Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway: Reborn In 1990

Last revised: August 26, 2024

By: Adam Burns

This article is a two-part series covering both the historic Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway (W&LE) and the reborn regional formed in 1990.

The W&LE's early years were a convoluted series of reorganizations, disputes, and lack of financing that resulted in little actual construction taking place. Its modern network would likely have never been built were it not for Jay Gould's financial resources.

During the latter 19th century he worked very hard to complete a coast-to-coast transcontinental railroad. Financial straits ended his efforts but his son, George, continued the endeavor.

Alas, the same fate befell him and the project collapsed. Despite the father's notorious reputation he transformed the W&LE into a modern and profitable carrier.

Coal comprised much of its freight tonnage from originating mines in eastern Ohio while other important traffic included steel and general merchandise.

Until the 1920's passenger service was also brisk although the Great Depression quickly led to its discontinuance. As means of bolstering business the Nickel Plate took control of the W&LE shortly after World War II.

It eventually wound up in the modern Norfolk Southern and was dissolved. A few years afterwards the Class I sold off most of the former W&LE to new owners who resurrected the old name.

In its current form the railroad operates as far west as Toledo and Lima, Ohio and as far east as Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

Photos

Wheeling & Lake Erie GP35 #2666 works the Saginaw Mine via rickety trackage near St. Clairsville, Ohio on October 15, 1991. This customer has since closed its doors. Wade Massie photo.

Wheeling & Lake Erie GP35 #2666 works the Saginaw Mine via rickety trackage near St. Clairsville, Ohio on October 15, 1991. This customer has since closed its doors. Wade Massie photo.History

The Wheeling & Lake Erie's story begins with two different systems; one carrying the same name and another as a narrow-gauge linking Cleveland with Zanesville.

The first W&LE was incorporated on March 10, 1871 as the Wheeling & Lake Erie Rail Road Company. It was the vision of Joel Wood who believed a profitable enterprise lay in the transportation of coal from eastern Ohio mines to Lake Erie ports.

The line was to be standard-gauge (4 feet, 8 1/2 inches) featuring grades no worse than 0.947% (or 50 feet to the mile).

The initial leg would link Wheeling and Sandusky while the ultimate goal was Toledo. Wood's idea was sound but, unfortunately, ill-timed. To attain funding he tried to procure monetary support from major cities along the route.

At first, Wheeling promised $300,000 but a disgruntled taxpayer was successful in having the ordinance rescinded in 1871. Then, the Panic of 1873 nixed any hopes of either Sandusky or Toledo providing assistance.

In the end, Wood's proposal only saw a bit of grading completed (including three tunnels) between Navarre and Martins Ferry (across the Ohio River from Wheeling).

As the W&LE lay mired in uncertainty he was ousted by fellow associates who wanted to scrap the original plans in a favor of a three-foot, narrow-gauge system.

At A Glance

June, 1877 - November, 1949 (Historic) 1990 - Present (Current System) | |

Toledo Division (Toledo - Warrenton, Ohio) Cleveland Division (Cleveland - East Zanesville, Ohio) River Division (Steubenville, Ohio - Wheeling/Benwood, West Virginia) Adena Branch (Adena - Neffs, Ohio) Chagrin Falls Branch (Falls Junction - Chagrin Falls, Ohio) Huron Branch (Norfolk - Huron, Ohio) Minerva Branch (Minerva Junction - Minerva) Massillon Branch (Orrville - Harmon, Ohio) Carrollton Branch (Canton - Carrollton, Ohio) Lorain & West Virginia Railway (Wellington - Lorain, Ohio) | |

These gained widespread popularity after the Denver & Rio Grande successfully demonstrated their viability in the 1870's as a cheaper alternative to their standard-gauge counterparts.

The belief was that such a national network would yield greater returns on investment. This new undertaking began at the northern end when W&LE officials acquired the defunct Milan Canal's tow path.

With a right-of-way ready for rails the first 12.5 miles between Huron and Norwalk opened during June of 1877.

While more grading was completed around New London and to the south (totaling 37 miles), the original W&LE was an utter failure. Before shutting down in late 1879 the group was successful in converting the Huron-Norwalk segment to standard-gauge.

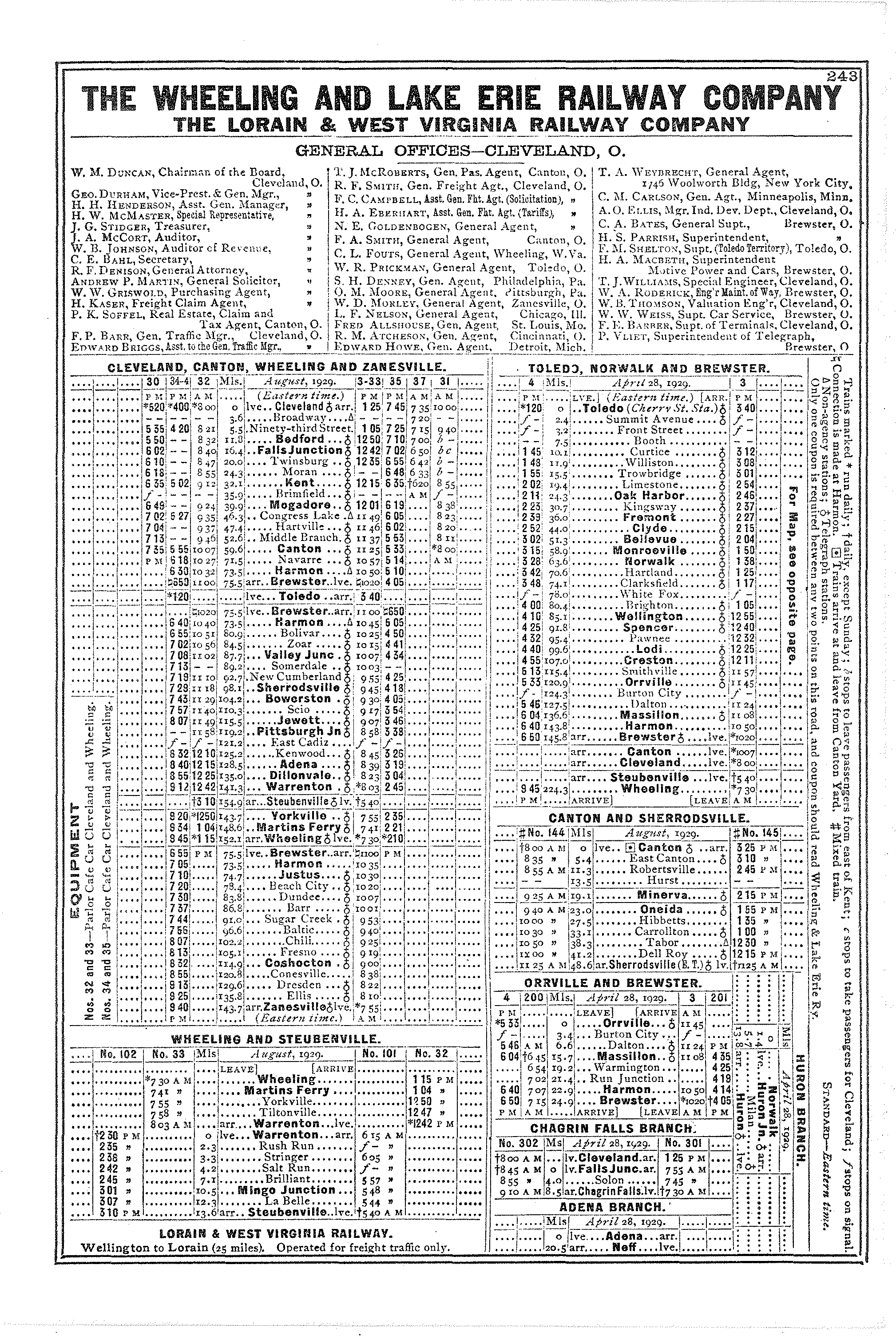

Timetables (1930)

In the meantime, another much more successful three-footer, which went on to become part of the modern W&LE, had been launched nearby. It too, however, got off to a shaky start.

It was promoted by General E.R. Eckley who had similar ambitions to Joel Wood. He incorporated the Ohio & Toledo Rail Road (O&T) on May 7, 1872 to move coal from eastern Ohio mines to Lake Erie.

Instead of building from the Wheeling area, however, this pike would sought a point slightly north at Wellsville, Ohio.

With insufficient capital and an insistence to utilize shoddy construction standards his entire plan may have ended at the drawing board if it were not for the moribund 4-foot, 10-inch Carrollton & Oneida Railroad (C&O).

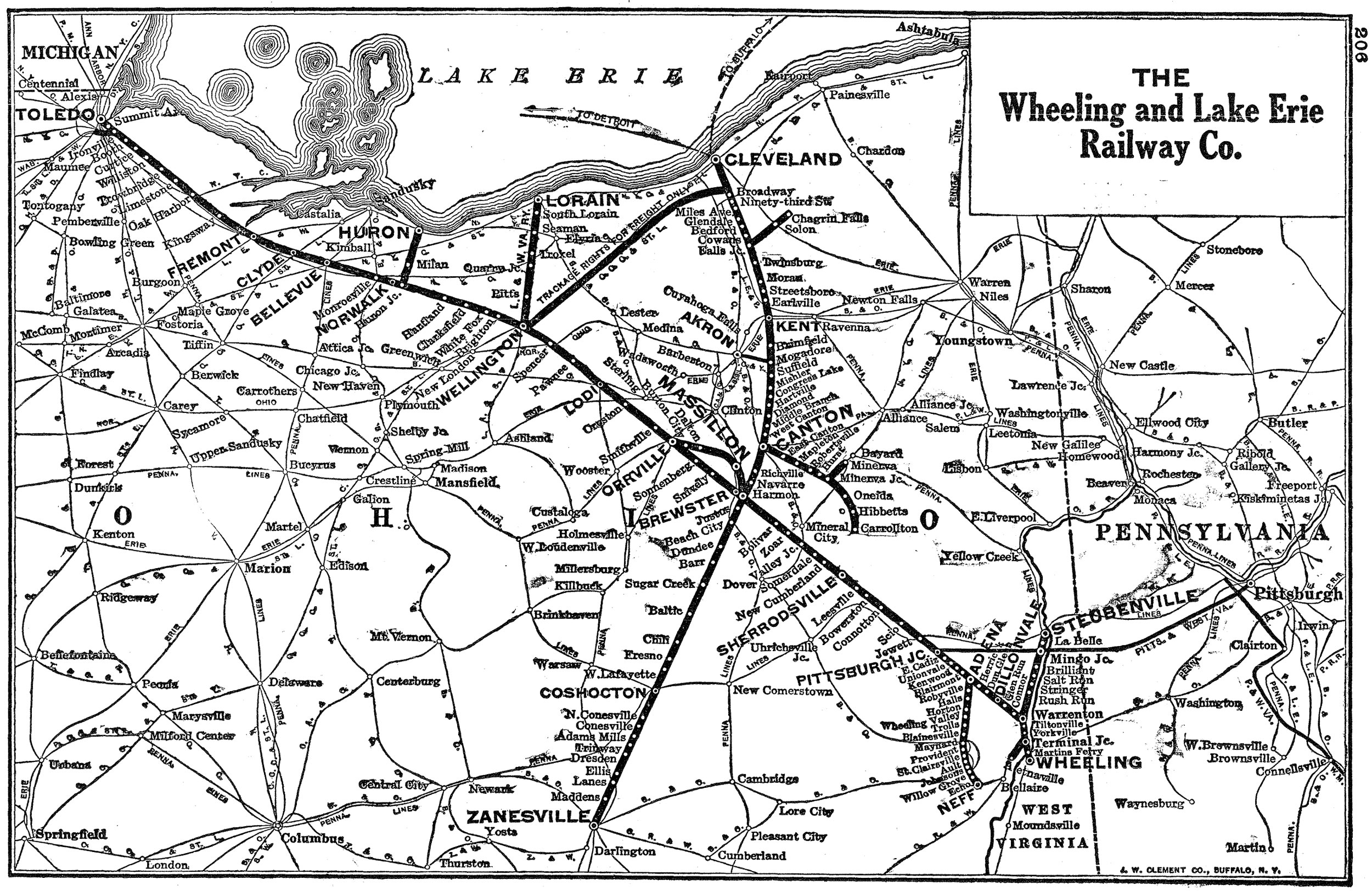

System Map (1940)

Built to even poorer standards than the typical narrow-gauge, the C&O, with a history tracing back to 1837, linked its namesake towns along a 10-mile line laid with strap-iron rail.

At Oneida, it interchanged with the Cleveland & Pittsburgh (a PRR subsidiary). During its brief time in service it was a hopeless failure.

The operation was so bad, in fact, it was returned to its creditors in 1859 and deemed unsafe for steam locomotives.

With no capital it limped along for the next seven years as a local, mule-powered operation. On February 26, 1866 it was reorganized as the Carrollton & Oneida whereupon some capital improvements allowed steam-powered service to return.

Things remained this way until Carrollton sold the railroad to Eckley for $1 on July 15, 1873. He integrated it into his O&T system and made further upgrades, such as laying solid iron T-rail (3-foot gauge) and extending service to Minerva during 1874.

After giving up on a Toledo route the general decided upon a Youngstown connection where interchange could be established with another narrow-gauge, the Painesville & Youngstown.

Following yet another change of heart, Eckley scrapped the Youngstown idea and, instead, would aim for Painesville. Incorporated as the Painesville, Canton & Bridgeport Narrow Gauge Rail Road on January 12, 1875 it began construction from Chagrin Falls.

Without the necessary funding, Eckley managed only to reach Solon (5.15 miles) by November of 1877 before money ran out.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #678 swings onto the former W&LE's Georgetown Branch with empty hoppers at Adena, Ohio, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Nickel Plate Road 2-8-2 #678 swings onto the former W&LE's Georgetown Branch with empty hoppers at Adena, Ohio, circa 1955. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.His venture then passed into Dr. Norman Smith's hands who incorporated the Youngstown & Connotton Valley (Y&CV) on August 29, 1877.

Eckley initially remained president but after a dispute broke out between the two (regarding the northern terminus) the O&T was sold to creditor Cleveland Iron Company.

It then awarded Smith the property in 1878 and Eckley's involvement ended. Just a year later, on October 20, 1879, Smith renamed the company as the Conotton Valley Railroad (CVRR) and completed an extension of the old O&T to Canton in early May of 1880.

His greatest achievement, from an historical perspective, was acquiring solid financial backing for the venture through a Massachusetts syndicate which aimed to develop the CVRR into one of Ohio's most successful narrow-gauges.

To a greater extent they actually accomplished this feat, pouring some $2.6 million into the railroad and completing the entirety of the future Wheeling & Lake Erie's Cleveland - Zanesville corridor.

Upon arriving, they quickly scrapped the Painesville idea and instead sought a direct entry into Cleveland. Construction began on July 5, 1880 and passenger service into downtown Cleveland was inaugurated on February 21, 1882.

Wheeling & Lake Erie GP35 #2660 (built as Southern Railway #2660 in February, 1965) and SD40-3 #3034 (built as Union Pacific SD40 #3034 in April, 1966) layover with other power at the railroad's large terminal in Brewster, Ohio; September, 2005. American-Rails.com collection.

Wheeling & Lake Erie GP35 #2660 (built as Southern Railway #2660 in February, 1965) and SD40-3 #3034 (built as Union Pacific SD40 #3034 in April, 1966) layover with other power at the railroad's large terminal in Brewster, Ohio; September, 2005. American-Rails.com collection.As George Hilton points out in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," while this was ongoing the railroad built a short, 8.7-mile extension south of Carrollton to reach coal mines in the Sherrodsville area that opened on January 1, 1882 (it was later abandoned in 1936).

With a well-built right-of-way now capable of supporting relatively heavy traffic the CVRR next focused on a line due south from Canton.

What was built as the Connotton Valley & Straitsville Railroad would extend to New Straitsville via Zanesville and Coshocton in pursuit of the Perry County coalfields. Work got underway in June of 1882 and had reached Coshocton (114.7 miles) almost exactly one year later in June of 1883.

The group attempted to gather financing for the final push into Zanesville but managed only to secure around $300,000, less than half the amount needed (this money was later used to construct a beautiful, two-story passenger terminal in Cleveland which opened on August 29, 1883).

Despite relatively strong business (in 1884 it carried 456,627 passengers, moved 192,400 tons of coal, and handled 41,668 tons of other freight) the company's heavy debt resulted in receivership during June of 1883.

On May 9, 1885 it was reorganized as the Cleveland & Canton Railroad (C&C) and eventually managed to raise $1.7 million to convert the entire property to standard-gauge, a process completed on November 18, 1888.

The C&C finished the 29-mile line to Zanesville but never made it into Perry County.

Another name change took place in 1892 as the Cleveland, Canton & Southern Railroad (CC&S) but it was again in receivership within a year. The Wheeling & Lake Erie went on to purchase the CC&S for $3.85 million on August 5, 1899.

Modern Network

Gould, arguably the most hated man in America at the time, had big ambitions in which the W&LE would play a vital role. By the 1880's his aspirations for a true, coast-to-coast transcontinental railroad was nearing reality.

The Wabash was the Midwestern component of this network and from its eastern terminus at Toledo offered a potential connection with the W&LE.

The latter's charter stipulated it could build from that point towards the Ohio River in a southeasterly direction. Using the W&LE, Gould would connect it with the New York, Pennsylvania & Ohio (Erie) at Creston for through service into Youngstown.

He then only needed 70 miles of new construction to reach the Pennsylvania-controlled Allegheny Valley Railroad. This system ran across the Keystone State and connected with the Central Railroad of New Jersey, another Gould interest.

During late 1880, he formally acquired the defunct W&LE and by early 1881 things got underway. Actual construction commenced east and west of Creston and by November of 1881 the line was finished from Massillon to Norwalk/Huron.

From the latter point, crews continued west towards Toledo, opening to that city during August of 1882 (following completion of a 1,311-foot bridge over the Maumee River).

Beyond Massillon, the rail-head was extended southeastward towards West Virginia's Northern Panhandle where another prodigious seam of coal was located.

A point known as Valley Junction was reached in August of 1882, which offered interchange with the Cleveland & Marietta Railroad (C&M).

The C&M was also a coal road which served mines in southern Ohio. Its southern terminus was Marietta, the Northwest Territory's first settled community (1788), where interchange was opened with the B&O.

It joined the W&LE in 1882. Unfortunately, Gould's grand plan collapsed in 1883; first, bankruptcy befell the C&M, which separated it from the W&LE.

Then, on July 7, 1884, the W&LE also entered receivership and, for now, the transcontinental scheme was placed on hold. It was reorganized as the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway on June 25, 1886 and immediately began the final push towards Wheeling, West Virginia.

The remaining 43 miles (which required four short tunnels) was finished to Martins Ferry in October of 1889. The last step involved crossing the Ohio River into downtown Wheeling.

By this time both the Baltimore & Ohio and Pennsylvania already served the city from the north (PRR) and south (B&O). The W&LE's entry was via the Wheeling Bridge & Terminal Railway (WB&T), a small belt line serving the area.

At a point slightly north of Martins Ferry known as Terminal Junction, W&LE trains swung onto the WB&T, passed through the town, and then crossed the river just above Wheeling Island.

Its tracks passed over the PRR and Wheeling Creek before following this tributary southward to a connection with B&O at Benwood Yard. Near Jacob Street the W&LE built its own spur off the WB&T that extended 1,300 feet to the south, near Market Street.

Here, it constructed a modest depot not far from the B&O's ornate three-story facility (home to the Wheeling Division's main offices). The W&LE began regular service into Wheeling on February 1, 1892.

Shortly after arriving in the city a 13.6-mile branch was opened to neighboring Steubenville, where an interchange was established with the PRR. By the 19th century's end, the W&LE had transformed itself into a rather robust system.

In 1896, Gould's empire was handed over to his son, George, who continued his father's transcontinental ambitions. The renewed initiative got off to a rocky start when a coal strike hammered traffic, leading to another receivership on January 15, 1897.

This setback was short-lived, however, as business rebounded quickly and the company was reorganized on April 28, 1899.

The W&LE's final noteworthy additions took place during the early 20th century; both were built as subsidiaries, the Adena Railroad (formed on March 5, 1901) and the Lorain & West Virginia Railway (incorporated on January 15, 1906).

The Adena's purpose was to build south from its namesake community to tap more coal seams; the 12-mile extension, completed to Neffs in December of 1905, took considerable time due to the rugged topography.

It required numerous fills and bridges, including a 1,129-foot tunnel near Harrisville. (W&LE's southern lines proved quite rich in black diamonds; during peak years the railroad served 39 mines here capable of producing 23,000 tons daily.)

To the north, the L&WV was built to reach Lorain and the National Tube Company on a 25-mile branch that opened in September of 1907.

Reaching Pittsburgh

With money to spend and a portfolio of railroads which nearly stretched from ocean to ocean, George Gould was closing in on his father's dream by 1900.

His efforts east of Wheeling received a significant boost through the help of Andrew Carnegie. The steel tycoon had an ongoing feud with the Pennsylvania Railroad over freight rates and was desperate for better service at his Pittsburgh mills.

As part of a deal, Carnegie offered Gould and associates a 25% tonnage guarantee. In early 1901 the $20 million "Pittsburgh Extension" was put into motion although almost immediately after this event the original agreement was rescinded when J.P. Morgan acquired Carnegie's steel interests.

The banking mogul, who went on to form the powerful United States Steel Corporation, had no interest in the Carnegie-Gould partnership. However, he did not object to a connection with his Union Railroad.

By that time, Gould controlled the Missouri Pacific, Western Pacific, Denver & Rio Grande Western, Wabash, Western Maryland, and of course, the W&LE.

Once the Pittsburgh Extension was finished he only needed a 50-mile segment from Pittsburgh to Connellsville (later built by the Pittsburgh & West Virginia) to complete the coast-to-coast railroad.

The 63-mile Pittsburgh line was built as the Pittsburgh, Toledo & Western Railroad (PT&W). It left the W&LE at Pittsburgh Junction, crossed a narrow stretch of the West Virginia panhandle, and headed northeasterly into the Steel City.

There, a beautiful terminal station was opened in the downtown Point District. The entire project cost $15.873 million and was engineered to very high standards.

On May 9, 1904 the PT&W, along with a pair of subsidiaries (Cross Creek Railroad chartered in Ohio on April 23, 1900 and the Pittsburgh, Carnegie & Western created on July 17, 1901), were consolidated into the Wabash-Pittsburgh Terminal Railway (W-PT).

According to the article, "Middleman Of The Alphabet Route," by Gus Welty from the November, 1956 issue of Trains Magazine, the W-PT operated its first train from Pittsburgh to the Ohio River on June 1, 1904.

This was the high-water mark for Gould; with numerous projects underway and another financial panic during November of 1907, one-by-one his properties slipped into bankruptcy.

The W-PT entered receivership on May 28, 1908, followed shortly afterwards by the W&LE on June 8th. The two were subsequently separated as the W-PT became the Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railway on January 29, 1917.

The W&LE's reorganization required a great deal of time due to its intricate corporate structure within the Gould empire. It finally exited receivership as the new Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway on December 31, 1916.

The final decades of an independent W&LE (which earned the nickname "Iron Cross" due to the shape of its system map) were quite profitable.

By the 1920s, eastern Ohio enjoyed a robust and humming economy that ranged from steel mills and manufacturing to tire plants and glass producers.

While steel and coal comprised much of W&LE's business it handled a little of everything, particularly in the busy Wheeling area (home to numerous industries).

The railroad's strength could be witnessed during the depression era as Mr. Rehor's book notes it continued profiting more than $1 million annually. After 1920, the road never lost money.

The lean depression years did carry one casualty, passenger service. This business peaked in 1921 only to rapidly evaporate a decade later; by 1933 the railroad earned a minuscule $41,000 from the traveling public.

In his article, "A Half-Century Gone" from the September, 1993 issue of Trains Magazine, author John Corns details the final W&LE passenger, which departed Cleveland for Wheeling (and returned) on July 17, 1938.

The engineer that day, Mr. Frank Eberly, was at the throttle of 4-4-2 #2303. It was a bittersweet moment for many communities as the train was standing-room only on the five-car consist.

The 530-mile W&LE's final years were busy times of 4-8-2's, 2-8-4's and 2-6-6-2's pulling fast freights and heavy drags. On December 1, 1949 the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway was formally leased by the Nickel Plate Road.

Steam Roster (After 1899)

|

Numbers (Original) 1 1 (Lorain & West Virginia) 1 (Zanesville Belt & Terminal) 2 4 (1st), 9-13 3-5 20 21 24-29 30-32 41 42-43 44-48, 51-52 62 63-68 129 141-148 149-153 191-202 203-204 250-264 270 349 800-819 2001-2006 2101-2150 2201-2206 2207-2214 2302, 2306-2330 2307-2310 (2nd) 2401-2420 3573-3580 3951-3980 3981-3986 5101-5105 5106-5125 6001-6020 6401-6432 6801-6810 8001-8002 |

Class A-1 H-9 - A-2 B-1 A-3 G-1 B-2 B-2 B-2 D-1 - D-2 D-3 D-4 G-2 F-1 F-2 H-3 H-4 H-5 G-5 - I-2 E-1 H-6 B-4 B-5 H-7 D-5 H-10 H-7 B-5 B-5 C-1 C-1a M-1 K-1 K-3 I-3 |

Wheel Arrangement 0-4-0 2-8-0 0-6-0 0-4-0 0-6-0 0-4-0 4-6-0 0-6-0 0-6-0 0-6-0 4-4-0 4-4-0 4-4-0 4-4-0 4-4-0 4-6-0 2-6-0 4-6-0 2-8-0 2-8-0 2-8-0 4-6-0 4-4-0 2-6-6-2 4-4-2 2-8-0 0-6-0 0-6-0 2-8-0 4-4-0 2-8-0 2-8-0 0-6-0 0-6-0 0-8-0 0-8-0 2-8-2 2-8-4 4-8-2 2-6-6-2 |

Builder Brooks Brooks Pittsburgh Brooks Brooks Baldwin Brooks Brooks Pittsburgh Baldwin Brooks Taunton Brooks Brooks Baldwin Brooks Brooks Brooks Pittsburgh Alco/Pittsburgh Baldwin Brooks Baldwin Brooks Brooks Brooks Rogers Rhode Island Baldwin Baldwin Alco Brooks W&LE Alco Alco/Pittsburgh W&LE Brooks Alco Roanoke/N&W Baldwin |

Date Built/Notes 6/1891 12/1910 1882 6/1893 11/1888 - 6/1893 5/1903 - 6/1903 8/1892 6/1891 2/1901 - 1/1902 6/1903 1/1890 12/1866 - 8/1867 2/1887 - 6/1891 4/1889 6/1903 6/1893 11/1888 - 4/1889 6/1891 - 6/1893 2/1900 - 1/1902 2/1902 5/1903 2/1899 7/1890 4/1917 - 5/1917 4/1905 3/1905 - 4/1905 4/1905 9/1906 - 10/1906 10/1906 - 12/1906 2/1910 - 3/1910 7/1913 1/1901 - 10/1902 1929 - 1940 6/1944 11/1918 1928-1930 8/1918 - 10/1918 4/1937 - 9/1942 6/1926 - 10/1926 9/1919 |

Please note that the listing of second numberings presented here is for reference only. The original W&LE steam roster dates back to 1877 and includes locomotives with many of the same numbers.

Diesel Roster

| Builder | Model | Road Number | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | NW2 | D-1 | 4/1940 |

| EMD | NW2 | D-2 | 8/1940 |

| EMD | NW2 | D-3 | 6/1941 |

| EMD | NW2 | D-4 | 8/1941 |

These four NW2's were the only diesels the W&LE ever owned. They went on to become Nickel Plate #95-98.

Wabash-Pittsburgh Terminal Railway Roster

|

Numbers (Original) 1 2-3 4 5-6 330-331 900-901 910-919 2001-2006 2101-2150 2201-2206 |

Class G-1 H-1 B-2 G-2 D-5 H-7a H-8 E-1 H-6 B-4 |

Wheel Arrangement 4-6-0 2-8-0 0-6-0 4-6-0 4-4-0 2-8-0 2-8-0 4-4-2 2-8-0 0-6-0 |

Builder Alco Altoona/PRR Baldwin Pittsburgh McKees Rocks Brooks Brooks Brooks Brooks Rogers |

Date Built/Notes - 1881-1882 10/1888 8/1890 9/1896 4/1909 4/1909 4/1905 3/1905 - 4/1905 4/1905 |

Current Roster

| Builder | Model | Road Number(s) | Date Built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | GP35 | 100 (2nd) | 1965 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | GP35 | 101 (2nd) | 1964 | Ex-Norfolk & Western |

| EMD | GP35 | 102-103 (2nd) | 1965 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | GP38 | 100-103 (1st) | 1967 | Ex-B&O (Leased From VMV) |

| EMD | GP35 | 104 | 1965 | Ex-Southern/Savannah & Atlanta |

| EMD | GP35 | 105-107 | 1965 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | GP35 | 108-110 | 1964 | Ex-Southern/Savannah & Atlanta |

| EMD | GP35 | 111 | 1965 | Ex-Rio Grande |

| EMD | GP35 | 112 | 1965 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | GP35 | 200 | 1964 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | SW1200 | 1203 | 1957 | Ex-Wabash |

| EMD | SW1500 | 1501-1502 | 1966 | Ex-Indianapolis Union #23-24* |

| EMD | GP35 | 2645, 2650-2653, 2655, 2660-2662, 2664, 2679, 2691, 2695, 2699 | 1965 | Ex-Southern |

| EMD | GP35 | 2703 | 1965 | Ex-Southern (EMD Trucks) |

| EMD | GP35 | 2705-2709, 2713 | 1965-1966 | Ex-Southern/Savannah & Atlanta |

| EMD | SD40 | 3016, 3034 | 1966 | Ex-Union Pacific |

| EMD | GP35 | 3045 | 1965 | Ex-Rio Grande |

| EMD | SD40X | 3046 | 1966 | Ex-Union Pacific |

| EMD | SD40 | 3048-3049, 3067-3068, 3073, 3102, 4001, 4003, 4016, 4018, 4025 | 1966-1971 | Ex-Union Pacific |

| EMD | GP40 | 300-305 | 1965-1971 | Ex-PC, Ex-NYC, Ex-D&RGW |

| EMD | SD40-2 | 758, 6310-6316, 6347-6348, 6351-6354, 6381-6389, 7355, 7375, 7377 | 1973-1986 | Ex-British Columbia Railway, Ex-MILW, Ex-MP, Ex-TFM, Ex-BN/C&S |

| EMD | SD45 | 1765-1770, 1784, 1800 | 1970 | Ex-N&W |

| EMD | SD45 | 6981 | 1969 | Ex-C&NW |

| EMD | SD40-3 | 3016, 3034 | 1966 | Ex-UP SD40s |

| EMD | SD40X | 3046 | 1965 | EMD Demonstrator |

| EMD | SD40 | 3048-3049, 3068, 3073, 3102, 4001, 4003, 4016, 4018, 4025, 6349-6350 | 1966-1971 | Ex-UP, Ex-MP, Ex-KCS |

| EMD | GP9R | 4602 | 1957 | Ex-CV GP9 |

| EMD | SD40T-2 | 5391, 5413 | 1978-1980 | Ex-D&RGW |

* IU #23 was built as Electro-Motive demonstrator #107 in June of 1966.

* All GP35's, except #2703 and #3045, featured AAR Type B trucks from trade-in Alco RS units.

Wheeling & Lake Erie 2-8-4 #6415, a Class K-1 "Berkshire" out-shopped by Alco in 1939, works freight service through rural Ohio circa 1950. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Wheeling & Lake Erie 2-8-4 #6415, a Class K-1 "Berkshire" out-shopped by Alco in 1939, works freight service through rural Ohio circa 1950. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Operations Today

The modern incarnation of the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway began in 1990 when Norfolk Southern sold off 800 miles of superfluous trackage in the Midwest.

Today's W&LE operates much of the original network (NS retained the Bellevue to Toledo section but provides trackage rights over this stretch) along with former lines of:

- Pittsburgh & West Virginia

- Akron, Canton & Youngstown (114 miles between Mogadore and Carey)

- Two small segments of the B&O picked up from CSX (between North Canton and Sandyville as well as an Ohio River crossing to to reach B&O's old Benwood terminal)

The company's early years were fraught with uncertainty and heavy debt. In his July, 2001 article entitled, "Starting Small, Thinking Big," author Craig Sanders details these struggles as the company was saddled with the $42 million it owed NS.

A new management team was brought in during 1991 and after nearly a decade of hard work they had finally turned things around.

Today the W&LE is as strong as ever, with a traffic base in coal, iron ore, steel, aggregates, plastics, chemicals, forest products, and even grain. The Conrail breakup has also allowed it to dabble into the profitable intermodal business.

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive. -

Rio Grande K-27 "Mudhens" (2-8-2): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 05:40 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-27 of 2-8-2s were more commonly referred to as Mudhens by crews. They were the first to enter service and today two survive. -

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved.