C&O's "The Chessie" (Streamliner): History, Consist, Photos

Last revised: February 27, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Chesapeake & Ohio did not spend lavishly on its passenger trains until Robert Young became chairman in 1942. The Chessie was one his concepts,

He fervently believed the service was an important and integral part of a railroad's business. In addition, through offering high quality customer service and exquisite accommodations Young felt these trains could remain profitable in the postwar era.

This belief led to the creation of "The Chessie," an all-new, all-coach service between Washington, D.C. and Cincinnati, Ohio. The train was also envisioned to be entirely steam powered using a new type of technology, steam turbines.

C&O officials believed coal could be harnessed efficiently in such a locomotive and effectively compete against the newfangled diesel-electric. The railroad also had another incentive to invest in steam turbines, a cheap and steady source of fuel, coal.

Young wanted to launch The Chessie directly after World War II. However, Pullman was backlogged with orders. The equipment ultimately did not arrive until the early 1950s at which point sagging ridership - and mechanical issues with the steam turbine - convinced even Young to abandon the concept.

Photos

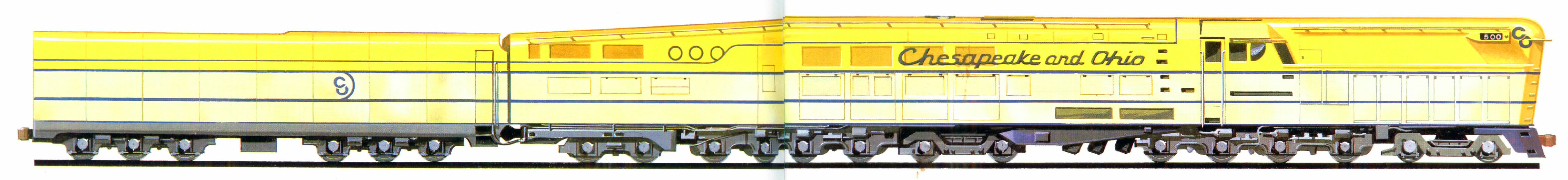

Chesapeake & Ohio M-1 steam turbine #500 on display at the Chicago Railroad Fair in 1948. The railroad was quite proud of its product, as noted by the sign, but alas it never saw regular service.

Chesapeake & Ohio M-1 steam turbine #500 on display at the Chicago Railroad Fair in 1948. The railroad was quite proud of its product, as noted by the sign, but alas it never saw regular service.Robert Young

While the C&O had historically focused primarily on its freight business, particularly coal, it did field a small fleet of fine trains including the George Washington, Sportsman, and Fast Flying Virginian (F.F.V.). When Robert Young became president in 1942 everything changed.

He believed strongly in this business with intentions of seriously upgrading the railroad's passenger department after World War II. Believing the C&O should take full advantage of the robust travel business he quickly placed orders for new equipment from the Budd Company and Pullman-Standard.

However, the backlog for streamlined cars at the time delayed the new equipment's arrival for more than two years; a situation which would eventually doom the Chessie.

Development

An early 1944 order from Budd had arrived by the summer of 1946 allowing the C&O to launch its new regional streamliner, the Pere Marquette, between Detroit and Grand Rapids, Michigan that August.

The trains operated via subsidiary Pere Marquette Railway and very successful, further cementing Young's belief in postwar passenger service.

According to Thomas Dixon, Jr.'s, "Chesapeake & Ohio Passenger Service: 1847-1971," the C&O boasted the Chessie as the most luxurious all-coach train ever launched.

The name carried deep roots within the company's culture as "Chessie, The Sleeping Kitten" had became a marketing sensation when the little fur feline debuted in 1933. The iconic mascot became the unofficial symbol of the C&O throughout its corporate existence, which led to the railroad's nickname as "Chessie."

M-1 Steam Turbine

In addition to the C&O's bold statement of luxury, the train was also powered by new technology, a steam-turbine locomotive designed by General Electric and Baldwin, dubbed the Class M-1.

The railroad intended to utilize these massive locomotives in handling The Chessie for the duration of its trip with fueling stops at Clifton Forge, Virginia and Hinton, West Virginia.

In a photo that appears to have been taken just before its delivery to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum we see Chesapeake & Ohio 4-6-4 #490 (L-1) at the railroad's Huntington, West Virginia engine shops, circa 1968.

In a photo that appears to have been taken just before its delivery to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum we see Chesapeake & Ohio 4-6-4 #490 (L-1) at the railroad's Huntington, West Virginia engine shops, circa 1968.Unfortunately, while steam-turbines were powerful and fast on paper they were an unproven design. The three streamlined M-1's built, #500-502, carried a 2-C1+2-C1-B wheel arrangement and ultimately never got the chance to prove themselves in service due to their poor performance during testing.

The locomotives were completed between 1947 and 1948; after only a few years on the road the turbines were scrapped in 1950.

Streamlined Cars

In 1946 the Chesapeake & Ohio placed a 48-car order from Budd for its new Chessie (which included domes, lounges, diners, and coaches) followed by a massive 287 car order on November 19th from Pullman-Standard to reequip its entire passenger fleet with all-new, lightweight equipment.

According to Mike Schafer and Joe Welsh's book, "Streamliners: History Of A Railroad Icon," the C&O's research department, headed by Ken Brown, was heavily involved in the development of these new cars. Instead of accepting designs that were more-or-less "off the shelf" the C&O went its own way.

Some of its more notable improvements included moving bedrooms to the center of sleepers where the ride was smoother, partitioning coaches to provide a more open feel for passengers during their trip, providing twin-unit diners, baby changing rooms, a theater for kids, and even goldfish aquariums!

Aside from the Chessie's radical car designs Young was ahead of his time with customer service offering a type of early credit card system, passenger representatives available on every train, hostesses, pay-on-train ticketing, the C&O's Central Reservation Bureau that enabled travelers to call toll-free and book a trip, and the discontinuance of tipping porters and waiters.

Such a considerable departure from traditional, conservative industry ideas was thanks to Young's non-railroading background, a man who hailed from broader business roots. Alas, even his visionary thinking could not save the C&O's passenger business although he continued efforts to curb the losses until moving on the New York Central chairmanship in 1954.

Setbacks and Cancellation

With the Chessie's new equipment delayed until mid-1948, and the rest even later, it was clear Young's hope of launching the train directly after the war would not transpire.

Along with continually sagging patronage the Chessie was quietly shelved that same year. The cars were transferred in October to the Pere Marquettes and subsequently sold a few years later.

The large, 287-car order was partially delivered with the C&O taking on 151 by the spring of 1950 while the rest on order had been picked up by other railroads; 33 of the cars eventually delivered were quickly sold as well with the rest used to reequip the remaining heavyweight coaches and Pullman sleepers then still in service.

Sources

- Dixon, Thomas W. Chesapeake And Ohio Railway: A Concise History And Fact Book. Clifton Forge: Chesapeake & Ohio Historical Society, 2012.

- Dixon, Thomas W. Chesapeake & Ohio Passenger Service: 1847-1971. Clifton Forge: Chesapeake & Ohio Historical Society, 2013.

- Schafer, Mike and Welsh, Joe. Streamliners, History of a Railroad Icon. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2003.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

New Mexico Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 23, 25 02:25 PM

The enchanting state of New Mexico, known for its vivid landscapes and rich cultural heritage, is home to a number of fascinating railroad museums. -

New Hampshire Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 23, 25 02:11 PM

New Hampshire, known for its breathtaking landscapes, historic towns, and vibrant culture, also boasts a rich railroad history that has been meticulously preserved and celebrated across various museum… -

Minnesota Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 22, 25 12:17 PM

The state of Minnesota has always played an important role with the railroad industry, from major cities to agriculture. Today, several museums can be found throughout the state.