B&O's "Shenandoah" (Train): Consist, Timetable, Photos

Last revised: September 6, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The name Shenandoah has often been associated with the Baltimore & Ohio, from the Shenandoah Valley in which the railroad operated to the train

named after it.

It was first created in the 1930s, renamed from an earlier run and designed to be a less expensive alternative to the B&O's flagship, the Capitol Limited.

Despite its secondary status the Shenandoah was popular, among other reasons, since it hosted transcontinental sleepers within its consist. The train was eventually streamlined and marketed as one of the railroad's premier trains.

As patronage declined during the 1960s the name was dropped but then returned until the start of Amtrak in 1971. The new carrier used the name during the mid-1970s west of Washington, D.C. but eventually discontinued it altogether during the early 1980s.

Photos

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4517 has Train #11, "The Metropolitan" (left) while E9A #1456 is ahead of Train #7, "The Shenandoah" (right) at the railroad's beautiful Queen City Hotel in Cumberland, Maryland on December 5, 1970. By this date the trains ran as one section from Washington, D.C. to Cumberland and then were split into separate sections. Roger Puta photo.

Baltimore & Ohio F7A #4517 has Train #11, "The Metropolitan" (left) while E9A #1456 is ahead of Train #7, "The Shenandoah" (right) at the railroad's beautiful Queen City Hotel in Cumberland, Maryland on December 5, 1970. By this date the trains ran as one section from Washington, D.C. to Cumberland and then were split into separate sections. Roger Puta photo.History

The history of the Shenandoah can be traced back to an earlier B&O train, the Pittsburgh And Chicago Express (westbound, train #9)/Chicago And Pittsburgh Express (eastbound, train

#10), which began during early 1918 (the railroad actually already had

service long-established between the two cities but simply renamed the trains).

During this era when rail travel was at an all-time the B&O hosted a bevy of regional trains like this, particularly between Pittsburgh and Chicago (with many operating via Wheeling, West Virginia).

Following the railroad's entrance into the streamliner craze during the mid-1930s with trains like the Capitol Limited, Royal Blue, and Columbian the B&O began to significantly update its passenger timetable to better reflect the changing times.

For instance, trains #9 and #10 became the Shenandoah after May of 1937, which were later renumbered trains #7, westbound and #8, eastbound (#9 and #10 then became the Chicago-Pittsburgh-Washington Express).

The B&O's new run was extended beyond its former regional status and operated all of the way to the East Coast at Baltimore/Washington, D.C.

The railroad marketed the train to those who could either not afford or did not wish to pay top price to ride the Capitol Limited, while still offering top-level service.

The B&O also timed the train to make sure the westbound leg left D.C. and Pittsburgh overnight and arrived in Chicago during mid-afternoon. This insured that passengers wishing to catch late-afternoon western trains could do so.

Additionally, the eastbound run left Chicago later that night and was then passing through the Appalachian Mountains during midday to allow passengers breathtaking views during the daylight hours.

Aside from the fact that the Shenandoah was popular for its timed western connections at Chicago it also handled a large amount of mail and express within its consist.

Interestingly, it remained a steam-powered, heavyweight train until after the end of World War II. With more money to spend the B&O upgraded its top passenger trains during 1945 acquiring either new streamlined equipment from Pullman-Standard or building its own at its Mount Clare Shops. This effort saw trains like the Capitol Limited, Columbian, National Limited, Cincinnatian, and Shenandoah all reequipped.

The railroad also purchased second-hand, light-weight cars from other lines, notably the Chesapeake & Ohio including three dome-sleepers.

Of these, the Capitol Limited received two while the Shenandoah was given one, which first debuted on April 13, 1950 between Chicago and Pittsburgh.

It normally operated every other day, going west and then returning east. Interestingly, as the secondary run for the Cap when the flagship's dome-sleeper was out-of-service for standard maintenance the Shenandoah's replaced it so sometimes the train would operate for many weeks without sleeper service available.

Overall, the train's consist mostly included coaches along with a diner, buffet-solarium lounge (the only of its kind ever operated), and aforementioned dome-sleeper. Except for the sleeper, while streamlined all of the cars were rebuilt from older heavyweights.

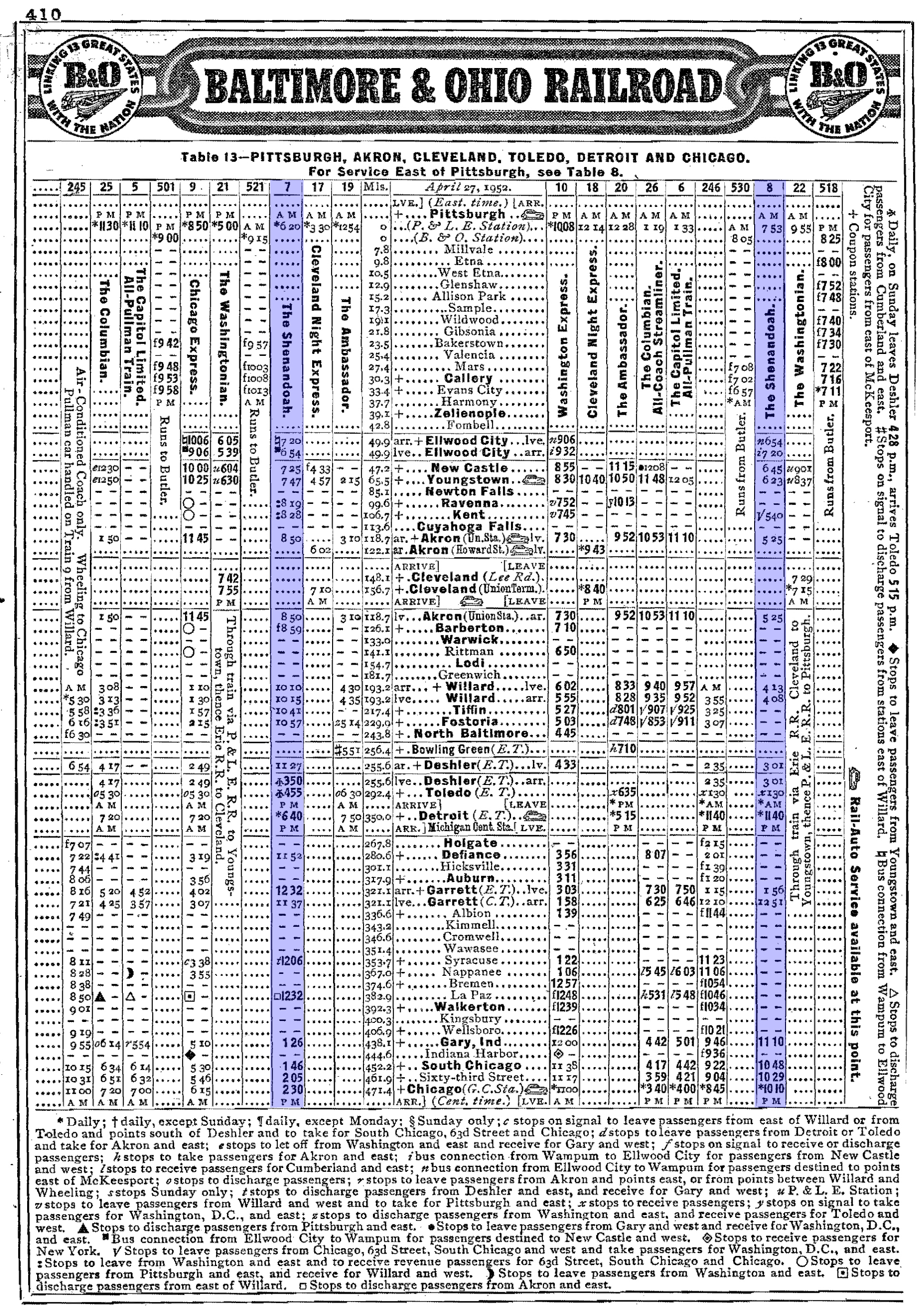

Consist (1952)

During the late 1940s the Shenandoah finally received diesel power in the form of E7As (first acquired in 1945) as the B&O continued upgrading its fleet with more new locomotives such as E8As/Bs and F3As/Bs (some of which were assigned to passenger service, notably the Columbian).

While the B&O may not have been as rich as the Pennsylvania or as glamorous it nonetheless offered only the very best service.

Take for instance, the Shenandoah, which may have been a secondary train but offered first class amenities including stewardess-nurses that tended to a passengers every need.

Unfortunately, all of these great services could not stem increasing losses after the war. During 1948 the B&O offered some 185 different trains across its network according to Craig Sanders' book Limiteds, Locals, And Expresses In Indiana, 1971.

However, this number had dropped to 98 by July of 1956 and continued to fall throughout the rest of the decade. As for the Shenandoah it lost its dome-sleeper after October 27, 1963.

Additional cutbacks had already preceded this, however, when it lost its buffet-solarium lounge on October 30, 1960 and began terminating only to Washington, D.C. during the fall of 1962. During that decade the train had begun receiving more head-end, mail/express as other less-noteworthy runs were dropped from the timetable.

While this improved the train's financial performance it slowed its schedule. During 1964 the B&O changed the train's name to the Diplomat (once, a well-known train itself that served St. Louis) but then in an interesting move brought back the Shenandoah name; first, in 1968 the eastbound run returned between Pittsburgh-Washington, and then in 1970 the train was reinstated entirely between Pittsburgh-Chicago.

Timetable (1952)

As for the B&O the railroad was very passionate about its passenger services. Unfortunately, the severe losses incurred simply forced its hand. For instance, as early as 1950 passenger revenues were only 5% of the B&O's gross revenues but accounted for 47.5% of deficits on freight's net income.

The year 1970 also witnessed the Shenandoah truncated to only a Akron - Washington, D.C. routing although it survived in this capacity until the start of Amtrak on May 1, 1971.

Incredibly, the new national carrier brought back the name for a few years beginning in October of 1976 running between Washington and Cincinnati (the same route as the former Cincinnatian) along the B&O's now-abandoned St. Louis main line. However, this version survived only until 1980 due to lack of ticket sales.

Amtrak

One of Amtrak's more scenic trains to skirt the Appalachian Mountains was its Shenandoah, which operated between Washington, D.C. and Cincinnati.

The idea for the train was actually thanks to a senator from West Virginia who hoped to see rail service restored across the Mountain State, which had once been provided to both the northern and southern regions.

Thanks to his efforts Amtrak began to serve both areas including a forerunner to the Shenandoah as well as the Cardinal along the New River Gorge.

For nearly a decade the national carrier tried to make things work for the northern corridor although just as predecessor Baltimore & Ohio had experienced a lightly populated region made ridership numbers difficult to both gain and sustain.

Ultimately, Amtrak pulled the plug on the route in the early 1980s and a few years later much of the line was shortsightedly abandoned by Chessie System/CSX Transportation.

During the first few years of Amtrak's operations the carrier actually experimented with several trains using the B&O's main line from Baltimore/Washington, D.C. to St. Louis. This route headed west to Cumberland where it continued due southwest to Grafton, West Virginia.

From there it wound its way through the Mountain State's northern foothills with the largest cities along the corridor at Clarksburg and Parkersburg, the latter of which lay along the Ohio River.

Crossing over into Ohio the line reached the small college town of Athens, then on to Chillicothe and Greenfield before connecting to Cincinnati. From there it continued westward through southern Indiana and Illinois before reaching St. Louis.

For decades it was a key route for the B&O, both in terms of passenger trains like the National Limited and expedited freight movements, especially from the 1960s onwards when the route was heavily upgraded through West Virginia to raise tunnel heights for COFC (Container On Flat Car) and TOFC (Trailer On Flat Car) traffic.

By the early 1970s this was still an important source of revenue for the railroad. However, after Amtrak took over intercity passenger responsibilities on May 1, 1971 it initially ended scheduled trains over the route. The B&O's final service over the route ended a day before on April 30th with the National Limited.

However, thanks to democratic congressman Harley Orrin Staggers, the future brainchild behind the Staggers Act which would deregulate the industry in 1980 the loss of passenger rail service to the Mountain State was short-lived.

In September, 1971 Amtrak launched the West Virginian between Washington, D.C. and Parkersburg. Interestingly, the B&O had operated a train of the very same name between Jersey City, New Jersey (New York City, as the B&O liked to proclaim) and Parkersburg listed as trains #23 and #24.

It was a dayliner that served the 351-mile corridor for many years although lack of ridership eventually forced the B&O to merge it with the Cleveland Night Express in 1954 and tried to increase patronage by extending it to Cincinnati.

New equipment was even purchased in 1962 but eventually the railroad gave up on the train with its last run occurring on July 4, 1964.

Amtrak's version, which also became known as Harley's Hornet or the Staggers Special because of the congressman's influence, also had trouble attracting ridership (it did not help that around the time the train was introduced the city of Parkersburg razed their beautiful, two-story Sixth Street Station in place of a parking lot).

Interestingly, in 1972 in an attempt to gain attention and passengers Amtrak experimented by rerouting its high speed UAC Turbo Train along the line and renaming it as the Potomac Turbo.

The trainset later became known as the Potomac Special but unfortunately, mechanical issues and a lack of ridership saw Amtrak pull it from service on April 29, 1973.

In its place the carrier inaugurated the regional Blue Ridge from Baltimore/Washington to Martinsburg and while it was later canceled the route is still served today by commuter line MARC Train.

Surprisingly, this was not the end of passenger service over the route. On October 31, 1976 Amtrak again inaugurated a train between Baltimore/Washington and Cincinnati known as the Shenandoah.

From Cincinnati passengers had the opportunity to catch a connecting train to Chicago via the James Whitcomb Riley/Mountaineer, later renamed the Cardinal in 1977 and operated to Newport News, Virginia.

By the late 1970s Amtrak had acquired enough new equipment that the Shenandoah's consist usually included Amfleet cars and either a GE P30CH or EMD F40PH for power.

Accommodations on board, since it was only a short run of under 300 miles, only included coaches and a café/snack car. However, due to complaints Amtrak began offer makeshift sleeping accommodations known as Ampads at the ends of coaches.

Baltimore & Ohio E9A #1455 (built as #36) and GP7 #6693 have what remains of train #8, the eastbound "Shenandoah," near Washington, D.C. in May, 1968. Author's collection.

Baltimore & Ohio E9A #1455 (built as #36) and GP7 #6693 have what remains of train #8, the eastbound "Shenandoah," near Washington, D.C. in May, 1968. Author's collection.Final Years

In 1979 congressional budget cuts forced Amtrak to reduce its network, particularly those trains that saw the lowest ridership.

As one of its worst performing routes, Amtrak was quick to cut the Shenandoah in 1980. The train made its final run September 30, 1981. The eastern leg of the route was picked up by the Capitol Limited (Cumberland-Baltimore/Washington).

Sadly, the hope of riding a train through northern West Virginia and southern Ohio was no longer an option after 1985 when CSX/Chessie System oddly elected to abandon the route between Clarksburg and Cincinnati citing high maintenance and low traffic.

Today, the Mountain State section of this line is now a

rail/trail while the Ohio portion is mostly an overgrown path save for a

few sections that remain in use by short lines.

Recent Articles

-

Nevada - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 28, 25 03:26 PM

While it may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of wine, you can sip this delight by train in Nevada at the Nevada Northern Railway. -

New Hampshire - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 28, 25 03:22 PM

This article details New Hampshire's most enchanting wine tasting trains, where every sip is paired with breathtaking views and a touch of adventure. -

Virginia - Murder Mystery - Dinner Train Rides

Dec 28, 25 12:23 PM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel.