West Virginia Central Railroad: Preserving WV Rail Lines

Last revised: September 6, 2024

By: Adam Burns

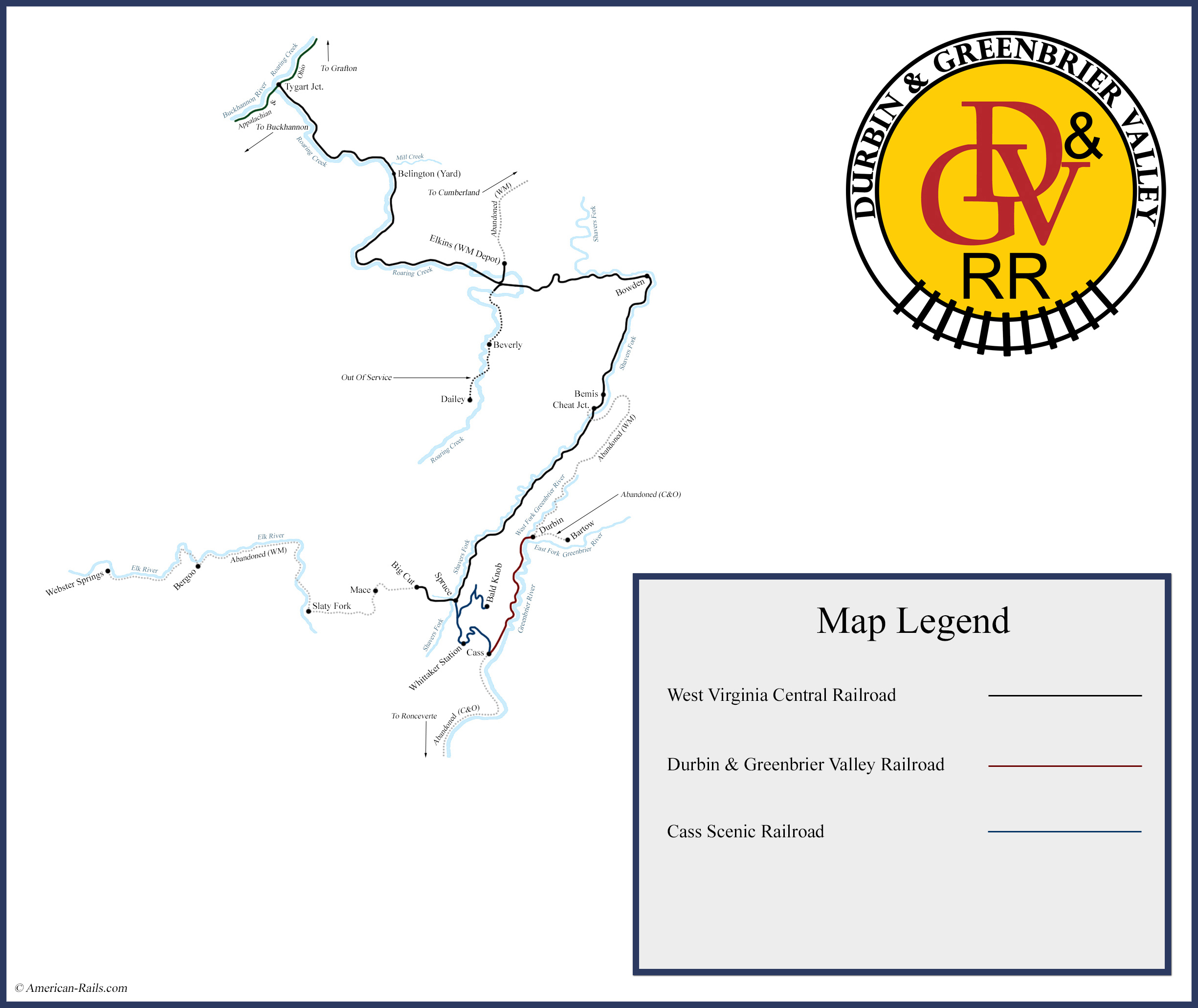

The state-owned West Virginia Central Railroad (WVC), operated by the Durbin & Greenbrier Valley, has blossomed into one of the Mountain State's top tourist attractions.

Thousands of visitors descend into downtown Elkins annually to ride its trains which depart from the city's restored Western Maryland (WM) depot.

Many years ago, the WM maintained a significant presence in the area serving coal mines, tanneries, logging/timber companies, and other local industries.

As its southern hub, lines radiated north, south, and west of Elkins to reach small communities like Belington, Durbin, and Webster Springs.

Today, this corridors still exist thanks to the state's foresight. The WVC's public trips offer fresh meals served on board, spectacular views of the Appalachian Mountains, and even overnight get away packages.

Its top trains include the New Tygart Flyer, Cheat Mountain Salamander, and Mountain Explorer Dinner Train. The railroad also hosts special events during the holidays.

As an active short line freight railroad, the WVC maintains a connection with Appalachian & Ohio Railroad (a CSX Transportation subsidiary) at Tygart Junction.

Western Maryland BL2 #82 crosses Bridge 77 at Cheat Bridge, West Virginia with a photo freight on October 12, 2014. Loyd Lowry photo.

Western Maryland BL2 #82 crosses Bridge 77 at Cheat Bridge, West Virginia with a photo freight on October 12, 2014. Loyd Lowry photo.History

After its creation in 1986, CSX Transportation began systematically selling off or abandoning large blocks of its system deemed either redundant or unprofitable.

This included hundreds of miles in northern West Virginia that had long been important components of the Baltimore & Ohio and Western Maryland.

Many of these lines handled predominantly coal although not all; in 1985, then-Chessie System abandoned a section of the B&O's St. Louis main line while that same year WM's "Thomas Subdivision," its main line linking Elkins with Cumberland, Maryland was hit by severe flooding.

In response, Chessie System/CSX refused to repair the damage and it sat embargoed until abandoned a few years later.

A few years prior, in 1979, when the Chesapeake & Ohio abandoned its Greenbrier Subdivision (today's Greenbrier River Trail) the Durbin Branch became unneeded and it, too, was abandoned.

This left lines located north, south, and west of Elkins as the only remaining sections of the old Western Maryland still intact (CSX was able to continue accessing them via the B&O from Tygart Junction/Belington).

These lines included the Belington Subdivision (Elkins-Belington), Durbin Subdivision (Elkins-Elk River Junction, the remainder to Durbin was abandoned), Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk Railroad/GC&E Subdivision (Elk River Junction-Webster Springs), and the Dailey Branch (Elkins-Dailey).

During the 1990's, CSX continued scaling back operations. It petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon all remaining WM trackage.

According to Matt Reese's former website, Northern West Virginia Railroads, the state subsequently stepped in to save the corridor. He states:

"The West Virginia Central Railroad was inaugurated on May 16th, 1998, during the annual Cass Scenic Railroad railfan weekend.

This marked the end of several years of legal battles to save over 140 miles of abandoned CSX track stretching south through north central West Virginia, which CSX had been trying to abandon since the early 1990's when its coal traffic had dried up.

Finally in 1997 the ICC allowed CSX to abandon its track below Elkins with the condition that the line's rail would be left down allowing the West Virginia State Rail Authority (WVSRA) to buy the abandoned portion between Elkins and Bergoo along with the still in service section between Elkins and Tygart Junction for $6 million.

However, instead of operating the new West Virginia Central line itself, the WVSRA sought an outside company to [manage] and operate the railroad.

After receiving several bids, the WVSRA decided to award the job to the Durbin and Greenbrier Valley Railroad, a shortline railroad company owned by John and Kathy Smith. Fortunately, the D&GV is not the average railroad, in the sense they know how to get things done - and get them done right.

The West Virginia Central's terminal is found at Belington. Built on the site of the old yard, the WVC erected a single stall engine house here in the fall of 1998. The company's locomotives and passenger equipment can also be found there, after hours and during the excursion off season."

Chesapeake & Ohio F7A #7094 leads a photo freight along the Along the bank of the Cheat River's Shavers Fork during a fall afternoon. The covered wagon was originally built as Milwaukee Road #109-A in 1950. Loyd Lowry photo.

Chesapeake & Ohio F7A #7094 leads a photo freight along the Along the bank of the Cheat River's Shavers Fork during a fall afternoon. The covered wagon was originally built as Milwaukee Road #109-A in 1950. Loyd Lowry photo.The West Virginia Central has grown immensely over the last twenty years thanks to the efforts of husband and wife team, John and Katy Smith.

WVC's latest milestone includes moving its headquarters to the Western Maryland depot in Elkins; here, the WM once maintained a large yard, roundhouse, and other maintenance facilities.

This terminal acted as its primary staging location where coal, lumber, and other freight was marshaled before being sent north to Cumberland or south to Durbin.

