"Quad Cities Rocket" (Train): Schedule, Route, Consist

Last revised: March 3, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Quad Cities Rocket was a late-era service operated by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific, charting its course between Chicago and Rock Island, Illinois.

This train was a legacy from one of Rock Island's flagship services, the Rocky Mountain Rocket. Following the curtailment of the Rocky Mountain Rocket's route to Omaha in 1966 and a brief period without a designated name, it emerged as The Cornhusker.

In 1970, the train saw its final transformation, with its western terminus scaled back to Rock Island. Train enthusiats colloquially referred to this service as the Quad Cities Rocket.

The train persisted as one of the two remaining services for the Rock Island Railroad after the advent of Amtrak on May 1, 1971—the Peoria Rocket being the other. In that same year, the route expanded to include a stop at Sheffield.

After battling with the state of Illinois to discontinue the train, the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled in May, 1978 the Rock Island could discontinue the service and the train made its final run on December 31, 1978.

A very tired Rock Island E8A, #650, has the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket" at Joliet, Illinois in March, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

A very tired Rock Island E8A, #650, has the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket" at Joliet, Illinois in March, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.Historical Context and Inception

In the Golden Age of rail travel, the 1930s through the 1950s, American railroads competed fiercely to attract passengers with faster, more luxurious, and more reliable services.

The Quad Cities Rocket harkens back to the Rock Island's original Rocket streamliner fleet which entered service in 1937.

The Rock Island, officially known as the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad, had a storied history dating back to the mid-19th century and was known for its innovative services and supportive infrastructure in the Midwest.

Design and Features

Heralding an era of streamlined Art Deco design, the original Rockets featured luxurious coaches, dining cars, and observation lounges, exuding an air of sophistication.

The train's streamlined locomotive, often early EMD models, epitomized the cutting-edge technology of the time, favoring both speed and efficiency.

The train's interior aesthetics married functionality with comfort. Plush seating, well-appointed dining services, and panoramic windows enriched the travel experience, allowing passengers to witness the evolving landscapes of the Midwest in style.

The Rocket's coaches were equipped with air conditioning— a hallmark of luxury at the time— making journeys comfortable even during the sweltering summer months.

Schedule and Operations

Serving a distance of approximately 180 miles between Chicago and the Quad Cities, the Quad Cities Rocket was designed for speed and frequency.

From its inception, the train made daily trips, with schedules crafted to accommodate both business and leisure travelers.

Two daily round trips were typically scheduled, ensuring that passengers could make timely returns the same day if needed.

