Pennsylvania Station (NYC): "One Entered The City Like A God..."

Last revised: September 15, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Rise And Fall Of Penn Station was a Public Broadcasting documentary, which first aired on February 28, 2014. It was only an hour long but eloquently summarized the tragic loss of an architectural masterpiece and National Historic Landmark.

Argued as the greatest railroad terminal ever built Pennsylvania Station, designed in the Beaux-Arts style, provided the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad its first access into New York City's coveted downtown area, Manhattan Island.

Today, it's hard to fathom such a grand and expensive facility could survive within a lifetime before its demise.

Alas, in a desperate attempt by a fading icon to save its future the magnificent structure was razed.

Adding insult to this negligent act, the terminal's above-ground portion was promptly replaced with what New Yorkers still consider an incredible eyesore, Madison Square Garden.

Today, the ghost of Penn Station survives as a functioning terminal witnessing millions of travelers annually. However, this underground facility carries no magic or allure, hated nearly as much as the Garden which sits atop it.

A bird's eye view of Pennsylvania Station, seen here circa 1910. Note the lack of high-rise buildings in downtown Manhattan. That would soon change. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

A bird's eye view of Pennsylvania Station, seen here circa 1910. Note the lack of high-rise buildings in downtown Manhattan. That would soon change. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.History

Perhaps architect Vincent Scully articulated it best when he famously stated after the legendary building was razed:

"One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat."

Pennsylvania Station was the dream of its then-president, Alexander Cassatt. While the PRR grew into one of the most powerful corporations in the world it wasn't born in New York City.

Such a coveted existence belonged only to the New York Central whose predecessors provided two direct northbound routes out of Manhatttan.

Into the early 20th century the NYC enjoyed this exclusive access and happily exploited it via Grand Central Depot/Grand Central Station, and later Grand Central Terminal. Only after a monumental undertaking requiring millions did the PRR finally break up this monopoly.

Birth Of The Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad had humble beginnings, chartered by the Pennsylvania state legislature on April 13, 1846 to provide direct rail access between the capital at Harrisburg and Pittsburgh.

The PRR was formed long after its two principal rivals, nearly 20 years following the birth of the Baltimore & Ohio and NYC's earliest predecessors.

As railroads expanded and it became clear the future of transportation lay in the railroad business interests in the Pennsylvania's largest cities were growing concerned.

At the time the state had no notable railroad of its own and by 1843 the B&O (a creation of Baltimore) was well underway, pushing for access into Pittsburgh.

Despite its late start the PRR quickly expanded and, according to Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon's book, "Pennsylvania Railroad," opened for service between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh on December 10, 1852.

The main concourse of Pennsylvania Station just before it opened in 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

The main concourse of Pennsylvania Station just before it opened in 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.Throughout the latter 1800s the PRR continued its rapid growth.

Thanks to its acquisitions of several other systems the PRR reached Chicago by January 1, 1859 (via the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago) and through various additional subsidiaries had direct access into St. Louis by 1870 (connecting Columbus, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis along the way).

This western expansion, led by PRR president J. Edgar Thomson, established the railroad as a formidable and powerful eastern giant.

As these expansions took place the company also looked to the east, beyond Harrisburg and Philadelphia.

Once again the PRR largely relied on acquisitions for to reach these new markets; the Cumberland Valley (1859) opened a link to Hagerstown while the Northern Central provided entry into Baltimore.

A bit more work was required, however, for access to the Hudson River waterfront across from Manhattan.

The huge Corinthian columns loomed inside the terminal, as seen here on May 10, 1962 soon before the structure was demolished. Cervin Robinson photo.

The huge Corinthian columns loomed inside the terminal, as seen here on May 10, 1962 soon before the structure was demolished. Cervin Robinson photo.By the 1850s it was clear New York would become the dominant eastern port and railroads were fighting for access to the city.

After the dust settled several notable companies would eventually reach there with names like:

- Lehigh Valley (LV)

- Baltimore & Ohio

- Erie

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western (DL&W)

- New York, New Haven & Hartford (NYNH&H)

- New York Central

- Pennsylvania

- Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ)

However, only four provided trunk line status to Chicago and just two would serve Manhattan directly.

At first the PRR attempted to offer through service east of Philadelphia in conjunction with the Philadelphia & Reading (Reading) and CNJ to compete against the growing consortium which eventually became the New York Central.

However, this prospect proved difficult, requiring two interchanges and no rail link into Manhattan.

President Thompson, who always preferred direct access, realized the only way to remedy this situation was own the tracks himself.

The PRR pushed beyond Philadelphia during the Civil War by acquiring the Philadelphia & Trenton and United Canal & Railroad Companies.

The UC&RC comprised several smaller systems (Camden & Amboy, New Jersey Railroad, Belvidere-Delaware Rail Road, West Jersey Railroad, Cape May & Millville, and Delaware & Raritan Canal Company) which offered through service as far as Jersey City, New Jersey.

Along the waterfront the PRR opened the massive Exchange Place Terminal with ferry service provided across the Hudson into downtown Manhattan.

It was one of several facilities that sprang up along the waterfront between Edgewater and Jersey City.

Construction

Pennsylvania Station's façade at 7th Avenue and West 31st Street is seen here on May 8, 1962. Cervin Robinson photo

Pennsylvania Station's façade at 7th Avenue and West 31st Street is seen here on May 8, 1962. Cervin Robinson photoOver time the PRR continued to expand across the east opening rail service across much of its home state. It would also reach Buffalo, had access into northern Michigan, and expanded throughout the Delmarva Peninsula.

At its peak the system covered more than 10,000 route miles. Alas, direct entry into New York continued to haunt the self-proclaimed "Standard Railroad Of The World," which battled only the equally powerful New York Central for dominance in the East.

It would be Alexander Cassatt who changed all of this leaving a legacy that was Pennsylvania Station. Cassatt had joined the PRR in 1861 as an engineer and worked his way up through the company.

He reached the level of vice-president but was passed over for the presidency in 1880 by George Brooke Roberts.

This incident frustrated Cassatt and he left the company in 1882. He was later recalled in 1899 for the position and wasted no time fixing what he saw as the PRR's glaring weakness.

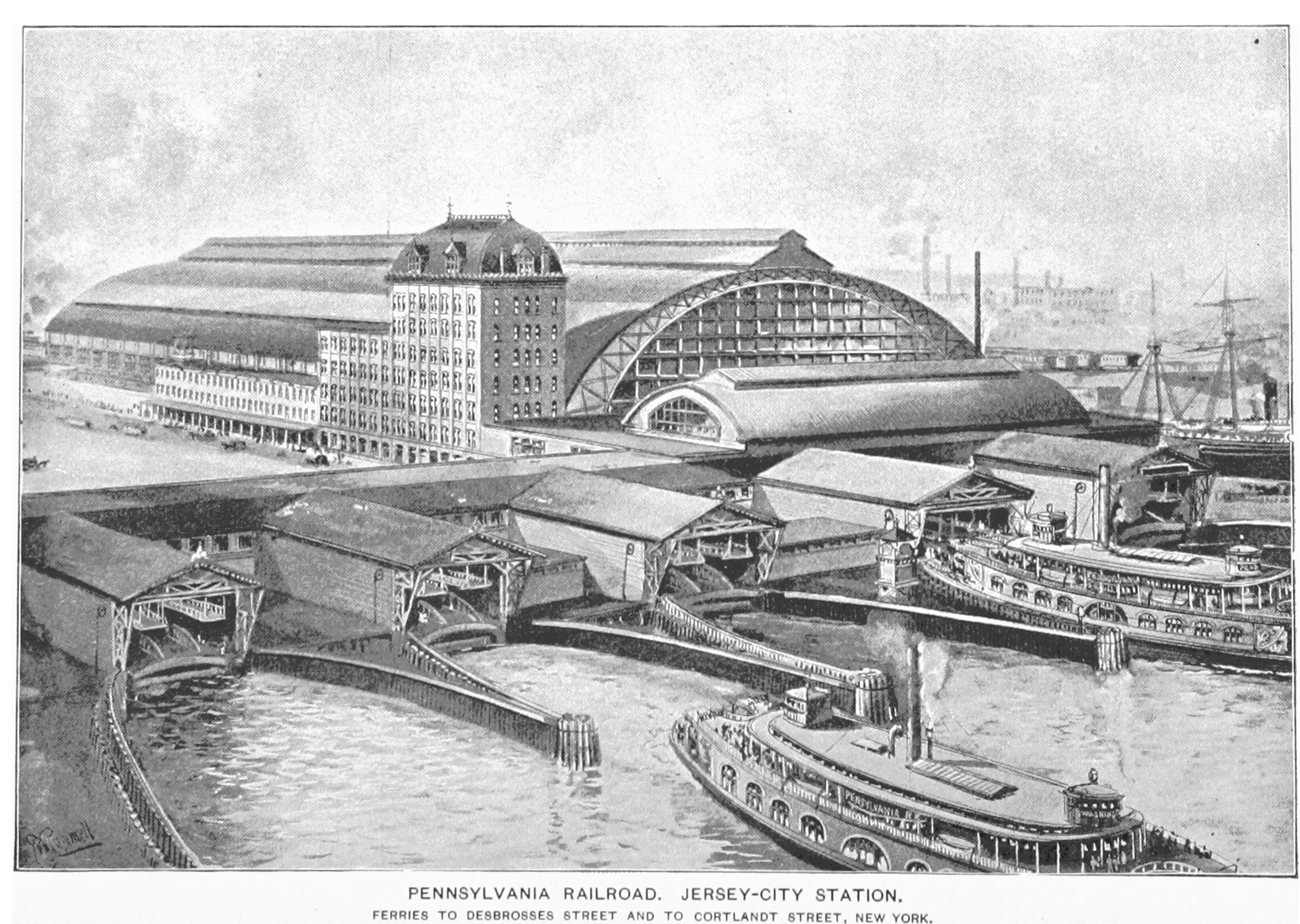

Exchange Place Terminal

The New Jersey waterfront became a busy, crowded place directly across the Hudson River from downtown Manhattan during the heyday of rail service at the turn of the 20th century.

During this time it was home to five major passenger terminals. From north to south these included the West Shore Railroad's (New York Central) Weekhawken Terminal, Erie Railroad's Pavonia Terminal, Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal, Pennsylvania's Exchange Place Terminal, and Jersey Central's massive Jersey City/Communipaw Terminal.

From an area known as Paulus Hook (Jersey City) the first ferry service was launched to Manhattan in 1812.

This event was followed by the New Jersey Rail Road & Transportation Company's launching rail service from Jersey City to Newark on September 15, 1834.

In 1867 the NJRR became part of the much larger United New Jersey Railroad & Canal Companies (which included the previously mentioned Camden & Amboy), subsequently leased by the PRR in 1871.

The UNJ corridor became PRR's primary route between Philadelphia and New York although it terminated at originally Jersey City.

The railroad's first, true waterfront passenger terminal was opened in 1876, which replaced an earlier structure acquired in 1871.

There were additional improvements between 1888 and 1892, which allowed passengers to move from their train to the ferry slips without ever being exposed to the outdoors.

As Mr. Solomon notes in his book, "Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals," its most impressive feature was a massive glass and steel arched train shed completed in 1891, said to be the largest in the world then.

Following the opening of Pennsylvania Station in 1910 Exchange Place remained as a commuter hub, including its ferry slips.

As suburban operations wound down and the PRR became more financially unstable it shuttered the station in 1961 with the last train pulling out on November 17th.

Today, Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) continues to operate a facility called Exchange Place Station at the site although the ferry slips have long since been demolished.

The culmination of New York Central's link into Manhattan was Grand Central Depot (later renamed Grand Central Station and eventually replaced by the magnificent Grand Central Terminal).

It was located along 42nd Street and combined Vanderbilt's original New York Central, Hudson River, and New York & Harlem properties within a centralized terminal.

Cassatt despised this and began making plans for a facility which would not only dwarf Grand Central but also rival the greatest terminals ever built, anywhere.

The only way to actually reach Manhattan, of course, was by finding a way across the formidable Hudson River. An idea was put forth to construct a long suspension bridge but estimated at an astronomical $100 million this proved untenable.

Tunneling came to mind but the Hudson was nearly a mile-wide and smoke from steam locomotives would cause asphyxiation.

In addition, smoke-clogged bores would impair the train crew's vision likely resulting in an accident similar to the one NYC&HR experienced within the Park Avenue Tunnel on January 8, 1902.

A southward view of the concourse and its famous clock as seen on April 24, 1962. Cervin Robinson photo.

A southward view of the concourse and its famous clock as seen on April 24, 1962. Cervin Robinson photo.This incident had also banned steam locomotives throughout the city. After visiting his sister in France and seeing the newly completed Gare d'Orsay in Paris, Cassatt discovered how the PRR would reach Manhattan, electrification.

The facility operated the world's first electrified railroad, which reached the terminal via tunnels running near the Seine River.

At the turn of the 20th century, electric locomotives were still a novelty but gaining in popularity.

Aside from Paris both the B&O and NYC&HR had launched their owned electrification projects; the former in its Howard Street Tunnel (Baltimore) and the latter in Manhattan following the Park Avenue accident.

To build Pennsylvania Station, Cassatt hired New York's esteemed architectural firm McKim, Mead & White headed by Charles McKim, William Rutherford Mead, and Stanford White.

According to Solomon's, "Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals," Cassatt liked McKim's idea, designing a terminal based from Rome's Baths of Caracalla and Basilica of Constantine.

Both men worked together closely on the project and held similar tastes in architecture. For Cassatt, Pennsylvania Station went beyond projecting a symbol of his company's dominance.

It was also meant to fulfill a very real transportation need linking the island with its suburbs. As "The Rise and Fall of Penn Station" notes, acquiring the needed property within Manhattan was a low key affair in order to keep purchasing prices low.

It began in the fall of 1901 when men walked from door to door with large sums of cash asking individuals to sell their buildings or places of business.

The location was the so-called "Tenderloin," a named given to an entertainment and red-light district in the downtown area.

They eventually got what they needed, the four blocks from West 31st Street to West 33rd Street between 7th and 9th Avenues. In all, the land totaled 7.5 acres, an incredible amount of real estate at that time for a single project.

Construction began in June of 1906 and was completed by 1910. The station’s enormous main concourse was modeled after London’s famous Crystal Palace.

With its ceiling of glass and ironwork the interior was bathed in sunlight. In addition, the main waiting room replicated the Roman Baths complete with the same Travertine marble from Italy imported for the project.

Grand Corinthian columns rose 60 feet above the room to sustain a vaulted ceiling that reached 150 feet!

The building's magnificence did not stop there. Outside, huge Doric columns of pink Milford granite (quarried in Massachusetts) supported the Seventh Avenue façade and other terminal entrances.

Perched above each entry way were six giant eagles. The work of sculptor Adolph A. Weinman these guardians stayed true to the terminal's Roman theme.

Unfortunately, neither McKim nor Cassatt would live to see their vision finished as both passed away before its completion (Cassatt died on December 28, 1906 and McKim on September 14, 1908).

The big dig is underway as excavation work continues on Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan circa 1908. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

The big dig is underway as excavation work continues on Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan circa 1908. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.The Great Tunnels

While the history of Pennsylvania Station often focuses on the above ground station what truly made it a superb transportation hub was the underground tunnels, the first of their kind in the United States.

The project, which began in 1902, was spearheaded by company engineer Samuel Rea (who later became PRR's president) with assistance from Charles Jacobs, an expert in tunnel construction and engineering.

The entire project would encompass 16 miles of underground rail lines connecting the Hudson's west side with downtown Manhattan (two tunnels with a large 21-track staging yard beneath the station) and continuing on under the East River where four tunnels would connect with PRR's subsidiary, the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR).

From Long Island an extension would see tracks head north, pass over the East River (via the Hell Gate Bridge), and offer a connection with the New Haven Railroad for through service into New England (this segment would not open until the 1916 completion of Hell Gate). O

n September 11, 1906 the Hudson River Tunnels (also known as the North River Tunnels) were completed a full year ahead of schedule although those bored beneath the East River were much more difficult and required a few more years of work (1909).

Inside Pennsylvania Station at track level just before the facility opened in 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

Inside Pennsylvania Station at track level just before the facility opened in 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.Operation

While the LIRR had launched rail service to Pennsylvania Station on September 8th the terminal officially opened for all rail traffic on November 27, 1910.

The facility was a marvel that awestruck the public. The New York Times described it as "...the largest and handsomest in the world."

The station had required four years to complete comprising 27,000 tons of steel, 500,000 cubic feet of granite, 83,000 square feet of sky lights, and 17 million bricks.

The terminal and its accompanying tunnels had cost more than $114 million (nearly $3 billion today).

While Cassatt never had the chance to see his legacy finished he accomplished his goal of providing a gift to the people of New York and monument to the PRR.

Following its opening Pennsylvania Station witnessed 18 million travelers annually, a number that jumped to over 100 million by World War II, the busiest time in its history.

During its peak years there were about 1,000 rail moves daily handling 144 trains per hour, all protected by an early block signaling system using colored lights.

Many of the travelers using the facility were local suburbanites and commuters pouring in from Long Island, New England (via the NYNH&H), and parts of New Jersey.

In addition, now that it equaled New York Central for direct Manhattan service the PRR fielded an impressive fleet of long-distance trains (many came of age after the streamliner was introduced in the 1930s) with names like:

- Broadway Limited

- Pittsburgher

- Spirit of St. Louis,

- Penn Texas

- General

- Red Arrow

- Trail Blazer

These trains, and others, reached far and wide across the PRR system to cities such as Chicago, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, Detroit, St. Louis, Louisville, Buffalo, and Indianapolis.

Downfall & Demolition

In the postwar years Pennsylvania Station began a slow decline as the traveling public abandoned trains for highways and airliners.

To make matters worse the PRR found itself in a spiraling situation as freight traffic also declined due to the increasing loss of heavy industry.

After the war these businesses shutdown throughout the Midwest and Northeast, which had comprised a large percentage of its business.

A 1957 nationwide recession hit the railroad hard and management realized if some drastic action was not taken the PRR may have to do the unthinkable, file for bankruptcy.

In late 1957 the railroad began initial discussions with its longtime rival, the New York Central, regarding a possible merger.

By the dawn of the 1960s it was nearing desperation and during this critical time made the stunning decision to raze Pennsylvania Station.

The plan was announced in 1961 as the PRR announced it would sell the lucrative air rights above the facility. The actual demolition would begin two years later in 1963.

Despite pleas and protests to save the historic building its demise began on the gloomy morning of October 28th. The facility was so well built that it took contractors three years to finish the job, a testament to its construction.

In its place was born today’s Madison Square Garden considered by many a visual and architectural nightmare. While the above-ground station was gone the actual below-ground terminal remained and continues to serve millions of commuters and Amtrak passengers annually.

The loss of Penn Station enraged and shocked the public. The New York Times scathed the city for allowing such an act of corporate vandalism against one of the city's greatest architectural masterpieces.

Its demise brought about swift political change as the city launched the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, created by Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. in April of 1965.

It was charged with administering the city's Landmarks Preservation Law and overseeing the protection of historic buildings. One of its first acts designated nearby Grand Central Terminal a city landmark, sparing it a similar fate.

Looking down from Pennsylvania Station's main concourse to track level circa 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

Looking down from Pennsylvania Station's main concourse to track level circa 1910. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.Today

In recent years attempts have been made to improve Pennsylvania Station. One idea was to redesign the Farley Post Office, originally constructed alongside but across the street from Pennsylvania Station.

It was similar to the original terminal with a plan to transform it into a magnificent waiting room but so far nothing has materialized beyond discussions.

In more recent times a proposal was brought forth suggesting the alternation of Two Penn Plaza, which sits beside Madison Square Garden and atop the underground terminal.

The design would essentially create a glass-filled entrance but largely be devoid of any architectural significance.

Today, Penn Station hosts 1,200 trains a day while 600,000 commuters and Amtrak passengers use it every weekday.

It is clear that something needs to be done as the criticism of the current arrangement remains as strong as ever, particularly since Penn Station sees far more use than Grand Central.

A view of Pennsylvania Station's concourse during its final days of service on April 24, 1962. Cervin Robinson photo.

A view of Pennsylvania Station's concourse during its final days of service on April 24, 1962. Cervin Robinson photo.As recently as early 2016 an article in Forbes by Justin Shubow, entitled "It's Time To Rebuild New York's Original Penn Station," argues for the restoration of the original terminal albeit slightly altered to meet today's technological and modern needs.

Perhaps most interesting is the idea has been deemed economically feasible using its original drawings and blueprints held at the New-York Historical Society's archive.

Led by Richard W. Cameron, principal designer at Atelier & Company, there are efforts underway to see Pennsylvania Station's resurrection.

While none of these ideas have gained in significant traction, largely due to the project's cost, hope remains that a semblance of this once mighty terminal will return to the New York skyline.

In the end, we can always hope the plans will call for something similar to what once was.

Whatever becomes of the site the original Pennsylvania Station will forever be remembered as an architectural wonder, unrivaled in beauty and design.

To see a collection of historic Pennsylvania Station photos housed at the Library of Congress please click here.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-37): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 12:57 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-37 Mikes were itsdge steamers to enter service in the late 1920s. Today, all but two survive. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-36): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 11:09 AM

The Rio Grande's K-36 2-8-2s were its last new Mikados purchased for narrow-gauge use. Today, all but one survives. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive.