The Pacific Extension (Milwaukee Road): Map, Abandonment, History

Last revised: November 6, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The then Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad had been in

operation since the late 1840's with a heritage dating back to the tiny

Milwaukee & Mississippi Railroad which served its namesake city.

By the 1880s the CM&StP had stretched to a more than 5,000-mile

system reaching several Midwestern states.

However, as the railroad's top management saw it, this was a problem. To effectively compete with rivals Northern Pacific and Great Northern Railways the CM&StP felt it needed its own line to the west coast instead of simply receiving meager interchange traffic, which garnered little money as long-haul freight was where the profits truly were.

History

The Milwaukee Road was not your typical Midwestern granger, or railroad in general. Even by the early 20th century most major Class I's were under the control of handful of men, names like Gould, Hill, and Harriman.

But not the Milwaukee; until its untimely end in 1985 the company was independent of these influential individuals, even staving off a potential buyout by James Hill.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-71 leads a westbound time freight east of Avery, Idaho in August, 1972. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-71 leads a westbound time freight east of Avery, Idaho in August, 1972. American-Rails.com collection.Construction

In 1901 the first surveying work began and it was estimated the more than 1,400-mile western extension would cost the railroad around $45 million adding more than 25% to its total system mileage. However, four years later this number was readjusted to $60 million.

What made the extension so terribly expensive was partly due to the right-of-way costs. Unlike the GN and NP the CM&StP was not given free government land grants and had to both purchase all of its land from private landowners as well as take over a number of small, new, or floundering railroads across the region.

Still, this did not hinder the effort and in 1905 the railroad's board approved the building of what would become known as the Pacific Coast, or Puget Sound Extension.

A year later in 1906 the actual construction on the western extension commenced with the railroad itself building west from its western-most terminus at the time, tiny MoBridge, South Dakota reaching more than 1,000 miles into western Montana.

Overview

Harlowton, Montana - Avery, Idaho: 438 miles (opened; November, 1916) Othello, Washington - Tacoma: 207 miles (opened; March, 1920) Black River Junction, Washington - Seattle Union Station: 9 miles (opened; July, 1927) | |

Three Forks - Deer Lodge, Montana (November 30, 1915) | |

Two Dot, Montana (#1) Loweth, Montana (#2) Francis, Montana (#3) Eustis, Montana (#4) Piedmont, Montana (#5) Janney, Montana (#6) Morel, Montana (#7) Gold Creek, Montana (#8) Ravenna, Montana (#9) Primrose, Montana (#10) Tarkio, Montana (#11) Drexel, Montana (#12) East Portal, Montana (#13) Avery, Idaho (#14) Taunton, Washington (#15) Doris, Washington (#16) Kittitas, Washington (#17) Cle Elum, Washington (#18) Hyak, Washington (#19) Cedar Falls, Washington (#20) Renton, Washington (#21) Tacoma Junction, Washington (#22) | |

#1 (Red Tunnel, Montana) #2 (Canyon Tunnel, Montana) #3 (Eagle Nest Tunnel, Montana) #4 (Josephine, Montana) #5 (Deer Park #1, Montana) #6 (Deer Park #2, Montana) #7 (Deer Park #3, Montana) #8 (Lombard, Montana) #9 (Fish Creek, Montana) #10 (Pipestone Pass, Montana) #11 (Blacktail #1, Montana) #12 (Blacktail #2, Montana) #13 (Garrison, Montana) #14 (Nimrod, Montana) #15 (Beavertail Tunnel, Montana) #16 (Bonner, Montana) #17 (Nine Mile Tunnel, Montana) #18 (Cyr, Montana) #19 (Dominion Creek, Montana) #20 (St. Paul Pass, Montana/Idaho) #21 (Dry Creek, Idaho) #22 (Moss Creek, Idaho) #23 (Small Creek Tunnel #1, Idaho) #24 (Small Creek Tunnel #2, Idaho) #25 (Loop Creek Tunnel #1, Idaho) #26 (Loop Creek Tunnel #2, Idaho) #27 (Clear Creek Tunnel #1, Idaho) #28 (Clear Creek Tunnel #2) #29 (Deer Creek Tunnel #1, Idaho) #30 (Deer Creek Tunnel #2, Idaho) #31 (Glade Creek Tunnel #1, Idaho) #32 (Glade Creek Tunnel #2, Idaho) #33 )Kyle, Idaho) #34 (Stetson Tunnel #1, Idaho) #35 (Stetson Tunnel #2, Idaho) #36 (Stetson Tunnel #3, Idaho) #37 (Herrick Tunnel, Idaho) #38 (Benewah Tunnel, Idaho) #39 (Watts/Sorrento Tunnel, Idaho) #40 (Rosalia Tunnel, Washington): Daylighted, 1911 #41 (Rock Lake Tunnel #1, Washington) #42 (Rock Lake Tunnel #2, Washington) #43 (Johnson Creek Tunnel, Washington) #44 (Horlick Tunnel #1, Washington) #45 (Horlick Tunnel #2, Washington) #46 (Easton Tunnel, Washington) #47 (Whittier Tunnel, Washington) #48 (Snoqualmie Tunnel, Washington) #49 (Landsburg Tunnel, Washington): Bypassed, 1945 #52 (Noble Tunnel, Washington): Daylighted, 1912 | |

