Virginian Railway: Map, Rosters, History, Electrification

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Virginian Railway was one of the last great systems built in this country. The vision of oil tycoon Henry Rogers and engineer William Page it had but a single purpose, hauling coal.

Constructed to extremely high-standards its main line was less than 500 miles but a constant irritation to the much larger Norfolk & Western.

Despite its small size the Virginian operated with precision-like efficiency handling black diamonds from tipple to tidewater.

Formed at the turn of the 20th century it opened within a few years thanks to Mr. Rogers' deep pockets. During the 1920's a section of main line west of Roanoke, Virginia was electrified and the railroad truly shined.

At first, boxcabs were utilized and then later much more powerful rectifiers from General Electric arrived.

Vexed to the point of frustration the N&W paid a premium to eliminate its longtime competitor, acquiring the road during the late 1950's. Today, much of the Virginian's main line remains in use under successor Norfolk Southern.

Photos

Virginian Railway boxcab #113 (Class EL-1a) sits quietly under the wires at Princeton, West Virginia circa 1957. These units typically worked in groups of three. Richard Cook photo.

Virginian Railway boxcab #113 (Class EL-1a) sits quietly under the wires at Princeton, West Virginia circa 1957. These units typically worked in groups of three. Richard Cook photo.History

The history of the Virginian Railway does not carry a fascinating backstory of business failings, reorganizations, name changes, and financial shortfalls.

It was simply planned, engineered, built, and opened all thanks to the financial backing of Henry Huttleston Rogers. Mr. Rogers earned his millions in the oil industry where he first became involved during the 1860's with Charles Pratt.

Shortly afterwards he invented a way to separate naphtha from crude oil, making oil refining possible. During the mid-1870's Rogers and Pratt partnered with John Rockefeller's Standard Oil and great success ensued.

At A Glance

Sewall's Point/Norfolk, Virginia - Suffolk - Roanoke - Princeton, West Virginia - Elmore - Deepwater, West Virginia Elmore - Gilbert/Glen Rogers Mullens - Beckley - Cranberry Pax - Tamroy/Glen Jean Oak Hill Junction - Oak Hill/Carlisle/Lochgelly | |

He held a prominent position within the company and later branched out into the copper and steel industries before finding his way into railroads through prominent tycoon Edward Henry Harriman. At this point he became interested in a number of projects ongoing in West Virginia.

The first was the Ohio River Rail Road, a small system that opened between Wheeling and Huntington/Kenova in 1888.

It skirted the eastern bank of the Ohio River and was funded primarily through Standard Oil. The railroad was later leased by the Baltimore & Ohio in 1901 and purchased outright in 1912.

Virginian Railway 4-6-2 #214 (Class PA) has train #3 departing Norfolk, Virginia at Carolina Junction (South Norfolk) crossing the Norfolk Southern on an October morning in 1954. H. Reid photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Virginian Railway 4-6-2 #214 (Class PA) has train #3 departing Norfolk, Virginia at Carolina Junction (South Norfolk) crossing the Norfolk Southern on an October morning in 1954. H. Reid photo. American-Rails.com collection.Next, he eyed the Mountain State's southern coal fields where he met William Page who was attempting to build the Deepwater Railway (incorporated in 1898). This is where the Virginian's story begins. Page was an accomplished engineer but was having trouble getting his dream off the ground.

He wished to open a road running from the Kanawha River that would head south to tap rich coal reserves before striking out eastward for the Virginia border.

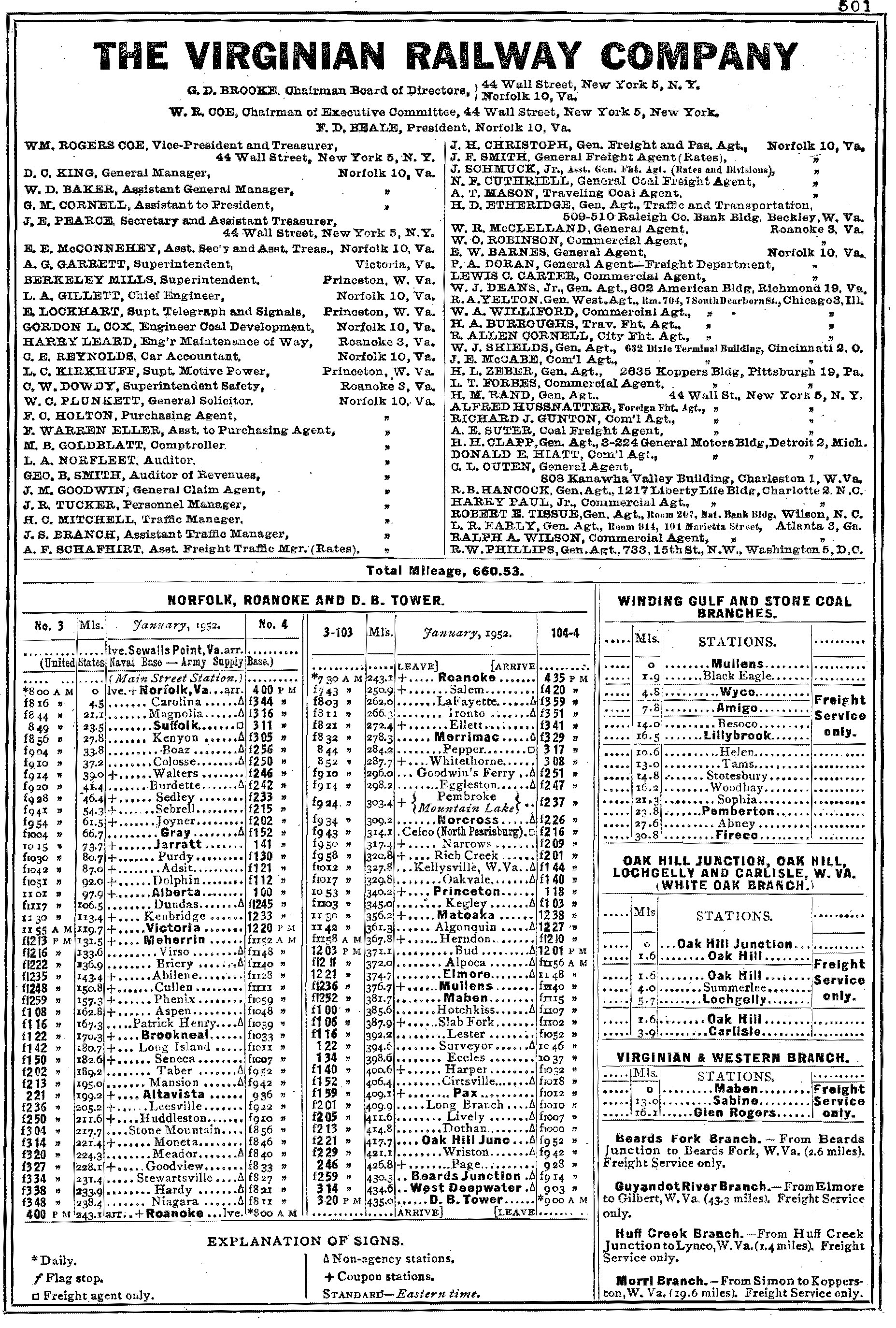

Timetables (1952)

However, the much larger, more powerful, and entrenched Norfolk & Western and Chesapeake & Ohio were thwarting these efforts by refusing the little short line favorable interchange rates.

Once Rogers became involved in 1902 everything changed. Money was not a problem as the industrialist pumped $50 million of his own money into the project. Many railroads were designed with the intention of connecting two or more noteworthy cities but not the Virginian. Its sole purpose was to move coal.

According to H.A. McBride's article, "Coal Carrier" from the January, 1950 issue of Trains Magazine, at the time the Deepwater Railway was only 4 miles in length running between Deepwater and Robson.

Logos

The Virginian Railway logo, often found on the long hood of the company's Fairbanks-Morse diesels. Author's work.

The Virginian Railway logo, often found on the long hood of the company's Fairbanks-Morse diesels. Author's work.Expansion

Following Rogers' involvement the project took off; building southward from Deepwater it wound its way along small tributaries like the Little Righthand Fork, Loop Creek, and Slab Fork before reaching Mullens/Elmore.

This stretch contained virtually all of the Virginian's rich coal seams with branches snaking their to such remote areas as Glen Rogers, Gilbert, Lochgelly, and Willibet. The branch running northeastward from Mullens served the railroad's largest city in West Virginia at Beckley which during the late 1940's contained more than 10,000 residents.

Heading southeasterly the route followed more small waterways before entering the Bluestone River valley and finally Princeton. This town was later home to an important yard. The ultimate destination was the Hampton Roads ports at Norfolk/Newport News.

To build into Virginia required the formation of a new company and the Tidewater Railway was established in 1904 for this purpose. The Deepwater Railway contained rugged but respectable grades while the Tidewater project proved much easier.

It headed eastward through Virginia's western mountains, crossed the Piedmont's rolling hills, and finally terminated in the coastal plains. While construction was ongoing the Tidewater and Deepwater systems were merged into the new Virginian Railway during March of 1907.

Like the N&W, Roanoke became an important location. It was reached in 1906 and already growing thanks to the Norfolk & Western.

Here, a major terminal was established along the north bank of the Roanoke River. The city was also the terminus of its Western Division (Roanoke - Deepwater) and Eastern Division (Roanoke - Norfolk) in addition to being the eastern-most point of its electrification.

As construction continued the main line was opened from Deepwater to Norfolk in April of 1909. Engineered to extremely high standards, as Mr. McBride notes, trains literally traveled down hill from West Virginia all of the way into Norfolk leaving empties to make the climb back to the mines.

The worst grade along the entire 422-mile main line was between Mullens and Matoaka at 2.07%. Just nine miles away from Norfolk two coal piers were constructed at "Sewalls Point" (today, commonly spelled Sewell's Point) to handle export coal shipments.

These structures were more than 1,000 feet in length and, combined, could empty 23 loaded trains each day equating to roughly 232,000 tons.

A massive Virginian 2-6-6-6 (AG), #903, is seen here on display at the National Railway Historical Society's convention in Roanoke, Virginia during the summer of 1957. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A massive Virginian 2-6-6-6 (AG), #903, is seen here on display at the National Railway Historical Society's convention in Roanoke, Virginia during the summer of 1957. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger service launched in May between Roanoke and Deepwater with trains running the railroad's entirety by July 1st.

They were modest affairs but continued to offer parlors, diners, and Pullman's until August of 1932 when unnamed #3 and #4 became coach-only consists. Years later a single baggage and coach (rented from the N&W) did the honors.

As H. Reid's article, "Of Black Upholstery And Commanding Exhaust" from the August, 1956 issue of Trains Magazine points out the final runs occurred on January 29, 1956.

They witnessed a flurry of nostalgic patrons, helped by railfans belonging to the local Tidewater Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society.

The additional interest required the need for an extra coach. But coal, of course, always paid the bills; roughly 17.5 million tons of freight was handled in 1948 and black diamonds comprised 88%.

A big Virginian Railway 2-6-6-6, #902 (Class AG), appears to be headed west over the Elizabeth River in Norfolk, Virginia with a string of empties in December, 1954. Author's collection.

A big Virginian Railway 2-6-6-6, #902 (Class AG), appears to be headed west over the Elizabeth River in Norfolk, Virginia with a string of empties in December, 1954. Author's collection.Until 1931 it had relied on a single connection at Deepwater with rival Chesapeake & Ohio. That year it completed a bridge across the Kanawha River which provided for a much more receptive interchange with the New York Central.

This transformed the Virginian from simply a coal road to a prominent player in the Midwestern gateway enabling the introduction of time freights.

No longer did the N&W and C&O have exclusive rights in this regard. The bridge also slightly improved passenger services by allowing trains to reach Charleston's Smith Street Union Station which was also served by the Baltimore & Ohio and NYC.

Virginian Railway 2-8-2 #462 (Class MC) carries out switching chores at the yard in Norfolk, Virginia during December of 1954. Photographer unknown. Author's collection.

Virginian Railway 2-8-2 #462 (Class MC) carries out switching chores at the yard in Norfolk, Virginia during December of 1954. Photographer unknown. Author's collection.Including all coal branches the Virginian maintained a network of 623 route miles. Its main line was laid with heavy, 131-pound rail to handle daily coal drags which sometimes reached 17,000 tons and more than a mile in length (normal consists included about 10,000 tons).

It even employed massive 100-ton hoppers decades before they saw widespread use. All of these efforts were aimed at improving efficiency, dropping the operating ratio, and generally making more money.

Perhaps the most visible attempt at this was the electrification project launched after World War I. In 1923 it contracted with Westinghouse to electrify 134 miles between Roanoke and Mullens.

It required three years to complete at a cost of $15 million. Mullens was just a small community tucked away deep within the coal country of Wyoming County, situated along the confluence of the Slab Fork and Guyandotte River. Here, the railroad constructed a moderate engine facility and small yard to maintain its fleet of electrics.

Electrification

The Virginian's electrification constituted the longest stretch of mountainous electrification in the eastern United States. The project began in 1922 and was completed three years later at a cost of $15 million.

The railroad energized a total of 134 main-line miles from Mullens, West Virginia to Roanoke, Virginia. By this time, high-voltage single-phase alternating current (AC) transmission had become the preferred means of electrifying rail lines.

AC transmission has none of the inherent drawbacks of direct-current (DC), requiring relatively cheaper overhead wires (catenary) that could employ thousands of additional volts.

The Virginian employed an 11,000 volt (AC) system supplied by its own power plant at Narrows, Virginia. Its first batch of locomotives were products of Alco and Westinghouse, boxcabs with a 1-D-d wheel arrangement which arrived in April of 1925. While rather simple in appearance these locomotives could provide tremendous power as noted below.

Virginian 4-6-2 #212 on display at the NRHS convention in Roanoke, Virginia during the summer of 1957. The railroad rostered a small fleet of six for its modest passenger services, #210-215, manufactured by Alco's Richmond Works in 1920. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Virginian 4-6-2 #212 on display at the NRHS convention in Roanoke, Virginia during the summer of 1957. The railroad rostered a small fleet of six for its modest passenger services, #210-215, manufactured by Alco's Richmond Works in 1920. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.The railroad designated them as EL-3a, EL-2a, and EL-1a although their only difference was the number of units operating together (i.e., EL-3a's operated in threes, EL-2a's in twos, and EL1-a's as a single unit).

Most often they operated in sets of three as class EL-3a and could produce an impressive 6,000 horsepower and 231,000 pounds of tractive effort.

The latter was in part due to their large size, weighing in at over 1.2 million pounds with a length of 152 feet and 3 inches. In all, the Virginian owned 16 of these early boxcabs; ten of the EL3a class numbered 100-109 and six of the EL-1a class numbered 110-115. The lone EL2-a, numbered 100, was later reclassified as an EL-3a.

The Virginian’s boxcabs used the early side-rod design in transferring power to the driving wheels. The locomotives used what were called "phase converters" to turn single-phase AC transmission into three-phase for use by its large induction motors. They remained the sole motors until the late 1940's when new units began arriving.

To supplement its aging boxcabs, which were reliable and effective but hard on the track, Virginian turned to General Electric. Its first purchase came in 1948 when it took delivery of four units known as AC rectifiers.

This technology was truly exceptional for its time enabling the inherent advantages of AC, which was then converted to high-adhesion DC. According to the book, "Electric Railways: 1880-1990" by Michael Duffy, rectifiers provided the following advantages:

"Performance was independent of supply frequency. Weight was about 15% less than when supplied with 15 Hz...compared with a single phase locomotive supplied with 16.66 Hz and using commutator motors.

The railway supply could be drawn from the grid at industrial frequency. Motor control was complete and loss free.

The single-phase AC/DC type of locomotive was simple in construction. The rectifier was fed by the transformer and the motors were in series with a smoothing choke and received DC voltage varying between zero and the maximum. Reduction in motor weight was an advantage.

The single-phase commutator motor was restricted to low frequencies in railway service, and was large and heavy. The DC motor was smaller and lighter.

The overhead equipment carrying the single-phase contact wire was lighter than the equipment needed to carry an equivalent DC supply. The rectifier locomotive combined the most advantageous form of fixed works with the favoured traction motor."

The Virginian's new semi-permanently coupled units were numbered 125-128 and classified as EL-2b. Sporting an attractive, streamlined cab design they featured a B-B+B-B + B-B+B-B wheel arrangement, rated at 50 mph, capable of producing 6,800 horsepower, and 260,000 pounds of tractive effort.

Eight years after their arrival even more new power arrived, twelve Ignitron rectifiers (also from GE) designated class EL-C. They featured the now-classic diesel road-switcher design and could produce 3,300 horsepower while delivering 98,500 pounds of tractive effort.

As a side note, the EL-Cs had a very interesting history. They lasted a mere year under Virginian's ownership before N&W acquired the road.

After ending its electrification (and pulling up one of its two main lines) the N&W sold the EL-C's to New Haven. They were subsequently reclassified as EF-4 before the New Haven itself disappeared into Penn Central in 1969.

Yet another reclassification followed as E-33's. After Penn Central's collapse the units found their way into Conrail which began on April 1, 1976.

The few that remained continued to carry the E-33 designation until electrified freight service ended in the early 1980's. Today one survives, #135, residing at the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke.

The Virginian utilized an efficient, 11,000-volt, alternating current (AC) system with powered supplied by its own power plant at Narrows, Virginia. Its first batch of locomotives were products of Alco and Westinghouse, delivered in April of 1925.

According to the June, 1925 issue of "Railway & Locomotive Engineering," the three-unit boxcab sets could produce more than twice the starting tractive effort of Virginian's largest steamers (231,000 pounds) and maintain a continuous rating of 135,000 pounds.

In addition, they offered an impressive 6,000 horsepower (continuous). In 1948 they were supplemented with even more powerful streamlined rectifier designs from General Electric.

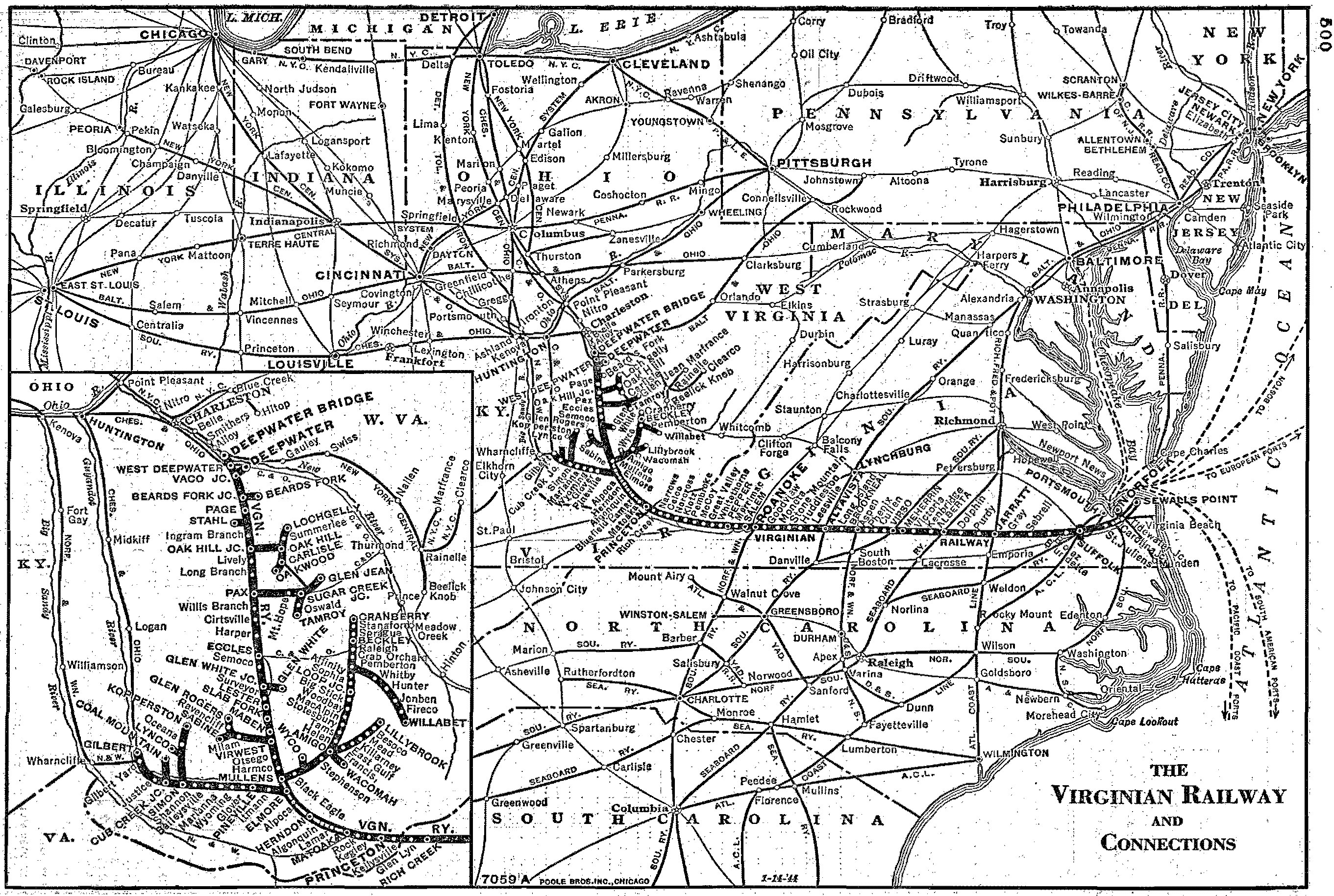

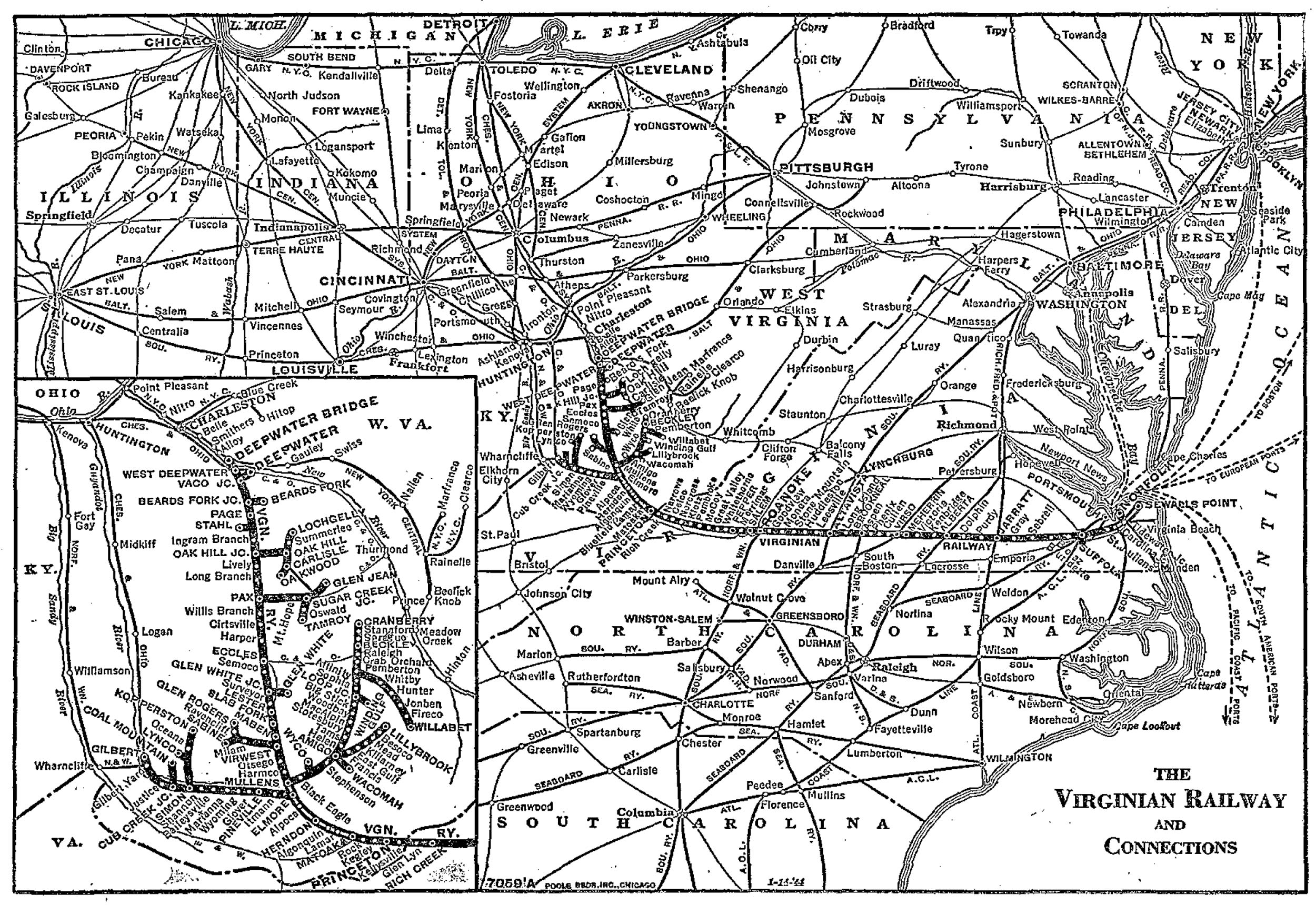

System Map (1944)

Seven years later more new power joined the fleet in 1955, a dozen Ignitron rectifiers (also from GE) designated class EL-C. Even more contemporary than the EL-2b's they featured the now-classic diesel road-switcher look with a C-C wheel arrangement. The EL-C's were rated at 3,300 horsepower and delivered 98,500 pounds of tractive effort.

Make no mistake, while the big electrics were often the most celebrated very large steamers were also utilized in drag assignments. These articulateds including huge arrangements like 2-6-6-6's, 2-8-8-0's, 2-8-8-2's, and behemoth 2-10-10-2's. It once even experimented with the gigantic 2-8-8-8-4 "Triplex," a 1916 product of Baldwin.

Diesel Roster

Fairbanks-Morse

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H16-44 | 10-49 | 1954-1957 | 40 |

| H24-66 (Train Master) | 50-74 | 1954-1957 | 25 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 6 | 1941 | 1 |

Electric Roster (As Of 1950)

| Class | Wheel Arrangement | Road Number(s) | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL-3a | 1-D-1 (Set of 3) | 100-111 | Westinghouse/Alco | 1925/1926 |

| EL-2b | B-B+B-B + B-B+B-B | 125-128 | General Electric | 1948 |

| EL-C | C-C | 130-141 | General Electric | 1955 |

Steam Roster (All-Time)

| Class | Wheel Arrangement | Road Number(s) | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 0-8-0 | 2, 4 | Alco/Baldwin | 1909-1910 |

| PA | 4-6-2 | 210-215 | Alco | 1920 |

| EA | 4-4-0 | 295 | Baldwin | 1906 |

| MD | 2-8-2 | 410 | Baldwin | 1921 |

| MB | 2-8-2 | 420-460 | Baldwin | 1909-1910 |

| MC | 2-8-2 | 462-479 | Baldwin | 1912 |

| MCA | 2-8-2 | 480-484 | Baldwin | 1912 |

| BA | 2-8-4 | 505-509 | Lima | 1946 |

| AF | 2-8-8-0 | 610 | Baldwin | 1921 |

| XA | 2-8-8-8-4 | 700 | Baldwin | 1916 |

| US | 2-8-8-2 | 701-735 | Alco | 1919-1923 |

| USE | 2-8-8-2 | 736-742 | Alco | 1919 |

| AE | 2-10-10-2 | 800-809 | Alco | 1918 |

| AG | 2-6-6-6 | 900-907 | Lima | 1945 |

Norfolk Southern's Virginian heritage locomotive, SD70ACe #1069, heads east on freight 162 between Salisbury and Statesville, North Carolina on October 20, 2012. This yellow and black scheme was the original livery worn by Virginian locomotives. Dan Robie photo.

Norfolk Southern's Virginian heritage locomotive, SD70ACe #1069, heads east on freight 162 between Salisbury and Statesville, North Carolina on October 20, 2012. This yellow and black scheme was the original livery worn by Virginian locomotives. Dan Robie photo.Other standard designs like the 4-6-2 performed passenger duties and fast 2-8-4 Berkshires worked the fast time freights through Virginia.

Into the diesel era the Virginian stuck solely with Fairbanks-Morse purchasing its H16-44 and H24-66 road-switchers during the mid-1950's. FM's opposed-piston designs were not well-liked on many roads but the Virginian was different, owning a fleet of 65 units.

Norfolk & Western Acquisition

For 50 years the railroad made a very profitable living hauling bituminous coal from tipple to tidewater. In an interesting historical footnote it is credited with kicking off the modern mega-merger movement when the Norfolk & Western came calling in the late 1950's hoping to finally eliminate its longtime rival.

After the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the deal the Virginian Railway formally disappeared in 1959. Just three years later N&W shutdown its electrification on June 30, 1962.

Today, most of its superb main line continues to play an important role under Norfolk Southern while SD70ACe #1069 honors its corporate heritage sporting the road's classic yellow and black livery.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive. -

Rio Grande K-27 "Mudhens" (2-8-2): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 05:40 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-27 of 2-8-2s were more commonly referred to as Mudhens by crews. They were the first to enter service and today two survive. -

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved.