Rutland Railroad: "The Green Mountain Gateway"

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Rutland Railroad (later Railway) was a fabled system located in the New England area. Based out of Rutland, Vermont it is perhaps best remembered for the large amount of milk and dairy

products it moved over its system and its classic forest green and yellow

livery.

The Rutland can trace its roots to the vision of Timothy Follett. Throughout the railroad's many years of operation it was seemingly always in financial straits.

The railroad finally succumbed to its long battle of money troubles in the early 1960s when a strike, and declining revenues, collapsed any hope of the Rutland staying solvent.

Today, happily, a large segment of the former system is still operated by successor Green Mountain Railroad/Vermont Railway.

These two roads haul both freight and excursion passenger trains over the remaining system, much to the delight of the thousands of passengers which arrive annually to enjoy the state's incredible scenery.

Photos

Former Rutland RS3's at Louisville, Kentucky following their sale to the Louisville & Nashville on April 4, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.

Former Rutland RS3's at Louisville, Kentucky following their sale to the Louisville & Nashville on April 4, 1963. American-Rails.com collection.History

While Vermont was home to such classic carriers as the Boston & Maine, Central Vermont, Delaware & Hudson, and even the Maine Central the Rutland carried perhaps the most charm of all and many Vermonters certainly identified with it as "their" railroad.

The system has its beginnings dating back to the Champlain & Connecticut River Rail Road, which was chartered by the State of Vermont in during October of 1843 to connect Rutland and Burlington.

The C&CR was the vision of Timothy Follett, who already owned a steamship business on Lake Champlain.

He believed that a railroad running from the Connecticut River, following the Williams River towards the west, linking to Mt. Holly, and then heading north through Rutland and connected to Burlington along the lake would be a successful operation.

At A Glance

Bellows Falls, Vermont - Rutland - Burlington - Rouses Point, New York Rouses Point - Ogdensburg, New York Alburgh, Vermont - Noyan, Quebec Rutland - Bennington, Vermont Bennington, Vermont - Chatham, New York Leicester Junction - Larrabee's Point, Vermont | |

At the same the General Assembly also gave charter to the Vermont Central Railroad, organized by Charles Paine. This line was to utilize a more northerly route through the White and Onion River valleys while passing through Northfield (his hometown).

These two individuals grew into bitter rivals and the railroads they built similarly remained at odds with one another for many decades.

During November of 1847, Follett renamed his system as the Rutland & Burlington Railroad to better reflect his intentions.

Over the next two years Follett worked hard in seeing the R&B brought to completion; in 1849 construction picked up and was finished by the fall of that year between Bellows Falls and Burlington.

To capstone the project, a race was held to see whether a team of horses or a train could move the mail faster between the two cities. The train won by a good two hours!

Rutland RS3 #203 crosses the northern islands of Lake Champlain (South Hero, Grand Isle, and North Hero) via its marble, riprap causeway with what appears to be a milk train during the 1950s. Today, the right-of-way is the Island Line Rail Trail. Tom Stewart photo.

Rutland RS3 #203 crosses the northern islands of Lake Champlain (South Hero, Grand Isle, and North Hero) via its marble, riprap causeway with what appears to be a milk train during the 1950s. Today, the right-of-way is the Island Line Rail Trail. Tom Stewart photo.Financial difficulties first began appearing in the 1860s; traffic had not materialized (as Jim Shaughnessy notes in his book, "The Rutland Road: Second Edition" it was a system that connected "nowhere to nowhere") in part due to the fighting with Paine's Vermont Central which refused to offer interchange.

Expansion

On July 9, 1867 the bankrupt R&B was reorganized the Rutland Railroad Company. Under the direction of John Page efforts were made to gain new and permanent interchange partners:

- The Cheshire Railroad (later Boston & Maine) was secured at Bellows Falls.

- Cross-lake traffic at Burlington was gained via the Whitehall & Plattsburgh across the waters at Plattsburgh (this road was attempting to provide its own northerly connection into Canada).

- A western connection was also acquired with the Rensselaer & Saratoga at Rutland.

During 1870 the Rutland expanded its system exponentially, gaining new western and southern outlets by leasing the Whitehall & Plattsburgh as well as the Vermont & Massachusetts (neither road was ultimately folded into its system).

It also picked up the small Addison Railroad giving it access to Ticonderoga, New York and grew its steamship freight business via control of the Champlain Transportation Company.

A nervous Vermont Central leased the Rutland on December 30, 1870 in an attempt to quell the growing competition from its biggest competitor.

Unfortunately, this move eventually forced the VC into bankruptcy during March of 1896 and the Rutland regained its independence on May 7th of that year. The old adversaries may have ended their longtime feud but the Rutland continued to grow into the 20th century.

Logo

On September 27, 1901 it formally took over the Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain, given it access to Ogdensburg along the shores of the St. Lawrence River and connections with the Rome, Watertown & New York at Norwood (later New York Central) and the Adirondack & St. Lawrence at Malone (also later part of NYC).

The O&LC did not provide considerable online freight, aside from interchange traffic but it would later prove a solid generator of agricultural traffic (notably milk) and Ogdensburg became a vital port in shipping goods to and from Chicago over the Great Lakes.

Just prior to this event was Rutland's efforts to provide itself a direction connection with the O&LC. To do so required bridging the gap between Rouses Point, New York and Burlington, which meant incorporating a new company.

The new system was known as the Rutland & Canadian, completed in 1899. Its right-of-way was an impressive display of engineering.

The railroad leap-frogged the northern islands of Lake Champlain at South Hero, Grand Isle, and North Hero using a marble, rip-rapped causeway to reach Alburgh before briefly crossing the waters again to connect with Rouses Point and the O&LC.

The 40 miles of new line were completed in only a year and were consolidated into the Rutland during January of 1901. Amazingly, this wasn't the final addition to the railroad's system that year. On June 1st it also picked up the Chatham & Lebanon Valley, part of the fabled "Corkscrew Division."

The C&LV, along with the Bennington & Rutland (acquired in February of 1900 this road operated between Rutland and Bennington), gave the Rutland a through route to Chatham, New York.

System Map (1940)

Both lines comprised the Chatham Division, a winding, circuitous route complete with 263 curves. While it provided the Rutland with southern interchange to the NYC it was an operational headache.

With these leased lines added to the Rutland's system it had reached its farthest extent, operating just over 400 miles of railroad on a system that looked a bit like an upside-down “L” between Chatham, New York to Alburgh, Vermont with a western extension from Alburgh to Ogdensburgh, New York.

The railroad’s one major "branch" was its original main line, extending from Rutland southeasterly to Bellows Falls where it connected with the B&M.

For all of the fondness and status surrounding the Rutland, particularly by the people of Vermont, the railroad continued to struggle for most of its life; the road simply served no major online customers or manufacturing centers (its most notable freight over the years included marble, milk, and lumber).

It again fell under the control of an outside railroad when the New York Central gained control in 1904, which went on to sell half its interest to the New Haven Railroad in 1911.

New troubles arose in 1915 when the Panama Canal Act forced the Rutland to divest itself of the Rutland Transit Company, a steamship operation that cost it valuable interchange traffic from Chicago over the Great Lakes. The years under NYC control arguably witnessed one of the last great periods of prosperity.

The Central moved a large amount of bridge traffic over the Rutland to transfer through Ogdensburg and paid for infrastructure and equipment upgrades. Alas, these good years would not last. Following the Panama Canal Act the Central dropped much of its interest and control in the railroad.

This wonderful scene depicts Rutland's yard and terminal in its home city of Rutland, Vermont looking north. The date is not listed but the photo was likely taken during the late 1940's or early 1950's. American-Rails.com collection.

This wonderful scene depicts Rutland's yard and terminal in its home city of Rutland, Vermont looking north. The date is not listed but the photo was likely taken during the late 1940's or early 1950's. American-Rails.com collection.Together both it and the New Haven owned 52% of the railroad’s common stock until 1941 when they sold their interest altogether.

The 1920s were another time of relatively strong traffic with the rise in lucrative milk shipments and other freight. However, again, these happy times were short-lived.

Things took a turn for the worse in 1927 when major flooding in Vermont heavily damaged large sections of the Rutland’s right-of-way (more than half its total mileage!).

Then, in May of 1938 the railroad entered receivership and was on the verge of total shutdown until the unions agreed to a wage reduction in August that kept the railroad operating.

Additionally, state and local governments, as well as the people of Vermont, worked to keep the company operational by donating money (such as the "Save The Rutland Club) and reducing its tax burden (some bills were forgiven altogether).

One notable means the road implemented to increase tonnage was the launching of "The Whippet," a high-speed, timed freight train which ran the length of the system hauling bridge traffic.

A 2-8-0 Consolidation was even painted black and silver to advertise the service along with print media making potential customers aware of the program.

It largely worked, and the company also picked up some less-than-carload freight in the process, although the train lost its name with the start of World War II.

After the war the Rutland was in trouble again (having already reorganized in November of 1950 to become the Rutland Railway, bringing a new logo and image, "The Green Mountain Gateway"), this time with a strike as the railroad’s organized workers would not comply with a new change in operational practices.

New management, led by Gardner Caverly after 1954, did everything they could to reduce losses and pull the company out of its perennial red ink.

Some of these efforts included:

- Scrapping the entire steam fleet (58 locomotives in all, including its four new 4-8-2s purchased in 1946) for fifteen new diesel road-switchers from Alco (RS1s and RS3s) in 1951-1952

- Abandoning the Chatham Branch in 1953 (57 miles in all).

- Cutting the workforce from nearly 1,200 employees to just 400.

- Purchasing several hundred new freight cars from Pullman-Standard allowing it to scrap its tired fleet of rolling stock (a lot of which would be accepted by interchange partners).

The strike came down on June 26, 1953, first in the company's long history, and ultimately led to the cessation of all passenger operations.

After 21 days management and labor were able to reach an agreement and the railroad to resume all operations, sans the money-losing passenger trains.

Unfortunately, all efforts to streamline operations could not curb the growing loss of its freight traffic.

The once lucrative milk trains had all but disappeared (taken away by trucks) and it was becoming increasingly difficult for management to find ways in keeping the company even marginally profitable.

By the mid-1950s there were about 331 miles left of the original system and good management had allowed for one final brief period of relatively good years late during the decade. However, as the 1960s dawned its ghosts returned to doom the company.

As traffic continued to slide away a point was reached whereby the company had little place else to trim its losses except to the work rules, and Rutland's remaining employees were already receiving pay below the national average.

To help ease the losses and improve efficiency new company president William Ginsburg proposed reducing its subdivisions from three to only two, allowing trains to operate further and faster.

The old operations had long called for trains to operate between either Bellows Falls-Rutland or Bennington-Rutland, Alburgh-Rutland, and Alburgh-Ogdensburg.

The new divisions would have trains meet at Burlington and run north or south from that point.

More Reading

The Whippet: (Fast freight service between New England and Chicago.)

Chatham Division, The "Corkscrew"

Passenger Trains

Green Mountain Flyer: (New York/Boston - Montreal)

Mount Royal: (New York/Boston - Montreal)

1960 Labor Strike

This issue, naturally, was not satisfactory to the unions and this time they would not relent, walking out on September 15, 1960. A cooling off period was invoked for a year but this did nothing to relieve the stalemate.

As Mr. Shaughnessy notes in his book part of the issue was in regards to the Rutland's now younger workforce, many of whom were not around during the struggles to keep the company operational during the 1930s and earlier.

Many from the older generation, who had often been willing (certainly with some consternation) to take pay cuts for the greater good, had since retired.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS1 | 400-405 | 1951 | 6 |

| RS3 | 200-208 | 1951-1952 | 9 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70-Tonner | 500 | 1951 | 1 |

Steam Roster (Post 1913)

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| B-2/a/b/c, B-3, B-9 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| C-25, C-28, C-29, C-2, C-X | American | 4-4-0 |

| E-1-d, E-14, E-17 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| F-2 Through F-12 (Various) | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| G-14, G-34a/b/c/d | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| H-6a | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| K-1, K-2 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| L-1 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| U-3 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

Shutdown

For nearly two years after the cooling off period had not brought about an agreement, the property sat dormant as rails rusted over and Mother Nature reclaimed what was rightfully hers.

This time, nothing or no one could save the Rutland and the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled for total abandonment on January 29th, 1963. Even after this time the battle continued as union's fought to appeal the ruling and keep the company operational.

These efforts ultimately failed but in an ironic twist of fate, it was announced during mid-June of 1963 that the unions and company had reached an agreement, albeit far too late to the save the Rutland.

Thankfully, in a proactive move during August of 1963 Vermont purchased the former property from Bennington to Burlington as well as part of the Bellows Falls line creating today's Vermont Railway.

Rutland 4-6-2 #84 (K-2) appears to be moving slowly in reverse, perhaps heading towards its train, at the station in Rutland, Vermont in 1951. The railroad's three K-2's were all retired by 1953. Ralph Phillips photo.

Rutland 4-6-2 #84 (K-2) appears to be moving slowly in reverse, perhaps heading towards its train, at the station in Rutland, Vermont in 1951. The railroad's three K-2's were all retired by 1953. Ralph Phillips photo.Postscript

The rest, including the entirety of the O&LC as well as the Burlington-Alburgh extension across the lake, was abandoned. Following the shutdown of the Rutland in it was resurrected just a few years later in 1964.

That year F. Nelson Blount created the Green Mountain Railroad. Using a forest green and yellow livery inspired directly from the Rutland (it’s virtually identical) the Green Mountain was started by Mr. Blount to operate his collection of steam locomotives.

While Mr. Blount passed away a few years after creating his new tourist railroad (which eventually became part of the National Park Service’s Steamtown, USA located in Scranton, Pennsylvania) the Green Mountain Railroad lived on and split off as its own operation.

Today, the railroad hauls both passengers and has been widely acclaimed as the top tourist railroad in New England with its spectacular views of Vermont's Green Mountain Range and on board train services.

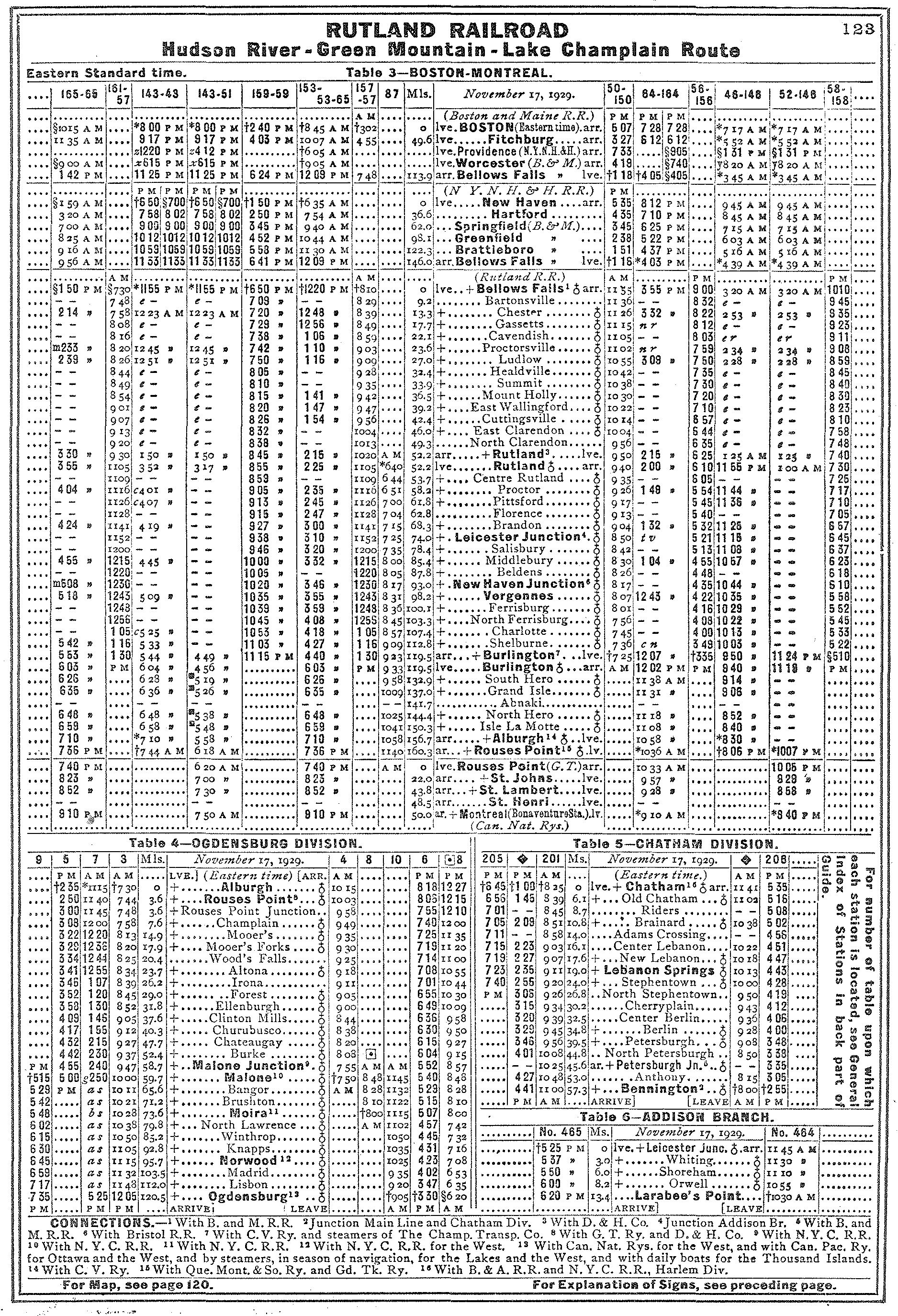

Public Timetables (January, 1930)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Illinois Rails: Journey Through Breathtaking Scenery!

Feb 22, 25 12:33 AM

While the state has many museums there are just a few Illinois train rides available. The two most well known are the Silver Creek & Stephenson and Illinois Railway Museum. -

Wilderness By Train Through Idaho!

Feb 22, 25 12:30 AM

Presented here is a brief guide to available train rides and railroad attractions in the state of Idaho. -

Discover Pennsylvania's Hidden Beauty By Rail

Feb 22, 25 12:23 AM

Pennsylvania train rides offer the greatest collection anywhere in the country except perhaps California. The state has a rich and long-standing history with railroads dating back to the 1820s. To lea…