Civil War Railroads: Map and Facts (North vs South)

Last revised: October 27, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Railroads in the Civil War would play a pivotal role in deciding how the campaign transpired. The North not only held a commanding advantage in total mileage but also boasted a mighty industrial machine across New England.

There were many reasons for the South's failure to achieve victory. One of the most noteworthy was its inability to properly utilize the railroad.

It also faced an unforeseen problem of suffering tremendous damage from Union forces which were successful in regularly disrupting operations.

Since most of the fighting occurred below the Mason-Dixon Line this issue was only magnified as the conflict wore on. For its part, the North suffered setbacks as well. Most notably was the venerable Baltimore & Ohio which lay in the heart of the fighting.

History and Facts

Initially, the B&O was an ardent Southern sympathizer but that changed after a series of Confederate attacks severely crippled its network.

As Mike Schafer notes in his book, "Classic American Railroads," it proved an invaluable asset for the Union.

Aside from the war railroads dealt with other issues throughout the 1860's, such as numerous track gauges and a lack of sufficient bridges spanning major waterways. Issues like these resulted in a lack of fluidity.

Photos

Mortar technology was not new during the Civil War but making it mobile was, as seen here with the "Dictator" near Petersburg, Virginia in 1864.

Mortar technology was not new during the Civil War but making it mobile was, as seen here with the "Dictator" near Petersburg, Virginia in 1864.Union vs Confederacy

When discussing railroads during the Civil War their role is often overlooked. They proved a vital asset in the movement of troops and materiel, ultimately allowing the North to achieve total victory. After fighting broke out in 1861 the country had a rail network totaling more than 30,000 miles.

Of this, 21,300 miles (along with 45,000 miles of telegraph wire), or about 70%, was concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest while the Confederacy enjoyed only 9,022 miles (and 5,000 miles of telegraph wire).

Despite this discrepancy the South did command one advantage; most of its trackage was brand new at the time.

As William Thomas points out in his book, "The Iron Way: Railroads, The Civil War, And The Making Of Modern America," 75% of its lines had been constructed only in the 1850s.

The railroad may have still been a relatively new technology during the mid-19th century but the need for heavier rail, reinforced bridges, and durable rights-of-way to handle ever-increasing tonnage had become well understood by that time.

A long, roughly 4x4 block of wood which was bolted into adjacent ties and situated firmly against the outside rail offered a quick repair to a damaged or broken track. In this way it continued offering a guideway for the wheel and flange while also supporting the rail until a permanent fix could be carried out. American-Rails.com collection.

A long, roughly 4x4 block of wood which was bolted into adjacent ties and situated firmly against the outside rail offered a quick repair to a damaged or broken track. In this way it continued offering a guideway for the wheel and flange while also supporting the rail until a permanent fix could be carried out. American-Rails.com collection.The Confederacy's lack of such infrastructure was further compounded by its inability to effectively harness the iron horse for military purposes as historian John P. Hankey articulately points out in his excellent essay from the March, 2011 issue of Trains Magazine entitled, "The Railroad War: How The Iron Road Changed The American Civil War."

For instance, Southern leaders believed civilian rail movements should take precedence over military transports.

It was not until the war's final years did the Confederacy understand the railroad's usefulness. In contrast, by 1862 the North began laying the groundwork for what became a unified and efficient transportation network.

It began with President Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Pacific Railway Act into law on July 1, 1862, authorizing construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.

The project was launched within a year and formally completed on May 10, 1869 when Union Pacific and Central Pacific met at Promontory Summit, Utah.

The idea for such a coast-to-coast railroad dated back to 1854-1855 when then-Secretary of War Jefferson Davis led surveying efforts west of the Mississippi River.

Mr. Thomas goes on to note that leaders in the North viewed railroads a bit differently than their Southern counterparts. While both understood their importance, the South saw trains as a means of maintaining slavery's status quo for economic growth.

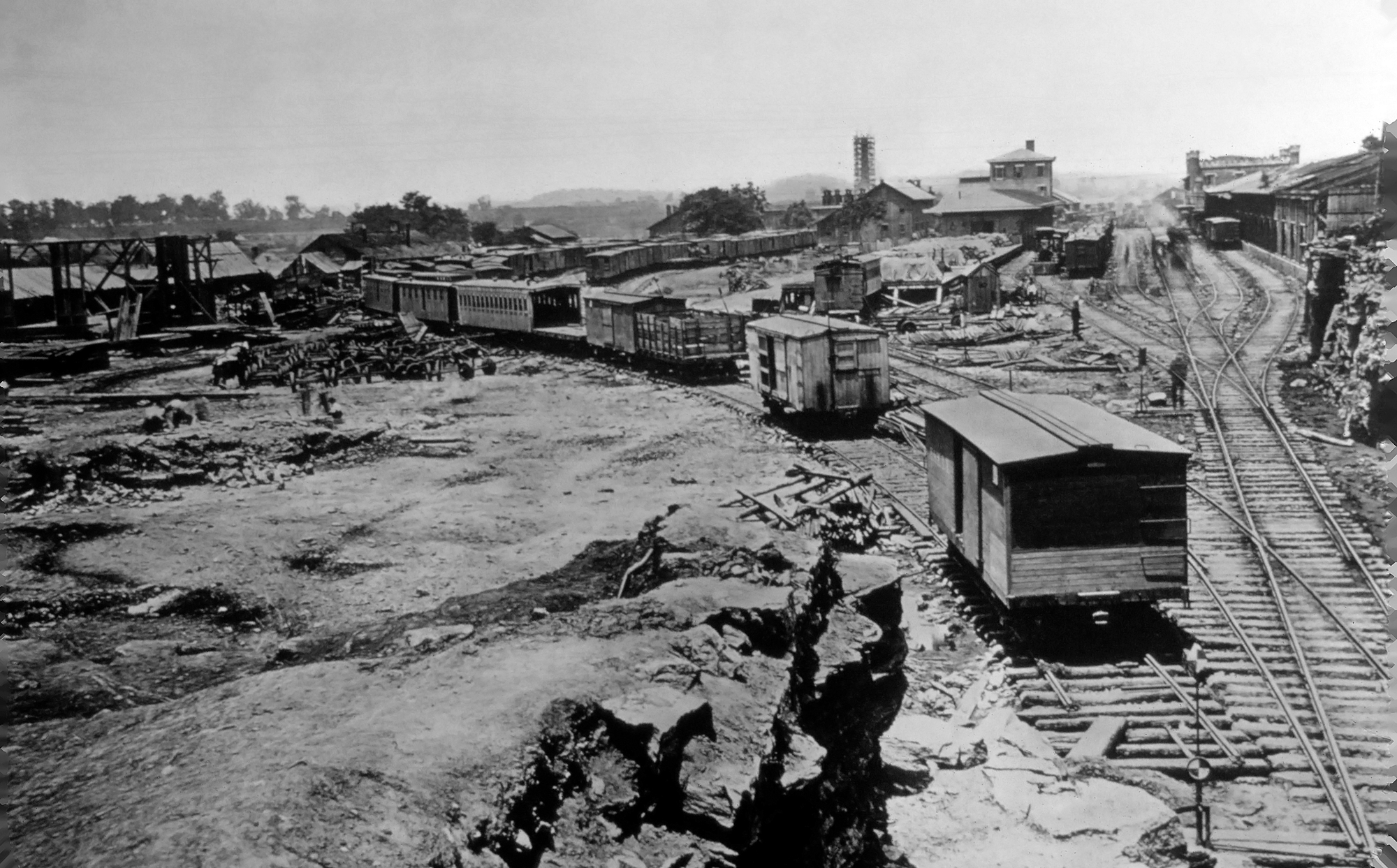

The Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad's yard and station in Nashville, Tennessee as it appeared in March, 1864. American-Rails.com collection.

The Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad's yard and station in Nashville, Tennessee as it appeared in March, 1864. American-Rails.com collection.By comparison, the North employed them as a means of developing new territories for trade and economic prosperity, which led to the Transcontinental Railroad's creation. There were four potential routes chosen; a northern, central, and two southern corridors.

Unfortunately, none could satisfy parities both for, and against, slavery and the plan was shelved. However, once the war broke out, states seceded, and Davis became President of the Confederate State of America, the Union was free to do as it wished.

A view of Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania during November, 1863. It has been stated the individual in the background with the top hat may be President Abraham Lincoln on his way to deliver the famous Gettysburg Address although this has never been proven. Today, the station and tracks are still in use. American-Rails.com collection.

A view of Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania during November, 1863. It has been stated the individual in the background with the top hat may be President Abraham Lincoln on his way to deliver the famous Gettysburg Address although this has never been proven. Today, the station and tracks are still in use. American-Rails.com collection.Northern leaders subsequently settled on the central route which was projected to run due west of the Missouri River at Omaha, Nebraska/Council Bluffs, Iowa and terminate at San Francisco.

While Union Pacific's and Central Pacific's project is best remembered it was not the only transcontinental project undertaken at that time.

On July 2, 1864 President Lincoln signed an updated Pacific Railroad Act into law which created the Northern Pacific Railroad Company to build a northern route into the Pacific Northwest.

The NP was dealt a series of logistical and financial problems that delayed its completion by nearly two decades.

However, once finished it too was instrumental in opening another segment of the country to economic growth. In time, three other systems reached Puget Sound; Union Pacific, Great Northern, and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific (Milwaukee Road).

The United States Military Railroad (Union Army) carries out right-of-way repair on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad near Aquia Creek outside of Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1863. The USMR was a vital asset to the North's war strategy. American-Rails.com collection.

The United States Military Railroad (Union Army) carries out right-of-way repair on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad near Aquia Creek outside of Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1863. The USMR was a vital asset to the North's war strategy. American-Rails.com collection.The original Pacific Railway Act was not the only important event of 1862; that year also witnessed creation of the United States Military Railroad.

The USMR did not take direct command of the North's rail network (Unlike a half-century later when the United State Railroad Administration operated the nation's railroads during World War I from 1917 to 1920.).

Instead, it acted as its own enterprise and made use of trackage when needed to offer the best tactical advantage. The North fully understood the railroad's importance and mobility. As Mr. Hankey notes virtually all major conflicts were located either at or near important rail junctions.

The USMR was under the command of General Daniel C. McCallum (former general manager of the Erie Railway) and General Herman Haupt (former chief engineer of the Pennsylvania Railroad).

These expert railroaders were incredibly effective at putting together a skilled workforce to maintain efficient operation. The two men were also adept at preventing field officers from interrupting everyday affairs through either meddling or special requests.

Maps

The maps featured here are historic items produced during or just after the war and housed at the Library of Congress.

The first was the work of James T. Lloyd in 1861 depicting all railroads in operation at that time; the second was authored by Julius Bien in 1866 and highlights those rail lines requisitioned by the United States Military Railroad throughout the war. Note that General McCallum's name is prominently displayed on this map.

As previously mentioned, for the significant damage Southern railroads received the B&O was also hit hard since its main line was situated right along Union and Confederate lines within the border states of Maryland and Virginia (West Virginia after 1863).

John Stover notes in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," the B&O rescinded its Southern support when Confederate militia, under the command of then-Colonel Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, laid siege to its line through Northern Virginia. He believed that by crippling B&O's network the Union could not effectively wage war.

While this tactic was unsuccessful the Confederacy did cause more than $2.5 million in damages (over $35 million in today's dollars) which required 10 months to repair. In an attempt to curb further property destruction the railroad built the first-ever armored rail car.

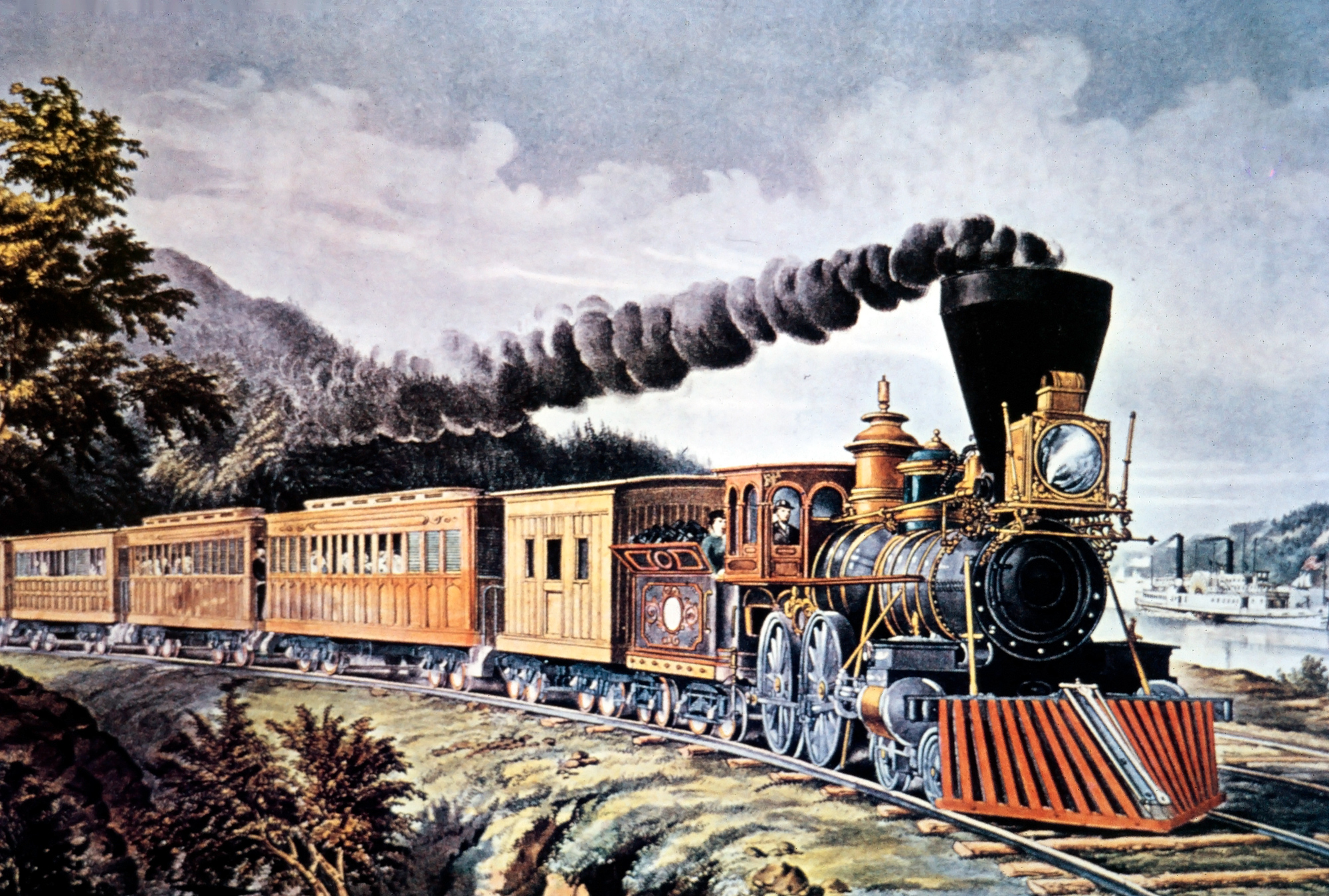

"Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, And The Chattanooga Rail Road." This 1866 lithograph from Currier & Ives features a Nashville & Chattanooga Railway train running along the Tennessee River near Chattanooga. The railroad later became the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis, a future component of the Louisville & Nashville. American-Rails.com collection.

"Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, And The Chattanooga Rail Road." This 1866 lithograph from Currier & Ives features a Nashville & Chattanooga Railway train running along the Tennessee River near Chattanooga. The railroad later became the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis, a future component of the Louisville & Nashville. American-Rails.com collection.It looked quite similar to the South's famous Merrimack ironclad warship except that it rode on wheels!

Interestingly it was the very B&O that initially proved the railroad's tactical effectiveness; on June 2, 1861, more than a month prior to the war's first major engagement at the "First Battle of Bull Run" (known within the Confederacy as the "Battle of First Manassas") it transported troops from Grafton, Virginia to a location about six miles east of the city to capture the town of Philippi ("Battle of Philippi").

The speed of the movement caught Southern forces off-guard, demonstrating just what the railroad could do.

A view of Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania during November of 1863. Today, the station and tracks are still in use.

A view of Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania during November of 1863. Today, the station and tracks are still in use.For the Union's many successes the South enjoy its own triumphs with this technology. There was the previously mentioned "Battle of First Manassas" when General Joe Johnston used the Manassas Gap Railroad to move his troops into position, eventually securing a Confederate victory.

Also, the "Battle of Chickamauga" in early September of 1863 saw a Southern victory after General James Longstreet quickly moved his force of 12,000 men from Virginia to Georgia, which bolstered Confederate lines as part of the Army of Tennessee. Thanks in large part to this effort U.S. forces were defeated after three days of fighting.

More often than not it, however, it was military strategy and not the railroad which led to Southern victory. With a belief in unilateral states' rights there was no central oversight or management of its network. By the time leaders realized this fallacy all hopes for total victory had, to a greater extent, been lost.

"American Express Train." An 1864 lithograph by Currier & Ives. It was also featured on the front cover of the book, "Railroads In The Days Of Steam," published in 1960. American-Rails.com collection.

"American Express Train." An 1864 lithograph by Currier & Ives. It was also featured on the front cover of the book, "Railroads In The Days Of Steam," published in 1960. American-Rails.com collection.Perhaps the most famous railroading event of the war took place in the South, best remembered as the Great Locomotive Chase. It all began in April of 1862 when disguised Union soldiers stole the General, a Western & Atlantic 4-4-0 "American Type" steamer in an attempt to destroy Confederate supply lines.

Also known as the "Andrews Raid" it began at Marietta, Georgia and lasted for nearly 91 miles until a Confederate crew caught up with the locomotive near Ringgold. During the chase the Southerners used a hand-powered track car as well as the locomotives Yonah, Shorter and Texas before finally catching the raiders.

A posed but interesting scene of the Orange & Alexandria's bridge crossing Bull's Run (Virginia), circa 1863, with Union soldiers in the foreground. The span was a Haupt Truss type designed by the United States Military Railroad's General Herman Haupt. American-Rails.com collection.

A posed but interesting scene of the Orange & Alexandria's bridge crossing Bull's Run (Virginia), circa 1863, with Union soldiers in the foreground. The span was a Haupt Truss type designed by the United States Military Railroad's General Herman Haupt. American-Rails.com collection.The twenty-two Union soldiers attempted to flee after abandoning the General but were soon discovered. For their bravery the U.S. troops were awarded the Congressional Medal Of Honor, some posthumously.

During the war's final years Southern railroads were in such horrid condition they offered virtually no strategic military importance.

In particular was the Louisville & Nashville which saw the most destruction of any system. The Confederacy's idea to win the war had largely been predicated on outlasting its aggressor.

A similar tactic was successful just over a century later when North Vietnam caused enough American casualties during the Vietnam War to cause the U.S. government to give up.

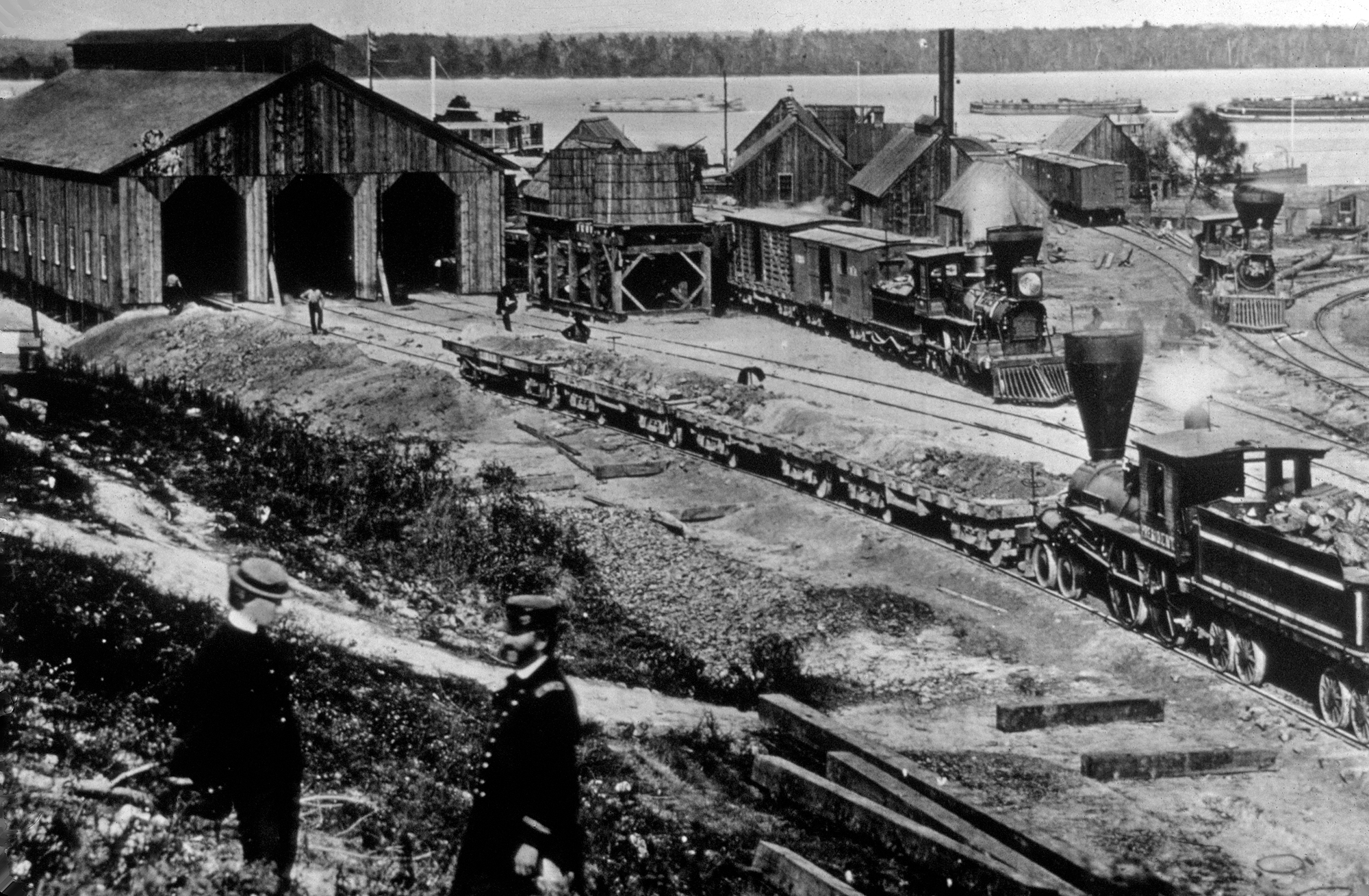

The United States Military Railroad's yard and engine house in City Point, Virginia, circa 1863. In the foreground is the 4-4-0 "President." American-Rails.com collection.

The United States Military Railroad's yard and engine house in City Point, Virginia, circa 1863. In the foreground is the 4-4-0 "President." American-Rails.com collection.The Confederacy faced a much more determined leader in President Lincoln who, for a number of reasons, did everything within his power to reunite the country and was eventually successful in that effort.

Looking back, the South may have achieved its desired result if Lincoln had never found an effective commander.

As Mr. Hankey points out, had the U.S. lost one battle here or there it may have turned the tide. Today, this is all conjecture, of course, but the questions and rhetoric regarding such are still brought up among historians.

At A Glance

Below is an interesting set of statistics concerning Union and Confederate railroad operations during the war.

North (220,000) South (26,000) | |

North (4,000) South (400) | |

1861 ($15) 1865 ($500) |

The United State Military Railroad (USMR) picks up debris following General Pope's retreat of the 2nd Battle of Bull Run at Clifton, Virginia in the fall of 1862. In the background two locomotives near Union Mills Station. American-Rails.com collection.

The United State Military Railroad (USMR) picks up debris following General Pope's retreat of the 2nd Battle of Bull Run at Clifton, Virginia in the fall of 1862. In the background two locomotives near Union Mills Station. American-Rails.com collection.Postscript

While the Civil War had emotionally and physically scarred the country, the railroad paved the way for further expansion and growth after hostilities ended.

Between 1850 and 1871 the federal government offered more than 170 million acres of western land to railroads in exchange for establishing new routes between the Midwest and the west coast.

Along with the aforementioned Transcontinental Railroad the Northern Pacific, financed by banker Jay Cooke, began a northerly route from Lake Superior at Duluth, Minnesota to Seattle, Washington in 1864.

Building through the very rugged and remote regions of western Montana, northern Idaho and Washington it took NP nearly twenty years before its completion in 1883 (hampered, partially, by the financial Panic of 1873).

Finally, two major technological advances were introduced just a few years after the war; George Westinghouse's automatic air brake of 1869 and Eli Janney's automatic coupler of 1873.

These two devices were so revolutionary they remain in regular use today as the most practical and efficient way to stop a train and join/detach equipment.

As the century came to a close railroads were rapidly opening new routes, branches, and corridors throughout the country.

Even though track widths were still prolific and a standard gauge had not yet been established the 1860's did witness improved cooperation, particularly in railroads' willingness to exchange freight.

Sources

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- "The Railroad War: How The Iron Road Changed The American Civil War," by John P. Hankey (March, 2011 issue of Trains Magazine)

- "The Great Locomotive Chase" by Rosemary Entringer (May, 1956 issue of Trains Magazine)

- Prince, Richard E. Central Of Georgia Railway And Connecting Lines. Salt Lake City: Stanway - Wheelwright Printing Company, 1976.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Recent Articles

-

Michigan Pumpkin Trains (2025): A Complete Guide

Mar 25, 25 12:38 PM

Discover where you can find pumpkin themed train rides in Michigan with this guide! -

C&O's 4-6-4 "Hudson" Locomotives (Class L): Specs, Roster, History

Mar 25, 25 12:36 AM

Chesapeake & Ohio's 4-6-4s included a small batch of Hudsons it put into service during the 1940s. One streamlined example, #490, survives today. -

C&O's M-1 Steam Turbine Locomotives: Specs, Roster, History

Mar 25, 25 12:27 AM

The Class M-1 steam turbines was a new technology the Chesapeake & Ohio envisioned to power its new "Chessie" streamliner. The locomotive proved unsuccessful.