New York, Ontario & Western Railway: Map, Roster, History

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The New York, Ontario and Western Railway is a sometimes

forgotten fallen flag because it exited the business even prior to the mega merger movement.

The NYO&W suffered a rather unsuccessful and sad existence throughout most of the 20th century as it attempted to stay solvent.

Because of its financial struggles the Ontario & Western was given several unflattering nicknames, such as the "Old & Weary," although it did its best to survive after its main source of traffic, anthracite coal, dried up.

The railroad was conceived just after the Civil War and eventually opened a rugged route from New York City to Lake Ontario with a principal branch to Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Following its loss of coal the company attempted to market itself as a merchandise, bridge carrier but continued to struggle in the postwar years. Alas, following two decades mired in bankruptcy, from which it never emerged, the O&W was ordered to liquidate in the late 1950s.

Photos

New York, Ontario & Western FT's await their fate at the yard in Middletown, New York during May, 1957. Doug Wornom photo.

New York, Ontario & Western FT's await their fate at the yard in Middletown, New York during May, 1957. Doug Wornom photo.History

There have been many writings over the years concerning the history of the New York, Ontario & Western and most have not been particularly flattering. Even during the company's existence it was mocked in financial circles, regarded as the "Old Woman."

It was viewed as a worn down property with an unlikely future. Perhaps a Wall Street investor stated it best in an article by A.V. Neusser and C.E. Pearce entitled, "The NYO&W," from the August 1942 issue of Trains Magazine:

"I must confess I cannot understand why some railroads were built...We will take, for example, the New York, Ontario & Western.

At A Glance

Weehawken, New Jersey - Cornwall, New York (trackage rights, West Shore Railroad) Cornwall - Campbell Hall - Oneida - Oswego, New York Summitville - Kingstown Cadosia, New York - Scranton, Pennsylvania (Scranton Division) Summitville - Port Jervis - Monticello Sidney - Edmeston, New York (New Berlin Branch) Randallsville - Utica (Utica Division) Clinton - Rome, New York | |

This road really starts nowhere, goes nowhere, avoids all large industrial centers, and ends nowhere. When its anthracite mines folded up, the earnings of the road fell off so rapidly that serious financial difficulties soon developed..."

Despite its many issues, operationally the railroad was a fascinating system serving local customers within bucolic settings that defines the industry's classic era.

The NYO&W began life as the New York & Oswego Midland Railroad, envisioned by Dewitt C. Littlejohn to open the state's northerly interior by tapping its natural and agricultural resources.

An A-B set of New York, Ontario & Western FT's and F3's head east through Campbell Hall, New York, circa 1953. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

An A-B set of New York, Ontario & Western FT's and F3's head east through Campbell Hall, New York, circa 1953. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.At the time this area offered little rail service and no carrier here provided a direct link to New York City. The NY&OM was incorporated in 1868 and began construction westward from Middletown, New York.

For whatever reason, instead of following river valleys and easier grades, Littlejohn felt his line should be constructed across a series of mountain ranges and valleys, which bisected at right angles to the direction of the railroad.

This required numerous fills, bridges, and tunnels. After the road was completed, many described it as the "Colorado Midland" of the east.

The CM, which eventually became part of the Rio Grande, was built during the 1880s and opened a rugged route across the Colorado Rockies from Colorado Springs and Leadville to Glenwood Springs and Grand Junction via Hagerman Pass.

The great expense incurred on the NY&OM's construction resulted in its bankruptcy and it was reorganized in 1880 as the New York, Ontario and Western Railway. By this time it had completed a main line from Middletown to Oswego along the banks of Lake Ontario where port services were established.

Logo

Expansion

In addition, the O&W inherited branches to Delhi, New Berlin and Ellenville, New York. Its most important segment was located east of Middletown through association with the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railway.

The NYWS&B maintained a route between Cornwall and Weehawken, New Jersey (just north of Jersey City), extending north to Albany, then turning west all of the way to Buffalo. The project was largely spearheaded by the same folks overseeing the O&W and enabled it to reach Weehawken, via 52 miles of NYWS&B trackage rights.

The West Shore had completed a connection from its main line at Cornwall to the O&W at Middletown in 1883, permitting the latter to achieve a more direct routing to the New York City region. The New York Central & Hudson River eventually acquired control of the NYWS&B in 1885, renaming it as the West Shore Railroad.

The Central continued allowing the O&W access to Weehawken, in which it paid a fixed sum per mile. The so-called "Middletown Branch" of the former NYWS&B was sold to the O&W and in 1886 a new agreement was reached with the West Shore for trackage rights lasting 200 years.

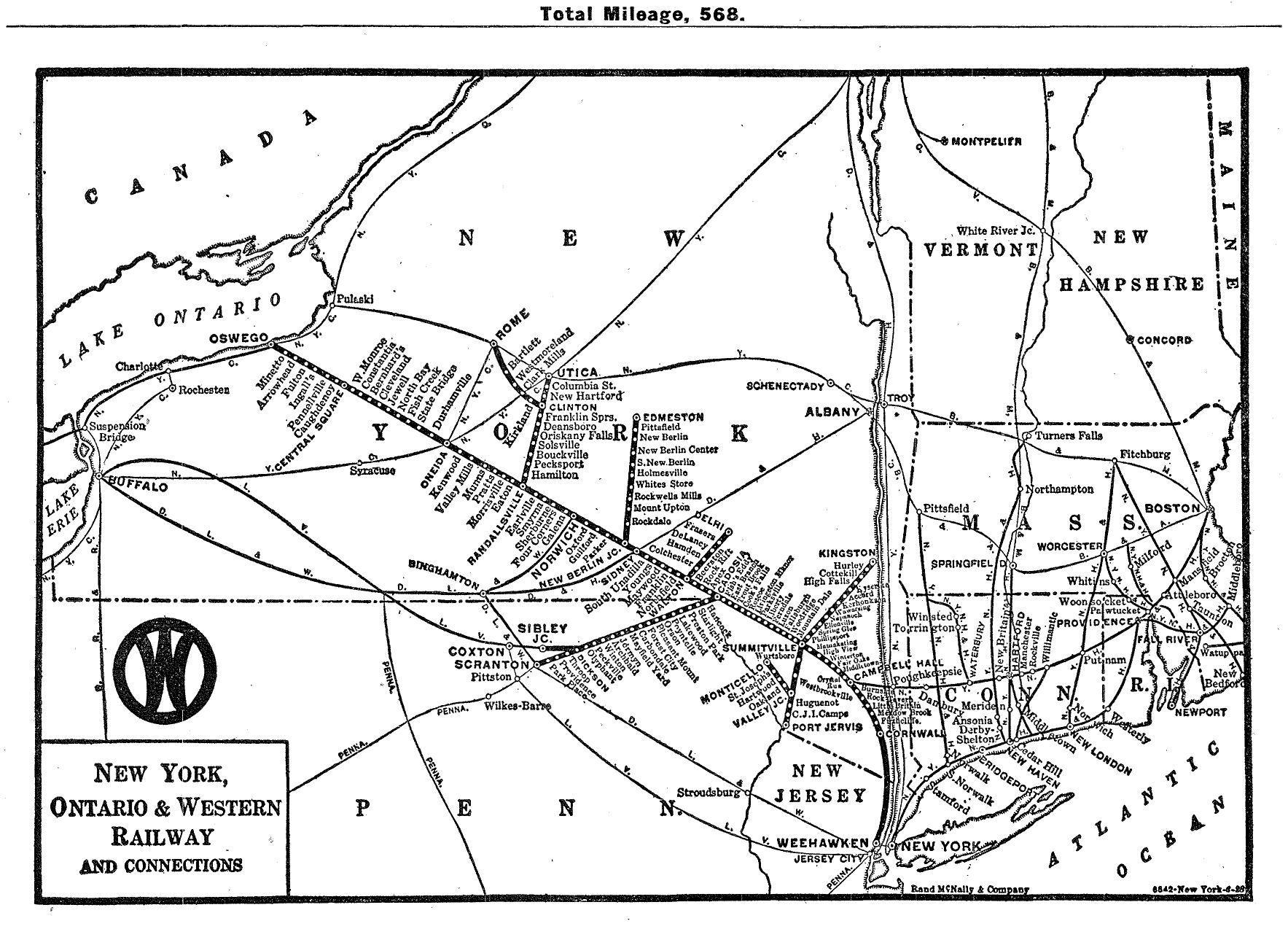

System Map (1940)

As part of this deal, the O&W was also granted use of the West Shore's terminal facilities in Weehawken. Its entire main line, including trackage rights, stretched 326 miles between New York and Oswego while the road's primary shops were situated in Middletown.

There were four divisions; the Southern Division ran from Weehawken/Cornwall to Sidney, a distance of 201 miles (Comprised within this territory is trackage of the ex-Port Jervis, Monticello & Summitville Railroad running from the main line at Summitville to Port Jervis, 22 miles, and a branch from Valley Junction to Monticello extending 16 miles.

In addition:

- A 35-branch to the north of Summitville connected with the Ulster & Delaware/NYC at Kingston.)

- The 125-mile Northern Division continued north to Oswego (This corridor also included the New Berlin Branch running 29 miles to Edmeston until it was sold to the Unadilla Valley Railway.)

- The Utica Division branched from the main line at Randallsville and ran 31 miles to Utica where connections were made with the NYC and Lackawanna (there was also a 13-mile branch to Rome from a location known as Rome Branch Junction).

- Finally the Scranton Division. This corridor proved of vital importance as it would generate all of the O&W's lucrative anthracite coal traffic.

A rare color photo of New York, Ontario & Western FT's in storage on the Erie Railroad during the summer of 1957. Following the shutdown, the FTs remained here until 1967 when most were acquired by the New York Central as trade-in units on new GP40s. In addition, four other units, an A-B-B-A set, were sold to the B&O (#806-807, 806B-807B). Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A rare color photo of New York, Ontario & Western FT's in storage on the Erie Railroad during the summer of 1957. Following the shutdown, the FTs remained here until 1967 when most were acquired by the New York Central as trade-in units on new GP40s. In addition, four other units, an A-B-B-A set, were sold to the B&O (#806-807, 806B-807B). Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.The line was completed in 1890 during the presidency of Thomas P. Fowler, who had arrived from the New York Central. The corridor ran 54 miles from the main line at Cadosia to Scranton and a connection with the Central Railroad of New Jersey, Lackawanna, and Lehigh Valley.

The O&W became a modestly successful operation with its transportation of milk and dairy products along with very popular seasonal trains to resorts and hotels situated within the lower Catskill Mountains. However, no other railroad depended on the movement of anthracite quite as much as the Ontario & Western.

Prior to wide-scale use of petroleum products, anthracite was a popular and important source of heating fuel for residential and commercial sectors since it burned very cleanly.

At the turn of the 20th century the profitable 568-mile O&W even had the means of double-tracking its Southern Division from East Branch to Cornwall, as well as the entirety of the Scranton Division.

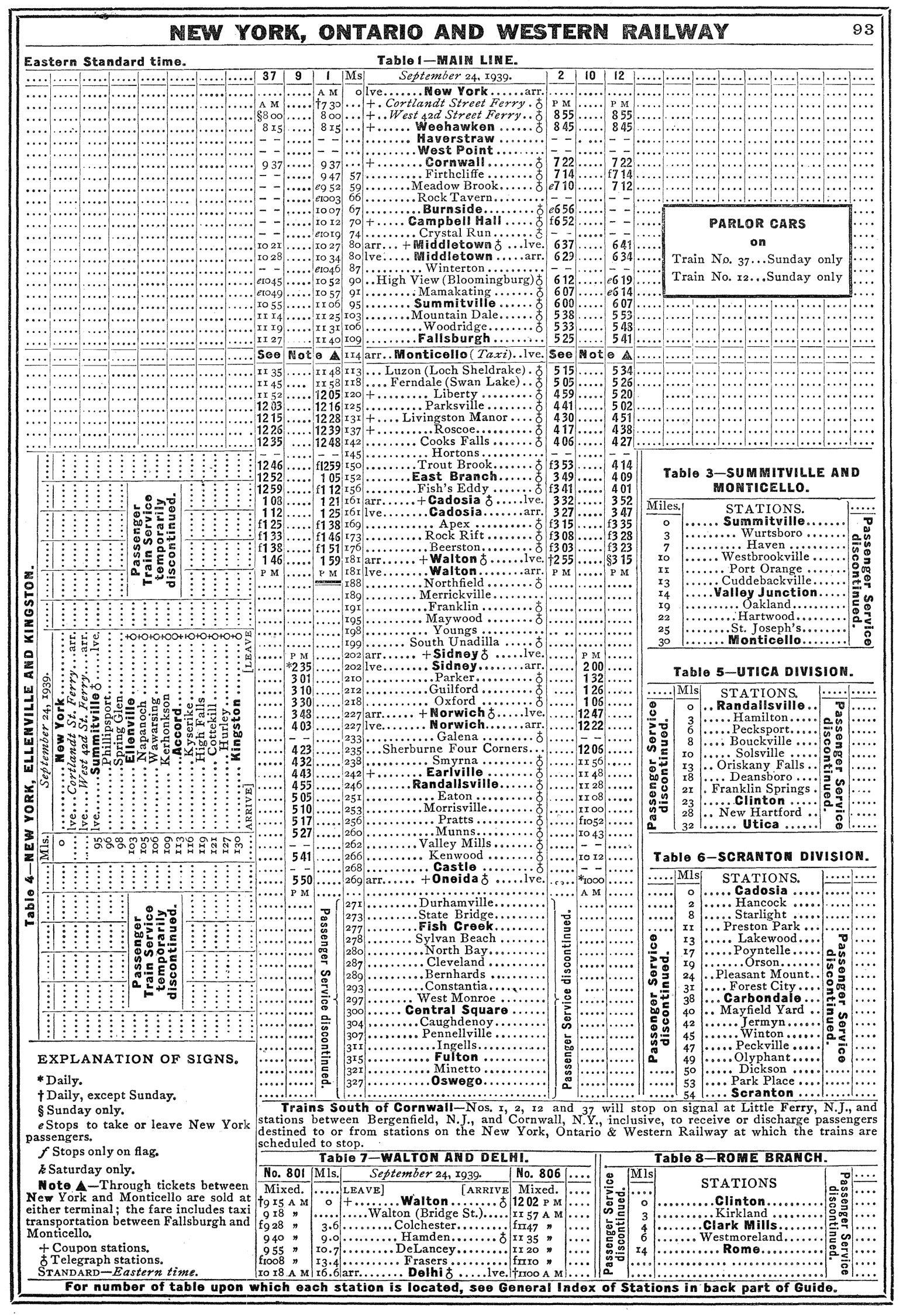

Timetables (1940)

It even upgraded the latter corridor with block signals and had centralized traffic control (CTC) installed from East Branch to Cadosio (8 miles).

Unfortunately, the first wave of bad luck hit in October of 1904 when it came under the control of the New York, New Haven & Hartford, then led by banker and industrialist J.P. Morgan.

A new president was brought in, Charles Mellen, who attempted to use the O&W as a bartering chip with the New York Central to leverage the New Haven's interests elsewhere.

This endeavor proved unsuccessful for the New Haven but resulted in the railroad being neglected and poorly maintained. The next setback was the onset of better roads and highways constructed into upstate New York.

A pair of Ontario & Western observation cars, a steam generator car, and F3A #502 have an inspection train at Middletown, New York in March, 1957. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Ontario & Western observation cars, a steam generator car, and F3A #502 have an inspection train at Middletown, New York in March, 1957. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.These infrastructure improvements allowed folks much more freedom to reach the mountains on their own accord; over time the automobile severely eroding the O&W's once-lucrative passenger traffic. Finally, as the 1920s dawned anthracite coal began losing its appeal as a primary heating source.

While it still remained in demand for another few decades the natural resource was simply no longer profitable by the postwar years.

The new highways also hammered its lucrative milk traffic and the economic downturn of the 1930s, brought about by the stock market crash in October of 1929, painted a bleak picture for the road's future.

"Mountaineer Limited" (Streamliner)

It is surprising that of all the railroads to dabble in streamlining, the financially strapped Ontario & Western was one to do so.

Surprisingly, some larger railroads did not even bother with the concept, believing it a gimmick, while others, like the very profitable Southern Railway, only spent conservatively on the styling.

The O&W embarked on such a program in 1938 to update its Mountaineer Limited, a train which traversed 137 miles from Weehawken to Roscoe, New York.

The railroad hired noted industrial designer Otto Kuhler to overhaul two steel parlor-observation cars and a handful of coaches with updated interior decors and matching styling inside and out.

In addition, 4-8-2 #405, a 1923 product of Alco's Schenectady Works (classed Y-1), was dressed in a light streamlining (or "speedlined") with a livery of maroon, orange, and black carrying elements of chrome.

According to the article by A.V. Neusser and C.E. Pearce it appears the road cut short further streamlining efforts although perhaps this was for the best as passenger earnings continued to slump regardless.

The result of these setbacks resulted in the O&W's traffic slashed in half by 1932 from its peak three years earlier according to Robert Malinoski's article, "NYO&W Scranton Division: March 17, 1933," published in the March, 1987 issue of Trains Magazine.

During February of 1937 the New York, Ontario & Western entered voluntary bankruptcy from which it would never emerge.

The company, however, did not give up easily. Its loyal and hardworking employees tried a myriad of things to pull the railroad out of its financial crisis. One of its first tactics was the aforementioned streamlining concept on the Mountaineer to bring back passenger traffic.

It then touted itself as a bridge line the railroad began launching merchandise freights from Mayfield Yard in Scranton to the New Haven at Maybrook Yard.

These symbol-freights included eastbound OB-2 and LB-4 while their westbound counterparts were BO-1 and BL-1. The O&W also operated similar trains between Scranton and Norwich/Utica including SU-1 and US-2.

The company also tried to prop up its port at Oswego to lure Canadian National and Canadian Pacific to initiate carferry services across the lake.

It spent around $300,000, an incredible amount of money for a struggling road of its size, to improve its port facilities. Alas, neither of the Canadian roads expressed much interest in the joint service.

Steam Roster

| Class | Road Numbers | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Completion Date | Engine Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 225-228 | 4-6-0 | Alco (Brooks) | 1911 | 4 |

| I | 42 | 2-6-0 | Baldwin | 1907 | 1 |

| I-1* | 33, 35 | 4-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1904 | 2 |

| L | 50-52 | 0-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1910 | 3 |

| L | 53-56 | 0-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1911 | 4 |

| P | 201-204 | 2-8-0 | Cooke | 1900 | 4 |

| P | 205 | 2-8-0 | Cooke | 1901 | 1 |

| P | 207-211 | 2-8-0 | Cooke | 1901 | 5 |

| P | 213-214 | 2-8-0 | Cooke | 1901 | 2 |

| P | 215, 217 | 2-8-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1902 | 2 |

| P | 218-220 | 2-8-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1903 | 3 |

| U | 254-255 | 2-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1907 | 2 |

| U-1** | 244-246 | 4-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1904 | 3 |

| U-1** | 250 | 4-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1905 | 1 |

| U-1** | 251, 253, 256 | 4-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1907 | 3 |

| V | 271-275 | 2-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1908 | 5 |

| V | 277-280 | 2-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1908 | 4 |

| V | 281-282, 284 | 2-6-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1909 | 3 |

| W | 301-314 | 2-8-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1910 | 14 |

| W | 315-326 | 2-8-0 | Alco (Cooke) | 1911 | 12 |

| X | 351-356 | 2-10-2 | Alco | 1915 | 6 |

| X | 358-362 | 2-10-2 | Alco | 1915 | 5 |

| Y | 401, 403-410 | 4-8-2 | Alco | 1922-1923 | 9 |

| Y-1*** | 402 | 4-8-2 | Alco | 1922 | 1 |

| Y-2**** | 451-460 | 4-8-2 | Alco | 1929 | 10 |

* Built as 2-6-0s, later converted to 4-6-0's in 1919-1920.

** Built as 2-6-0s, later upgraded to 4-6-0's between 1916 - 1924.

*** Upgraded with booster; tractive effort increased from 50,300 to 60,600 pounds. In addition, weight increased from 158 to 162.5 tons.

**** Additional tractive effort improvements to 71,850 pounds; weight was also increased from 158 to 179.5 tons.

"C" - Designates a "Camelback" design.

All of the above information concerning the O&W's steam locomotive roster is courtesy of the A.V. Neusser and C.E. Pearce article entitled, "The NYO&W," from the August 1942 issue of Trains Magazine.

Diesel Roster

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| NW2 | 111-131 | 1948 | 21 |

| F3A | 501-503, 821-822 | 1948 | 5 |

| FTA | 601, 801-808 | 1945 | 9 |

| FTB | 601B, 801B-808B | 1945 | 9 |

| F3B | 821B-822B | 1948 | 2 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 101-105 | 1942 | 5 |

Ontario & Western FT's sit under the coaling tower at Middletown, New York in the late fall of 1947. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Ontario & Western FT's sit under the coaling tower at Middletown, New York in the late fall of 1947. Marvin Cohen photo. American-Rails.com collection.Final Years

Finally, it traded in aging steam locomotives for new Electro-Motive FT's and F3's between 1945 and 1948, aided here by Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) loans.

According to the article, "Obituary Of An Old Woman," by authors Jim Shaughnessy and Rod Craib from the July, 1957 issue of Trains, in a last ditch effort the company eliminated most of its double-tracking with automatic block signals and tried any means necessary to acquire new customers.

It discontinued seasonal passenger service in 1948 and ended all passenger trains after September 10, 1953. Alas, the 1950s simply proved an impossible decade. In 1936 it was still handling 6 million tons of anthracite but this number had declined to only 307,521 tons by 1955.

As the trustees realized the company's future appeared doomed they made one last attempt to keep segments operating by having interested parties purchase various routes. Unfortunately, the talks dragged out and creditors grew increasingly impatient to sell off the assets and recover their losses.

Realizing the unrest, the bankruptcy court ordered the O&W

liquidated and its assets sold on March 29, 1957. It was the largest liquidation of its day until the Rock Island met a similar fate in 1980.