Coal & Coke Railway: Serving The Heart Of WV

Published: February 11, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Coal and Coke Railway (C&C) was a significant component of West Virginia's burgeoning coal industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Chartered in 1902, the railway emerged as a critical transportation link for the coalfields located in the region, facilitating the movement of coal and coke—a fuel derived from heating coal in the absence of air—to markets across the United States.

The railway was a brainchild of entrepreneur Henry Gassaway Davis, a prominent industrialist and politician, who envisioned creating a more efficient route to transport the mineral wealth of central West Virginia.

The C&C began as the Charleston, Clendenin & Sutton Railroad, established in 1891, underwent a reorganization in 1906 to become the Coal & Coke Railway. In 1916, it was leased by the Baltimore & Ohio, which eventually fully integrated it in 1934, designating the route from Charleston to Elkins as the Charleston Division.

Various factors, such as the depletion of large-scale timber resources, a gradual downturn in the central West Virginia coal industry, and the shutdown of a refinery at Falling Rock, prompted the B&O to discontinue services on the Charleston Division at various intervals since 1941. During the 1940s, the railroad began sharing trackage rights with the Western Maryland Railway closer to Elkins and abandoned its mainline segment between Adrian and Midvale.

By 1972, the company ceased operations on the portion of its former mainline between Midvale and Roaring Creek Junction due to multiple mine closures. Subsequent attempts by the B&O to abandon much of the line south of Gassaway were partially averted by interventions from Conrail and the Elk River Railroad.

However, the final closure of a mine on the revitalized Buffalo Creek Railroad led to the remaining tracks south of Burnsville being repurposed chiefly for railcar storage and refurbishment at Gassaway, which ended in 2022.

Presently, significant segments of the former Coal & Coke Railway extending from Gassaway to Charleston are in the process of transformation into a linear state park intended for recreational activities.

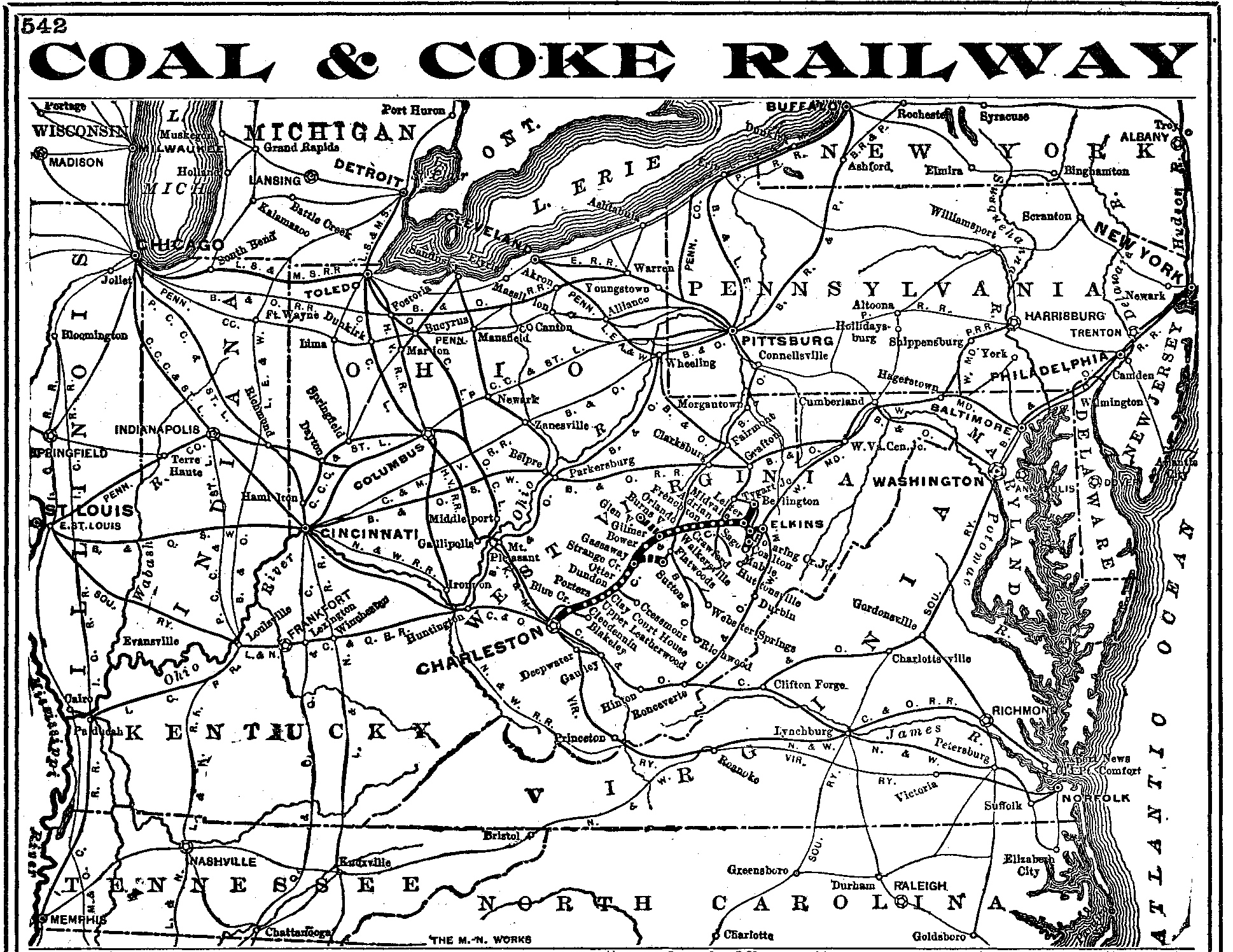

System Map (1910)

The Coal & Coke Railway (C&C) was inaugurated on May 14, 1902, by former Senator Henry Gassaway Davis. Its primary intent was to establish a link between the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad and the Kanawha & Michigan Railway in Charleston with the WVC&P near Elkins. Senator Davis had acquired substantial tracts of land in Randolph County's Roaring Creek area and neighboring counties, known for their abundant coal and virgin timber resources. The C&C was capitalized at $5 million.

In a strategic move to enable the construction of the C&C, Davis sold the WVC&P to distinguished railroad magnate George L. Gould in January 1902. Following this, Davis purchased the RC&C and RC&B. Gould, who had influence over the Wabash and aspired to establish a railway to Pittsburgh from the WVC&P's reach, had also procured the Western Maryland Railroad (WM), extending to Hagerstown, with plans for further expansion to Cumberland. Subsequently, the WVC&P was integrated into the WM.

Construction of the C&C commenced on April 17, with active progress on Tunnel No. 1 (Kingsville Tunnel) by May. By late November, significant advancements had been achieved on Tunnel No. 3, Tunnel No. 4 (Shipmans Gap Tunnel), and Tunnel No. 5 (Reeds Tunnel).

In late October, Senator Davis considered acquiring the CC&C. However, he found it in disrepair, characterized by numerous wooden trestles, irregular track conditions, and a lack of ballast. Despite these hurdles, Davis completed the acquisition on November 19.

The substantial 2,400-foot Tunnel No. 1 (Kingsville Tunnel) was finalized in mid-January 1903, and work on Tunnel No. 2 had started. By February, track was laid from Leiter to Loop, and on July 20, a contract was assigned for the construction of Tunnel No. 12 (Little Otter Tunnel) between Perkins Fork and Brushy Fork of Little Otter Creek. By January 1904, tracks extended to Tunnel No. 3, with Tunnel No. 5 (Reeds Tunnel) nearly completed, and construction of Tunnel No. 6 (Sago Tunnel) beginning in February. On March 10, bids were solicited for a 35-mile construction segment between Frenchton and Copen Run.

After overcoming challenges in securing the right-of-way, as the Little Kanawha Railroad had prior claims, Davis successfully acquired the railway on August 24. This acquisition was advantageous, offering a favorable alignment and reduced gradients from Copen Run to Burnsville and Walkersville. Tunnel No. 8 (Jones Tunnel) was completed by August, and train operations between Elkins and Sago commenced on September 19. The C&C's largest stone bridge, consisting of two 52-segment arches over French Creek, was completed on January 10, 1905. Tunnel No. 12 (Little Otter Tunnel) was finished on August 15, albeit behind schedule by one year. By November 17, only five miles of track were pending, culminating in the completion of the C&C on December 1 when the final spike was driven at Walkersville, marking the conclusion of the 175.6-mile stretch from Charleston to Elkins.

Upon completion, the C&C featured 12 tunnels and 30 steel bridges from Norton to Gassaway and was notably devoid of wooden trestles or timber bridges. The Coal & Iron Railroad, an extension of the C&C, was completed earlier in 1903, extending from Elkins to Durbin near the headwaters of the Greenbrier River, where it interconnected with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Greenbrier Division.

Given the topographic challenges, the construction was an engineering marvel of its time, involving numerous cuts through mountainous terrain, bridges over deep valleys, and tunnels through solid rock.

The railway spurred economic development in West Virginia's counties by providing jobs and increasing the demand for coal production, thereby attracting both skilled and unskilled labor from across the country. It facilitated the growth of several towns along its route, contributing to the socio-economic transformation of the region.

Despite its early success, the Coal and Coke Railway, like many railroads of its era, faced financial difficulties due to fluctuating coal prices and growing competition from alternative energy sources and transportation methods. By the mid-20th century, the decline in demand led to its eventual absorption by larger rail networks. Today, while the Coal and Coke Railway no longer operates, its legacy endures, marking an era of economic ambition and industrial growth in West Virginia’s history.

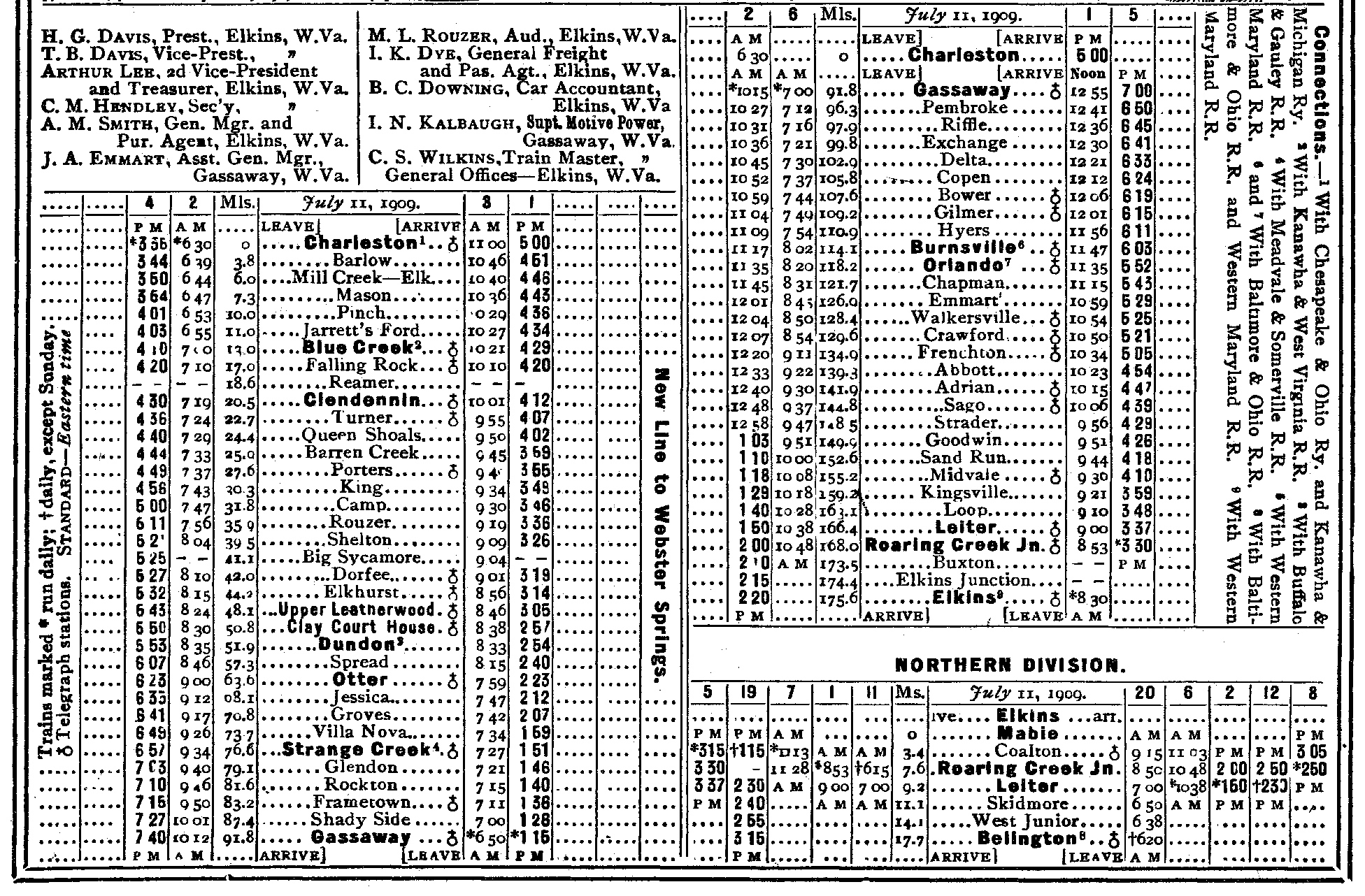

Timetable (1910)

B&O Operations

The C&C successfully tapped into the rich natural resources of the state's central region, as projected. Their ventures involved acquiring and managing the Davis Colliery Company's land, which occupied around 20,000 acres in the Roaring Creek vicinity. This operation included five physical sites producing 3,500 tons of coal and 700 tons of coke daily. A significant development occurred in Clay County when Joseph G. Bradley, inheriting 102,000 acres of untouched timber, founded the Elk River Coal & Lumber Company in 1903. Bradley's inheritance came from his father, Simon Cameron, a Pennsylvania politician who had served as Secretary of War under Abraham Lincoln. In 1904, Bradley incorporated the Buffalo Creek & Gauley Railroad (BC&G), intended to extend 104 miles from Dundon on the C&C eastward to Huttonsville in Randolph County, though only 18.5 miles reached his company town of Widen.

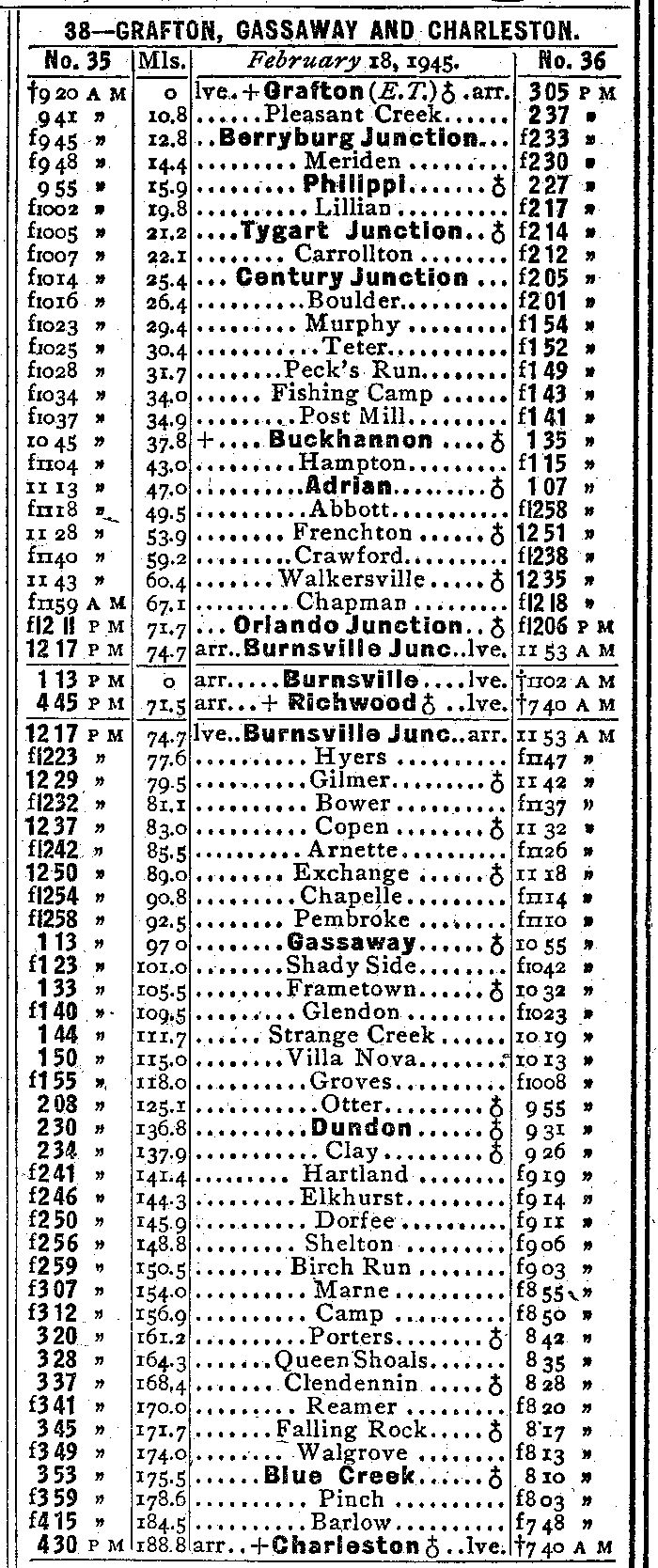

On November 23, 1912, Mr. Davis retired from his role at the C&C at the age of 89. He passed away in 1916, concluding his leadership. At the time of his death, the C&C spanned 175.6 miles, with a notable 16-mile stretch connecting Belington to Norton, Mabie, and Coalton, and a 6.5-mile branch from Gassaway to Sutton. The network also linked with the B&O at Belington, the WM at Roaring Creek Junction and Elkins, the Kanawha & Michigan at Charleston, and featured switching agreements with the Chesapeake & Ohio in Charleston. In 1917, the B&O leased the C&C, which then operated as the Coal & Coke Branch of the B&O, granting the B&O a direct Charleston link, 188.5 miles from Grafton.

On August 14, 1940, trackage rights between Elkins and Belington were permitted for sharing between the B&O and WM. Consequently, the B&O ceased operations between RC&B at Leiter near Roaring Creek Junction and Belington, with the WM abandoning the segment from Roaring Creek Junction to Elkins. In 1941, the B&O abandoned the stretch from Adrian to Midvale, with the remaining track between Midvale and Roaring Creek Junction becoming the B&O Midvale Branch. Subsequently, a major track realignment commenced in May 1946 due to the Tygart Valley River flood diversion project, necessitating the construction of a levee and diversion channel west of Elkins, culminating in a new alignment opening in 1948.

The coal mining sector faced significant labor unrest during the 1940s and 1950s, causing sharp declines in coal transportation, which severely affected the railroad's profitability.

In 1957, the B&O established the Heathcliff branch along the Little Kanawha River from Gilmer to Glenville. A construction contract announced on January 10, 1957, included 1.5 miles of track servicing a mine at Trubada, where coal was trucked to a tipple west of Sand Fork. After discovering a substantial coal seam, the B&O extended the line towards the tipple, with the first train movement occurring on July 23, 1959. Coal output along this branch surged to 937,092 tons by 1964 but fell to 596,423 tons by 1966. The mine closed on July 31, 1967, and the Heathcliff branch was abandoned on December 16, 1971.

In the mid-1970s, the route between Charleston and Gassaway was serviced thrice weekly. Due to declining traffic, the B&O sought permission to abandon 28.75 miles from Reamer to Hartland, granted on April 1, 1979. Additional abandonment requests were made in 1985 for 5 miles of mainline from Hartland to Dundon.

Subsequently, CSXT, succeeding the B&O in 1987, filed to abandon 61 miles of track from Gilmer south to Hartland. This decision was partly driven by the Elk Refinery's closure in Falling Rock in 1983, significantly reducing traffic along this route. To prevent the mainline's deterioration, Conrail acquired the line from Charleston to Hartland in 1985 to service a mine at Falling Rock, ensuring access to Union Carbide mines along Blue Creek, which eventually closed in 1990.

B&O Timetable - Charleston Division

Elk River Railroad

The stretch between Gilmer and Hartland faced a promising shift with the announcement of its acquisition by the Elk River Railroad (ER), a subsidiary of the greeting card mogul Bill Bright. The ER also owned the defunct BC&G track extending from the C&C at Dundon to Widen. Bright anticipated that coal from Pittston Coal’s mine at nearby Vandalia would be loaded at Avoca, generating sufficient revenue to maintain both the BC&G and the affiliated ER. The ER planned to launch services on the Gilmer to Hartland line and the Buffalo Creek Railroad (BCG, formerly BC&G) in October 1991. Significant investments were made to upgrade 56 miles of the ER and an additional three miles of the former BCG to meet FRA Class II standards, featuring new ballast and welded rail, enabling empty trains to reach speeds of 14 MPH and loaded trains to 10 MPH. On May 9, 1996, the first revenue operation occurred from the BCG at Avoca, where over 90 cars of coal were transferred via the ER to CSXT at Gassaway. Weekly unit coal trains transported coal to an American Electric Power Plant.

In addition to this acquisition, the ER aimed to acquire an additional 29.8 miles of former B&O tracks from Hartland to Falling Rock, where it could connect to Conrail’s line. This integration would create a direct route extending from CSXT’s line at Burnsville Junction through several locations, including Gilmer, Gassaway, Dundon, Hartland, Falling Rock, and Blue Creek, culminating in Charleston. In 1997, the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) acquired the segment from Charleston to Falling Rock from Conrail.

The ER embarked on restoring the former C&C mainline from Hartland to Reamer on September 15, 1996. Unfortunately, regular operations of the ER were halted after American Electric Power ceased purchasing coal from Pittston Coal’s mine in September 1999. Consequently, on November 15, 2001, a contract was established with Appalachian Railcar Service, with the line from Gassaway to Dundon being utilized for car storage. Gassaway Yard was repurposed for railcar repair and storage.

Today

In 2005, CSXT leased its section from Gilmer to Burnsville to Watco, which subsequently transferred operations to the Appalachian & Ohio Railroad (A&O) in 2006. In 2010, plans were proposed for the Charleston, Blue Creek & Sanderson Railroad to service a coal mine proposed along the former K&WV line on Blue Creek, which would be reactivated.

On May 5, 2019, the state of West Virginia acquired a 62-mile section of dormant track from Clendenin to Frametown from the ER to develop a new linear state park called the Elk River Trail. This initiative aimed to provide a versatile multi-modal pathway for various recreational activities, including hiking, cycling, horseback riding, snowshoeing, and cross-country skiing. Initially, the development of the trail’s first phase targeted a connection from Clendenin to Duck, located at the boundary of Clay and Braxton Counties. By August 2021, 37 miles of the trail had opened, stretching from Frametown to central Clay County, with plans to extend further to Clendenin by the fall.

Subsequently, the ER ceased operations in the winter of 2022, with the last group of stored cars removed from Gassaway Yard in March and the final train running between Gassaway and Gilmer on April 22. During this time, the Elk River Trail was extended from Frametown to Gassaway, achieving a 73-mile trail stretch. It is anticipated that the trail will further extend from Gassaway to Gilmer in the near future. With no active customers on the A&O line from Gilmer to Burnsville, this route is occasionally utilized for rail car storage.

Recent Articles

-

Mother's Day Train Rides: A Complete Guide

Feb 11, 25 12:22 AM

This guide includes -

Coal & Coke Railway: Serving The Heart Of WV

Feb 11, 25 12:08 AM

The Coal and Coke Railway was incorporated in 1902 and served the heart of West Virginia connecting Elkins with Charleston. It was acquired by the B&O in 1916. -

North Station: Boston's Elegant Terminal

Feb 10, 25 08:58 PM

North Station was one of two notable passenger terminals serving Boston with the other being South Station. It opened by the B&M in 1894 and was demolished in 1926. The site still serves trains today…