Sources (Above Table):

- Murray, Tom. Milwaukee Road, The. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2005.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road Remembered. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota, 2008 (Second Edition).

- Sol, Michael (Milwaukee Road Archives)

- Wood, Charles R. and Wood, Dorothy M. Milwaukee Road West. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1972.

- Clark, Rodney A. Milwaukee Electrification, The: A Proud Era Passes. July-August, 1973.

From Seattle, heading east, the line was constructed by contractor Horace Chapin Henry, which completed the 450-mile stretch into western Montana.

Amazingly, in just three short years the entire extension had been completed and on May 19, 1909 a Golden Spike was driven at Garrison, Montana commemorating the opening of the new route. Not only was the line built in record time but it also was an engineering marvel.

While the Puget Sound Extension would ultimately cross no less than five different mountain ranges on its way to Seattle including the Belts, Bitterroots, Cascades, Rockies, and Saddles it did so at a much lower ruling grade than its competitors.

The line would also be at least 18 miles shorter than either the NP's or GN's, and traveled through fewer population centers cutting down transit times even further, as well as giving the CM&StP a more direct route.

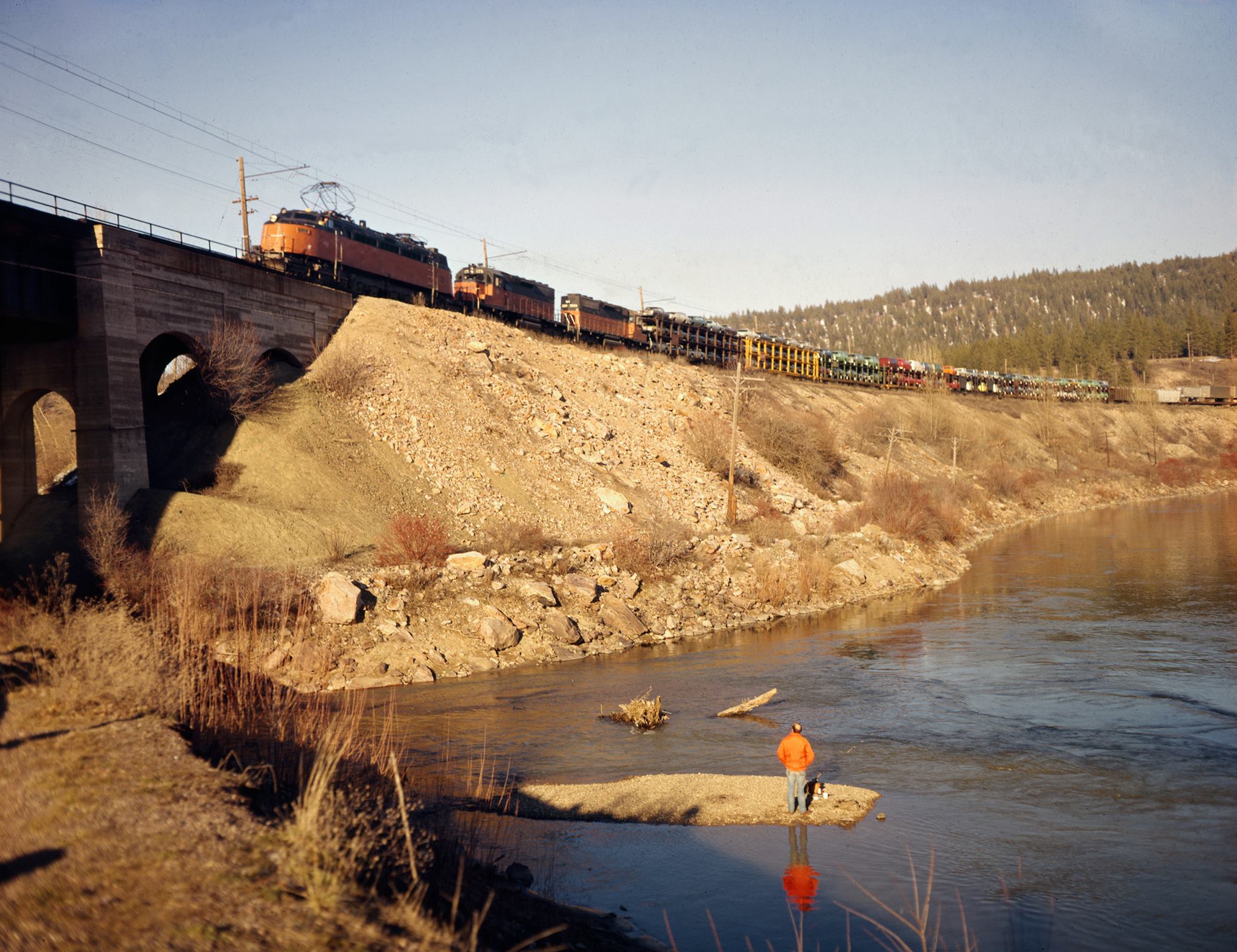

A fisherman casually watches Milwaukee Road's westbound time freight #261, led by a "Little Joe" and SD40-2's #175 and #3000, cross the Frontage Road overpass near the Clark Fork River at Nine Mile, Montana in 1973. Today, the abutments remain but the bridge has been removed. Ron Nixon photo.

A fisherman casually watches Milwaukee Road's westbound time freight #261, led by a "Little Joe" and SD40-2's #175 and #3000, cross the Frontage Road overpass near the Clark Fork River at Nine Mile, Montana in 1973. Today, the abutments remain but the bridge has been removed. Ron Nixon photo.Completion

Perhaps, though, most advantageous was the fact the railroad now could boast that it was the only true transcontinental whose own rails stretched from Chicago to Seattle (the Northern Pacific and Great Northern's lines reached only as far east as the Twin Cities meaning they had to transfer their traffic over to the CM&StP or ally Chicago, Burlington & Quincy for the rest of the journey).

Less than two months after the Extension was completed it opened to freight traffic on July 4, 1909. However, it wasn't until a year later on July 10, 1910 that the first passenger trains rolled over the new line.

In an attempt to compete with the GN and NP for dominance in the transcontinental passenger market the CM&StP unveiled their new heavyweight trains the Columbian and Olympian with the latter being the flagship of the fleet.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-20 and E-72 layover next to the roundhouse at Harlowton, Montana on May 7, 1958. At this time the E-20 (Class EP-4) was still regularly pulling the "Olympian Hiawatha." American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-20 and E-72 layover next to the roundhouse at Harlowton, Montana on May 7, 1958. At this time the E-20 (Class EP-4) was still regularly pulling the "Olympian Hiawatha." American-Rails.com collection.Electrification

Just a few years after the new transcontinental line had opened the CM&StP quickly discovered how difficult it was to operate trains through rugged mountain ranges, even on a route so well engineered, and decided in an unprecedented move to electrify significant sections of the route.

Thus, the legend of the Milwaukee Road was born. Construction on the first phase of electrification project began in 1914 at Harlowton, Montana and would reach into the northwestern region of Idaho at Avery.

This first section was completed in November, 1916, and in 1917 the railroad would also electrify its main line between Othello and Seattle, Washington with the final wires strung and completed by July of 1927 reaching Seattle Union Station in the downtown district of the city (this station was shared with Union Pacific and today still stands, restored).

There would remain a "gap" between Avery and Othello that would never be electrified, initially because the railroad just didn't have the money, even though it was often considered.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-70 leads an eastbound freight past the depot in Deer Lodge, Montana during August of 1965. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-70 leads an eastbound freight past the depot in Deer Lodge, Montana during August of 1965. American-Rails.com collection.For power the railroad used 110KV 3 phase AC transmission lines and converted this down to a 3,000-volt direct current (DC) system using motor generator sets located inside 22 line-side substations.

At the time and for many years the electrified western extension was the longest such freight operation in the world at 656 miles and ultimately a number of European countries would emulate the CM&StP's system.

Unfortunately for the railroad the western extension, including its electrification had come at an extremely heavy price of $257 million, more than four times the readjusted amount of $60 million in 1905. At the time freight volume had not been what the railroad expected and ultimately it was forced into bankruptcy in 1925.

A year

later it was sold and reorganized, and in 1927 renamed the Chicago,

Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as well as officially adopting its nickname as the Milwaukee Road.

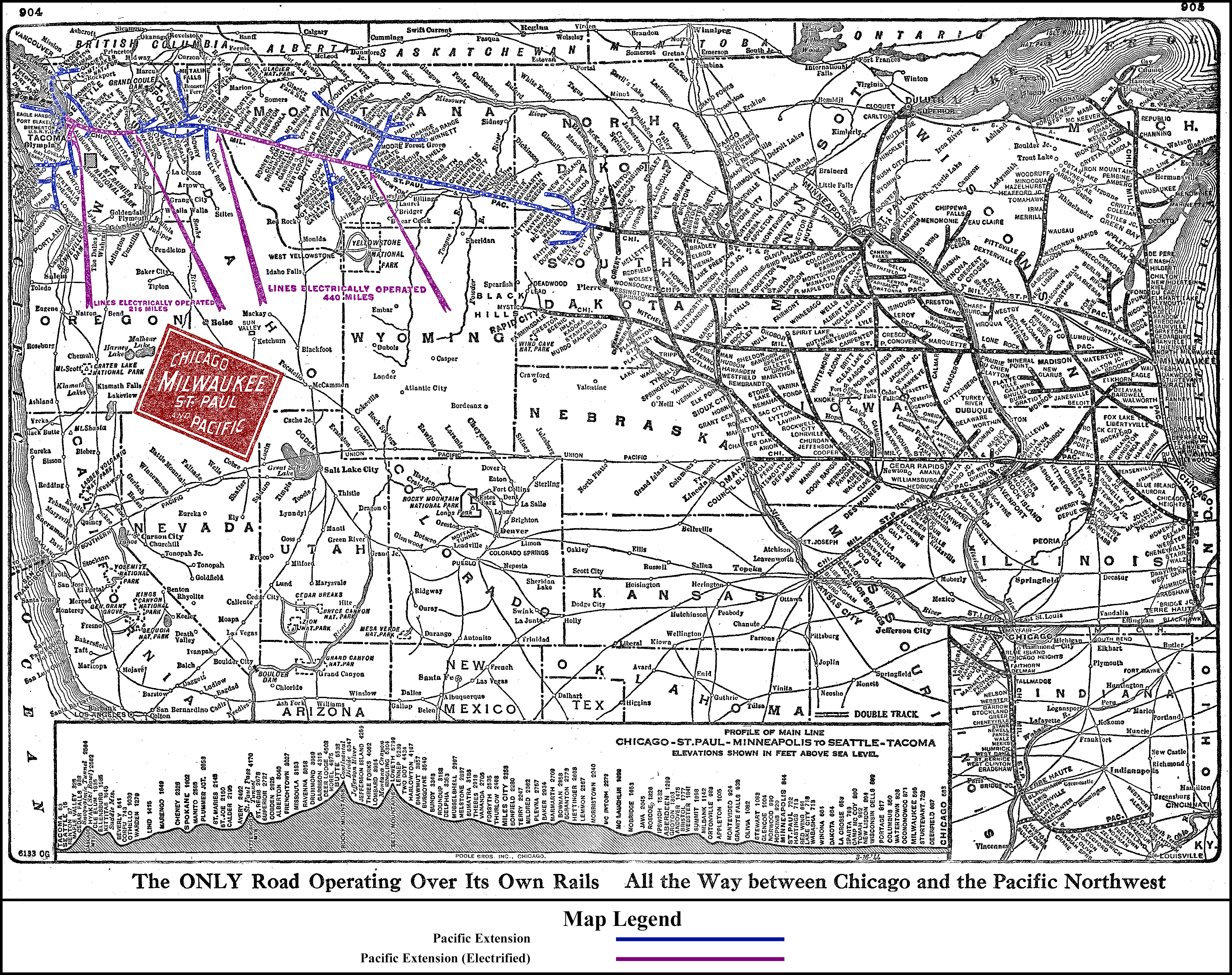

System Map (1944)

That year also saw the railroad open its own resort leading into the Yellowstone National Park in Gallatin Gateway, Montana called the Gallatin Gateway Inn, which would compete with what the Northern Pacific and Great Northern had to offer.

For power the Milwaukee Road used a number of different electric locomotives on the Extension including General Electric-built boxcabs (Class EP-1 and EF-1), the unique Bi-Polars (Class EP-2), rare Baldwin-Westinghouse Quills (Class EP-3 they were somewhat similar to boxcabs) and finally the last motors ever purchased the highly powerful (and popular) "Little Joes" (Class EP-4 and EF-4).

The Little Joes were purchased in the early 1950s to replace the Milwaukee Road’s aging fleet of electrics which consisted of elderly GE boxcabs; classes EP-1, EF-1, and EP-2 (Bi-Polars).

A pair of Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" and a GP9 lead time freight #264 along the Clark Fork River near Bearmouth, Montana on June 17, 1963. Ron Nixon photo.

A pair of Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" and a GP9 lead time freight #264 along the Clark Fork River near Bearmouth, Montana on June 17, 1963. Ron Nixon photo.The Bi-Polars enjoyed relatively long lives and were scrapped in 1962 while the original EP-1s and EF-1s were retired following the purchase of the EF-4s in 1950 (however, boxcab classes EF-2, EF-3, and EF-5 remained in service along with the Little Joes until the end).

While the Extension became an efficient and reliable main line, even after the CMStP&P's reorganization in the mid-1920s the route still failed to live up to expectations, particularly with the oncoming of the Great Depression in 1929. Even the surge of traffic during World War II was not enough for the railroad to stave off a second bankruptcy in 1945.

Interestingly, the best years of Lines West lay ahead. In 1947 the Milwaukee Road canceled the premier Olympian and inaugurated the posh Olympian Hiawatha between Chicago and Seattle.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-74 and E-20 were photographed here at Butte, Montana on May 9, 1962. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-74 and E-20 were photographed here at Butte, Montana on May 9, 1962. American-Rails.com collection.This train was custom-built by the railroad and featured the highly popular "Super Dome" and "Skytop" observation cars, which were hustled through Montana by matching Little Joe EP-4s and by boxcab EP-1s west of Othello, Washington. For reasons unknown (although the railroad claimed lack of ridership) the Milwaukee discontinued the Olympian Hiawatha by 1961.

However, in 1958 it began trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) or piggyback service between Seattle and Chicago, a move that would see the Pacific Coast Extension explode in traffic growth. Five years later in 1963 the railroad introduced its high-priority "XL Special" (westbound #261) and "Thunderhawk" (eastbound #262) scheduled freights.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-72, an FP45, and a pair of GP40's have priority freight #261 hustling westbound through rural Superior, Montana along the Clark Fork River on August 26, 1970. Ron Nixon photo.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-72, an FP45, and a pair of GP40's have priority freight #261 hustling westbound through rural Superior, Montana along the Clark Fork River on August 26, 1970. Ron Nixon photo.As traffic out of Seattle continued to increase through the 1960s and into the 1970s, so did the Milwaukee Road's share of this freight. The merger of Burlington Northern in 1970 played right into the railroad's hands giving it several new traffic interchange points.

During this time the CMStP&P essentially controlled the Port of Seattle as it commanded nearly 80% of its originating traffic and also held roughly 50% of the total container traffic originating from the Pacific Northwest in general.

In other words, the Milwaukee Road was completely dominating freight volume between Chicago and Seattle (the railroad could also shave almost a full day off transit times compared to that of the BN).

Death of a railroad... Contractors are scrapping the rails of Milwaukee Road's former Pacific Extension main line east of Alberton, Montana on July 9, 1982. Ron Nixon photo.

Death of a railroad... Contractors are scrapping the rails of Milwaukee Road's former Pacific Extension main line east of Alberton, Montana on July 9, 1982. Ron Nixon photo.Decline

The demise of the Milwaukee Road had already begun, however. Top management at the time had all but given up on wanting to run a railroad. In 1972 it decided to discontinue (but not scrap) electrified operations on the Coast Division between Othello and Seattle.

Then, in 1974 the railroad canceled its electrification completely running its final Little Joes in June of 1974 between Harlowton, Montana and Avery, Idaho. Maintenance of the route was all but halted through the 1970s and 10 mph slow orders were rampant during the line's final years.

By 1977 the very poorly managed Milwaukee Road entered bankruptcy and in a stunning move made two years later, decided to scrap its entire Extension west of Terry, Montana, some 1,100 miles of track.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-70 and a trio of SD40-2's have a time freight heading westbound over Pipestone Pass (Montana) on June 17, 1973. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-70 and a trio of SD40-2's have a time freight heading westbound over Pipestone Pass (Montana) on June 17, 1973. American-Rails.com collection.Abandonment

And so, as Michael Sol notes, at 8:47 PM on March 15, 1980 the final dead freight east, Extra 5802 (led by U36C #5802) departed eastbound from Tacoma, Junction, Washington.

The trip was well-documented, especially by a group of dedicated railfans which took a series of memorable images of the train slowly trudged its way along the decaying railroad. Ironically, the best engineered line through the northern Rockies is the only such route to ever be formally abandoned.

Today, much of the original right-of-way through Montana, Idaho, and Washington remains in place although it is now owned by locals save for small stretches in Idaho and virtually all of the line through Washington (which is owned by the state).

Why Abandonment?

Why was the Milwaukee Road's Lines West abandoned and why did the railroad fail? Much of it can be explained in mismanagement following its 1925 bankruptcy, which is partially covered at the Milwaukee Road article.

In addition, the then-Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (or simply the "St. Paul") was undercut in its attempt to build the Pacific Extension by E.H. Harriman and Northern Lines interests, which acquired most of the necessary property along the route between Montana and Washington.

The group then resold the land to the railroad at inflated prices, driving up the final cost from the expected $50 million, to $250 million. This factor, coupled with financial mishandling of the project and a decision to electrify the line when officials were already well-aware of the Pacific's Extension astronomical cost, resulted in the once-prosperous St. Paul road into bankruptcy by 1925.

The receivership then allowed vultures, like the private banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb to slowly gain control of the railroad and bleed the company of cash for more than a decade before finally losing their grip when the system entered its second bankruptcy in 1935.

Unfortunately, the company's plight only slightly improved from a managerial standpoint at this time as the company's incompetent board still remained in control after the 1945 receivership, which more or less continued through the 1977 bankruptcy.

In general, management ineptness dating back generations can explain the railroad's failure. Thomas Ploss, in his excellent book "The Nation Pays Again," explains one such incomprehensible blunder:

"The transcontinental line was owned outright by the Milwaukee Road except for the 30-mile Pacific Coast Railroad that lay between the Cascade Range and Seattle, the last mountain range westbound from Chicago.

This little line had been built for logging and speculative purposes late in the 19th century and when 'The St. Paul' indulged in its dreams of empire conveniently provided a leased access to Seattle's deepwater port without the necessity of building a new line down the slope.

Soon the lumber in the area was logged off...and thereafter the Pacific Coast Railroad's business was 90% that of its tenant, which became the Milwaukee Road.

Pacific Coast's lease with the Milwaukee Road provided that the railroad with most usage of the line shown by counting railroad wheels would be taxed with the proportionate amount of maintenance expense. Thus, Milwaukee Road paid for 90% of the maintenance.

The Pacific Coast Railroad's management sometime in the late 1920s reorganized itself into a subsidiary of a holding company and advertised the railroad for sale beginning in 1930.

For twenty years the line remained unsold. Then, on June 30, 1950, Great Northern Railroad paid $100 for an option to buy Pacific Coast Railroad's shares for $1.7 million on terms of nine annual installments at 3% annual interest, or about the same that the Crowley management had committed itself to pay for but one train of 'Olympian Hiawatha' rolling stock in 1947.

When Great Northern's purchase application came before the ICC, that body recorded Milwaukee Road Western Counsel Lutterman as making no representation whatever to protect his client's interest in preserving its sole ownership of the line passing into the hands of a hostile competitor.

For 30 years thereafter, until abandonment day in 1980, the Milwaukee Road paid 90% or more of the maintenance costs of this little line - and used that fact to justify its application to abandon its entire transcontinental line." (Emphasis added.)

Incredible...

Photo Gallery

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-74 and GP40 #17 lead an eastbound freight past the beautiful station in Missoula, Montana during the summer of 1973. Today, the building is preserved and still looks much the same as it did in this photo; even the station placards are proudly displayed in their original locations. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-74 and GP40 #17 lead an eastbound freight past the beautiful station in Missoula, Montana during the summer of 1973. Today, the building is preserved and still looks much the same as it did in this photo; even the station placards are proudly displayed in their original locations. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-20 has the "Olympian Hiawatha" boarding at the beautiful depot in Butte, Montana, circa 1951. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-20 has the "Olympian Hiawatha" boarding at the beautiful depot in Butte, Montana, circa 1951. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-79 and E-73 have an eastbound freight extra at the yard in Deer Lodge, Montana on October 2, 1959. Note steeple-cab switcher E-82. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" E-79 and E-73 have an eastbound freight extra at the yard in Deer Lodge, Montana on October 2, 1959. Note steeple-cab switcher E-82. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-71, along with SD40-2s #3038, #3024, an #3026 leads a westbound freight over the Clark Fork River and Northern Pacific main line at St. Regis, Montana in September of 1972. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-71, along with SD40-2s #3038, #3024, an #3026 leads a westbound freight over the Clark Fork River and Northern Pacific main line at St. Regis, Montana in September of 1972. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road switcher E-80 totes a single caboose through the yard at Butte, Montana on August 24, 1972. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road switcher E-80 totes a single caboose through the yard at Butte, Montana on August 24, 1972. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road shop goat x3800 was photographed here between assignments in Deer Lodge, Montana on July 11, 1972. The little home-built switcher, powered by a 220-volt DC extension cord, spent many years pulling electrics into and out of the yard's roundhouse. Today, it sits on display in Harlowton, Montana. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road shop goat x3800 was photographed here between assignments in Deer Lodge, Montana on July 11, 1972. The little home-built switcher, powered by a 220-volt DC extension cord, spent many years pulling electrics into and out of the yard's roundhouse. Today, it sits on display in Harlowton, Montana. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road steeple-cab switcher E-81 is seen here in Deer Lodge, Montana, circa 1964. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road steeple-cab switcher E-81 is seen here in Deer Lodge, Montana, circa 1964. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. A set of new Milwaukee Road SD40-2s, led by #197 and #196, are seen here near Superior, Montana in the fall of 1974 following the discontinuance of electrified operations. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A set of new Milwaukee Road SD40-2s, led by #197 and #196, are seen here near Superior, Montana in the fall of 1974 following the discontinuance of electrified operations. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-78 awaits an eastbound departure from the depot in Avery, Idaho on August 19, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-78 awaits an eastbound departure from the depot in Avery, Idaho on August 19, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. A pair of Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" lead eastbound freight #263 through Montana's Silver Bow Canyon on June 2, 1972. A Burlington Northern freight can be seen in the foreground. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Milwaukee Road "Little Joes" lead eastbound freight #263 through Montana's Silver Bow Canyon on June 2, 1972. A Burlington Northern freight can be seen in the foreground. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection. Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-79 and a trio of GP40s throttle up as they depart Butte, Montana with an eastbound freight in August, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Milwaukee Road "Little Joe" E-79 and a trio of GP40s throttle up as they depart Butte, Montana with an eastbound freight in August, 1969. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.Sources

- Murray, Tom. Milwaukee Road, The. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2005.

- Ploss, Thomas. Nation Pays Again, The. Ploss (Self Published): January, 1985.

- Scribbins, Jim. Hiawatha Story, The. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road Remembered. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota, 2008 (Second Edition).

- Sol, Michael (Milwaukee Road Archives)

- Solomon, Brian and Gruber, John. Milwaukee Road's Hiawatha's, The. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2006.

- Wood, Charles R. and Wood, Dorothy M. Milwaukee Road West. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1972.