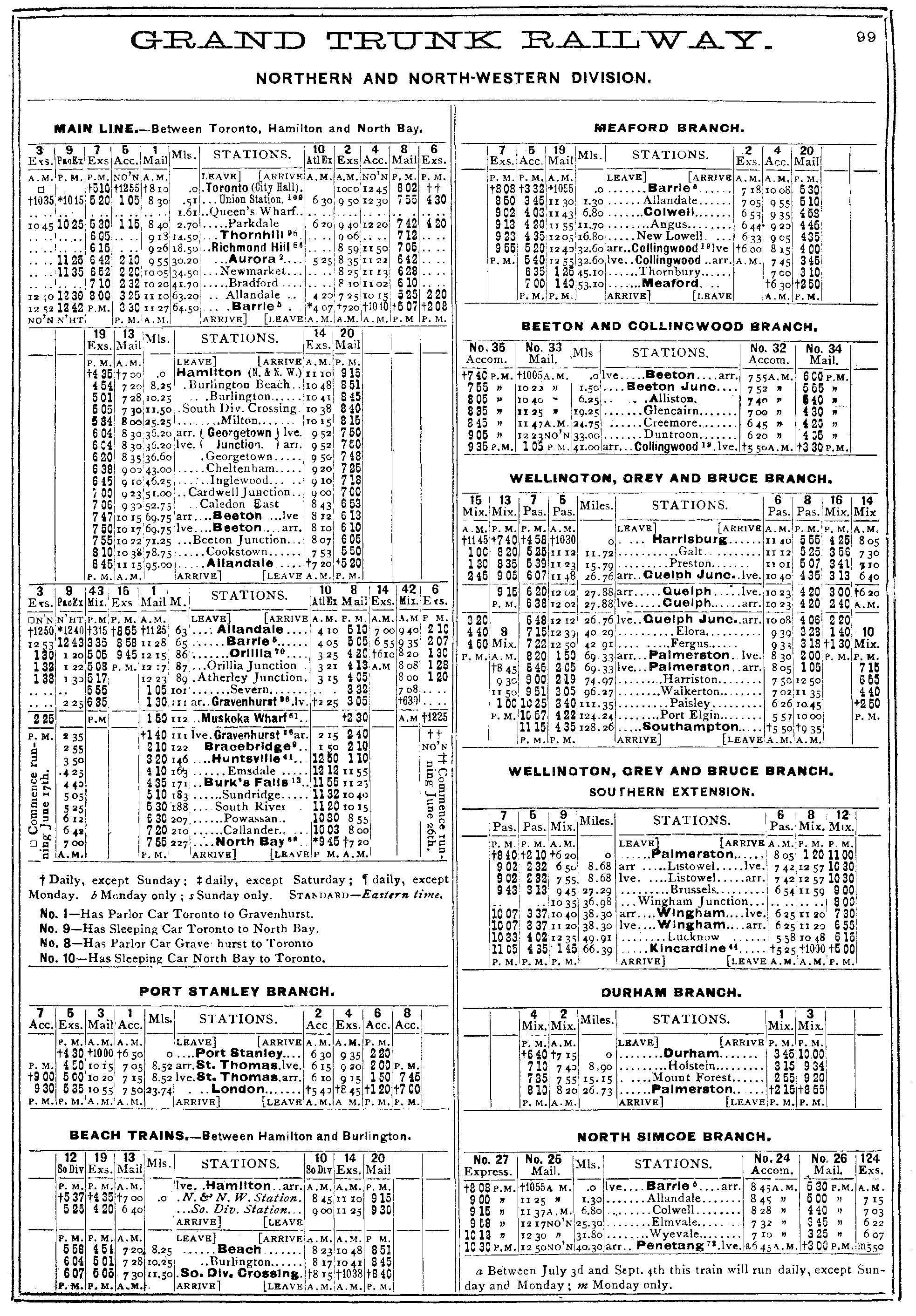

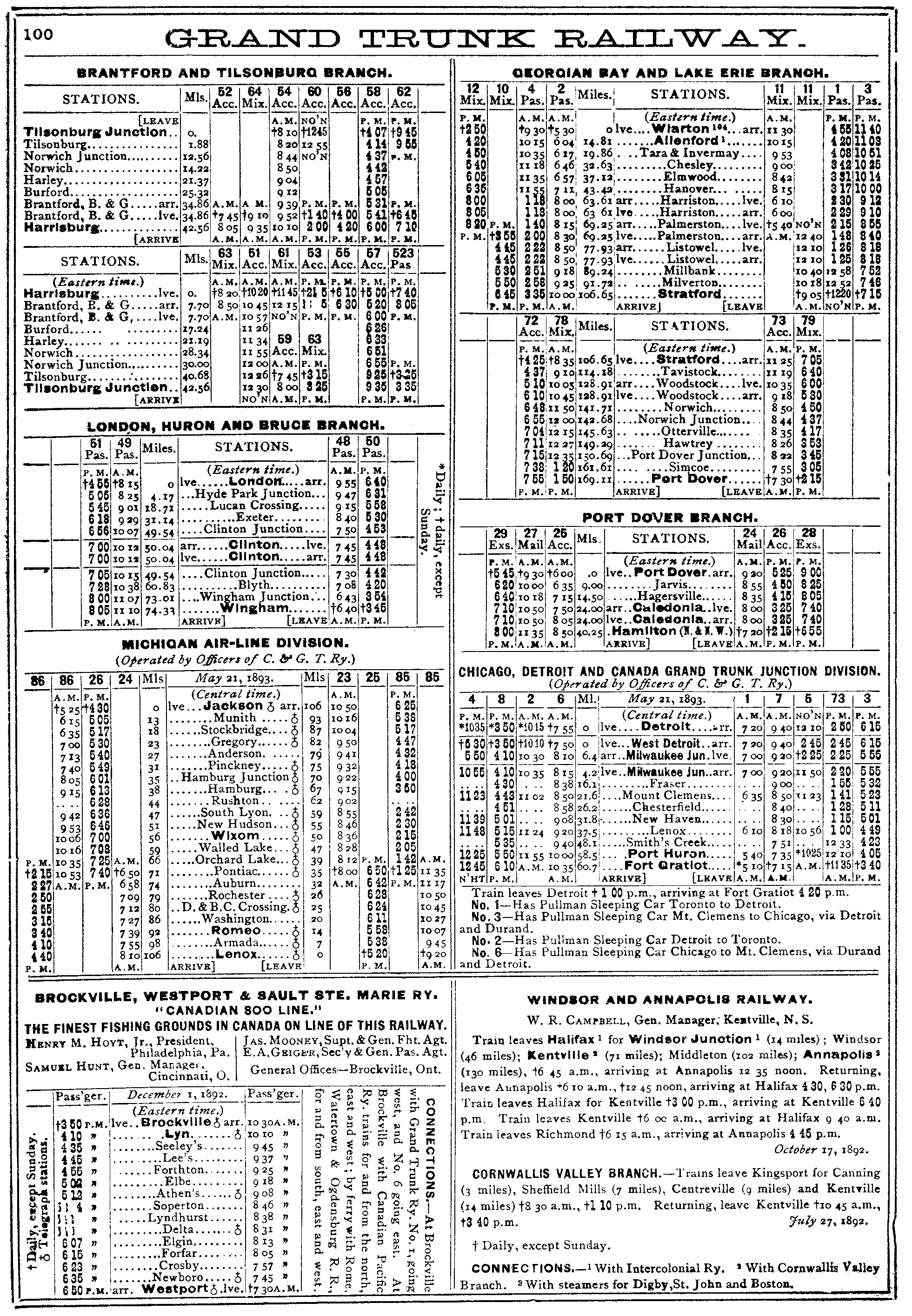

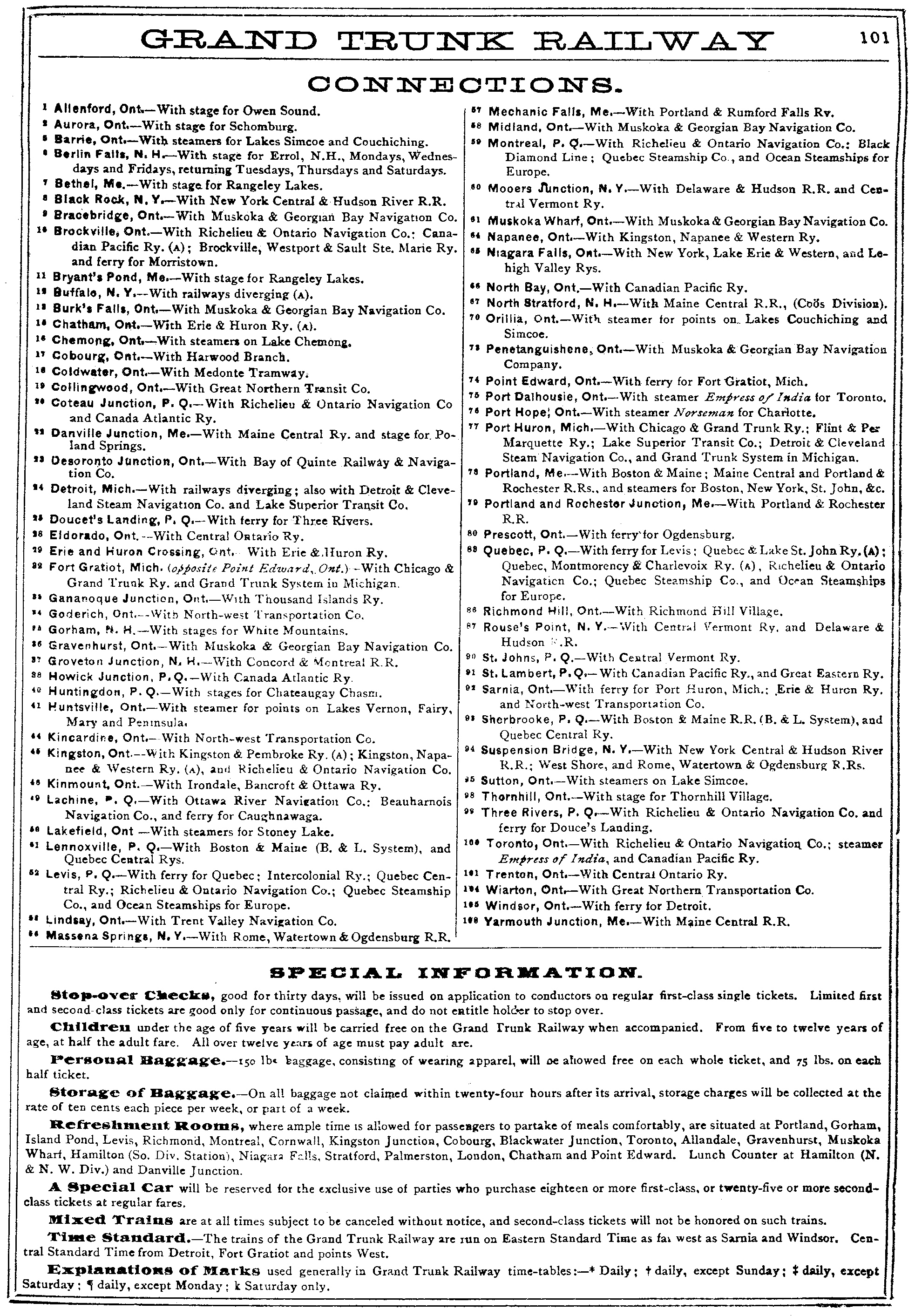

Timetables (1893)

Challenges and Competition

Despite its successes, the GTR was not without challenges. Financial difficulties emerged as a recurring theme throughout its history. The costs of construction and maintenance were astronomical, and the initial revenues often fell short of expectations. The financial misadventures reached a critical point in the late 1800s, forcing the railway to rely heavily on British funding.

Competition also posed a significant threat to the company. With the rise of Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) and other regional lines, the race to control Canadian and cross-border transportation intensified. CP had a competitive edge, offering a more direct transcontinental route completed in 1885, which exacerbated the GTR's struggles to maintain profitability.

Moreover, the rise of motor vehicles and road transport in the early 20th century introduced new challenges, gradually eroding the monopoly of the railways.

Political Influences and National Unification

The political implications of the Grand Trunk were no less significant than its economic impact. The creation of a rail network complemented the aspirations of British colonial policy-makers who wished to strengthen ties with Canada. The railroad became a conduit for people and ideas, embodying a means of cultural exchange between different regions of the young Dominion.

Westward Expansion

As the preeminent railway system in British North America, the GTR was reportedly solicited by the federal government shortly after Confederation to explore the possibility of constructing a rail line extending to the Pacific coast in British Columbia. However, GTR declined this proposal, compelling the government to legislate the formation of the Canadian Pacific to satisfy British Columbia's prerequisites for joining Confederation.

Witnessing CP's near-monopoly on rail services and the burgeoning influx of immigrants westward from Ontario, GTR later reversed course and intended to build westward.

The federal government prompted the railroad to collaborate with the Canadian Northern (CN), a then-regional system operating in the Prairies, yet no agreement materialized. Consequently, CN embarked on developing its own transcontinental network, which led GTR, in 1903, to forge an arrangement with the government of Wilfrid Laurier to establish a third rail system spanning from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Under this agreement, GTR would construct (with federal assistance) and operate the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTPR) from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Concurrently, the government would construct and own the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR), running from Winnipeg to Moncton, New Brunswick, via Quebec City, which GTR would also manage.

As part of this strategy, the federal government encouraged GTR to acquire the Canada Atlantic Railway (CAR), which had lines stretching southeast from Ottawa to Vermont and west from Ottawa to Georgian Bay. The Grand Trunk effectively assumed control of CAR in 1905, although its acquisition was not officially sanctioned by Parliament until 1914.

The geographical routing of these systems was highly speculative, as the GTPR’s main line was positioned further north than CP's in the Prairies, with the NTR even farther north of major population centers in Ontario and Quebec.

Decline

Despite having the most advantageous crossing of the Continental Divide in North America at Yellowhead Pass, construction costs on GTPR skyrocketed. GTR's frugally-minded president, Charles Melville Hays, perished aboard the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912.

His untimely death is believed to have contributed to inadequate management at the railroad over the following decade, affecting their decision to abandon the incomplete Southern New England Railway to Providence, Rhode Island, initiated in 1910.

The construction of the GTPR/NTR commenced in 1905, with GTPR opening to traffic in 1914, followed by the NTR in 1915; however, the ill-fated Quebec Bridge along the NTR remained incomplete for several more years.

The earliest signs of the arrangement's deterioration appeared when GTR refused to operate the NTR, citing economic constraints. Faced with the overwhelming costs of constructing the GTPR and the limited financial returns, GTR defaulted on its loan obligations to the federal government in 1919.

Consequently, GTPR was nationalized on March 7 of that year, managed by a federal Board of Management until it was transferred under the jurisdiction of the Canadian National on July 20, 1920.

GTR encountered severe financial struggles due to the GTPR, with its shareholders, mostly based in the United Kingdom, determined to avert the company's nationalization.

Ultimately, on July 12, 1920, the railroad was placed under the oversight of another federal Board of Management, prolonging legal disputes until the Grand Trunk was fully integrated into the CN on January 20, 1923, coinciding with the merger of all constituent companies into the Crown corporation.

At the time of CN's acquisition, the Grand Trunk's system comprised approximately 125 smaller companies, spanning 8,000 miles within Canada and 1,164 miles in the United States.

Continuing Influence and Modern Relevance

The legacy of the GTR is palpable even today. Canadian National Railways remains a crucial transport player within Canada and beyond. The architectural heritage of the GTR, with historic bridges and ornate railway stations, remains a testament to the industrial audacity of their builders.

Many of the original GTR routes are still used, forming the backbone of a national transportation infrastructure that continues to be essential for trade and commerce. Moreover, the visionary amalgamation of territories that the GTR encouraged continues to influence Canadian socio-political life, highlighting the importance of physical networks in shaping national consciousness.

Legacy

The Grand Trunk Railway was more than just a series of tracks and trains; it was an ambitious undertaking that transformed a country's landscape, both literally and metaphorically.

With profound effects on Canada's economy, society, and international standing, the GTR stands as a monument to the dynamic ingenuity and indomitable spirit of an era.

The legacy of the Grand Trunk Railway continues to inform future transportation strategies, illustrating the enduring significance of connecting communities across geographical and cultural divides.

Recent Articles

-

Oregon Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 03:11 PM

With its rich tapestry of scenic landscapes and profound historical significance, Oregon possesses several railroad museums that offer insights into the state’s transportation heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 02:56 PM

Today, several museums in North Caorlina preserve its illustrious past, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of railroads with artifacts, model trains, and historic locomotives. -

New Jersey Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 11:48 AM

New Jersey offers a fascinating glimpse into its railroad legacy through its well-preserved museums found throughout the state.