Streetcar History: Lines, Photos, Decline

Last revised: March 2, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Streetcars and trolleys essentially describe the same operation as they are one in the same. The streetcar, which sprang up after the Civil War, was the first rapid-transit system many cities utilized in ferrying residents from one place to another.

They were originally horse or mule-powered and operated at only a few miles-per-hour. Following years of trials, tests, and experiments, Frank J. Sprague came up with a successful design in the 1880's that forever changed electrified streetcar operation.

Electricity was also cheaper, cleaner, and more efficient than animals. As a result, cities and towns across America had placed trolleys in service by the early 20th century.

According to the book, "GE and EMD Locomotives: The Illustrated History" by Brian Solomon, there were more than 850 electrified streetcar systems in service by 1898 and virtually every urban center across the country had at least one of its own.

From the trolley sprang the interurban, a larger operation which linked multiple towns with electrified service.

Unfortunately, they were never built properly to effectively compete against standard steam railroads but, nevertheless, marked the zenith of light-density railroad electrification in the United States. Streetcars would suffer a similar fate as many were gone by World War II.

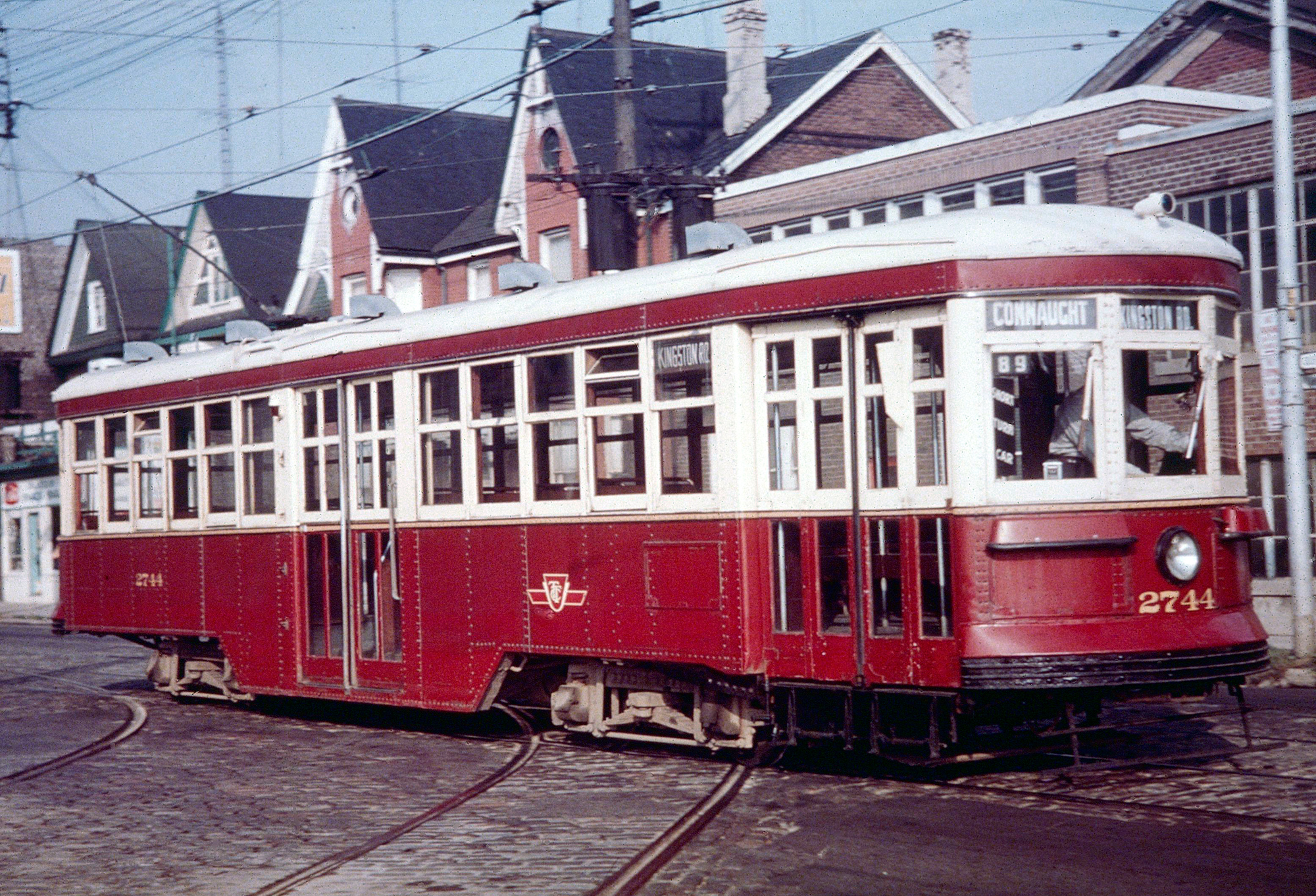

Toronto Transit car #2744 heads towards the Connaught Barn on Queen Street during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Toronto Transit car #2744 heads towards the Connaught Barn on Queen Street during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.The history of streetcars can be traced all of the way back to 1826 when Gilbert Vanderwerken's horse-powered omnibus service launched in Newark, New Jersey.

For the next six decades animals were the preferred, and for all essential purposes, only form of propulsion available.

But the horse had many drawbacks; several were needed to maintain regular, interrupted service (each, at that time, cost between $125 and $200); they required at least 30 pounds of hay/grain daily; and their life expectancy was short.

Unfortunately, even following the development and successful application of steam locomotives this new technology was not ideal for streetcar operation.

Some utilized what were dubbed "steam dummies," small locomotives intended for light density, rapid transit use. However, the contraptions produced considerable soot and debris, like their larger counterparts.

While other technologies were then in development, notably trams, battery powered cars, and cable cars, none were particularly successful on a wide-scale (the latter would find use in some locations, such as San Francisco, where it remains in use today).

Toronto Transit PCC car #4352 is seen here heading east on College Street in front of the University of Toronto's Wallberg Memorial Building. American-Rails.com collection.

Toronto Transit PCC car #4352 is seen here heading east on College Street in front of the University of Toronto's Wallberg Memorial Building. American-Rails.com collection.According to the book, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," by authors Dr. George Hilton and John Due, the first use of an electrically-operated rail vehicle can be traced back to Thomas Davenport, a blacksmith from Vermont.

In 1835 he showcased a battery-powered model train in Boston and Springfield, Massachusetts, giving hope that one day the technology could be applied on a much larger scale.

During 1851 Professor Charles G. Page, who worked for the Smithsonian Institution, tested a full-scale battery-powered car between Washington, D.C. and Bladensburg, Maryland that reached a top speed of 19 mph.

While batteries were a leap forward they still carried serious limitations; due to the very nature of their self-contained power plants they could only operate for short periods of time.

However, when Antonio Pacinotti developed the continuous-current dynamo in 1860 everything changed. His work eventually led to Zenobe Gramme's invention of the generator in 1870 which could be used in commercial applications.

With refinements in motor technology, Werner von Siemens (who helped conceive the self-excitation field magnet), demonstrated a small electric locomotive in Berlin, Germany in 1879. It used third-rail, hauling 20 people at about 8 mph on a 0.3-mile segment of track.

Newark City Subway PCC #23 is seen here in service at Orange Street in Newark, New Jersey during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Newark City Subway PCC #23 is seen here in service at Orange Street in Newark, New Jersey during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.With the basic components now established, the electric locomotive developed rather quickly although some improvements remained, such as an adequate power supply and motor durability for the rigors of everyday service.

In time, these issues were addressed. Back in America, Thomas A. Edison tested a small dynamo-driven electric locomotive in Menlo Park, New Jersey during 1880 but the famous inventor never took his concept further.

In what could be termed the first successful application of electric rail cars for streetcar service took place in 1883 by two different men, Leo Daft in Greenville, New Jersey and Charles J. Van Depoele in Chicago.

Daft carried out trials in several other cities, such as Baltimore and New York. By 1887/1888 he had refined his system to the point cars achieved power via a four-wheel truck which ran along an overhead wire, pulled by a cable.

This so-called troller was later mistakenly called a "trolley," which became the ubiquitous nickname for streetcars.

Van Depoele's system enjoyed more widespread use, which employed a front-mounted pole trolley. It later found service in cities such as Minneapolis, Wheeling, South Bend, and even parts of Canada.

Shaker Heights Rapid Transit PCC #64 is along Shaker Boulevard and Van Aken Boulevard heading west at Shaker Square, Ohio (Cleveland) during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Shaker Heights Rapid Transit PCC #64 is along Shaker Boulevard and Van Aken Boulevard heading west at Shaker Square, Ohio (Cleveland) during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.The modern streetcar, from which the later interurban movement blossomed, is credited to Frank Sprague, a U.S. naval officer who had graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1878.

After his time in service he worked with a pioneer in battery car technology, Professor Moses Farmer, and later apprenticed under Thomas Edison developing electric lights.

Feeling confident in his abilities he founded the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company in 1885, and went on to produce a reliable 500 volt, direct-current motor.

In 1886 he mounted it within a car for the New York Elevated Railway whereby the motor(s) were situated between the axle, along with a trolley pole and multiple-unit control stand.

This gave way to the typical streetcar which became a common sight throughout America. Sprague failed to interest the New York Elevated but others were impressed.

New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) car #932 is on the the St. Charles Avenue line during the 1980s. American-Rails.com collection.

New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) car #932 is on the the St. Charles Avenue line during the 1980s. American-Rails.com collection.He eventually secured a contract in May of 1887 with the Richmond Union Passenger Railway in Virginia to provide cars for its operation.

It opened on February 2, 1888 and proved a phenomenal success. With his single invention, electrified streetcars and trolleys were rapidly laid down throughout the United States.

By 1902, some 15,000 miles were in service across the country (accounting for 97% of all such operations), an astounding jump of 70% in only twelve years.

Baltimore Transit Company PCC #7371 is inbound on Hillen Street at the corner of Colvin Street during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Baltimore Transit Company PCC #7371 is inbound on Hillen Street at the corner of Colvin Street during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.The Northeast contained the densest network of these local streetcar carriers.

While the definitions of, and distinctions between, streetcars and interurbans has always been hazy, the Northeast boasted what are considered true trolleys.

They were local in nature, served only one urban center, and virtually all lines were situated within the street.

By contrast, interurbans connected more than one town and their rights-of-way often either ran alongside a local county road or were privately owned.

Major interurban car manufacturers also produced the same equipment for streetcar lines; names like the Barney & Smith Car Company, Cincinnati Car Company, G.C. Kuhlman Car Company, J.G. Brill Company, Jewett Car Company, Niles Car & Manufacturing Company, St. Louis Car Company.

For instance, Massachusetts contained some 3,056 miles (1917) of streetcar trackage (much of which was situated around Boston), earning it the distinction as the only state to have more electrified railroads than traditional, steam-powered lines.

Unfortunately, the streetcar fared little better than the interurban as the 20th century progressed.

Due to the competition from automobiles and commercial trucks, most were in serious trouble by World War I and few remained by World War II.

Ironically, in recent years the streetcar, now known as light-rail transit systems, have a made a comeback to provide local service within urban environments. To read more about the interurban please click here.

Recent Articles

-

Minnesota Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 22, 25 12:17 PM

The state of Minnesota has always played an important role with the railroad industry, from major cities to agriculture. Today, several museums can be found throughout the state. -

Massachusetts Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 11:41 PM

There are a handful of museums located in the state of Massachusetts detailing its long and storied history with trains, which can be traced back to the industry's earliest days. -

Maryland Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 01:36 PM

The state of Maryland is where it all began with the Baltimore & Ohio. Along with the B&O Railroad Museum, several other similar organizations can be found in the state.