Transcontinental Railroad: Maps, Facts, Completion

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Who built the Transcontinental Railroad? It has been argued as the greatest single achievement ever accomplished within this great republic that we call the United States.

Perhaps even more impressive is the time required to do so; with virtually no mechanization whatsoever, crews from the Central Pacific and Union Pacific hacked out rights-of-way through empty wilderness in only six years!

Altogether, the entire project brought forth nearly 2,000 miles of new railroad. It was spearheaded by Abraham Lincoln although its roots trace back to the 1850's.

Our 16th President lobbied hard to see it finished, understanding its importance in protecting and uniting the country against the Confederacy. In the end, of course, its greatest legacy was settling the West.

Author and historian Mike Del Vecchio notes out in his book, "Railroads Across America," no other event in American railroading was quite as important.

With its completion, cross-country travel was reduced from months to mere days (although direct rail service was not possible until a bridge opened across the Missouri River between Omaha and Council Bluffs in 1872).

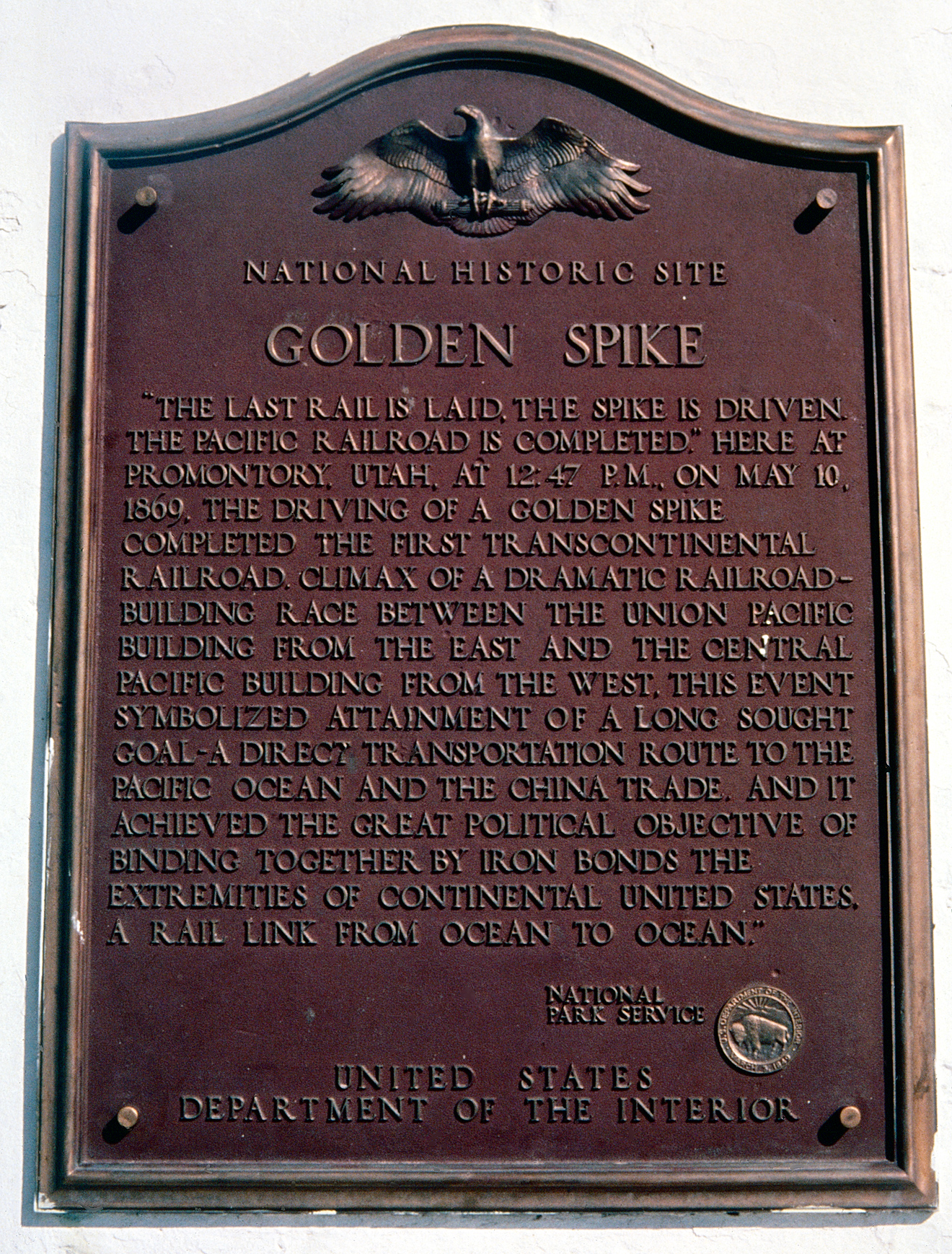

Today, the famous meeting at Promontory Summit, Utah, which officially signaled the Transcontinental Railroad's completion, no longer serves as an active rail line. However, the location, known as the Golden Spike National Historic Site, is maintained by the National Park Service and open to visitors.

Photos

History

There have been several excellent books published over the years that thoroughly cover the first Transcontinental Railroad subject. As a result, this article could, in no way, come close to those works.

However, it is my hope that the information presented here provides a brief synopsis on the topic. You may be surprised to learn that its genesis predates the Civil War's outbreak by nearly a decade.

According to the book, "The Northern Pacific, Main Street Of The Northwest: A Pictorial History" by author and historian Charles R. Wood in the spring of 1853 Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (who later became president of the Confederate States of America) initiated the task of surveying western routes to the Pacific Coast.

There were eight different options put forth running along various parallels from north to south. Due to the ongoing issue of slavery, however, Congress could not come to a consensus on which.

As a result the entire undertaking went dormant. Tensions between northern and southern states reached a crescendo when Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860.

Only weeks later, South Carolina formally seceded from the Union (December 20, 1860); soon afterwards several others followed, Confederate forces opened fire on federal troops stationed inside Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, and the Civil War was upon the nation.

Facts and Overview

$63,023,512 (Principal) $104,722,978 (Interest) $167,746,490 (Total) |

|

$16,000 (Flat Land) $32,000 (Foothills) $48,000 (Mountainous Terrain) | |

Sources (Above Table):

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Men Who Built The Transcontinental Railroad, The: Nothing Like It In The World. Pages 80-81, 95, 377. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. Pages 34-35. New York: Routledge, 1999.

- Vernon, Edward. Travelers' Official Guide Of The Railways And Steam Navigation Lines In The United States And Canada. "Union Pacific Railroad." June, 1870. Pages 215.

- Vernon, Edward. Travelers' Official Guide Of The Railways And Steam Navigation Lines In The United States And Canada. "Western Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads." June, 1870. Pages 216.

With the country in turmoil the North now had the freedom to choose whichever route it wished and settled on the central option.

As note, President Lincoln was a true believer in the Transcontinental Railroad, not only for its potential economic benefits but also its nationalistic importance.

Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809 and first entered politics at a very young age when, at just 23, he tried to gain a seat within the Illinois state legislature.

He had been fascinated by railroads since their introduction back east, believing they were the future in transportation.

In his authoritative book, "The Men Who Built The Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869: Nothing Like It In The World," author Stephen Ambrose notes that Lincoln stated during a campaign speech, "no other improvement...can equal in utility the rail road."

As a lawyer he defended the Illinois Central against the state in a case involving tax exemption. Then, on an even more important issue he won a landmark decision in 1857 regarding the railroads' right to bridge navigable waterways.

In that case, he successfully represented the Mississippi & Missouri Rail Road (predecessor to the better remembered Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad or "Rock Island").

It was the first to cross the mighty Mississippi River in 1856 but within a year a steamboat had collided with one of the bridge's piers. The steamboat company sued for the structure's removal but Lincoln successfully argued otherwise.

"Westward The Course Of Empire Takes Its Way." This Currier & Ives lithograph features the recently completed Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Author's collection.

"Westward The Course Of Empire Takes Its Way." This Currier & Ives lithograph features the recently completed Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Author's collection.Central Pacific

In 1853, Congress first directed Secretary Davis to survey three routes to the Pacific coast; the northerly line would run along the 49th parallel near the Canadian border, the central would depart from the small community of Omaha, Nebraska Territory (Nebraska achieved statehood on March 1, 1867) at the 42nd parallel, and finally the southerly corridor would follow the 32nd parallel.

Naturally, Southern loyalists, including Davis, argued for the latter and were so stubborn they refused to have any part in the enterprise if it built above the Mason-Dixon Line.

The standstill remained unchanged until Lincoln's election, which saw Southern senators and congressmen walk out. This left their Northern counterparts the easy decision of choosing the central option.

It was Greenville Dodge, an excellent engineer and decorated U.S. Army officer of the Civil War, who fervently believed, and ultimately swayed Congress, to back the Omaha routing.

From this community along the Missouri River it would follow the Platte River nearly all the way to the northeastern Colorado border.

At the town of North Platte, where the North Platte River and South Platte River split, the railroad would diverge slightly into Colorado, turn north along Lodgepole Creek into Wyoming Territory, slip past the Laramie Mountains, cross the Medicine Bow Mountains, and then head for the Green River.

Once in Utah the line would aim for Salt Lake City, then the only noteworthy western settlement. Beyond this point, Union Pacific's planners were rather uncertain since another endeavor, building east from Sacramento, California, was projected to meet them somewhere near the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

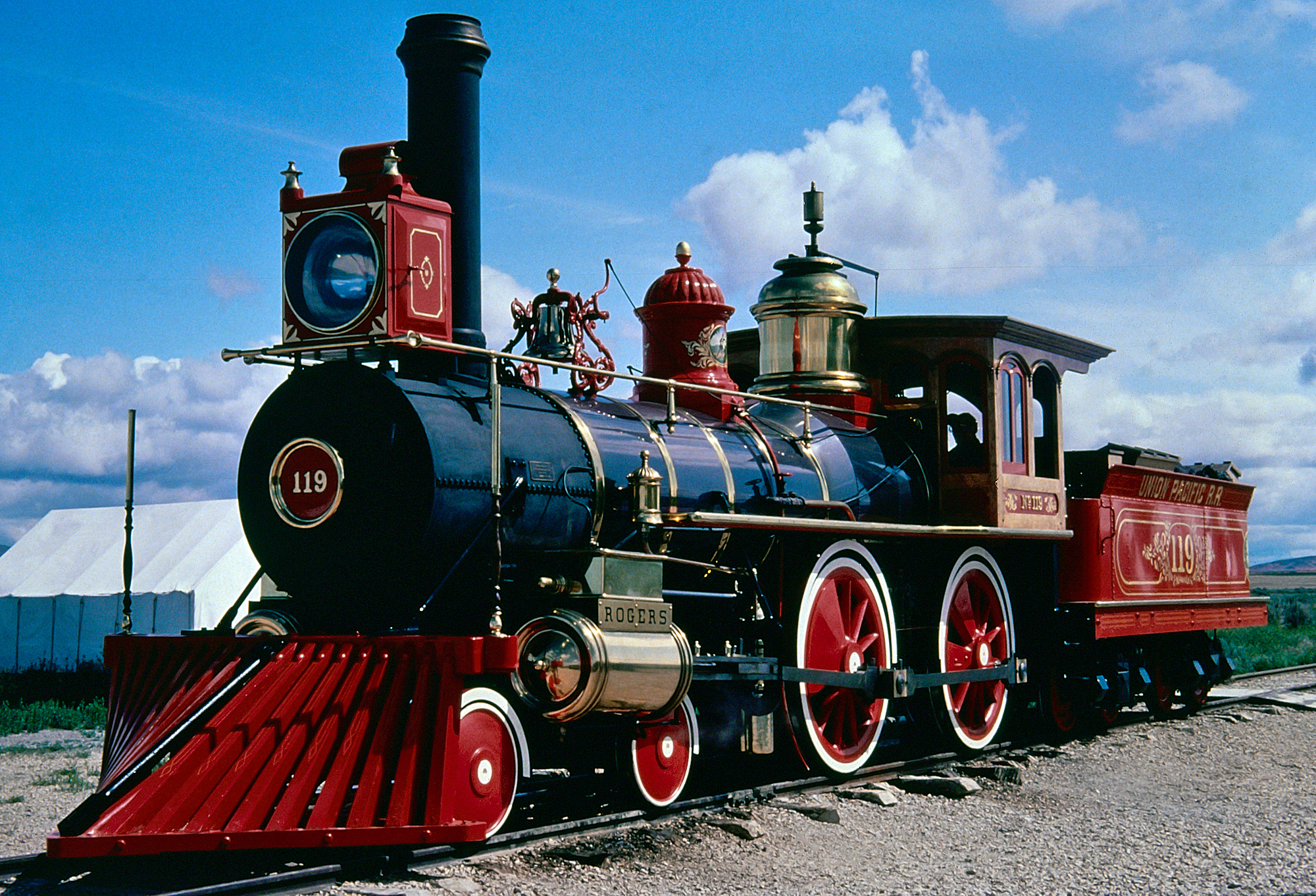

Union Pacific 4-4-0 #119 poses for a photo at the Golden Spike National Historic in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. This replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975. The original was built by the Rogers Locomotive & Machine Works of Paterson, New Jersey in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.

Union Pacific 4-4-0 #119 poses for a photo at the Golden Spike National Historic in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. This replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975. The original was built by the Rogers Locomotive & Machine Works of Paterson, New Jersey in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.The Transcontinental Railroad's western leg was known as the Central Pacific, the vision of Theodore D. Judah. While there were many who put great time, energy, and money into the venture his unyielding efforts in what he called "his" railroad (Central Pacific) laid the groundwork.

He firmly believed an acceptable route with manageable grades could be built through California's seemingly impenetrable Sierras.

In 1859 he began lobbying for it and on January 14, 1860 even opened what was the dubbed the "Pacific Railroad Museum" inside the Capitol building. Unfortunately, as with everything in Washington, both then and now, Congress was slow to act.

There were many doubters and Judah was severely handicapped by not having the necessary materials needed to convince naysayers. So, he sailed back to California and obtained these by single-handedly surveying the entire route himself.

As he had promised, Judah located a suitable grade over Donner Pass, running 115 miles from Sacramento to the Nevada state line.

On November 1, 1860 he wrote up a loose incorporation for the "Central Pacific Railroad Company of California" but could find no financial support in San Francisco.

With no interested in San Francisco he traveled east to nearby Sacramento and located four businessmen eager and willing for just such a railroad; Charles Crocker, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Leland Stanford.

These individuals carried the monetary support necessary for incorporation under California state law (which in this case totaled $115,000 (or $1,000 per mile) and as a result, the Central Pacific Railroad of California (CP) was born on June 28, 1861.

Sadly, despite all his hard work, the so-called "Big Four" eventually pushed their chief engineer out of the picture.

Before Judah's death on November 2, 1863 (while attempting to wrest control from the group) he was able to witness the Pacific Railroad Act became law on July 1, 1862 with President Lincoln's signature To see a complete transcript of this act please click here.

It was directed to:

"construct a railroad and telegraph line from the Pacific coast, at or near San Francisco, or the navigable waters of the Sacramento River, to the eastern boundary of California."

With the passage of this act the CP adopted the agreement on October 7th and formally accepted it through the Department of the Interior on December 24th. To actually build the railroad, however, would require a great deal of land grants.

Thanks to Senators Stephen A. Douglas (Illinois) and William R. King (Alabama) there was legislation drawn up for this purpose in 1850, which assisted in establishing new railroads west of the Mississippi River.

John Stover's book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," notes that between 1850 and 1871 the U.S. government offered railroads 170 million acres of land to construct 80 different initiatives. During this time about 131 million acres were actually used, which helped build 18,738 miles of new railroad.

One of the first to utilize land grants was the Illinois Central, which completed its original main line in 1856. For the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, they would receive ten alternate sections of federal land for each mile of track laid (or roughly 6,000 acres).

According to the book, "Union Pacific Railroad," by historians Joe Welsh and Kevin Holland, an amended Pacific Railroad Act of 1864 increased this figure to twenty alternate sections (or around 12,000 acres for every mile completed). Additionally, there were government loans which varied from $16,000 to $48,000 per mile (depending on the topography).

For Central Pacific, there was a catch, however; it was required to complete 50 miles within its first two years, 50 miles each year afterwards and be finished entirely by July 1, 1876 or lose all rights to its land grants and forfeiture of federal loans. On January 8, 1863 the CP formally got underway during a ceremony held in Sacramento.

Curiously, only two members of the five founders were present, Governor Stanford (elected in 1861) and Charles Crocker; Huntington was in New York attempting to procure additional funding, Judah was back in the Sierras surveying, and Mark Hopkins simply wasn't interested in attending.

The replica of Union Pacific 4-4-0 #119 and Central Pacific 4-4-0 #60, the "Jupiter," at the Golden Spike National Historic Site in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. The "Jupiter" replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975 while the original was built by the Schenectady Locomotive Works of Schenectady, New York in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.

The replica of Union Pacific 4-4-0 #119 and Central Pacific 4-4-0 #60, the "Jupiter," at the Golden Spike National Historic Site in Promontory Summit, Utah circa 1982. The "Jupiter" replica was completed by O'Connor Engineering in 1975 while the original was built by the Schenectady Locomotive Works of Schenectady, New York in 1868. American-Rails.com collection.Union Pacific

Although both companies' track crews worked at a marvelously feverish pace, the Transcontinental Railroad wasn't exactly a fluid concept.

It was slow in developing even after President Lincoln signed the 1862 act into law, which did not stipulate a meeting point aside from Central Pacific reaching the Nevada border and Union Pacific heading west of Omaha.

After CP's groundbreaking, UP officials became increasingly impatient to get started; while this was technically not a race, all those involved clearly understood that whoever built more mileage would garner more money through loans and land grants.

The UP (formally organized in May of 1863) was the only one actually created under the 1862 act; while Dodge fought for the Omaha routing, and later became a prominent figure in its construction, he was initially lured away to do his part in the Civil War.

This left Thomas C. Durant (As vice president and general manager, he was the most influential player at Union Pacific and was eventually successful in pulling Dodge away from the Army.) in control along with Peter Day (chief engineer), Samuel B. Reed (chief of construction), and the wealthy Ames brothers from Boston (Oliver and Oakes) who provided vital financial assistance.

Union Pacific held its official groundbreaking ceremony on December 1, 1863, which included a great deal more pomp and circumstance than CP's; the governor of Nebraska Territory, Alvin Saunders, turned the first shovel of dirt while the day was filled with fireworks, cannon salutes, bands, and much more.

Unfortunately, UP encountered controversy before work even got underway. As means of procuring the necessary capital and protecting stockholders' investments, a separate company was formed to handle all construction contracts.

It was the idea of George Francis Train who, with Durant's blessing and assistance, purchased a small Pennsylvania company, the Pennsylvania Fiscal Agency, for $50,000 in March of 1864. They subsequently renamed it the Crédit Mobilier of America.

As Mr. Ambrose's book details the scheme worked by having UP award contracts to paper corporations/individuals who then assigned them to Crédit Mobilier; essentially, all monies (largely federal loans) flowed through this company.

It would then purchase UP stocks and bonds at par and sell them for a profit. It mattered not whether the railroad actually made money, or was even finished; those involved with Crédit Mobilier would reap huge profits.

It became a major scandal that nearly bankrupted the railroad. The extra profits were then merely pocketed by Durant and his partners. The issue wasn't resolved until 1872 although little punishment was ever handed down to those responsible.

By December of 1864, Dey had graded some 23 miles west of Omaha but was then told to change the route (following Mud Creek) in an attempt to amass additional profits for Crédit Mobilier and more land grants. Disgusted, he resigned on December 7th and was later replaced by Greenville Dodge.

It took Durant several years to finally persuade the noted engineer to leave the army. When the Transcontinental Railroad got underway, Dodge originally agreed to join UP once the war was over. When hostilities ended and he still failed to show, Durant became exasperated.

At the time, Dodge was leading regiments west of the Missouri River as head of the Department of the Missouri to eliminate the Indian threat which stretched from the Plains to the Rocky Mountains. He finally signed on with Union Pacific in the spring of 1866 and was given complete authority.

Like Judah at Central Pacific, no other individual was quite as important to Union Pacific as Greenville Dodge; he brought strong, militaristic leadership that got things done quickly and efficiently. He was further aided by an army of Irish veterans, who were already well-versed in taking orders.

Construction

There is no doubt that Union Pacific's feat was masterful in its own right although it can be strongly argued that Central Pacific's endeavor was more impressive given its private incorporation and the added difficulty of laying a grade through the rugged Sierra Nevada's.

It also had to ship all new equipment, supplies, and construction materials 15,000 miles around South America's Cape Horn to reach California.

In his book, "Southern Pacific Railroad," author Brian Solomon points out that actual work commenced some ten months after the formal groundbreaking festivities.

While the Chinese workers worked tirelessly and efficiently, it was Collis Huntington who kept the money flowing and things on schedule; the CP got underway from downtown Sacramento near the Sacramento River waterfront with an initial task of bridging the American River a few miles to the west.

On October 26, 1863 the first rails were spiked down and soon, tracks reached nearby 21st Street.

Just a few weeks later, on November 10th, the company's first locomotive, the 46-ton, 4-4-0 Governor Stanford (an 1862 product of the Norris Locomotive Works, this machine is preserved today at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento), made its first run over this stretch, which drew great fanfare.

Tunnels

Tunnel #1: Located at Grizzly Hill, 514.7 feet in length. The bore was widened in 1913 to support double-tracking.

Tunnel #2: Situated about 1 mile east of Emigrant Gap, this bore was 271 feet in length; daylighted 1923-1924.

Tunnel #3: This bore is at Milepost 180.7 near Cisco. When originally built it was 280 feet in length.

Tunnel #4: Very near Tunnel #3 at Milepost 181, it was originally 92 feet in length.

Tunnel #5: Located only four miles west of Tunnel #4 at Milepost 185, it was 128 feet in length; daylighted in 1895.

Tunnel #6: The famous bore in the Sierras also known as "Summit Tunnel" it was 1,659 feet in length. The structure was bypassed in 1997.

Tunnel #7: Situated at Milepost 194.1 it is 100 feet in length; later daylighted and then covered with a snowshed before being abandoned.

Tunnel #8: This structure sits at Milepost 194.3 near Black Point. It is 375 feet in length and is no longer in service.

Tunnel #9: This bore is located at Milepost 194.9 and is 216 feet in length; now abandoned.

Tunnel #10:This tunnel is at Milepost 195.1 and is 509 feet in length; now abandoned.

Tunnel #11: Based at Milepost 195.4 it is 577 feet in length, now abandoned.

Tunnel #12: At Milepost 195.7 it is only a mile west of Tunnel #11; the structure is 342 feet in length and is now abandoned.

Tunnel #13: Situated at Milepost 200.1 near Andover it is the second-longest at 870 feet in length.

Tunnel #14: Located at Milepost 222 it is 200 feet in length and was bypassed following a line change in 1913.

Tunnel #15: Located at milepost 225 (Quartz Spur); originally 96 feet in length. The bore was daylighted in 1895 and the grade was abandoned in 1913 following a line change.

By early 1864 the relatively gentle topography directly east of Sacramento allowed crews to complete 22 miles quite quickly.

On March 25th, the very same Governor Stanford pulled a load of granite from nearby mines, which provided the Central Pacific its first revenue freight earnings. On May 13, 1865 service opened to Auburn, a location that also marked the Sierra's foothills.

The right-of-way roughly followed the North Fork of the American River as it passed through Colfax, Dutch Flat, and Emigrant Gap before reaching Summit Tunnel (tunnel #6) near present-day Norden.

As its name implied, this bore was situated at the summit of Donner Pass and was the longest of the fifteen tunnels needed through the mountains (excluding snow sheds); it was 1,659 feet in length and 124 feet deep. It was finished in August of 1867 a full year since it had all began (August 27, 1866).

It sat a 7,042 feet above sea-level and was blasted out of the mountain using nothing more than picks, shovels, black powder, nitroglycerin, and considerable sweat and blood. It had so delayed ongoing work that grading crews had pushed ahead into Nevada months earlier.

Map

Seen above is a route map of the first Transcontinental Railroad (not-to-scale), completed between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads.

Note how UP was much larger thanks to the easier topography it was able to navigate between Promontory Summit, Utah and Omaha, Nebraska. The CP, on the other hand, had to contend with the rugged Sierra-Nevada Mountains.

After Summit Tunnel received its rails on November 30, 1867 the pace quickened and on June 18, 1868 the CP's tracks reached Reno, Nevada (154 miles east of Sacramento).

By then, Greenville Dodge was blazing his way across the Great Plains. In some cases, graders were some 200 miles ahead of track-layers!

The UP's progress was as follows: by late July of 1866 it stretched 153 miles to Grand Island; on October 6th rails were 247 miles west of Omaha; and finally by September 21, 1868 the line had reached the Green River, more than 750 miles from the Missouri River.

The speed of construction led to the infamous "Hell On Wheels," a traveling town which followed the railroad.

It was little more than a collection of partying, gambling, drinking, and promiscuous behavior enabling workers to relax after a hard day's work.

While Union Pacific's leadership struggled to keep this wildness under control the bigger issue turned out to be Indians. At first, UP had no trouble and the local Pawnee even assisted in the work.

However, west of central Nebraska the Cheyenne and Sioux were not so friendly; these tribes regularly attacked survey parties and construction crews in an attempt to turn back the white man.

Dodge initially felt his men could deal with the problem directly by remaining armed at all times. But with victims being horribly mutilated and the attacks continuing, federal troops were eventually required.

Completion

The last year of construction, particularly the final six months, were a blitzkrieg; once the Central Pacific cleared the Sierra's they raced eastward across the Nevada desert while Union Pacific did the same through Wyoming.

As each railroad entered Utah the race took on a whole new meaning with both wanting to build just a little further than the other; CP had survey crews as far as east as Echo Canyon, Utah and UP as far west as Humboldt Wells, Nevada.

It was more than just pride, however. As the book, "Railroads In The Days Of Steam," notes the government was paying upwards of $96,000 for every new mile the Transcontinental Railroad constructed, which included a 400-foot-wide right-of-way.

Obviously, not only did more mileage mean more territory but also greater revenue. The issue came to head in early 1869 when Union Pacific and Central Pacific grading crews met between Ogden and Promontory where, in some cases, they were only a few feet apart!

Neither side wanted to give in although it was obvious time, money, effort, and resources were being wasted. Today, these redundant grades can still be seen. Finally, on April 9, 1869 Greenville Dodge and Collis Huntington met in Washington, D.C. and agreed the official meeting point would be Promontory Summit, Utah.

The Great Salt Lake

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, Greenville Dodge originally considered crossing the Great Salt Lake via a causeway as the Union Pacific approached Ogden.

Although an incredibly expensive endeavor, doing so would have offered easier grades and fewer miles.

However, when the lake was sounded he discovered it to be 14 feet higher in 1868 than it had been nineteen years earlier. As a result, he deemed the project unfeasible. In the end, the great lake was crossed.

Several decades later, in 1899, plans commenced on a water level route that would directly span the lake to its north with Lucin as the western terminus of the old alignment.

The Ogden & Lucin Railroad was a paper company created for the express purpose of building the Lucin Cutoff and work officially began in March of 1902.

It was originally hoped the route would be a complete causeway, similar to what was built later. However, construction techniques at the time, while advanced, were not able to stabilize the right-of-way, as it kept sinking below the water's surface.

As a result, engineers decided on a more conventional approach; long earthen approaches built of stone-fill with a wooden trestle in the center. The cutoff officially opened on January 1, 1905.

Surprisingly, the old Promontory Branch remained in service for several years until it was finally abandoned during June of 1942. In June of 1959 a new causeway replaced the original structure.

As part of the deal, Central Pacific purchased Union Pacific's trackage from Ogden to Promontory Summit (totaling about 50 miles) for $4 million. The agreement was also spurred for monetary reasons as the newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant put an end to public subsidies.

And, just like that, the Transcontinental Railroad's "Great Race" was over; Union Pacific was finished first, reaching Ogden (1,028 miles from Omaha) on March 7, 1869.

Central Pacific required another month but by April 17th had finished to Monument Point, more than 672 miles east of Sacramento and just 20 miles west of Promontory Summit.

The two railroads' grand ceremony and meeting was originally scheduled for May 8th but due to heavy rains in the Weber Canyon, Union Pacific's train was delayed. As a result, the festivities were pushed back to Monday, May 10th.

Several dignitaries were present including:

- Leland Stanford

- James Harvey Strobridge (chief of construction) of Central Pacific

- Greenville Dodge

- Thomas Durant

- John Duff (director)

- Sidney Dillon (director and head of the Crédit Mobilier)

- Samuel B. Reed

- Herbert M. "Hub" Hoxie (An Iowa delegate who was later awarded a construction contract to build UP's first 100 miles. When Dodge took command, he was given a job as transfer agent out of Omaha.)

- Jack and Dan Casement (brothers who led track-laying gangs),

- Colonel Silas Seymour (Officially listed as a consulting engineer, he is said to have had no real authority although was promoted by and answered to only Durant.)

Railroads Comprising

The "Big Four"

Today

There was also the train crews; Central Pacific's 4-4-0 #60, "The Jupiter," was headed by George Booth (engineer), R.A. Murphy (fireman), and Eli Dennison (conductor) while Union Pacific's 4-4-0 #119 had Sam Bradford at engineer, Cyrus Sweet as fireman, and Benjamin Mallory (conductor).

The famous "Golden Spike" was the work of David Hewes from San Francisco, a businessman who wanted to invest in the CP project from the start but did not have the money to do so.

The intricate decoration was six inches long but not of solid gold. Instead, only a large, 18-ounce gold nugget sat atop it with the entire piece was valued at $350 (today, it is preserved at Stanford University).

Finally, there was a "Last Tie" crafted from beautiful laurel wood and a silver-headed hammer. Once everything was in place, Stanford was given the honor of driving the spike; afterwards a local telegrapher wired the word "Done!" With that, great celebrations erupted throughout the country.

The Transcontinental Railroad's most famous image was taken when The Jupiter and Union Pacific's 4-4-0 #119 were photographed coupler-to-coupler as many dignitaries and patrons surrounded the locomotives.

Today, you can see two of the original Golden Spikes (a total of six were used); the original is housed at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University and another is on display at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

Sources:

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Men Who Built The Transcontinental Railroad, The: Nothing Like It In The World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

- Del Vecchio, Mike. Railroads Across America. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1998.

- Kelly, Jack. Edge Of Anarchy, The: The Railroad Barons, The Gilded Age, And The Greatest Labor Uprising In America. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2019.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Solomon, Brian. Southern Pacific Railroad. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2007.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

- Welsh, Joe and Holland, Kevin. Union Pacific Railroad. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2009.

- Wood, Charles R. The Northern Pacific, Main Street Of The Northwest: A Pictorial History. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1968.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved. -

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway: Map, Logo, History

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a famous southern line that operated from Norfolk to Chicago and through much of Michigan. -

C&O 4-8-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 12, 25 09:52 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's fleet of 4-8-4s, listed as Class J-3/a, included twelve examples of 4-8-4s the railroad termed "Greenbriers." Today, #614 survives.