United States Railroad Administration (USRA)

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The United States Railroad Administration (USRA) was not exclusive to World War I. During the 1970's the similarly named United States Railway Administration (operating under the auspices of the Department of Transportation) was formed to create what became the Consolidated Rail Corporation.

Better known as Conrail, this federally created railroad was tasked with saving the northeast's bankrupt systems, notably Penn Central. The best remembered version of the USRA was that formed during the 'Great War,' which effectively nationalized the railroads.

In many ways, the U.S. government was responsible for the gridlock due to recently passed legislation which prevented railroads from raising freight rates.

Whatever the case, the USRA's few years of existence produced both pros and cons. The agency was heavily criticized for its treatment of equipment, infrastructure, and general accounting whereby profits were ignored.

Despite its problems it also set forth standardized practices which forever aided the industry, and helped prevent another federal takeover during World War II. The information here offers a brief history of the USRA.

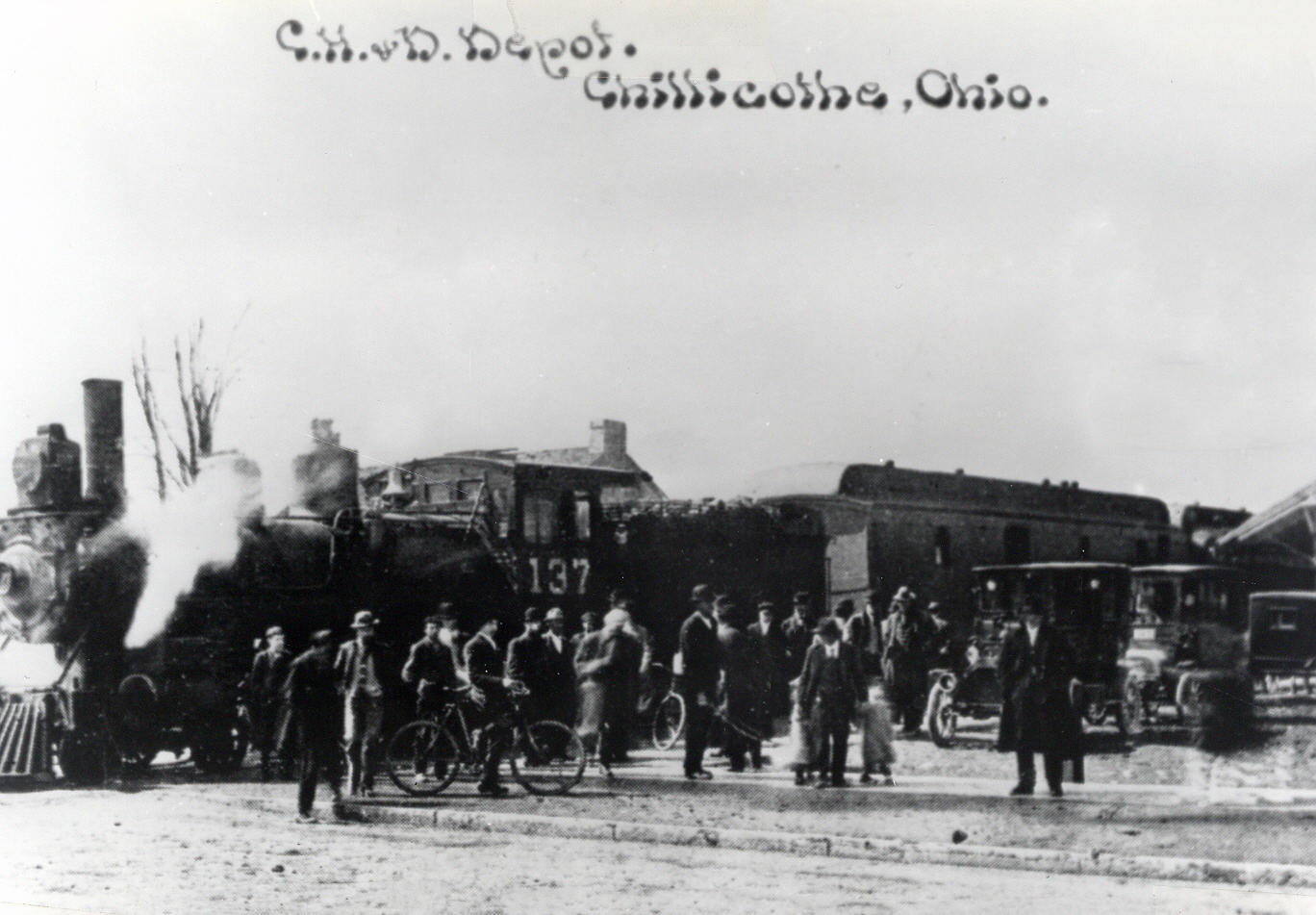

A view of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad in Chillicothe, Ohio, circa 1920. Author's collection.

A view of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad in Chillicothe, Ohio, circa 1920. Author's collection.History

Regulation set into motion the transportation calamity which befell the nation during World War I. While the government held its share of the blame, railroads were just as guilty for their arrogant, "public be damned" attitude.

It began in 1887 with the Interstate Commerce Commission's creation which, for the first time, brought federal oversight to the industry.

Initially, the ICC held little actual power but that soon changed, particularly through a series of acts passed after 1900; the Elkins Act of 1903 ended the use of rebates to protect competition and fair pricing and the Hepburn Act of 1906 expanded upon its predecessor providing the ICC primary authority in freight rate adjustments.

In short, railroads could not amend such without the agency's approval. Finally, the Mann-Elkins Act of 1910 further increased the ICC's power by forcing railroads to show just cause for any rate hike.

The timing of these acts was particularly bad. In mid-summer, 1914 World War I broke out across Europe and the United States subsequently sent millions of dollars in supplies to its allies. Then, America itself entered the conflict on April 6, 1917.

Purpose

Between 1900 and the war's outbreak, railroads endured rising operating expenses as costs outpaced general inflation. However, with the ICC now controlling rates, they could not freely raise them.

Every attempt was denied although he agency would eventually allow for a small 5% increase, which failed to improve the situation.

As a result, historian John Stover notes in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," by 1915 over 40,000 miles of railroads were in default or receivership which included the Wabash; Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific; New York, New Haven & Hartford; and the St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad (Frisco).

Statistics

25% (South and West) 40% (East) | |

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- DeNevi, Don. America's Fighting Railroads, A World War II Pictorial History. Missoula: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1996.

- Hilton, George and Due, John. Electric Interurban Railways in America, The. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

At the time, there was a total of $17.5 billion invested in the national network, of which roughly half was funded debt. As the industry struggled, a major strike broke out among the leading crew unions in 1916 (engineers, firemen, conductors, and trainmen). They sought a reduction in the workday from ten to eight hours.

With companies unwilling to budge, Congress and President Woodrow Wilson intervened to pass the Adamson Act, which essentially gave in to union demands.

A view of St. Marys, West Virginia, probably during the 1940s. The small town was served by the Baltimore & Ohio. Author's collection.

A view of St. Marys, West Virginia, probably during the 1940s. The small town was served by the Baltimore & Ohio. Author's collection.Not surprisingly, railroads sued but the legislation was upheld by the United States Supreme Court in 1917. The next domino to fall was a major car shortage. The issue had been building for months as traffic bound for European allies predominantly traveled from west to east.

These countries would ultimately order some $3 billion of munitions from the United States. With such an uneven traffic flow, cars stacked up in east coast ports awaiting shipment, essentially acting as rolling warehouses.

The problem was further compounded by the U.S. government, which stipulated high-priority shipments deemed essential to the war effort take precedence over general movements.

By November, 1917 the issue caused the shortage to reach some 158,000 cars. Unfortunately, railroads had partially caused this issue themselves due to a lack of standardized practices, inhibiting their ability to operate an efficient national network, particularly as their importance to the national economy had grown immensely.

In 1880 there were roughly 93,000 miles in service, carrying operating revenues of $614 million with a total investment of $5 billion and 419,000 workers. By 1916, mileage had jumped to the record which still stands, 254,037, with operating revenues of $3.353 billion.

In addition, investment and total employees had ballooned to $21 billion and 1.701 million respectively.

The industry attempted to correct the logistical issue themselves, under an initiative launched by Baltimore & Ohio president Daniel Willard who, as a member of the Advisory Commission of the Council of National Defense, suggested railroads be operated as a single system.

It was similar to what the USRA ultimately did but would have been privately operated. Unfortunately, the idea ran up against 1890's Anti-Trust Act. As railroads continued to struggle, President Wilson felt he had no choice but to take the unprecedented step of nationalizing the industry.

Naturally, the idea drew scorn and resentment from managers who balked at the concept. Nevertheless, the new United States Railroad Administration went into effect on December 28, 1917.

Historian Jim Boyd points out in his book, "The American Freight Train," the industry was technically rented and not nationalized with each railroad paid the average net operating income from 1914 through 1917.

While true, with little choice in the matter, the term nationalization is applicable. Interestingly, even some interurbans which handled a great deal of freight, were taken over.

An aerial view of Chillicothe, Ohio, probably during the 1940s. The town sat along the Baltimore & Ohio's main line to St. Louis. Author's collection.

An aerial view of Chillicothe, Ohio, probably during the 1940s. The town sat along the Baltimore & Ohio's main line to St. Louis. Author's collection.Led by William G. McAdoo, Secretary of the Treasury (and President Wilson's son-in-law), who also had worked in the railroad industry, the USRA's primary purpose was to operate the 254,000+ mile network as a single entity.

To do this, McAdoo believed standardization was needed to achieve greater efficiencies and operational improvements.

Up until that time, there had been few, largely due to fierce competition and monopolistic attitudes. Since the industry's earliest days many promoters and leaders went to great lengths to avoid working with other railroads, failing to see the larger picture of how interchange and a unified, national network could actually increase overall earnings and profits.

It was not until the 1880's that a uniform track gauge (4 feet, 8 1/2 inches) was finally settled upon. The industry only elected to use the knuckle coupler and automatic air brake, devices which not only brought far greater operational cost savings but also significant safety improvements, when required to do so by the federal government in 1893.

Into the early 20th century, railroads could not even agree on common boxcar dimensions and almost every company set forth its own practice in steam locomotive construction. Needless to say, it was a trying time.

An aerial view of the small Baltimore & Ohio yard in Portsmouth, Ohio, circa 1940's. Author's collection.

An aerial view of the small Baltimore & Ohio yard in Portsmouth, Ohio, circa 1940's. Author's collection.Aftermath

Despite its issues, the USRA set forth many standardized practices which forever benefited the industry, particularly when the Second World War broke out nearly twenty years later.

Mr. Stover notes these changes, highlighting that between 1921 and 1940 the industry witnessed a 17% increase in freight car capacity, 50% increase in serviceable freight cars, 30% increase in ton miles, and 45% increase in train speeds. All of this was achieved while requiring 31% less coal per 1,000 tons of freight handled.

It was all thanks to McAdoo and a committee of experts who realized additional cars and locomotives were needed to meet demand.

To remedy this, as well as streamline both the manufacturing and maintenance processes (and reduce costs), the USRA put together a mechanical committee featuring the industry's very best engineers.

They were tasked with standardizing locomotives and rolling stock which could be mass produced and utilized by any railroad. The former came in a variety of arrangements with main line power built as either "light" or "heavy" variants, depending upon track conditions.

In all, including requisitioned 2-10-0's from Russia, more than 2,000 locomotives with USRA specifications were placed into service. To read more about railroads in World War I please click here.