Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad: Map, Rosters, History

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

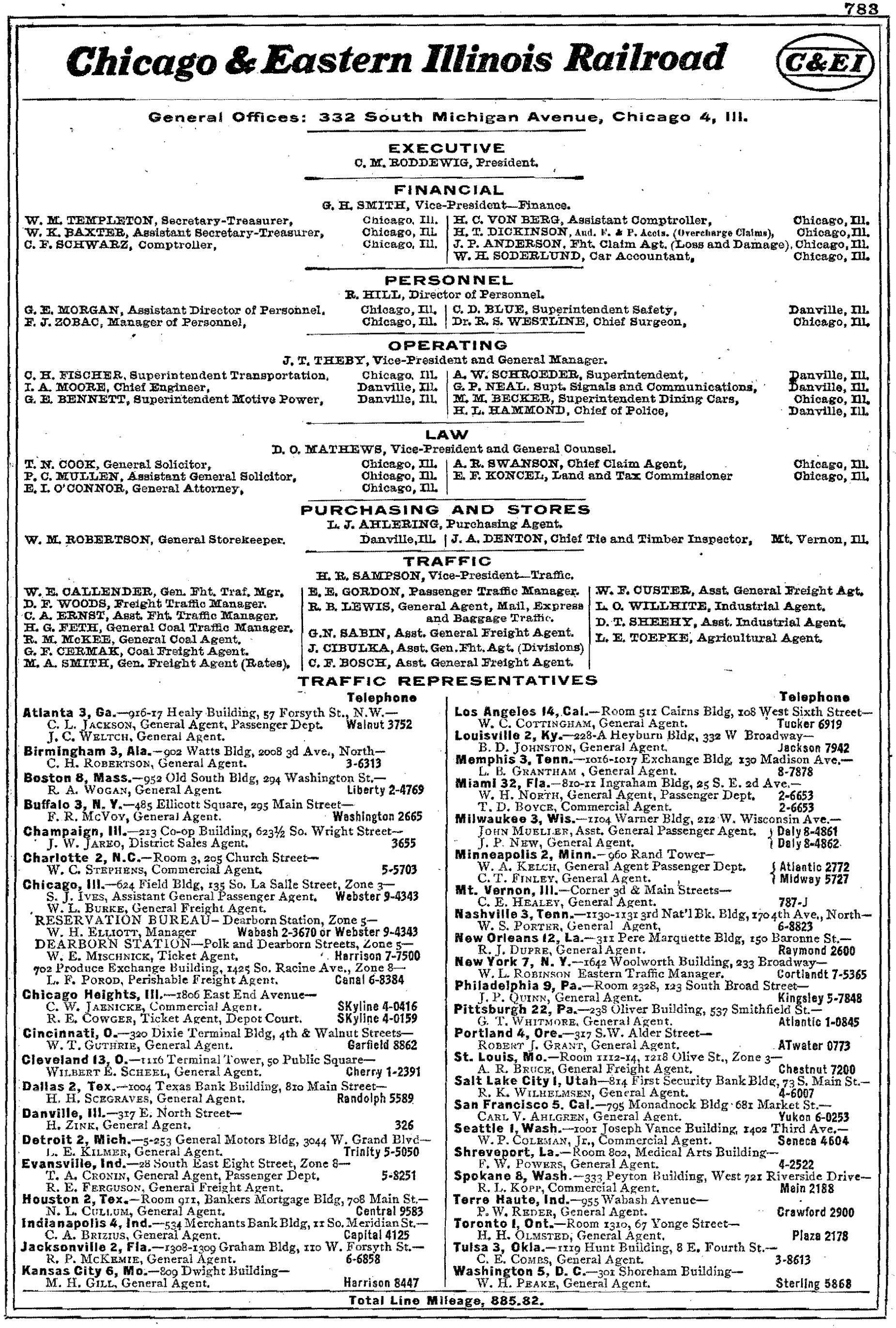

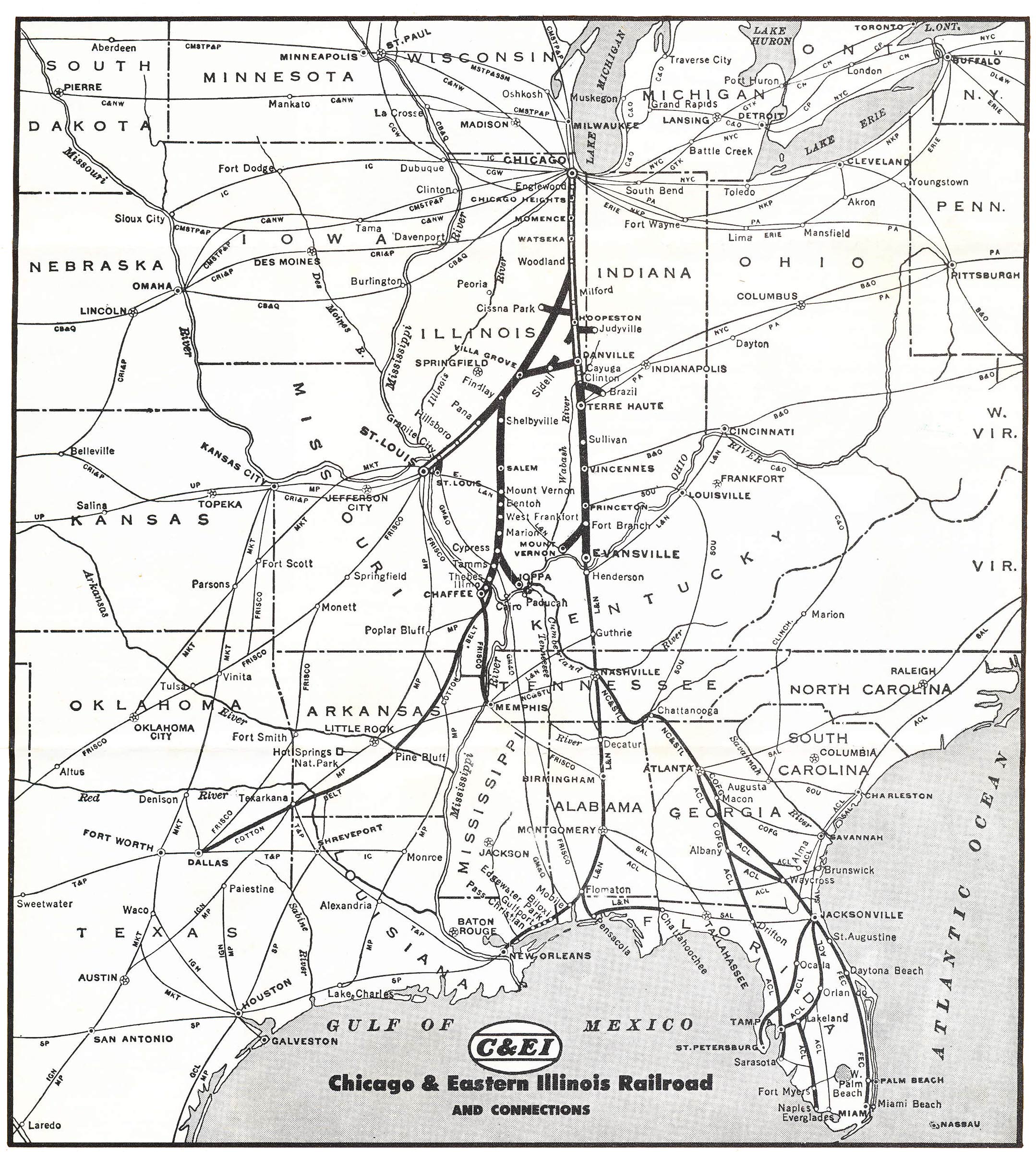

The Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad was a small, Midwestern road situated almost entirely within Illinois; running southward out of the Windy City its main line split at Woodland to reach Evansville and St. Louis.

The railroad once maintained a network of over 1,000 miles and proved a vital connection for the Louisville & Nashville, Floridian passenger services, the movement of coal, and a connection to the Gateway City.

For these reasons, and others, it became a prime target of the much larger trunk lines from the 1870's until disappearing a century later. Poor management under two such owners left it in bankruptcy at various points until a final reorganization during World War II.

When not under another's control the railroad did just fine. By the postwar period a well-maintained and well-managed C&EI showed strong profits, boasting a diversity of traffic that included intermodal by the 1960's.

The company's final chapter was written that decade when the L&N acquired its main line north of Evansville and Missouri Pacific took over the remainder.

Photos

Chicago & Eastern Illinois FP7 #1609 as the combined "Humming Bird"/"Georgian" near the C&WI's 81st Street Tower in Chicago on March 31, 1964. Roger Puta photo.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois FP7 #1609 as the combined "Humming Bird"/"Georgian" near the C&WI's 81st Street Tower in Chicago on March 31, 1964. Roger Puta photo.History

The earliest component of the modern Chicago & Eastern Illinois was the Evansville & Illinois Railroad chartered on January 2, 1849.

According to Willard Anderson's article, "The Century-Old C&EI...," from the August, 1949 issue of Trains Magazine the E&I was formed to connect Evansville, Indiana (located along the north bank of the mighty Ohio River) with Vincennes.

The 53-mile route was completed and ready for service by 1853. The corporate history after this point can become a bit messy or unclear.

According to a small booklet the railroad released in 1957 detailing its corporate heritage, as the E&I was under construction the Wabash Railroad (carrying no connections to the well-known Wabash) was chartered on February 6, 1851 to link Vincennes with Terre Haute.

On November 18, 1852 the Wabash and E&I merged, carrying the latter's name as the Evansville & Illinois. This was short-lived when on March 4, 1853 the railroad was renamed as the Evansville & Crawfordsville.

Then, later that same year service opened to Terre Haute on November 24th. There were hopes of reaching Chicago at this time but the needed funded was never obtained.

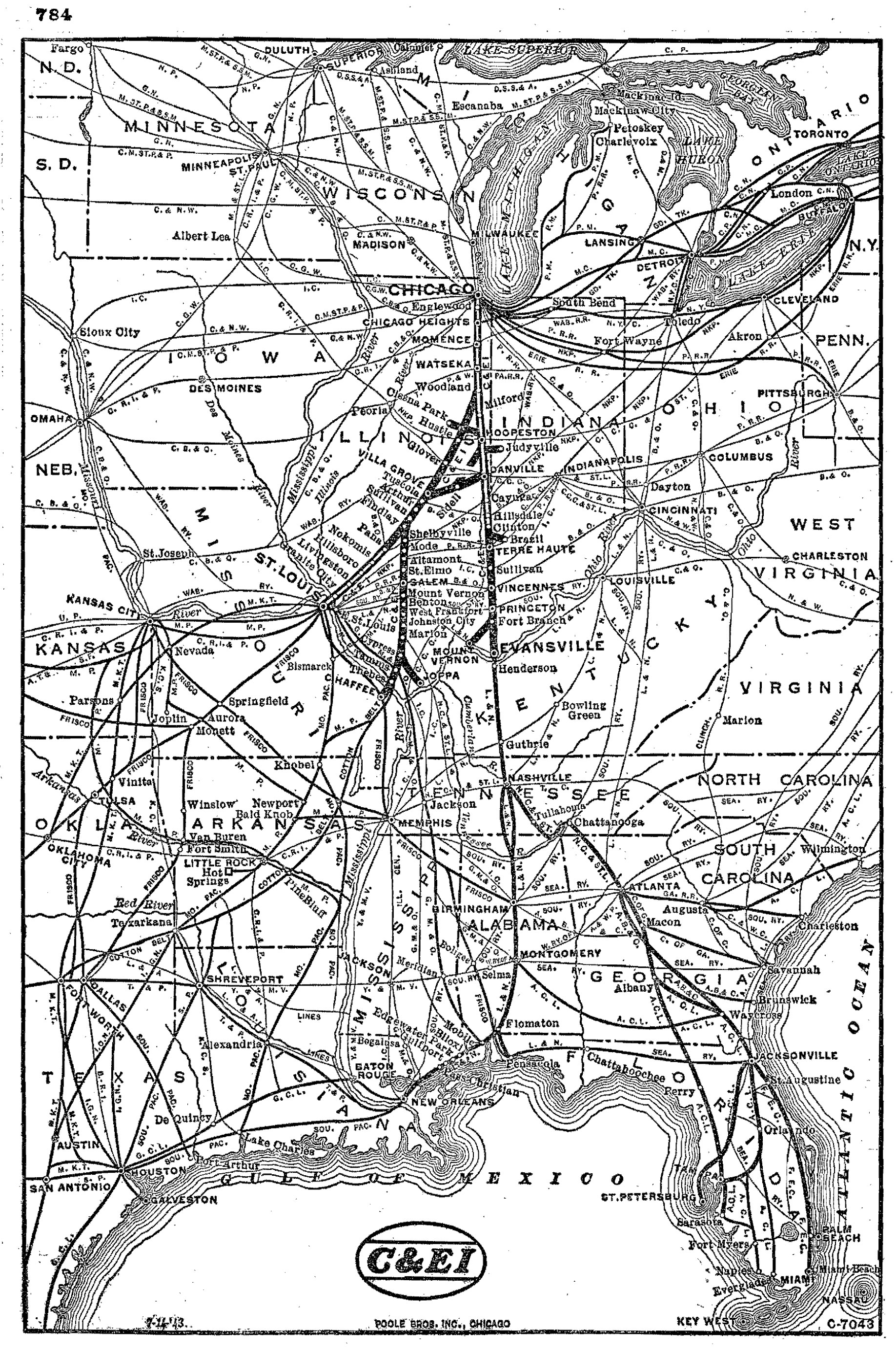

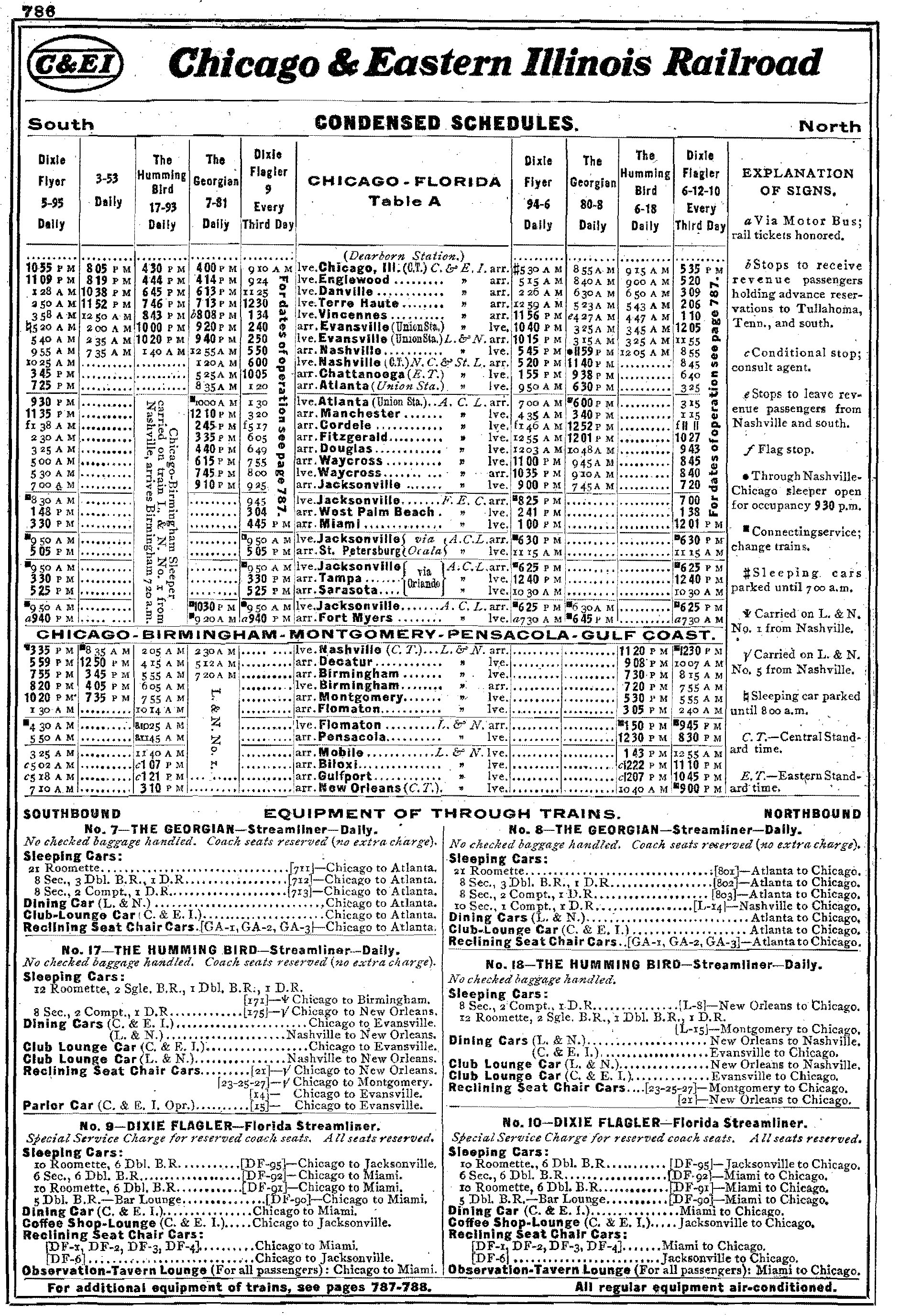

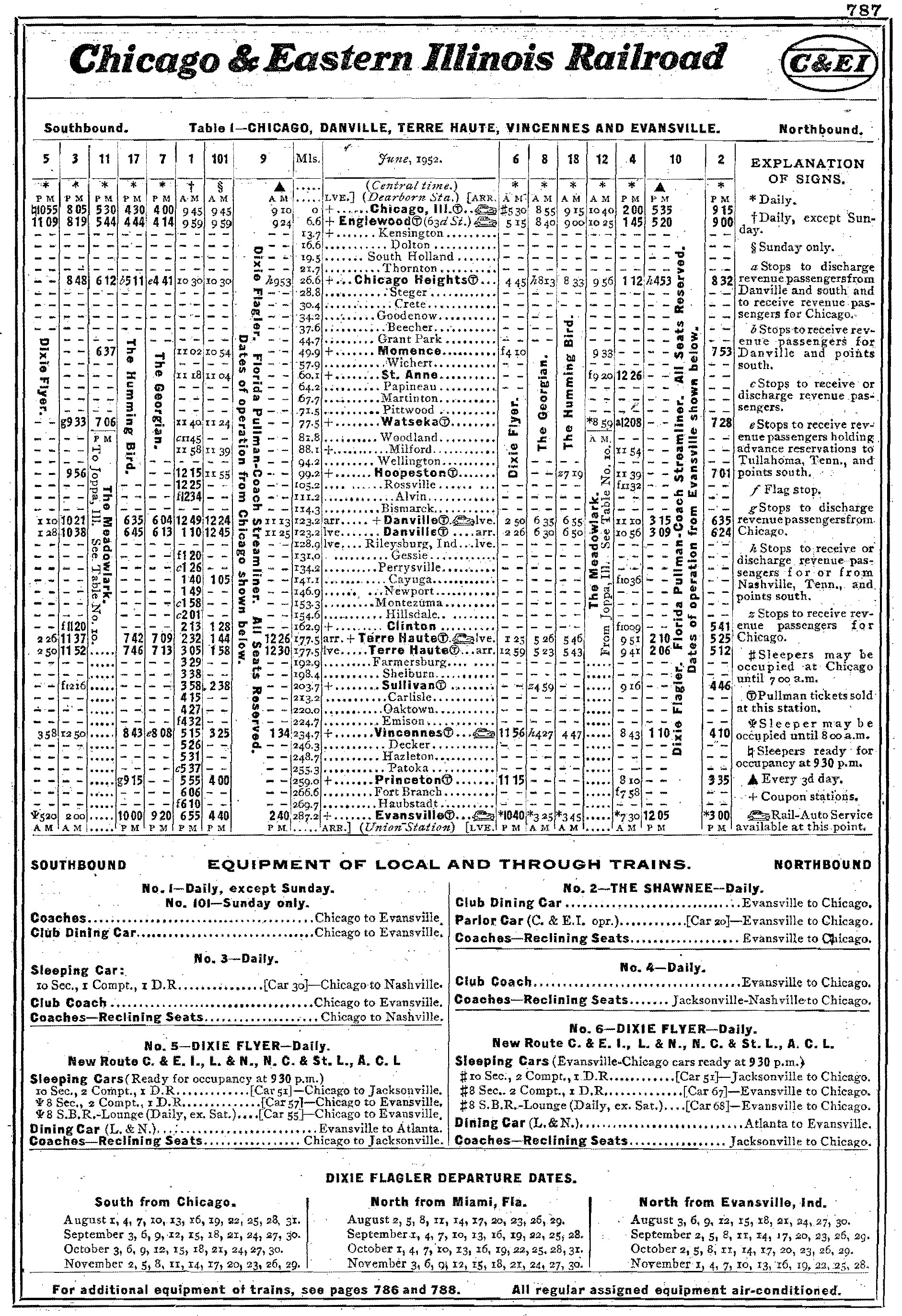

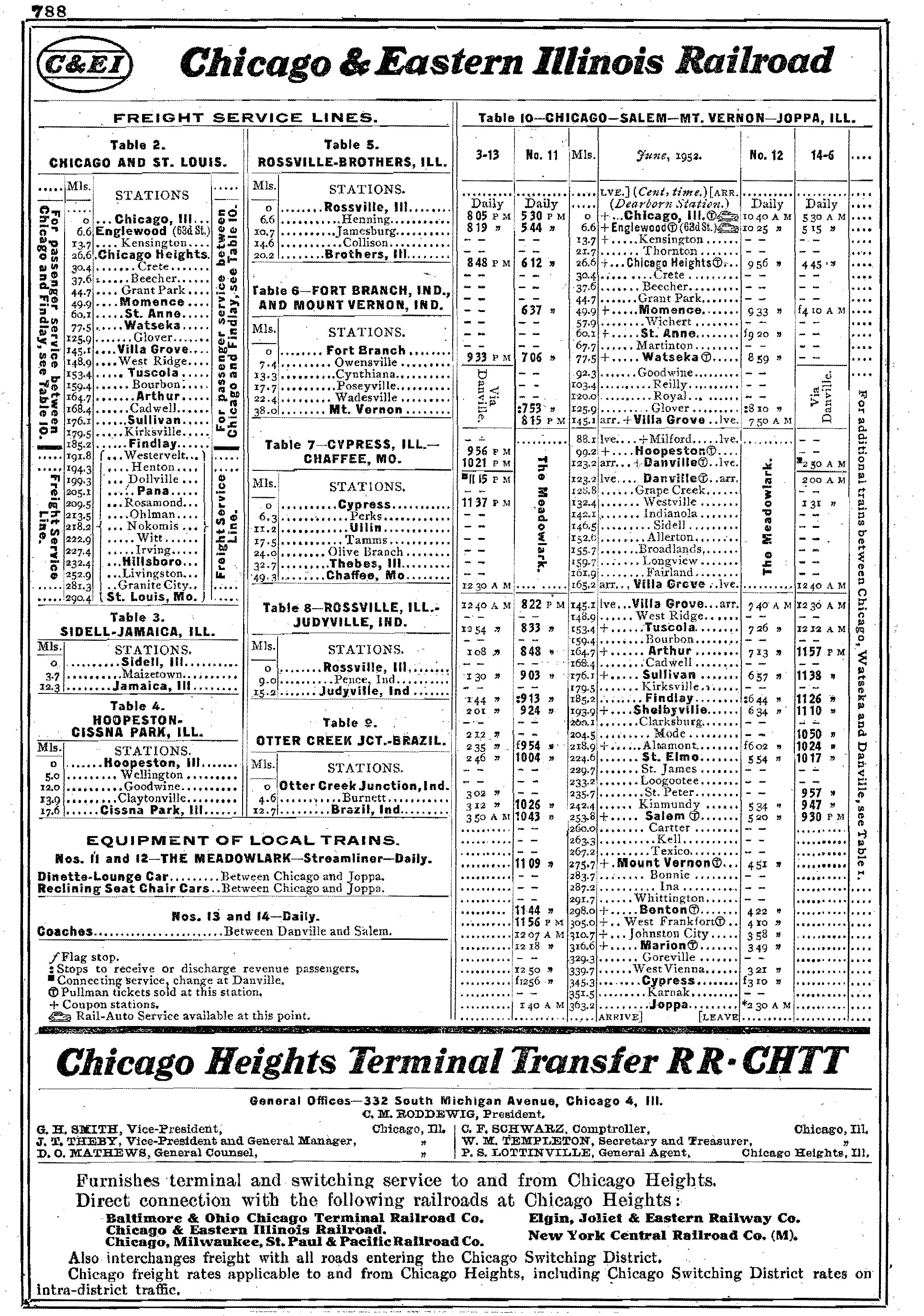

Timetables (1952)

Expansion

The southern component saw no additional construction (there was an Evansville belt line, the Evansville & Terre Haute Company incorporated on May 9, 1881, which joined the C&EI in July of 1911).

The northern segment was originally the Chicago, Danville & Vincennes Railroad organized on February 18, 1865 to complete a route from Chicago into the southern Indiana coal fields.

It began operations between Chicago (running via trackage rights over a Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis subsidiary [PRR] from Lake Street and Western Avenue to Dolton) and Danville in 1871.

In 1875 the road opened its primary engine terminal and maintenance facilities in Danville (Known as the Oaklawn Shops they were closed in 1970 under MP.

During the facility's peak years it featured rip tracks, cars shops, a paint shop, locomotive back shop, and 50-stall roundhouse).

Unfortunately, financial hardships forced the CD&V into bankruptcy and in 1877 it became the Chicago & Nashville Railroad. During August of that year another name change occurred as the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad.

Two years later, in 1879, the C&EI established a direct connection with the Evansville & Crawfordsville (E&C) at Terre Haute when it leased the Evansville, Terre Haute & Chicago (Danville - Otter Creek/Terre Haute), later purchasing the property on December 27, 1899.

Missouri Pacific E9Am #43 (sporting Chicago & Eastern Illinois logos) departs a perilously empty Kansas City Union Station with train #14, bound for St. Louis, circa 1970. This unnamed consist offered only a grill coach and coaches by this date. The locomotive was originally Boston & Maine E8A #3821. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific E9Am #43 (sporting Chicago & Eastern Illinois logos) departs a perilously empty Kansas City Union Station with train #14, bound for St. Louis, circa 1970. This unnamed consist offered only a grill coach and coaches by this date. The locomotive was originally Boston & Maine E8A #3821. American-Rails.com collection.In short order the E&C was also added, thus establishing a through route under common ownership from Chicago to Evansville. The western leg to St. Louis and southern leg through Illinois were also built or acquired in stages. They comprised four primary components.

The first was the Danville & Grape Creek Railroad which opened a short segment from Danville to Westville in 1880. During March of 1881 the C&EI took possession of the property and quickly opened an extension to Sidell. Here, it met the Chicago, Danville & St. Louis building towards Tuscola.

At A Glance

Chicago - Evansville, Indiana Fort Branch - Mount Vernon, Illinois Villa Grove, Illinois - Danville, Illinois Woodland, Illinois - St. Louis Findlay, Illinois - Chaffee, Missouri Cypress - Joppa, Illinois Clinton, Illinois - Brazil, Indiana Hoopeston, Illinois - Cissna Park, Illinois | |

The C&EI purchased this road in November of 1887 and then extended it to Shelbyville, Illinois during December of 1891. Five years later it had reached Altamont.

Between February of 1897 and January of 1899 there were two final additions; the Chicago, Paducah & Memphis extended rails from Altamont to Marion while the Eastern Illinois & Missouri was pushing towards Thebes.

After the C&EI takeover it reached the latter city in 1900. Once a bridge opened across the Mississippi River direct interchange was established with the Illinois Central, Missouri Pacific, St. Louis-San Francisco Railway (Frisco), and St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt) which included trackage rights to Chaffee, Missouri. At the same time a short branch from Cypress to Joppa opened.

Logo

The extension to St. Louis was launched in 1903 following Frisco's involvement, which had acquired control a year earlier. This was not the first time a larger road had taken an interest in the railroad.

According to Gary Dolzall's article, "The Case For The C&EI" from the January 1990 issue of Trains Magazine, going back to 1875 the Illinois Central had courted predecessor Chicago, Danville & Vincennes.

Building southwestward from the Chicago main line at Woodland rails connected with the Chaffee/Joppa branch at Villa Grove and was then extended from Findlay to Pana.

As work continued an agreement was reached with the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis (the "Big Four," a New York Central subsidiary) to use its tracks as far as Granite City. From there, additional rights were granted over the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis (TRRA) which provided the C&EI direct access into the Gateway City.

At its peak the railroad operated an 1,175 network (including trackage rights); 909 miles were deemed main line while 266 carried secondary status.

The Dolton Junction (Chicago) to Clinton, Indiana section was later double-tracked, protected by automatic train stop and the remainder to Evansville guarded by Centralized Traffic Control (CTC). Direct entry into Chicago, north of Dolton Junction, was via the Chicago & Western Indiana.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois SW1 #96 is seen here tied down during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois SW1 #96 is seen here tied down during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.The Frisco's involvement began a tough stretch for the C&EI. The railroad was generally profitable but grand schemes by others sank it into bankruptcy twice. The Frisco, of course, wanted it as a Chicago connection but that carrier's collapse in May of 1913 also brought down the C&EI.

Once reorganized and independent in 1920 the road enjoyed a few years of relative success, in part thanks to coal. The southern Indiana fields at this time generated some 10 million tons annually. However, a 1922 strike greatly hurt the market price from which the coal here never truly recovered.

System Map (1940)

For the C&EI this resulted in tonnage being slashed by two-thirds. After the strike black diamonds remained an important commodity but never exceeded more than one-third of the railroad's annual tonnage.

For instance, Mr. Anderson's article notes that for 1948 its traffic (comprising 10.9 million total tons) was as follows: coal 35.8%, manufacturing 34.3%, agriculture 10%, and the remainder various miscellaneous movements.

In 1928 the C&EI was again acquired when the Van Sweringen's growing railroad empire, through their Chesapeake & Ohio affiliate, took over the property.

Passenger Trains

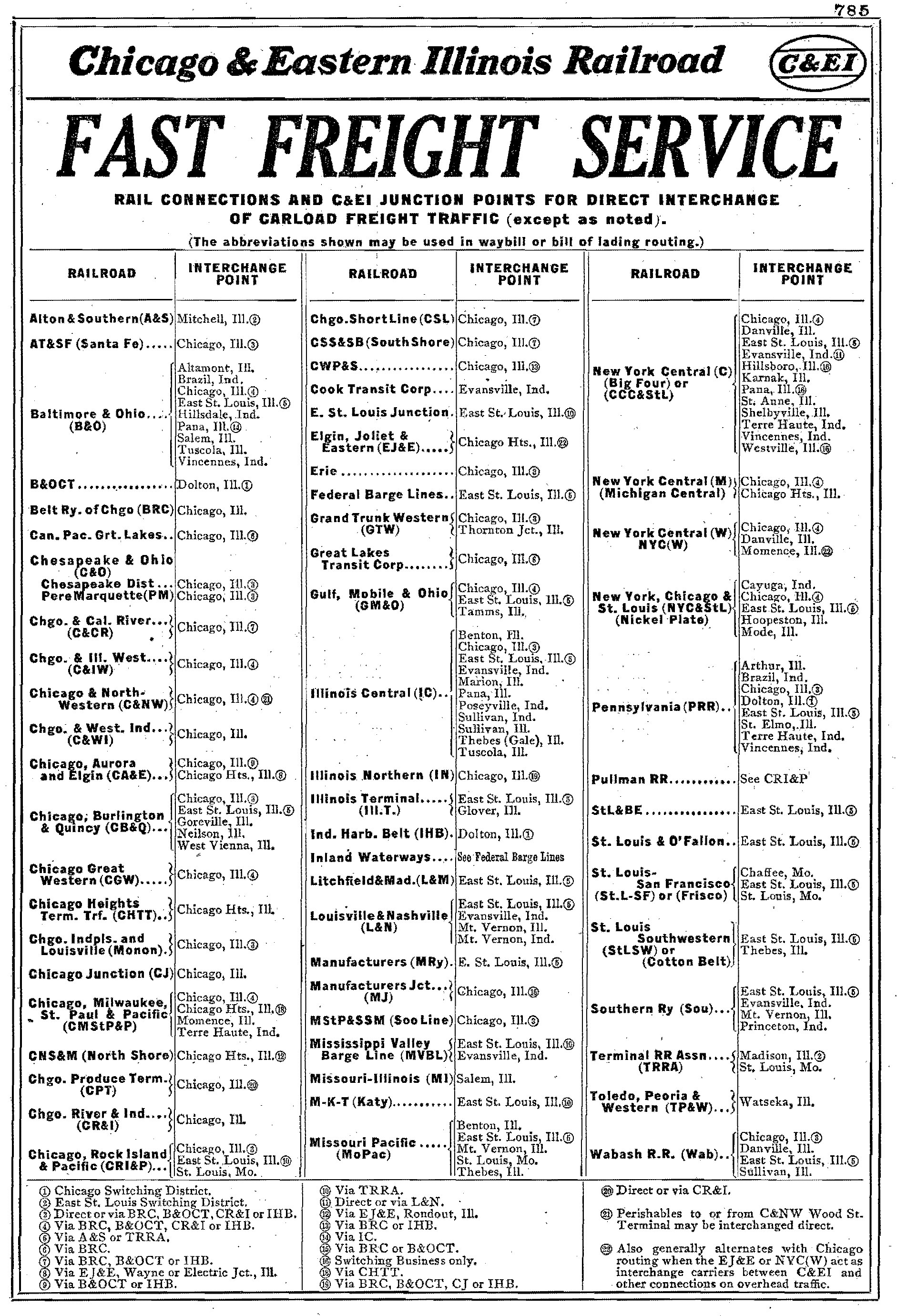

The C&EI did operate its own streamliners although is best remembered for the through services to Florida which operated in tandem with the L&N, Florida East Coast, Atlantic Coast Line, Central of Georgia, and Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis.

In 1946 it took delivery of two, lightweight trainsets from Pullman for its own streamlined operations; one was a four-car consist named the Meadowlark (mail-baggage/grille car with three coaches) and the other the seven-car Whippoorwill (combine, four coaches, diner, and parlor-lounge-observation).

They were clad in a striking blue livery with gold/orange trim. The railroad's history with streamlining actually began years before either of these trains launched.

In 1940, as part of the Dixie Flagler service hosted by the C&EI/L&N/NC&StL/Atlanta & Birmingham Coast/ACL/FEC the railroad unveiled a modest but striking shroud worn by 4-6-2 #1008 (K-2), a product of its own Oaklawn Shops (a project carried out for a modest $2,300).

The Pacific featured a mostly aluminum/stainless-steel look with black trim and red-pinstripes. Mr. Dolzall notes that a 1941 grade-crossing incident changed the front-end to a bullet-nose appearance and the locomotive lost its shrouding entirely by 1943. The C&EI's passenger business remained strong through World War II as it average more than two-million train miles.

Afterwards, however, that all changed. In 1949 it discontinued service to St. Louis and by 1960 losses were mounting, in part due to the L&N's growing disinterest.

In 1968 the combined Humming Bird/Georgian was discontinued and the last remaining train still running before L&N's takeover was the Chicago-Danville local consisting of just a few cars.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois FP7 #1608 departs Chicago with train #93, the combined southbound "Georgian"/"Hummingbird," circa 1966.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois FP7 #1608 departs Chicago with train #93, the combined southbound "Georgian"/"Hummingbird," circa 1966.All C&EI trains used Chicago's Dearborn Station

Cardinal: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Century of Progress: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Chicago-Nashville Limited (L&N): (Chicago - Nashville)

Chicago Express (L&N): (Chicago - Birmingham)

Chicago-St. Louis Express: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Chicago-St. Louis Limited: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Chicago-St. Louis Special: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Curfew: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Danville-Chicago Flyer: (Chicago - Danville)

Dearborn: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Dixiana (L&N/NC&StL/A&BC/ACL/FEC): (Chicago - Miami)

Dixie Express (L&N): (Chicago - New Orleans)

Dixie Flagler (L&N/NC&StL/A&BC/ACL/FEC): (Chicago - Atlanta - Miami)

Dixieland (L&N/NC&StL/A&BC/ACL/FEC): (Chicago - Atlanta - Miami)

Dixie Limited (L&N/NC&StL/CoG/ACL): (Chicago - Jacksonville)

Egyptian Zipper: (Danville - Cypress - Joppa)

Evansville-Chicago Express: (Chicago - Evansville)

Georgian (L&N/N&CStL): (Chicago - Atlanta)

LaSalle: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Meadowlark: (Chicago - Cypress)

Nashville-Chicago Limited (L&N): (Chicago - Nashville)

New Dixieland (L&N/NC&StL/ACL/FEC): (Chicago - Miami)

New Orleans Special (L&N): (Chicago - New Orleans)

St. Louis-Chicago Express: (Chicago - St. Louis)

St. Louis-Chicago Limited: (Chicago - St. Louis)

St. Louis-Chicago Special: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Shawnee: (Chicago - Evansville)

Silent Knight: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Spirit of Progress: (Chicago - St. Louis)

Whippoorwill: (Chicago - Evansville)

Zipper: (Chicago - St. Louis)

The above passenger service listing is courtesy of Gary Dolzall's article, "The Case For The C&EI" from the January 1990 issue of Trains Magazine.

This time the onset of Great Depression brought financial ruin and the company again found itself in bankruptcy by 1933.

It slowly recovered from these lean years, then witnessed record traffic during World War II that saw net profits reach nearly $3 million according to William Gregory and Robert St. Clair's article, "You Can't Keep A Good Railroad Down!" from the October, 1954 issue of Trains Magazine.

On January 17, 1941 it officially emerged from receivership. While wartime traffic helped immensely so did the efforts of receiver John Walker Barriger III (best known for his years leading the Monon) who helped restructure its debt and financing.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois F3A #1201 lays over between assignments in Mitchell, Illinois on November 3, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois F3A #1201 lays over between assignments in Mitchell, Illinois on November 3, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.Into the 1950's the railroad fought sagging coal traffic by looking for other business primarily in the form of agriculture, trailer-on-flatcar/TOFC (the so-called Piggyback Flyers were hotshots which ran overnight from Chicago to the L&N connection), and manufacturing.

These efforts did help turn immediate postwar losses into strong profits although the road's regional status left it vulnerable.

One way in which it improved its postwar slump was through the retirement of steam, quietly carried out on May 5, 1952 when 2-8-2 #1944 finished up switching chores that day. The iron horse was replaced largely with Electro-Motive products as well as a few examples from Baldwin and Alco.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH-660 | 102 | 1938 | 1 |

| S1 | 103-105, 106 (Ex-StL&OF) | 1941-1946 | 4 |

| RS1 | 115-118 | 1945 | 4 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-660 | 110 | 1942 | 1 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW1 | 95-99 | 1942 | 5 |

| SW | 100-101 | 1938 | 2 |

| NW2 | 119-124 | 1949 | 6 |

| SW7 | 126-133 | 1950 | 8 |

| BL2 | 200-201 | 1948 | 2 |

| BL1 | 202 | 1948 | 1 |

| GP7 | 203-232 | 1950-1951 | 30 |

| GP9 | 221 (Second), 229 (Second), 233-238 | 1956-1958 | 8 |

| GP30 | 239-241 | 1963 | 3 |

| GP35 | 242-272 | 1964-1965 | 31 |

| E7A | 1100-1102 | 1946 | 3 |

| E9A | 1102 (Second) | 1958 | 1 |

| F3A | 1200-1205, 1400-1409 | 1948-1949 | 16 |

| F3B | 1300-1301, 1500-1504 | 1948 | 7 |

| FP7 | 1600-1609 | 1949 | 10 |

Steam Roster (As Of 1949)

| Class | Road Number(s) | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-6 | 889-959 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| K-1 | 1001-1003 | 4-6-2 | Baldwin | 1910 |

| K-2 | 1008-1015 | 4-6-2 | Baldwin | 1911 |

| K-2 | 1016-1017 | 4-6-2 | Alco | 1913 |

| K-3 | 1018-1023 | 4-6-2 | Lima | 1923 |

| K-3 | 1018-1023 | 4-6-2 | Lima | 1923 |

| N-4 | 1900-1924 | 2-8-2 | Alco | 1912 |

| N-2 | 1925-1939 | 2-8-2 | Alco | 1918 |

| N-3 | 1940-1959 | 2-8-2 | Alco | 1922-1923 |

The above steam roster is courtesy of Willard Anderson's article, "The Century-Old C&EI...," from the August, 1949 issue of Trains Magazine.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois GP35 #272 leads a northbound freight out of Granite City, Illinois on May 1, 1964. American-Rails.com collection.

Chicago & Eastern Illinois GP35 #272 leads a northbound freight out of Granite City, Illinois on May 1, 1964. American-Rails.com collection.Merger and Breakup

The possibility of merger reignited at this time as discussions were carried out with everyone from the Louisville & Nashville, Illinois Central, and Missouri Pacific to the Monon and Chicago Great Western. Things remained unchanged until 1967 when the Missouri Pacific's stock control grew increasingly larger.

This time there would be no return to independence. By 1970 it had majority and formally consolidated the C&EI into its network during 1976.

In 1969 the L&N gained its long-coveted entry into Chicago by picking up the Woodland Junction - Evansville segment (206 miles) then utilized MoPac trackage rights to reach the Windy City.

For such a small road with numerous twists and turns throughout its corporate history the C&EI held an important place within the industry thanks to its Chicago connection.

Today, the MP has since been acquired by the vaunted Union Pacific. However, the principal C&EI lines still play an important part in the UP’s network, including the Evansville segment which is presently utilized by L&N successor CSX Transportation.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Oregon Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 03:11 PM

With its rich tapestry of scenic landscapes and profound historical significance, Oregon possesses several railroad museums that offer insights into the state’s transportation heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 02:56 PM

Today, several museums in North Caorlina preserve its illustrious past, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of railroads with artifacts, model trains, and historic locomotives. -

New Jersey Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 25, 25 11:48 AM

New Jersey offers a fascinating glimpse into its railroad legacy through its well-preserved museums found throughout the state.