After CSX left town it removed all track and remaining buildings, including the bridge in 1989. Seeing the property's potential, the WVC and city began exploring ways to return rails to the site in the early 2000's.

While it was impossible to reuse the entire yard for rail purposes both parties agreed a dual-use plan for the grounds would be best.

After funding was secured the bridge was quickly rebuilt and a dedication ceremony held in May, 2006.

There are currently two staging tracks serving the station; nearby is an amphitheater and not far away can be found a restaurant (The Rail Yard), hotel (Holiday Inn Express), and gas station (Go-Mart). While the old roundhouse foundation and turntable pit remain, plans to rebuild this structure by the West Virginia Railroad Museum fell through.

A West Virginia autumn is a breathtaking wonder of natural. Here, Western Maryland BL2 #82 and Chesapeake & Ohio F7A #7094 lead a photo freight at High Falls. Loyd Lowry photo.

A West Virginia autumn is a breathtaking wonder of natural. Here, Western Maryland BL2 #82 and Chesapeake & Ohio F7A #7094 lead a photo freight at High Falls. Loyd Lowry photo.Building A Railroad To Elkins

The city of Elkins, West Virginia owes its existence to the railroad. The area was formerly a small farming community known as Leadsville where agriculture was shipped by boat down the Tygart Valley River.

Rail service to this remote region would likely never have happened without Henry Gassaway Davis.

According to the book, "The Western Maryland Railway: Fireballs & Black Diamonds," by authors Roger Cook and Karl Zimmermann, the banker and businessman from Piedmont, Maryland believed rich sources of coal and timber could be found within the Upper Potomac River Valley, and the only way to efficiently extract them was a railroad.

With political connections he convinced West Virginia state legislatures to approve a charter for the Potomac & Piedmont Coal & Railroad Company (P&PC&RR) in 1866.

In addition to a railroad, the new company was allowed to build sawmills, sell real estate, produce brick, manufacture lumber, mine coal, construct furnaces, and erect other factories.

After more than a decade the P&PC&RR finally began construction in April, 1880. It headed south from a connection with the Baltimore & Ohio near Bloomington, West Virginia (later known as West Virginia Central Junction)along the Potomac River's North Branch.

Its initial goal was to handle coal, a task accomplished in 1881 when it reached a mine near Elk Garden, West Virginia.

That same year, Davis renamed the Potomac & Piedmont Coal & Railroad as the West Virginia Central & Pittsburgh Railway (WVC&P) to better reflect far greater ambitions; to the south he sought expansive rail service along the Cheat, Greenbrier, and Tygart Rivers while to the north a Cumberland/Pittsburgh connection.

The company's leadership included President Henry Davis, Vice-President Stephen B. Elkins, directors William Keyser, Alexander Shaw, James Blaine, and John Hambleton.

Many of these individuals were responsible for West Virginia's early economic development Continuing south from Elk Garden, rails reached Fairfax in May, 1884 and then Davis (via Thomas) by November 1st.

With this extension the WVC&P's traffic diversified immensely as it branched out into logging, served a tannery, pulp mills, and sawmills.

It also handled coke from ovens run by a Davis subsidiary, the Davis Coal & Coke Company, via coke ovens at Thomas and Coketon.

While the railroad had always intended to push northward it was also driven by the B&O's hostility (its only connection), which dictated interchange freight rates and tried to block its expansion.

Under a new subsidiary, the Piedmont & Cumberland Railway (P&C), Davis headed north from West Virginia Central Junction in 1886, intent on reaching Cumberland where a connection could be made with the Pennsylvania Railroad's Georges Creek & Cumberland and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.

After winning a fight against the B&O, WVC&P's first train reached Cumberland (via Westernport) on July 16, 1887.

As this was ongoing the company also eyed expansion south from Thomas. Try as they might, the only suitable grade engineers could locate was down the beautiful, but extremely rugged, Black Fork Canyon.

The location of today's breathtaking Blackwater Falls State Park, the grade exceeded 3% in several locations and would prove an operational headache until its abandonment in the 1980's.

In 1888, the WVC&P arrived in Parsons, a unique community whose downtown location is partially situated within a narrow strip of land near the confluence of the Cheat River's Black and Shavers Forks.

This distinctive formation forced the railroad to build two bridges within a few hundred feet of each other. In late 1889, rails arrived in Elkins.

After establishing a small yard and terminal here (which became WM's primary staging location in the Mountain State), Davis focused on building a series of feeder lines.

In 1891, a 16-mile spur was opened northwesterly to Belington, which became an important southern/western interchange with the Baltimore & Ohio after that railroad standard-gauged its own branch to the town in 1892.

What became its Dailey Branch was finished in stages, opening to Beverly (south of Elkins) in November, 1891 and then to Huttonsville in 1899.

Baltimore & Ohio GP9 #6530 departs the Elkins depot over the restored bridge spanning the Roaring Creek (rebuilt in 2006) with the "Cheat Mountain Salamander" bound for the old logging town of Spruce. Loyd Lowry photo.

Baltimore & Ohio GP9 #6530 departs the Elkins depot over the restored bridge spanning the Roaring Creek (rebuilt in 2006) with the "Cheat Mountain Salamander" bound for the old logging town of Spruce. Loyd Lowry photo.Its eventual plan for this latter corridor was to reach some point along the Chesapeake & Ohio for a southern interchange.

However, due to high forecasted construction costs and the C&O's own plan to build a branch far up the Greenbrier River (to serve West Virginia Spruce Lumber Company's [a division of West Virginia Pulp & Paper] logging operations near Cass), the project was abandoned.

Instead, Davis organized the Coal & Iron Railway in December, 1899 to meet this new C&O line. It headed east from Elkins, turning south near Bowden.

It was a difficult route riddled with grades exceeding 2%. In addition, two tunnels were needed. After four years of work the C&I was completed to Durbin on July 27, 1903 according to William McNeel’s book, “The Durbin Route.”

From the station in Elkins the route’s entire length spanned 46.9 miles. Under the WM it was known as the Durbin Subdivision or Durbin Branch. The C&O would reach Durbin, itself, in December, 1903

To haul logs from the western slopes of Shavers Mountain, West Virginia Pulp & Paper chartered a standard-gauge common-carrier, the Greenbrier & Elk Railroad.

The G&E split from the Durbin Subdivision at a location the Western Maryland referred to as Elk River Junction (near Bemis).

Passenger trains are not the only found on the West Virginia Central, the railroad also provides general freight service. Here, F7A #4094 leads covered hoppers and open gondolas at Tygart Junction, West Virginia. Loyd Lowry photo.

Passenger trains are not the only found on the West Virginia Central, the railroad also provides general freight service. Here, F7A #4094 leads covered hoppers and open gondolas at Tygart Junction, West Virginia. Loyd Lowry photo.Its first section from Cass to Spruce (8 miles) featured very stiff grades, requiring the use of Shay geared steam locomotives.

This now-ghost town once boasted a pulp peeling mill, company store, railroad facilities, and housing.

In 1910 the railroad was renamed the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk (GC&E) and continued expanding, connecting with the Coal & Iron at Cheat Junction to the north and running as far west as Bergoo.

At its peak the GC&E maintained some 175 miles, earning it recognition as the longest logging railroad in the country. The Western Maryland acquired control of the GC&E's in 1927, which became its Elk River Branch (or GC&E Subdivision).

The WM's interest in the property lay primarily in expanded coal operations. It upgraded the line with heavier rail, improved ballasting, and reduced curves. Nevertheless, the line still retained its rugged profile.

Even into the modern diesel era it proved an extremely difficult stretch of railroad. Incredibly, the WM expanded beyond the rural hamlet of Bergoo to further expand its coal business.

In 1929 it acquired the narrow-gauge West Virginia Midland Railroad, which proved to be WM's most isolated segment.

Diesel Locomotive Roster

| Number | Model | Builder | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | VO-1000 | Baldwin | 8/1943 as U.S. Army #7143, later Middle Fork Railroad #11 |

| 39 | ML-8 | Whitcomb | 1939, as U.S. Navy #65-00227 |

| 67 | FP7 | EMD | 2/1952 as Clinchfield #200* |

| 82 | BL2 | EMD | 10/1948 as Western Maryland #82 |

| 92 | E8A | EMD | 9/1950 as Baltimore & Ohio #92/#1440 |

| 207 | S2 | Alco | 2/1942 as Manufacturers Railway #207** |

| 243 | FP7 | GMDD | 9/1952 as Canadian Pacific #4071*** |

| 302 | FA-2 | Alco | 1/1951 as Western Maryland #302 (Became cab car for Long Island Railroad.) |

| 303 | FA-2 | Alco | 1/1951 as Western Maryland #303 (Became cab car for Long Island Railroad.) |

| 415 | F7B | EMD | 6/1950 as Nashville, Chattanooga & St Louis #918*** |

| 6153 | GP9 | EMD | 11/1956 as Chesapeake & Ohio #6153 |

| 6532 | GP9 | EMD | 6/1957 as Baltimore & Ohio #6532 |

| 6641 | GP9 | EMD | 5/1954 as Texas & New Orleans #283***** |

| 7094 | F7A | EMD | 12/1950 as Milwaukee Road #109-A****** |

* Later became Seaboard System #118 and CSX #118/#418. Currently lettered and painted as Western Maryland #67 in the "Speed Lettering" livery.

** Later became Bentley Coal Company #207. Currently in storage.

*** Lettered and painted as Western Maryland #243 in the "Speed Lettering" livery.

**** Later became CSX #117. Lettered and painted as Western Maryalnd #415 in the "Speed Lettering" livery.

***** Later became Southern Pacific #5893, #3422, and #3010. Currently lettered and painted as Baltimore & Ohio #6641.

****** Lettered and painted as Chesapeake & Ohio #7094

Steam Locomotive Roster

| Railroad/Number | Arrangement/Class | Builder/Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preston Railroad #18* | 2-8-0 | Baldwin, 1904 | Cass, WV** |

| Preston Railroad #19* | 2-8-0 | Baldwin, 1906 | Cass, WV** |

* Later sold to the West Virginia Northern Railroad.

** Stored, possible static display.

*** Stored, possible restoration candidate.

After rapidly expanding his empire over a two-decade period, Davis abruptly sold out to George Gould on November 1, 1905.

The younger Gould's interest in the WVC&P was to act a feeder system into the original Western Maryland, which would act as the eastern component in a true, coast-to-coast transcontinental railroad.

This dream ultimately failed although Gould is credited with piecing together the modern Western Maryland Railway. To learn more about its history please click here.

Today, the state of West Virginia owns and maintains most the WM's lines around Elkins, running as far as Spruce/Big Cut where it connects with the Cass Scenic Railroad.

There were plans to remove this rail and relay it along the former Durbin Branch between Elkins and Durbin (today's West Fork Rail/Trail). Had this occurred, visitors would have been able to enjoy a complete round trip from Elkins to Cass by rail, and return via Spruce.

Unfortunately, Mr. Smith deemed the project too expensive due to costs associated with repairing Tunnel #2 at Glady, located just east of Cheat Junction.

To the delight of railfans the WVC operates some of the most unique diesel equipment you can find anywhere, including a rare BL2, of Western Maryland heritage. All in all, the future certainly looks bright for this little short line in West Virginia!

One of the nation's most popular versions of official "The Polar Express" events can be found on the West Virginia Central/Durbin & Greenbrier Valley, which depart from the preserved Western Maryland depot. Here, FP7 #243 awaits departure for the "North Pole." Loyd Lowry photo.

One of the nation's most popular versions of official "The Polar Express" events can be found on the West Virginia Central/Durbin & Greenbrier Valley, which depart from the preserved Western Maryland depot. Here, FP7 #243 awaits departure for the "North Pole." Loyd Lowry photo.Riding The WVC

The WVC's current rail tours today include:

- Cheat Mountain Salamander (departing from either Elkins [8.5-hour trip] or Cheat Bridge [2.5-hour trip], this train operates on select days May through October with a buffet lunch included with both)

- New Tygart Flyer (a 4-hour trip from Elkins hosted on select days from April through October with lunch provided)

- Wild Heart Connector (a package trip from Elkins to Cass which includes an overnight stay and trip aboard the Cass Scenic Railroad)

- Mountain Explorer Dinner Train (offering a full-service dining experience this train runs on select dates from May through September with trips lasting 4 hours)

In addition, consider riding the Cass Scenic Railroad or Durbin Rocket, WVC subsidiary operations which utilize historic geared steam locomotives.

Finally, the Castaway Caboose packages offers guests the chance to stay overnight in restored cabooses while special events like The Polar Express and The Elf Limited are highly popular affairs.

To learn more about all of these experiences please visit the West Virginia Central's website, MountainRailWV.com.

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-37): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 12:57 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-37 Mikes were itsdge steamers to enter service in the late 1920s. Today, all but two survive. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-36): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 11:09 AM

The Rio Grande's K-36 2-8-2s were its last new Mikados purchased for narrow-gauge use. Today, all but one survives. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive.