- Home ›

- Locomotives ›

- Tender

Steam Tenders: Providing Fuel and Water Storage

Last revised: November 5, 2024

By: Adam Burns

A steam locomotive's tender became a very common piece of equipment, so much so that an engine did not look right without one trailing behind it!

The device, which can trace its history back to earliest of locomotive designs had a simple but vital purpose holding additional fuel (coal, wood, or oil in later years) and water which greatly extended the operational range from a few miles to 100 or more.

As locomotives increased in size and power so too did the tender with many variants along with their own particular names and designers.

Today, the biggest tenders in service are found on a handful of large wheel arrangements still in operation. Most notable is Union Pacific 4-8-4 #844 and 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" #4014 (there are no plans to operate 4-6-6-4 #3985 in the foreseeable future).

You can also find big tenders in service behind other larger steamers still running including Norfolk & Western 4-8-4 #611; Spokane, Portland & Seattle 4-8-4 #700, Southern Pacific 4-8-4 #4449, and Milwaukee Road 4-8-4 #261. Finally, there are a handful of other big examples awaiting restoration.

Seen here is the big 22,000 gallon tender of Southern Pacific 4-8-8-2 "Cab Forward" #4272 (AC-11) at Colton, California in 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Seen here is the big 22,000 gallon tender of Southern Pacific 4-8-8-2 "Cab Forward" #4272 (AC-11) at Colton, California in 1955. American-Rails.com collection.The tender began as a simply a small, two-axle carriage employed on the earliest English-built locomotives of the 1820s to haul additional fuel and water.

As the fledgling industry gained its footing within the United States during the 1830s, and then rapidly expanded by mid-century, more powerful locomotive designs were needed to meet demand.

The first common, widespread wheel arrangement put into service which offered sufficient power and speed was the 4-4-0 "American."

This type became so popular that it was still being employed by the end of the steam era a century later. In regards to the tender's development the American was the first to use the now-standard rectangular design.

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6060, toting a Vanderbilt Tender typically found on CN locomotives, is seen here leading an excursion at St. Lambert, Quebec on September 15, 1973. Carl Sturner photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Canadian National 4-8-2 #6060, toting a Vanderbilt Tender typically found on CN locomotives, is seen here leading an excursion at St. Lambert, Quebec on September 15, 1973. Carl Sturner photo. American-Rails.com collection.According to Wes Barris' SteamLocomotive.com, the common tender may have looked uniformly rectangular from the outside but seen from above it was all utilitarian sporting a fuel bunker (where fuel or wood was stored) surrounded by a "U" shaped water jacket.

After coal became the common source of fuel by the latter 19th century (replacing wood) the bunker was designed to slope downward towards the locomotive cab thereby employing gravity and making it easier for the fireman to do his job.

As Wes goes on to state a tender's layout was usually configured to hold much more water than fuel since the former exhausted at a much higher rate than the latter.

As a general rule of thumb, one pound of coal could turn six pounds of water (0.7 gallons) into steam resulting in a tender's ratio comprising roughly 14 tons of coal for every 10,000 gallons of water.

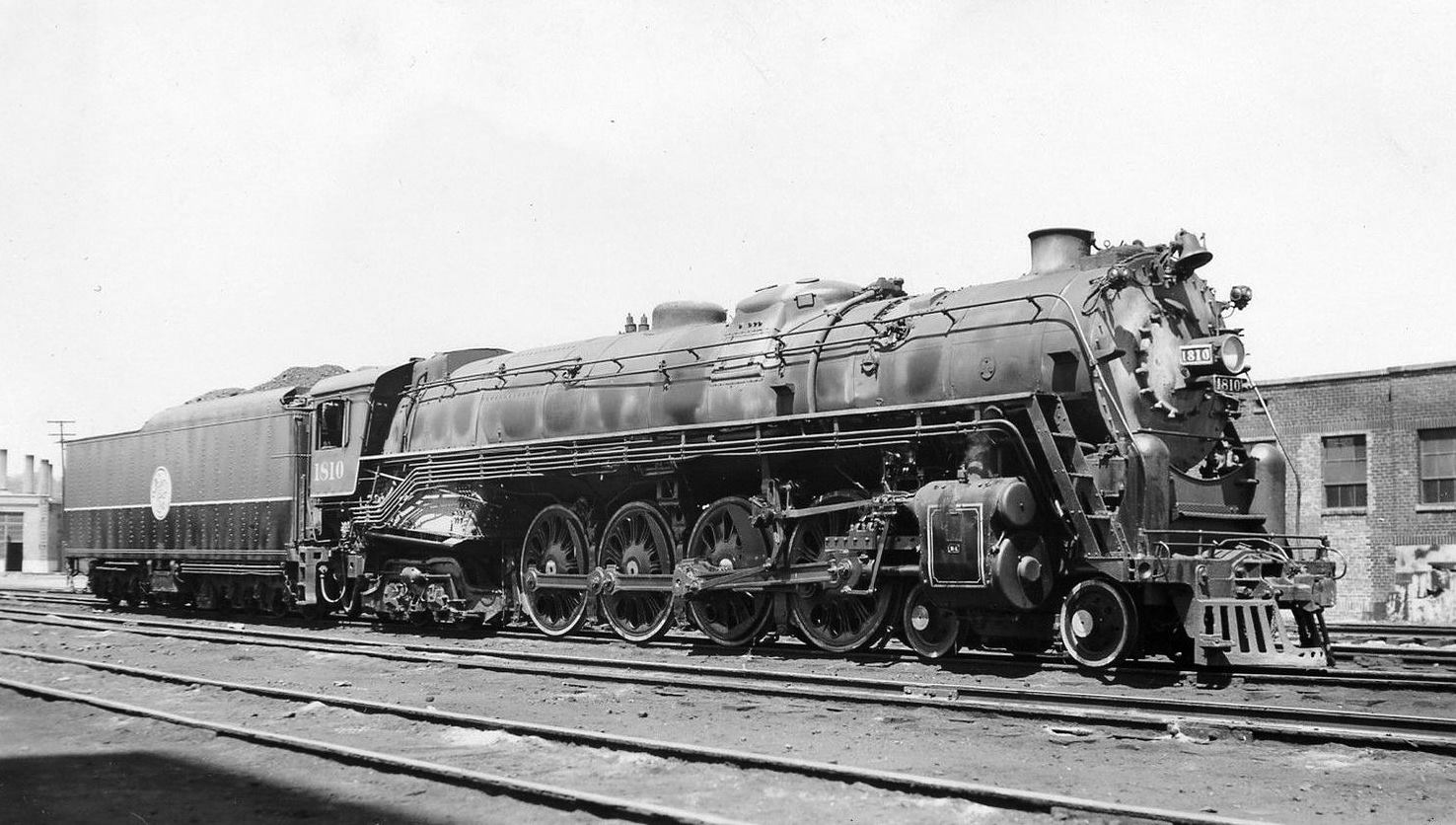

Atlantic Coast Line 4-8-4 #1810 (R-1), one of twelve "1800s" the railroad acquired from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1938. Acquired for passenger serviced but disliked by the ACL due to counterbalancing issues they were retired as soon as new E3's and E6's from Electro-Motive were available. Their tenders could handle 24,000 gallons and 27 tons of coal.

Atlantic Coast Line 4-8-4 #1810 (R-1), one of twelve "1800s" the railroad acquired from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1938. Acquired for passenger serviced but disliked by the ACL due to counterbalancing issues they were retired as soon as new E3's and E6's from Electro-Motive were available. Their tenders could handle 24,000 gallons and 27 tons of coal.As locomotive technology advanced, especially during the 20th century, so too did the tender and there were several variants put into service over the years. The most common, non-rectangular types are included here.

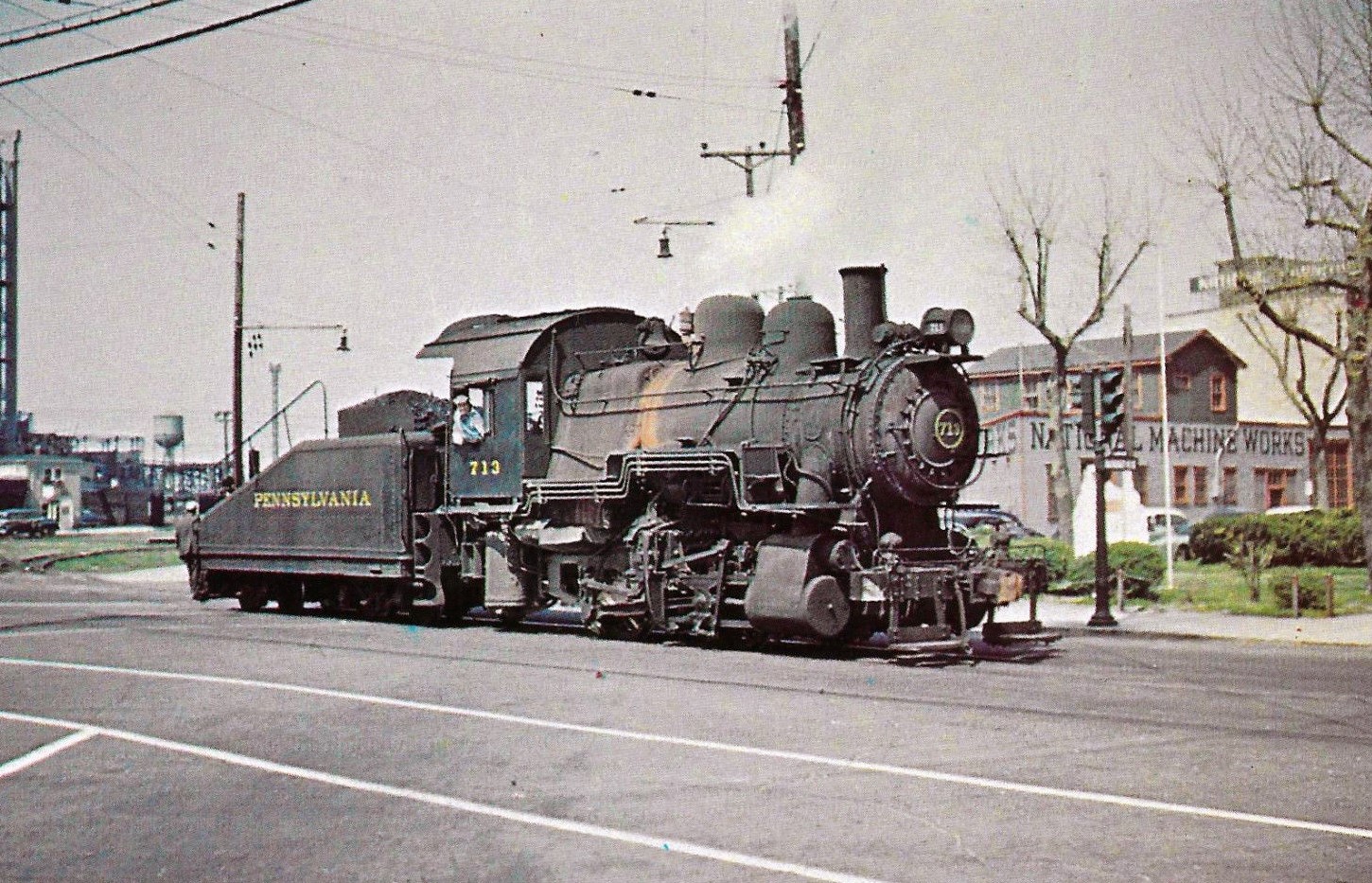

The best known of all, at least in regards to shear numbers employed, was the slope back tender. These were found on thousands of switchers (0-4-0's, 0-6-0's, 0-8-0's, etc.) which usually never left the yard, spending their time breaking apart and rebuilding trains.

As a result, they did not consume large amounts of fuel or water (and even if they did, more was close at hand) and a large tender was not warranted. So, railroads came up with a small design that sloped sharply at the aft end, which provided crews with better visibility.

One of Southern Pacific's workhorse 2-8-0's, #2514 (C-9), with its little Vanderbilt Tender is seen here in Los Angeles, circa 1950s. Mac Owen collection.

One of Southern Pacific's workhorse 2-8-0's, #2514 (C-9), with its little Vanderbilt Tender is seen here in Los Angeles, circa 1950s. Mac Owen collection.Vanderbilt

Perhaps the most widely used variant in main line applications was the so-called "Vanderbilt Tender." This design was patented by Cornelius Vanderbilt (great grandson of the legendary "Commodore" Vanderbilt) in 1901 and employed a cylindrical design instead of a squarish box.

It offered additional structural strength with more storage all the while being lighter than traditional tenders. Interestingly, even though Vanderbilts were never built with style in mind but their rounded features actually provided for a semi-streamlined, pleasing appearance from a visual aspect.

For instance, the Baltimore & Ohio was a big user of Vanderbilts and their 4-8-2's (the Class T-3t variants) were a great looking locomotive. Aside from the B&O other railroads employing the tender included the Canadian National, Grand Trunk Western, Great Northern, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific.

Canadian Pacific 4-6-0 #972 has Extra 972 West at Chaplin, Saskatchewan on August 27, 1959. Built by Sachsische Maschinenfabrik in 1903 its little tender could hold 6,000 gallons and 11 tons of coal. According to SteamLocomotive.com, this Ten-wheeler is currently stored, dismantled, at the Strasburg Railroad. Carl Sturner collection.

Canadian Pacific 4-6-0 #972 has Extra 972 West at Chaplin, Saskatchewan on August 27, 1959. Built by Sachsische Maschinenfabrik in 1903 its little tender could hold 6,000 gallons and 11 tons of coal. According to SteamLocomotive.com, this Ten-wheeler is currently stored, dismantled, at the Strasburg Railroad. Carl Sturner collection.Whale Back Tenders

These interesting contraptions found limited use across the industry and were sometimes known as "turtle back" tenders.

Most often used on early Mallet or articulated designs they looked like a Vanderbilt cut in half and laid on its side with two separate tanks with one holding fuel (usually oil) and the other water. By the late steam-era most of these had disappeared, at least on new designs.

The Long Haul Tender was a PRR novelty, seen here on 4-4-4-4 "Duplex" #5519 ahead of train #30, the "Spirit of St. Louis," near St. Jacob, Illinois on June 17, 1946. Otto Perry photo.

The Long Haul Tender was a PRR novelty, seen here on 4-4-4-4 "Duplex" #5519 ahead of train #30, the "Spirit of St. Louis," near St. Jacob, Illinois on June 17, 1946. Otto Perry photo.Long Haul

A massive design, Long Haul Tenders were most commonly found on the Pennsylvania Railroad and most famously used on the 4-4-4-4 "Duplex Drive" (T-1) locomotives.

They could hold an incredible amount of fuel (around 20,000 gallons of water and 42 tons of coal), which required a pair of four-axle trucks (eight wheels each).

Few other lines used them in regular service although the Santa Fe had Baldwin attach Long Hauls to their final thirty "2900 Class" 4-8-4's outshopped between 1943-1944.

Feather River Lumber Company 2-6-6-2T #4 pulls away from the water tank at Crocker within California's Sierra Nevadas near Loyalton during 1957. The little Mallet was built as Clover Valley Lumber Company #4 by Baldwin in 1924. When logging operations ceased in 1958 the locomotive held an uncertain future and was once used as a stationary boiler in Reno, Nevada. Today, it has been fully restored as Clover Valley #4 operating on the Niles Canyon Railway in Sunol. Ken Yeo photo.

Feather River Lumber Company 2-6-6-2T #4 pulls away from the water tank at Crocker within California's Sierra Nevadas near Loyalton during 1957. The little Mallet was built as Clover Valley Lumber Company #4 by Baldwin in 1924. When logging operations ceased in 1958 the locomotive held an uncertain future and was once used as a stationary boiler in Reno, Nevada. Today, it has been fully restored as Clover Valley #4 operating on the Niles Canyon Railway in Sunol. Ken Yeo photo.Centipede

The most famous of all large tenders was the Centipede, which first entered service in the late 1930s. They derived their name from their many axles, five in all that were rigidly mounted but could move laterally; in addition they were equipped with a two-axle lead pilot which provided steering into curves (similar to a locomotive's front truck).

Centipedes were found on large, late era "Super Power" and articulated locomotives which consumed vast amounts of fuel and water. According to SteamLocomotive.com the best known include:

- Boston & Maine's 4-8-2's (R-1)

- Rio Grande's 4-6-6-4's (L-97)

- Missabe's 2-8-8-4's (M-3/M-4)

- Clinchfield's 4-6-6-4's (E-2/E-3)

- Great Northern's 4-6-6-4's (Z-6)

- New York Central's 4-8-4's (Niagara's) and some of its 4-6-4's (J-1a and J-3a)

- Northern Pacific's 4-8-4's (N-5) and 4-6-6-4's (Z-7/Z-8)

- Spokane, Portland & Seattle's 4-6-6-4's (Z-6)

- Union Pacific's 4-8-8-4 "Big Boys," 4-6-6-4's, and some of its 4-8-4's (FEF-2/FEF-3)

A little Pennsylvania 0-4-0, #713 (A5s), with its slope-back tender, appears to be performing switching chores through the streets of Atlantic City, New Jersey on April 25, 1954. Doug Wornom photo.

A little Pennsylvania 0-4-0, #713 (A5s), with its slope-back tender, appears to be performing switching chores through the streets of Atlantic City, New Jersey on April 25, 1954. Doug Wornom photo.Tenderless

There was one locomotive variant that did not use a tender; known as a "tank engine" these designs were equipped with a "U"-shaped water storage device straddling the boiler while a small bunker sat just behind the cab holding coal or oil.

They were typically used in switching operations while some loggers had small compound Mallets (normally 2-6-6-2T's) built in this fashion. They were small and compact but offered plenty of power in moving heavy log trains over stiff grades.

A "T" designation was added to the Whyte notation to differentiate these variants. Today, several tenderless locomotives have been restored to operation including a few Mallets.

Recent Articles

-

Minnesota Father's Day Train Rides: A Complete Guide

May 11, 25 12:16 AM

If you're in Minnesota and looking for a unique way to spend this day with your dad, consider taking a scenic train ride. -

Maine Father's Day Train Rides: A Complete Guide

May 10, 25 11:26 PM

This year for Father's Day, why not trade the conventional gifts and barbeque in for something exceptional—a scenic train ride across the beautiful state of Maine. -

Kentucky Father's Day Train Rides: A Complete Guide

May 09, 25 05:10 PM

Kentucky offers a variety of historic and scenic train excursions that provide an unforgettable way to honor and spend quality time with fathers.