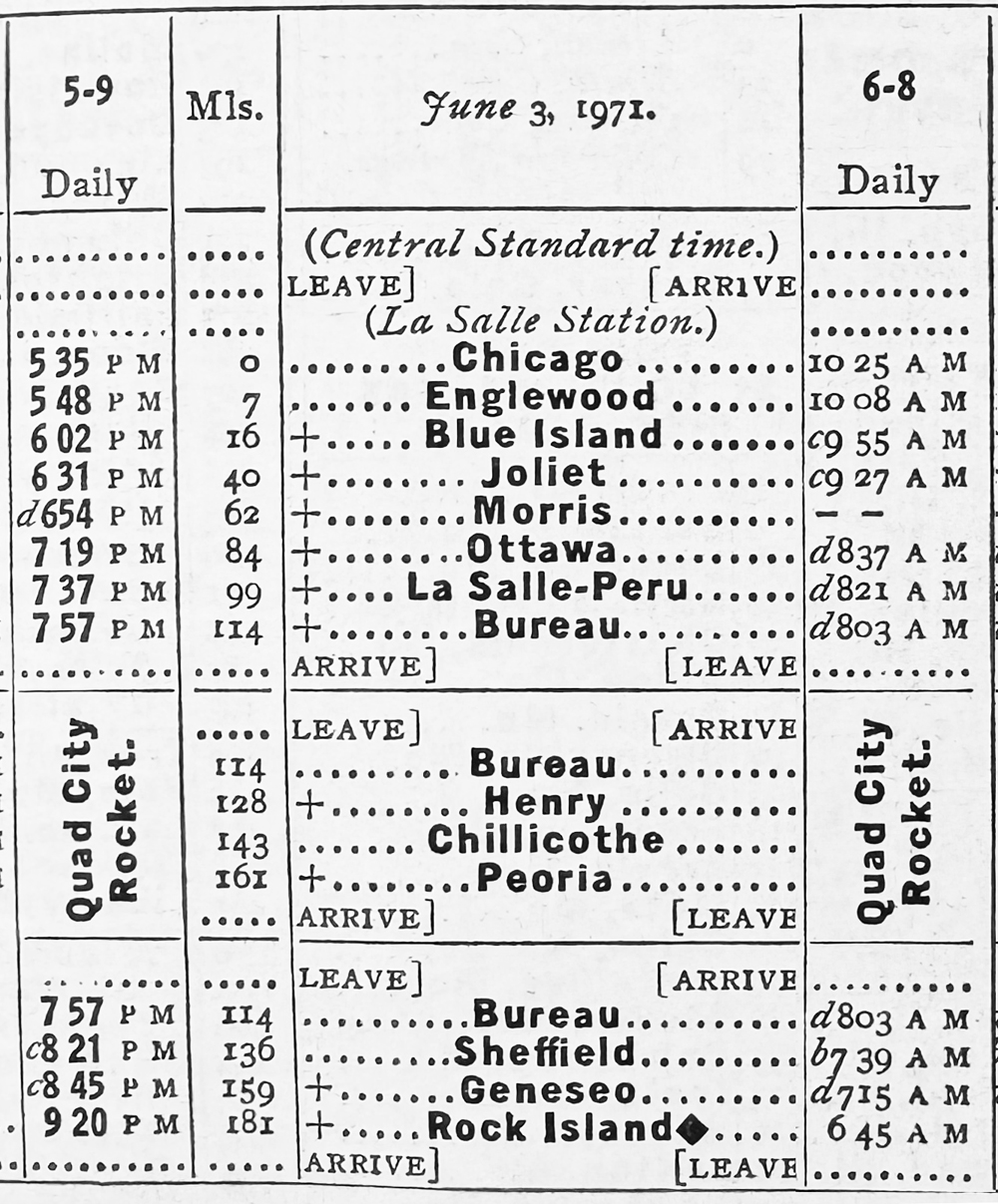

The typical schedule saw departures from Chicago's LaSalle Street Station, a hub bustling with activity, emphasizing the connection between one of the nation's largest cities and the economically vibrant Quad Cities region.

With stops at Joliet, Morris, Ottawa, LaSalle, and Bureau, among others, the Rocket seamlessly connected urban centers and smaller towns, fostering economic and social interplay.

Economic and Social Impact

The Rocket's influence stretched beyond mere transportation. It became a vital economic artery, facilitating commerce and trade. Businesses in the Quad Cities region found easier access to Chicago's vast market, while Chicagoans could travel conveniently for business or pleasure to the region. The Rocket also played a significant role during World War II, moving troops and equipment efficiently between key locations.

Passenger trains like the Quad Cities Rocket were more than transportation modes; they were social spaces where different strata of society mingled. They fostered camaraderie among frequent travelers and became integral in the lives of those who relied on the rail network for daily commutes or business travels.

Timetable (1971)

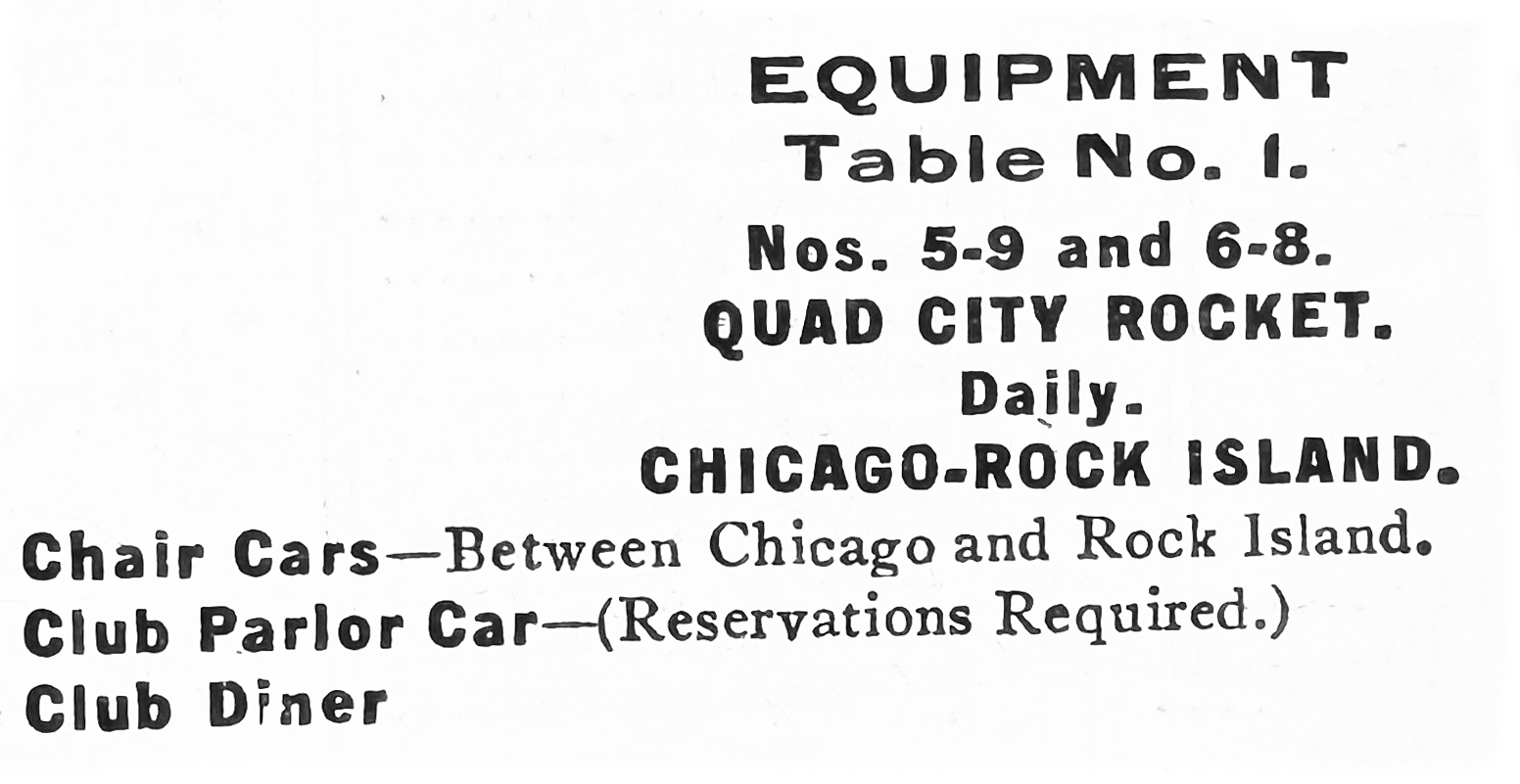

Consist (1971)

Challenges and Evolution

### Decline of the Quad Cities Rocket

By the 1960s and 1970s, the Rock Island Railroad was in financial decline, grappling with reduced passenger numbers and increasing operational costs. Despite the Railroad Reorganization Act of 1973, which aimed to restructure struggling railroads, the Rock Island line continued to falter.

The advent of the Amtrak system in 1971 also signaled the end of many historic passenger trains as Amtrak consolidated services under a federal mandate.

On April 1, 1971, the Rock Island made the decisive choice to opt-out of joining Amtrak, becoming the first railroad to do so. Financial constraints played a key role in this decision, as the railroad could not afford the Amtrak entry fee.

Under the prevailing legislation, railroads not participating in Amtrak were obliged to continue operating their passenger services for two more years.

By this time, the Rock Island was down to just two intercity services: the Chicago-Peoria and Chicago-Rock Island routes. According to the legal formula, joining Amtrak would have cost Rock Island $4.5 million.

Reflecting on this, Rock Island CEO Ted Desch remarked, "While the annual loss experienced by the two pairs of trains is great, the cost to Rock Island of joining Railpax, payable over the next three years, is very high."

Rail enthusiasts dubbed the remaining services the Peoria Rocket and Quad Cities Rocket. However, these trains were far from their rocket namesakes, suffering from slow orders that extended the 150-mile journey to over five hours.

In contrast, the same trip took just two-and-a-half hours in the 1960s. This decline marked the end of an era for the Rock Island's passenger services.

Ultimately, the decision to continue the trains proved financially draining. To help offset these losses, the State of Illinois provided a $1 million subsidy. Despite these efforts, the passenger numbers continued to dwindle, exacerbated by deteriorating track conditions.

Continuing to run the trains also siphoned significant revenue from the company, leading to annual losses exceeding $1 million.

After the Illinois Commerce Commission continually denied the railroad's attempts to cancel its remaining trains the CRI&P petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to intervene.

Following a protraced legal battle lasting more than two years the ICC granted the railroad's request in May, 1978 and the final trains ran on December 31, 1978. Alas, by this point it was too little, too late for the fabled Rock Island as the company was liquidated just two years later in 1980.

Legacy and Remembrance

Though the Quad Cities Rocket no longer runs, its legacy endures in many facets of rail history and regional lore. The train remains a subject of affection for rail enthusiasts and historians, who remember it as a symbol of Rock Island's ingenuity and dedication to excellent passenger service.

Remnants of the train's legacy can still be seen. Old rail depots, tracks, and memorabilia serve as a testament to an era when railroads were the lifeblood of the nation's transportation network. These relics are preserved in museums, historical societies, and even in the infrastructure that's now adapted for other uses.

The Quad Cities region and Chicago maintain strong ties, nurtured and developed significantly by the presence of services like the Quad Cities Rocket. Modern efforts to reinstate passenger rail service between Chicago and the Quad Cities reflect a continued appreciation of rail's potential to connect and enrich regions economically and socially.

Rock Island E8A #652 at Joliet, Illinois with the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket," circa 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

Rock Island E8A #652 at Joliet, Illinois with the eastbound "Quad Cities Rocket," circa 1974. American-Rails.com collection.Conclusion

The history of the Quad Cities Rocket is a tale of ambition, connection, challenge, and change. From its inception in 1971 to its final journey in 1978, this particular Rocket embodied the Rock Island's fighting spirit even if it was not, exactly, a first-class operation.

Its enduring legacy is a tribute to the pivotal role that regional rail services played in shaping economic landscapes and social interactions in the Midwest, bridging distances with steel tracks and human endeavor.

Recent Articles

-

Construction Continues On Railroad Museum Of Pennsylvania Roundhouse

Mar 05, 26 01:52 PM

Construction is underway on a long-anticipated roundhouse exhibit building at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, a project designed to preserve several of the most historically signific… -

Wisconsin Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:53 AM

Wisconsin might not be the first state that comes to mind when one thinks of wine, but this scenic region is increasingly gaining recognition for its unique offerings in viticulture. -

Alabama Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:50 AM

While the state might not be the first to come to mind when one thinks of wine or train travel, the unique concept of wine tasting trains adds a refreshing twist to the Alabama tourism scene. -

California's Dinner Train Rides In Sacramento

Mar 05, 26 09:49 AM

Just minutes from downtown Sacramento, the River Fox Train has carved out a niche that’s equal parts scenic railroad, social outing, and “pick-your-own-adventure” evening on the rails. -

New Jersey's Dinner Train Rides In Woodstown

Mar 05, 26 09:48 AM

For visitors who love experiences (not just attractions), Woodstown Central’s dinner-and-dining style trains have become a signature offering—especially for couples’ nights out, small friend groups, a… -

Tennessee Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:46 AM

Amidst the rolling hills and scenic landscapes of Tennessee, an exhilarating and interactive experience awaits those with a taste for mystery and intrigue. -

California Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 05, 26 09:16 AM

When it comes to experiencing the allure of crime-solving sprinkled with delicious dining, California's murder mystery dinner train rides have carved a niche for themselves among both locals and touri… -

UP 4014 To Visit WPRM For Fundraising Dinner

Mar 04, 26 11:32 PM

Rail enthusiasts in Northern California will have a rare opportunity this spring as Union Pacific 4014 — the world’s largest operating steam locomotive — is scheduled to visit the Western Pacific Rail… -

CPKC Sets New February Grain Shipping Record

Mar 04, 26 10:57 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) announced on March 3 that it established a new company record for grain transportation during the month of February. -

Hunterdon Wine Express Train Announces 2026 Season Dates

Mar 04, 26 01:57 PM

The Hunterdon Wine Express returns for its 2026 season from April through September, offering a four-hour wine country experience that combines historic rail travel, guided wine tasting, lunch, and ti… -

Washington's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 11:43 AM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Illinois "Murder Mystery" Dinner Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 11:39 AM

Among Illinois's scenic train rides, one of the most unique and captivating experiences is the murder mystery excursion. -

OmniTRAX Unveils Restored Business Car "Savannah Sunrise"

Mar 04, 26 11:18 AM

Short line and industrial railroad operator OmniTRAX has completed the restoration of a vintage business car “Savannah Sunrise," built in 1959 by National Steel Car. -

CN Unveils Two America250 Locomotives

Mar 04, 26 10:42 AM

Canadian National (CN) announced today the launch of its America250 celebration, unveiling two specially painted locomotives that will operate across the railroad’s U.S. network in tribute to the upco… -

Vermont Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 10:29 AM

There are currently murder mystery dinner trains offered in Vermont but until recently the Champlain Valley Dinner Train offered such a trip! -

Washington Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 10:25 AM

Here’s a detailed look at where and how to ride, what to expect, and practical tips to make the most of wine tasting by rail in Washington. -

Kentucky Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 04, 26 10:21 AM

Kentucky, often celebrated for its rolling pastures, thoroughbred horses, and bourbon legacy, has been cultivating another gem in its storied landscapes; enjoying wine by rail. -

CPKC Unveils KCS 1776 Honoring America’s 250th

Mar 03, 26 04:32 PM

Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) today officially unveiled a striking new commemorative locomotive, KCS 1776, a specially painted Tier 4 ET44AC designed to celebrate the upcoming 250th anniversary… -

Illinois Railway Museum Completes Barn 15

Mar 03, 26 11:54 AM

The Illinois Railway Museum announced on March 3, 2026 it had completed Barn 15, adding 2000 feet of indoor storage space. -

North Carolina's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 10:14 AM

If you’re looking for the most “Bryson City” way to combine railroading and local flavor, the Smoky Mountain Beer Run is the one to circle on the calendar. -

Connecticut's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:59 AM

While the Naugatuck Railroad runs a variety of trips throughout the year, one event has quickly become a “circle it on the calendar” outing for fans of great food and spirited tastings: the BBQ & Bour… -

New Mexico's Murder Mystery Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:55 AM

Among Sky Railway's most theatrical offerings is “A Murder Mystery,” a 2–2.5 hour immersive production that drops passengers into a stylized whodunit on the rails. -

Michigan Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:50 AM

Among the lesser-known treasures of this state are the intriguing murder mystery dinner train rides—a perfect blend of suspense, dining, and scenic exploration. -

Florida Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:45 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards. -

Texas Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 03, 26 09:43 AM

This article invites you on a metaphorical journey through some of these unique wine tasting train experiences in Texas. -

Nevada Museum Acquires Amtrak F40PHR 315

Mar 02, 26 10:32 PM

The Nevada State Railroad Museum has stated they have acquired Amtrak F40PHR 315 from Western Rail, Inc. where it will be used for static display. -

Virginia Railway Express Surpasses 100 Million Riders

Mar 02, 26 09:42 PM

In October 2025, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) reached one of the most significant milestones in its history, officially carrying its 100 millionth passenger since beginning operations more than… -

Restoration Continues On New Haven RS3 529

Mar 02, 26 11:29 AM

The Railroad Museum of New England's efforts to completely restore New Haven RS3 529 to operating condition as they provide the latest updates on the project. -

American Freedom Train No. 250 Completes FRA Steam Test

Mar 02, 26 10:17 AM

One of the most anticipated steam locomotive restorations in modern preservation reached a major milestone this week as American Freedom Train 4-8-4 No. 250 successfully completed a federally observed… -

Indiana's Beer Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 10:00 AM

On select dates, the French Lick Scenic Railway adds a social twist with its popular Beer Tasting Train—a 21+ evening built around craft pours, rail ambience, and views you can’t get from the highway. -

Maryland's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:54 AM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

California's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:46 AM

There is currently just one location in California offering whiskey tasting by train, the famous Skunk Train in Fort Bragg. -

Virginia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:42 AM

Among the state's railroad attractions, murder mystery dinner trains stand out as a captivating fusion of theatrical entertainment, fine dining, and scenic travel. -

New York Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:32 AM

This article will delve into the history, offerings, and appeal of wine tasting trains in New York, guiding you through a unique experience that combines the romance of the rails with the sophisticati… -

Michigan Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 02, 26 09:30 AM

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of Michigan’s wine tasting train experiences that cater to both wine connoisseurs and railway aficionados. -

NS Completes 1,000th DC-to-AC Locomotive Conversion

Mar 01, 26 11:26 PM

In October 2025, Norfolk Southern Railway reached one of the most significant mechanical milestones in modern North American railroading, announcing completion of its 1,000th DC-to-AC locomotive conve… -

California Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:11 AM

California is home to many tourist railroads and museums; several offer Easter-themed train rides for the entire family. -

North Carolina Easter Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:09 AM

The springs are typically warm and balmy in the Tarheel State and a few tourist trains here offer Easter-themed train rides. -

Maryland Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:05 AM

Maryland is known for its scenic landscapes, historical landmarks, and vibrant culture, but did you know that it’s also home to some of the most thrilling murder mystery dinner trains? -

Minnesota Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:03 AM

Murder mystery dinner trains offer an enticing blend of suspense, culinary delight, and perpetual motion, where passengers become both detectives and dining companions on an unforgettable journey. -

Indiana Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 10:01 AM

In this article, we'll delve into the experience of wine tasting trains in Indiana, exploring their routes, services, and the rising popularity of this unique adventure. -

South Dakota Wine Tasting Train Rides

Mar 01, 26 09:58 AM

For wine enthusiasts and adventurers alike, South Dakota introduces a novel way to experience its local viticulture: wine tasting aboard the Black Hills Central Railroad. -

Metro-North Unveils Veterans Heritage Locomotive

Feb 28, 26 11:02 PM

The Metro-North Railroad marked Veterans Day 2025 with the unveiling of a striking new heritage locomotive honoring the service and sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Pennsylvania's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:46 AM

For whiskey aficionados and history buffs alike, a train ride through the Keystone State offering such spirits provides a unique and memorable experience. -

Alabama's Whiskey Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:44 AM

With a little planning, you can build a memorable whiskey-and-rails getaway in the Heart of Dixie. -

Georgia Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:43 AM

In the heart of the Peach State, a unique form of entertainment combines the thrill of a murder mystery with the charm of a historic train ride. -

Colorado Murder Mystery Dinner Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:40 AM

Nestled among the breathtaking vistas and rugged terrains of Colorado lies a unique fusion of theater, gastronomy, and travel—a murder mystery dinner train ride. -

New Mexico Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:37 AM

For oenophiles and adventure seekers alike, wine tasting train rides in New Mexico provide a unique opportunity to explore the region's vineyards in comfort and style. -

Ohio Wine Tasting Train Rides

Feb 28, 26 08:35 AM

Among the intriguing ways to experience Ohio's splendor is aboard the wine tasting trains that journey through some of Ohio's most picturesque vineyards and wineries. -

KC Streetcar Ridership Surges With Opening of Main Street Extension

Feb 27, 26 11:24 AM

Kansas City’s investment in modern urban rail transit is already paying dividends, especially following the opening of the Main Street Extension.