New Haven Railroad: Rosters, Map, Logo, History, Trains

Last revised: October 14, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Perhaps no other major railroad served the public like the New Haven. The system sprawled its way across the heart of New England, derived a considerable percentage of its annual revenue through the movement of passengers, and was the only direct service between New York and Boston.

Many thousands of commuters depended on the New Haven everyday. The company's complete name was the New York, New Haven & Hartford (or NYNH&H) with its history a dizzying array of subsidiaries and predecessors.

At its peak it operated a dense network of nearly 2,000 routes miles concentrated in just four states. In the end, poor management and sagging traffic would cost the company, forcing it into bankruptcy during the early 1960s.

In an interesting twist as a condition of the ill-fated Penn Central union the destitute New Haven was included in the merger per a ruling by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

Alas, PC failed within a few years and later disappeared into government-sponsored Conrail. Today, large segments of the New Haven's light density branch lines have been abandoned although its key New York-Boston main line remains an integral part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.

Photos

New Haven boxcabs #83 (EF-1) and #0114 (EF-2) were photographed here at the Van Nest Shops in the Bronx, circa 1955. Meyer Pearlman photo. By the date of this photo the former unit was out-of-service following a derailment at Oak Point Yard (subsequent damage by a crane attempting to re-rail it severely damaged the roof overhang and it never returned to service) while the latter unit was being used as a power station to turn the 11,000-volt AC transmission into 600-volt DC for testing the third rail shoes. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven boxcabs #83 (EF-1) and #0114 (EF-2) were photographed here at the Van Nest Shops in the Bronx, circa 1955. Meyer Pearlman photo. By the date of this photo the former unit was out-of-service following a derailment at Oak Point Yard (subsequent damage by a crane attempting to re-rail it severely damaged the roof overhang and it never returned to service) while the latter unit was being used as a power station to turn the 11,000-volt AC transmission into 600-volt DC for testing the third rail shoes. American-Rails.com collection.History

The history of the storied New Haven system is a long list of predecessors which trace back to the 1830s. As Mike Schafer notes in his book, "More Classic American Railroads," in total more than 200 small railroads came together to form the modern-day New York, New Haven & Hartford.

These many mergers and takeovers helped create the only high-speed route from Boston to New York although in several ways it was all about power and monopolistic control.

At A Glance

New York City (Grand Central Terminal) - New Haven, Connecticut - New London, Connecticut - Providence, Rhode Island - Boston New York City (Pennsylvania Station) - New Rochelle, New York New Haven - Hartford, Connecticut - Springfield, Massachusetts New Haven - Middletown - Putnam, Connecticut - Readville (Boston) New Haven - Northampton/Holyoke, Massachusetts - Winsted, Connecticut Waterbury - Hartford - Plainfield, Connecticut - Providence Providence - Worcester, Massachusetts Norwalk, Connecticut - Pittsfield, Massachusetts Derby, Connecticut - Campbell Hall/Beacon, New York New London - Worcester New Bedford/Fall River - Framingham - Lowell/Fitchburg, Massachusetts Boston - Brocton - Provincetown Buzzards Bay - Woods Hole Attleboro - Taunton - Middleboro, Massachusetts South Braintree - Plymouth, Massachusetts |

|

Diesel: 381 Electric: 22 | |

Freight Cars: 6,925 Passenger Cars: 1,055 | |

By the end of the 19th century the New Haven dominated the transportation market across southern New England and its only true competitor was the New York Central's Boston & Albany.

It also attempted to corner the market in northern New England although this scheme ultimately failed. A study of the New Haven's predecessors in great detail would probably cause many readers' eyes to glaze over and only a brief synopsis of its heritage will be provided here.

New Haven's train #5, the "John Quincy Adams," arrives in New York at 210th Street in the Bronx during the fall of 1957. This Talgo trainset was manufactured by American Car & Foundry with the locomotives produced by Fairbanks-Morse (P-12-42). The lightweight streamliner, with a locomotive perched at each end to avoid turning the train, was not successful as passenger complained of a rough ride. It was pulled from service on June 5, 1958 and later sold to Ferrocarril de Langreo of Spain in 1962. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven's train #5, the "John Quincy Adams," arrives in New York at 210th Street in the Bronx during the fall of 1957. This Talgo trainset was manufactured by American Car & Foundry with the locomotives produced by Fairbanks-Morse (P-12-42). The lightweight streamliner, with a locomotive perched at each end to avoid turning the train, was not successful as passenger complained of a rough ride. It was pulled from service on June 5, 1958 and later sold to Ferrocarril de Langreo of Spain in 1962. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.The New Haven Railroad’s immediate predecessors were the Hartford & New Haven (H&NH) and the New York & New Haven (NY&NH). The H&NH was the very earliest component, chartered in 1833 to connect its namesake cities.

The system began construction in 1836 and was completed in 1839. According to John Weller's book, "The New Haven Railroad: Its Rise And Fall," the grandfather of John Pierpont "J.P." Morgan, noted American banker and industrialist, was an investor in the H&NH.

J.P. would eventually hold considerable control of the New Haven while also maintaining interests in several other large railroads. The nearby NY&NH was built to connect its two namesake cities, chartered on June 20, 1844.

It began construction in 1848 and, according to the book, "New Haven Passenger Trains," by Peter Lynch, opened from Woodlawn in the Bronx (New York City) to New Haven, Connecticut during January of 1849.

Through a 12-mile trackage rights agreement with the New York & Harlem (later New York Central) the road provided service into downtown Manhattan.

Logo

Expansion

The two became natural merger partners and formally joined on July 24, 1872 to create the historic New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. By this date it already controlled what would become a key component of its Boston-New York corridor, the Shore Line Railway, when it was leased by the NY&NH on November 1, 1870.

This important predecessor carried a history dating back to the New Haven & New London of 1848, which became the Shore Line Railway in 1864 through a series of takeovers and leases. It hugged the north shore of Long Island Sound from New Haven to New London and under the NYNH&H became part of its "Shore Line Division."

By 1872 the railroad maintained a network stretching from New York to New London with a branch to Hartford via New Haven. From this point it would continue to expand by acquiring other smaller lines, eventually stretching out across most of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and southern Massachusetts.

A New Haven FA-FB-FA set lays over in Worcester, Massachusetts during May of 1962. American-Rails.com collection.

A New Haven FA-FB-FA set lays over in Worcester, Massachusetts during May of 1962. American-Rails.com collection.Its first major acquisition involved the purchase of the so-called "Air Line" in 1882. This company carried a long history, originally known as the New York & Boston Railroad chartered in 1846, to provide the shortest rail route, or "air line," between those two cities.

The city of Middletown, Connecticut notes in an essay of their town's heritage that the system was reorganized as the New Haven, Middletown & Willimantic Railroad in 1867.

It ran from a connection at New Haven to Willimantic, opening for service on April 25, 1873, according to an essay by Philip Blakeslee entitled, "A Brief History Of Lines West: The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad Company."

The well-engineered NHM&W was expensive to build although it offered a 25-mile shorter route to Boston than the Shore Line's. It ultimately failed and was reorganized as the Boston & New York Air-Line Railroad. The B&NYA-L went on to join the much larger New York & New England, a future New Haven property.

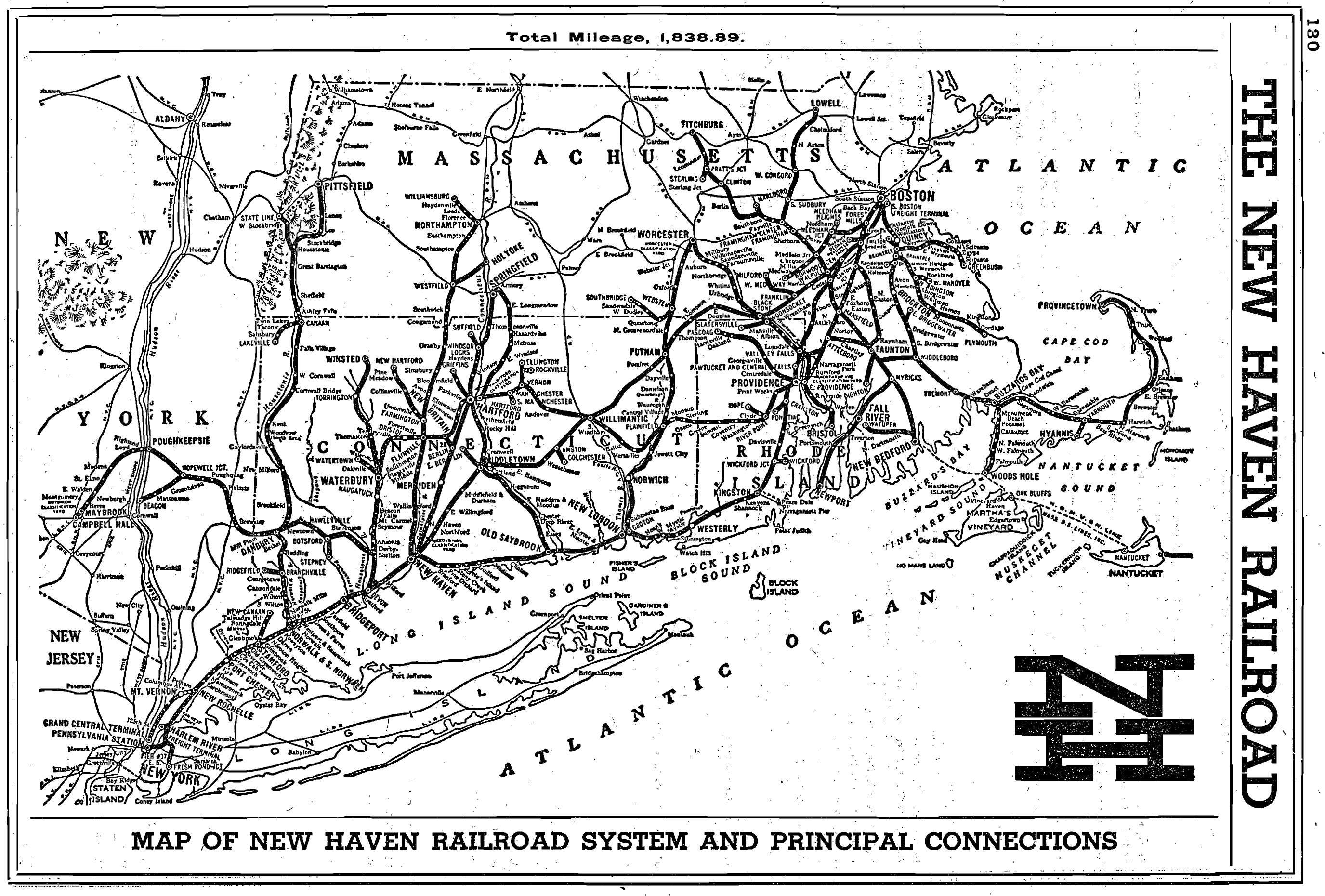

System Map (1952)

The NY&NE is another road whose history could fill a book. The New Haven gained full control in 1898, providing it with a significant reach across New England; the NY&NE stretched from Beacon, New York to Hartford, Connecticut; Providence, Rhode Island; and Boston via Willimantic and Franklin.

Prior to this event the New Haven had already added other important portfolios:

- In 1887 it acquired the New Haven & Northampton which utilized the former tow path of the Farmington Canal between New Haven and Northampton, Massachusetts via Farmington and Westfield (it also opened branches to North Hartford and Holyoke)

- Also in 1887 the Naugatuck Railroad was acquired running from Devon along the Shore Line to Winstead via Waterbury

- In 1892 the Housatonic Railroad joined the system as its western-most northerly branch, running from South Norwalk, Connecticut to Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- Also in 1892 the New York, Providence & Boston, better known as the "Stonington Line," was acquired, opening access to Providence, Rhode Island

- Finally, on March 1, 1893 the New Haven leased the very large Old Colony Railroad.

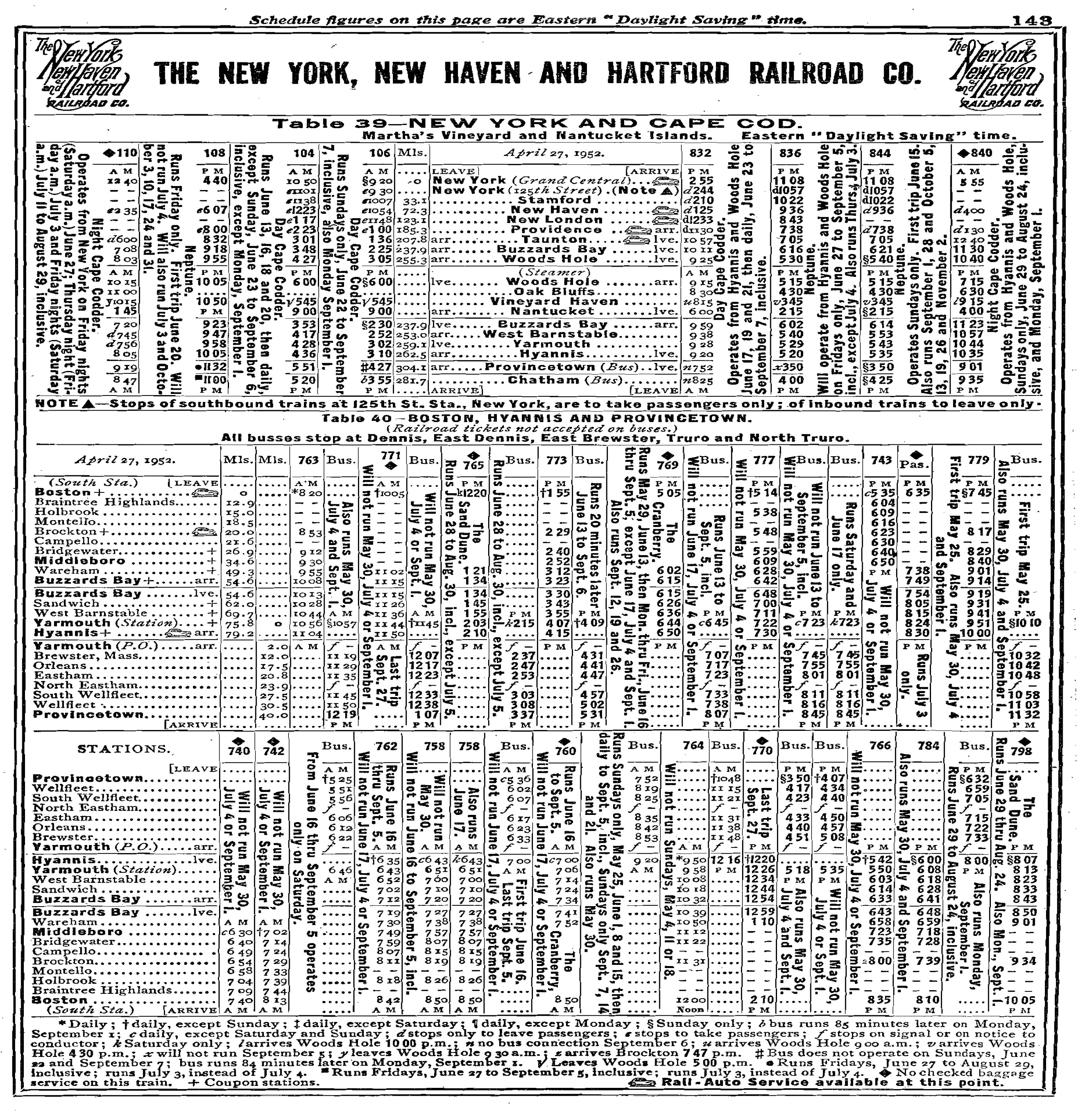

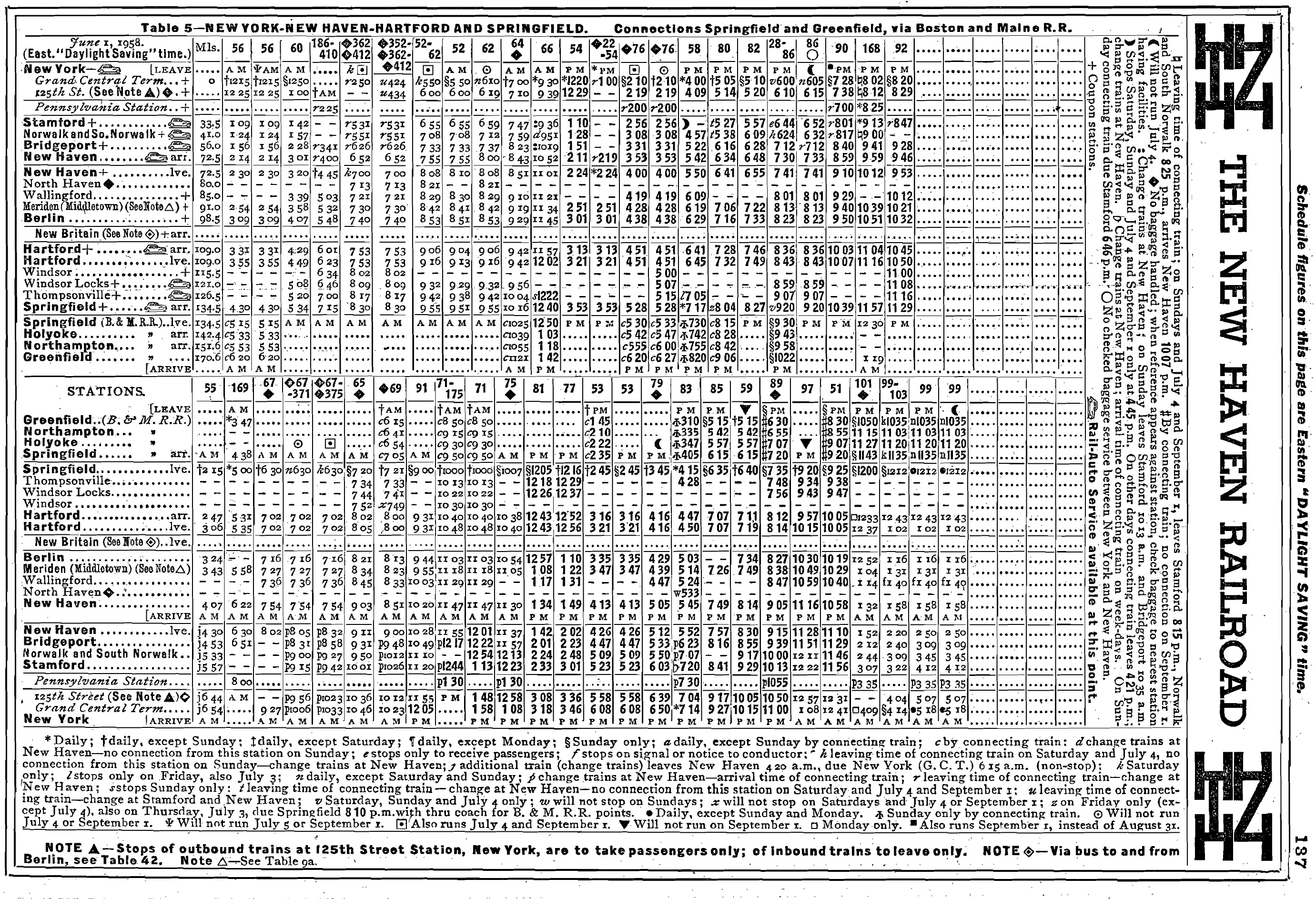

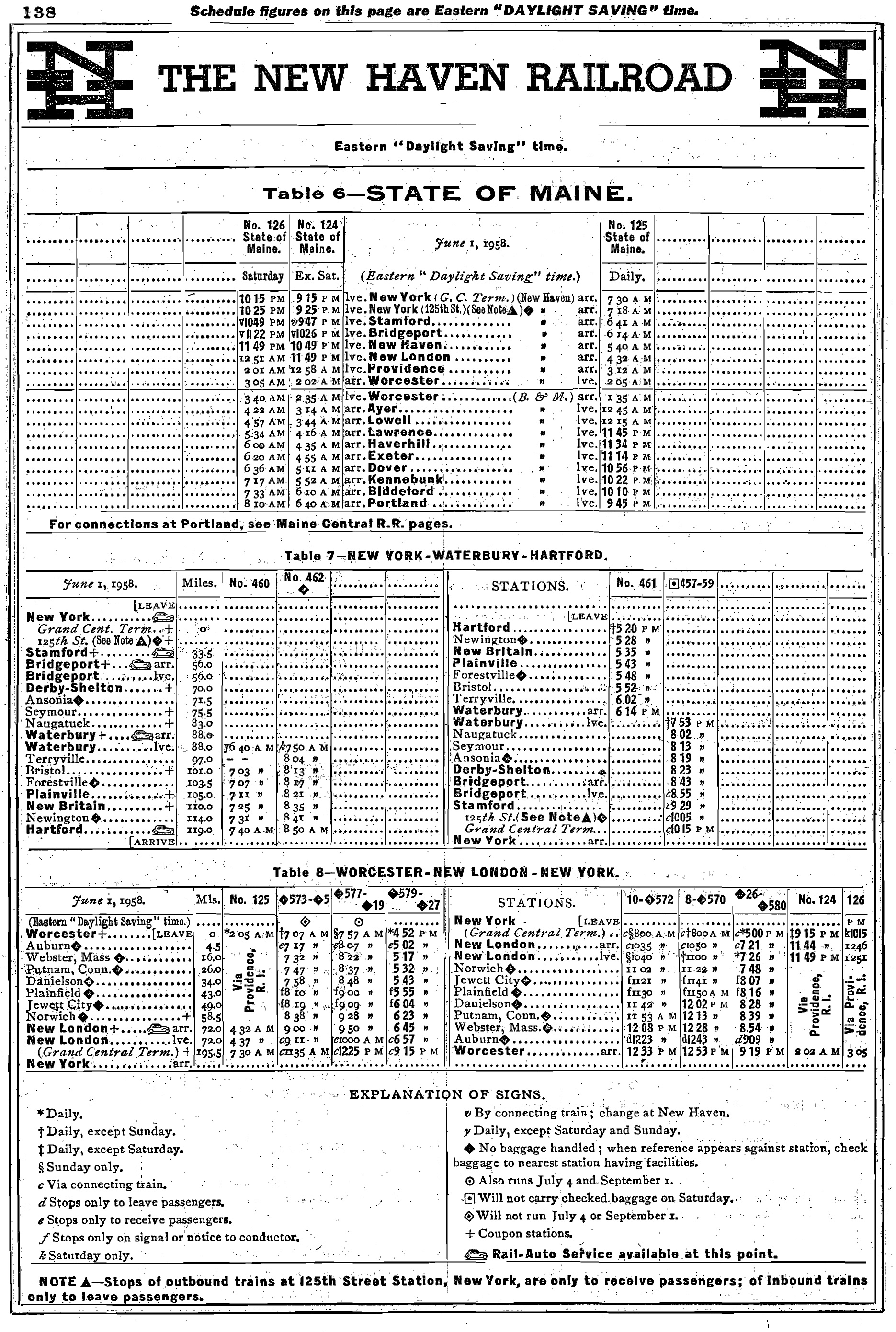

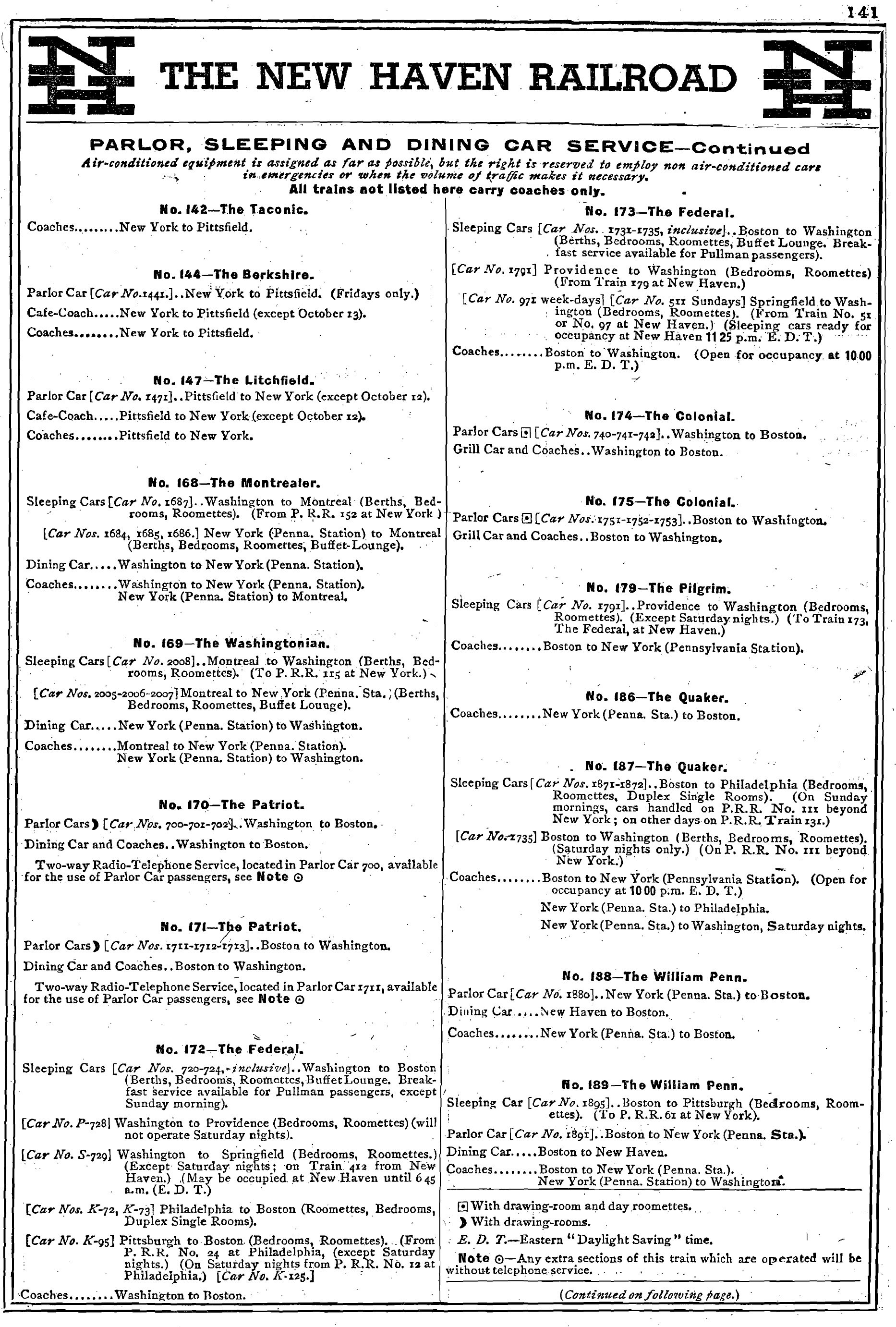

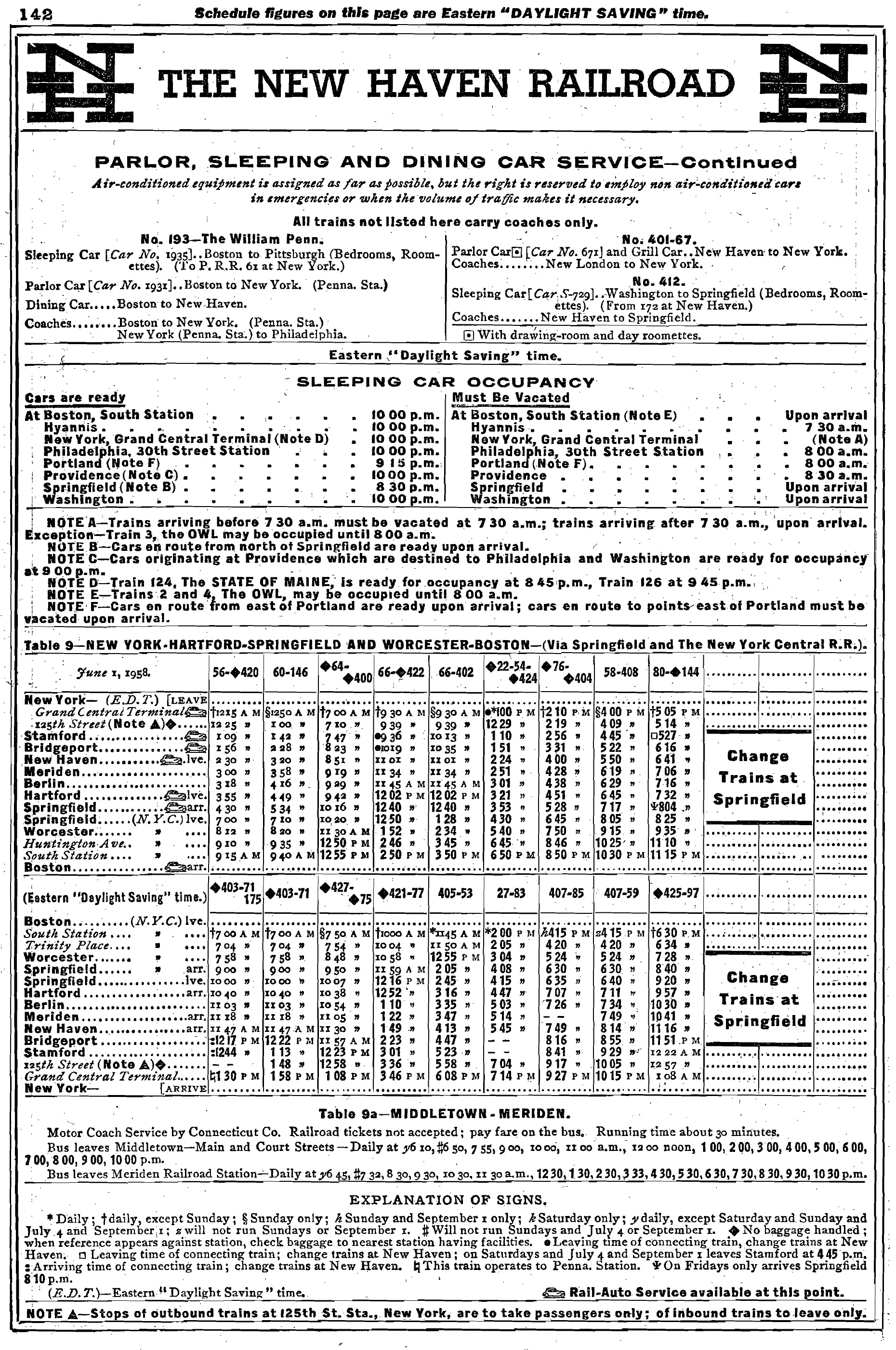

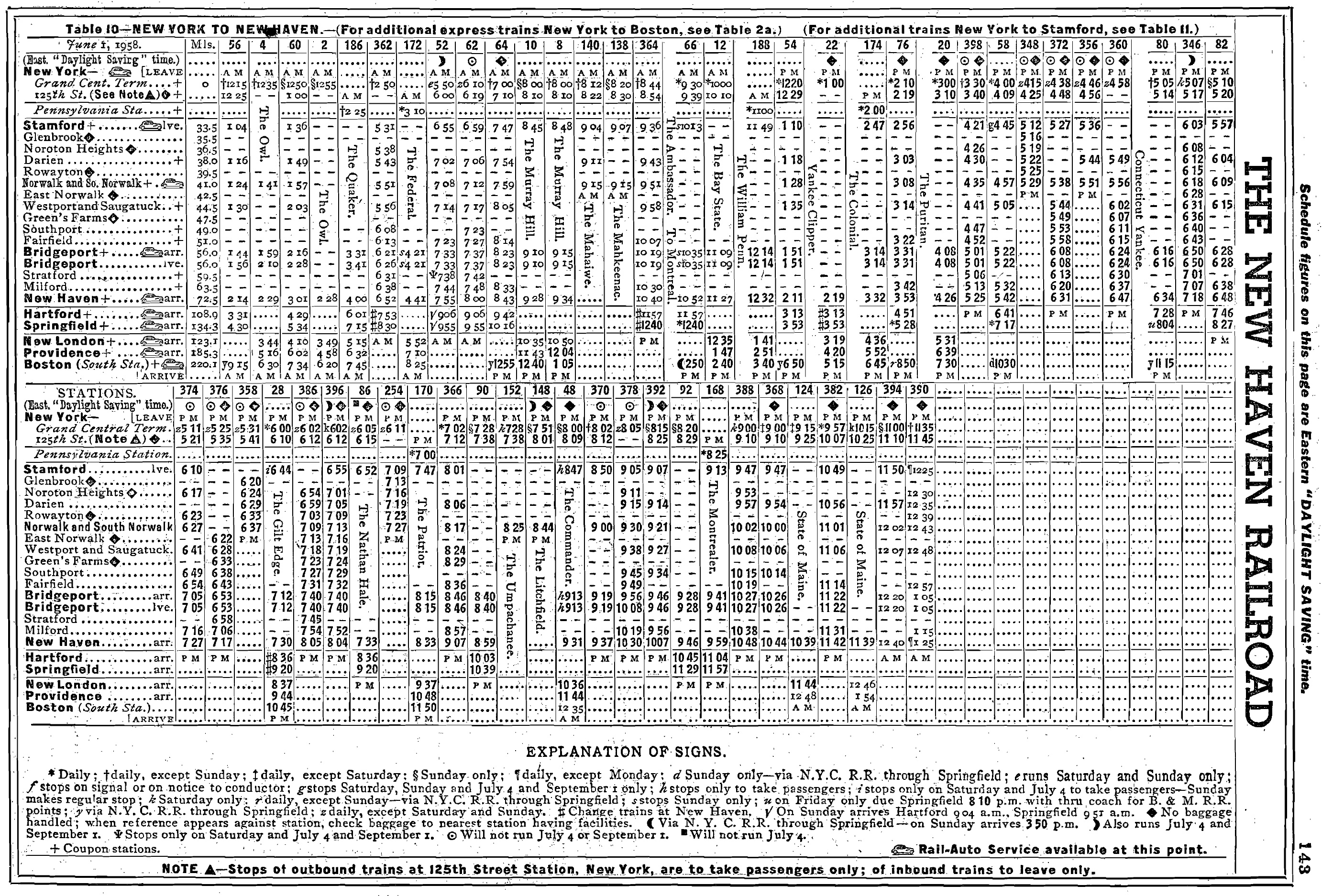

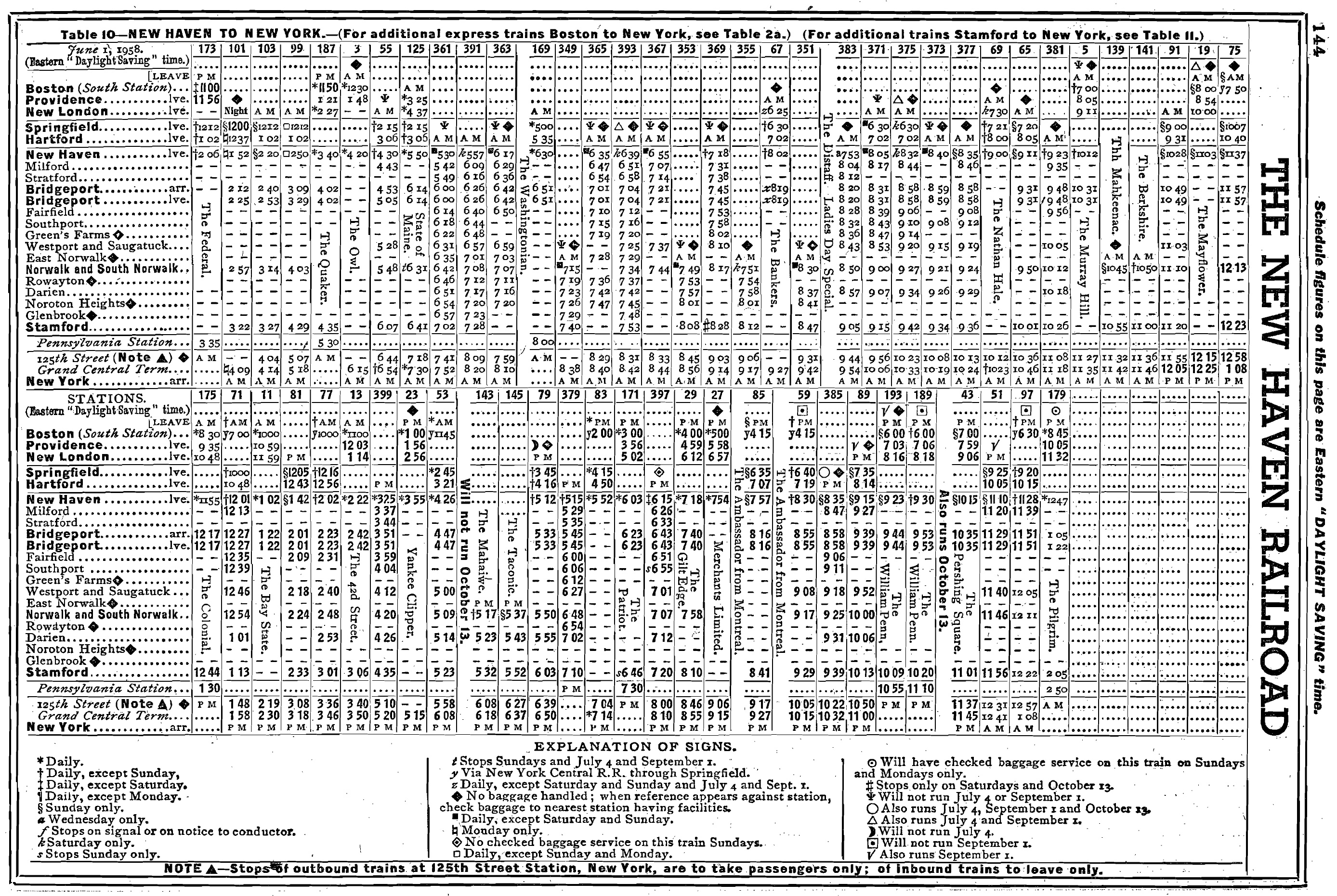

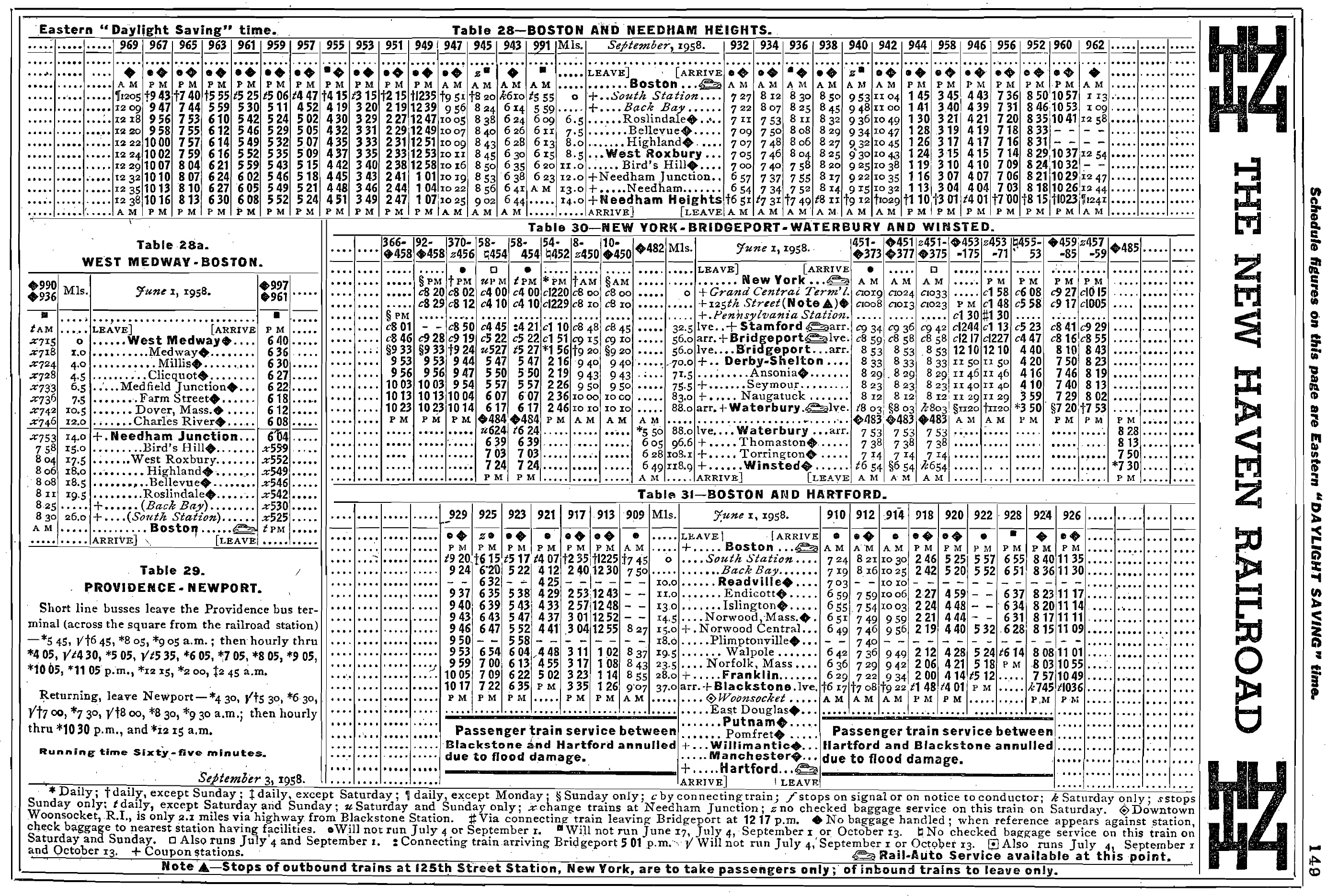

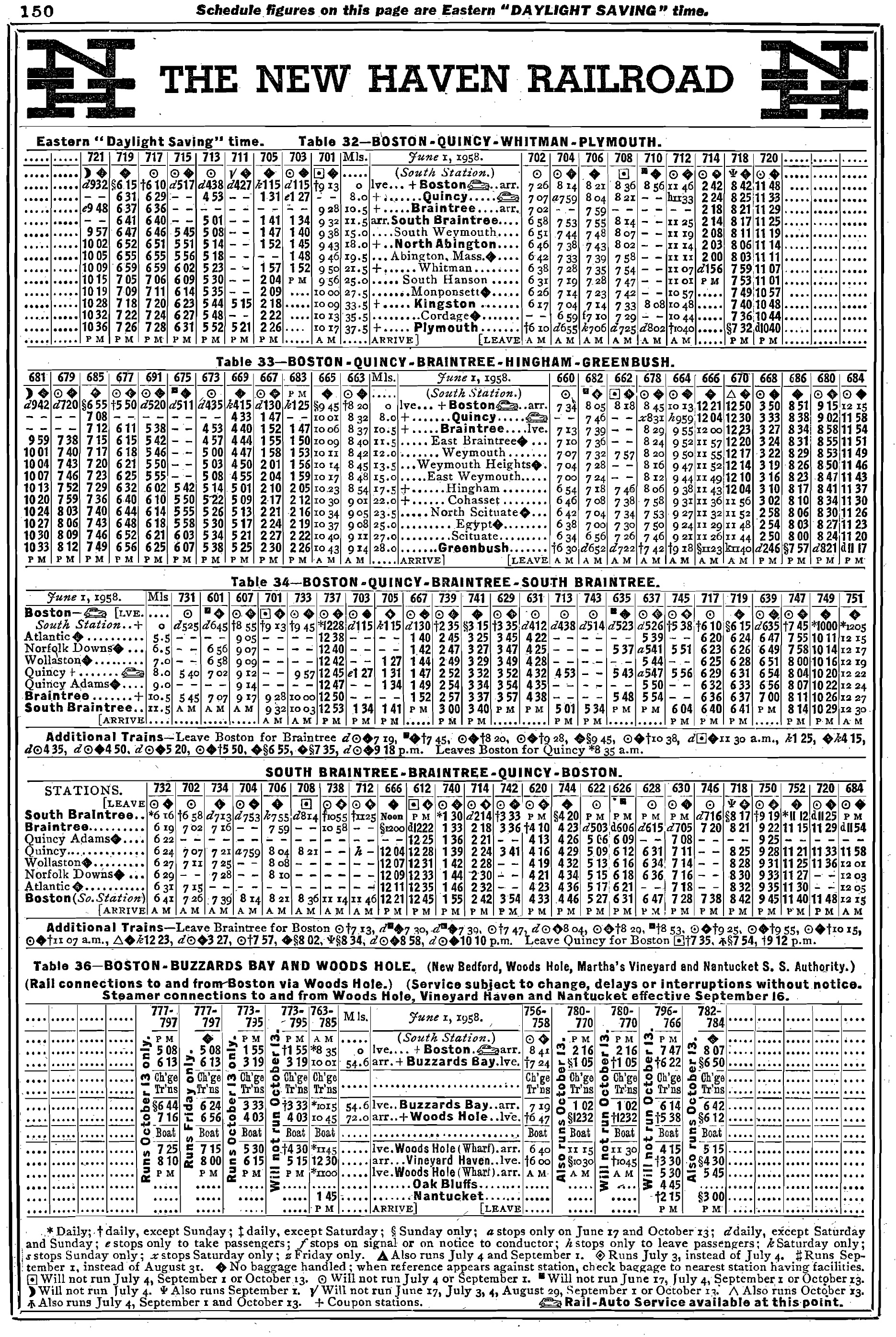

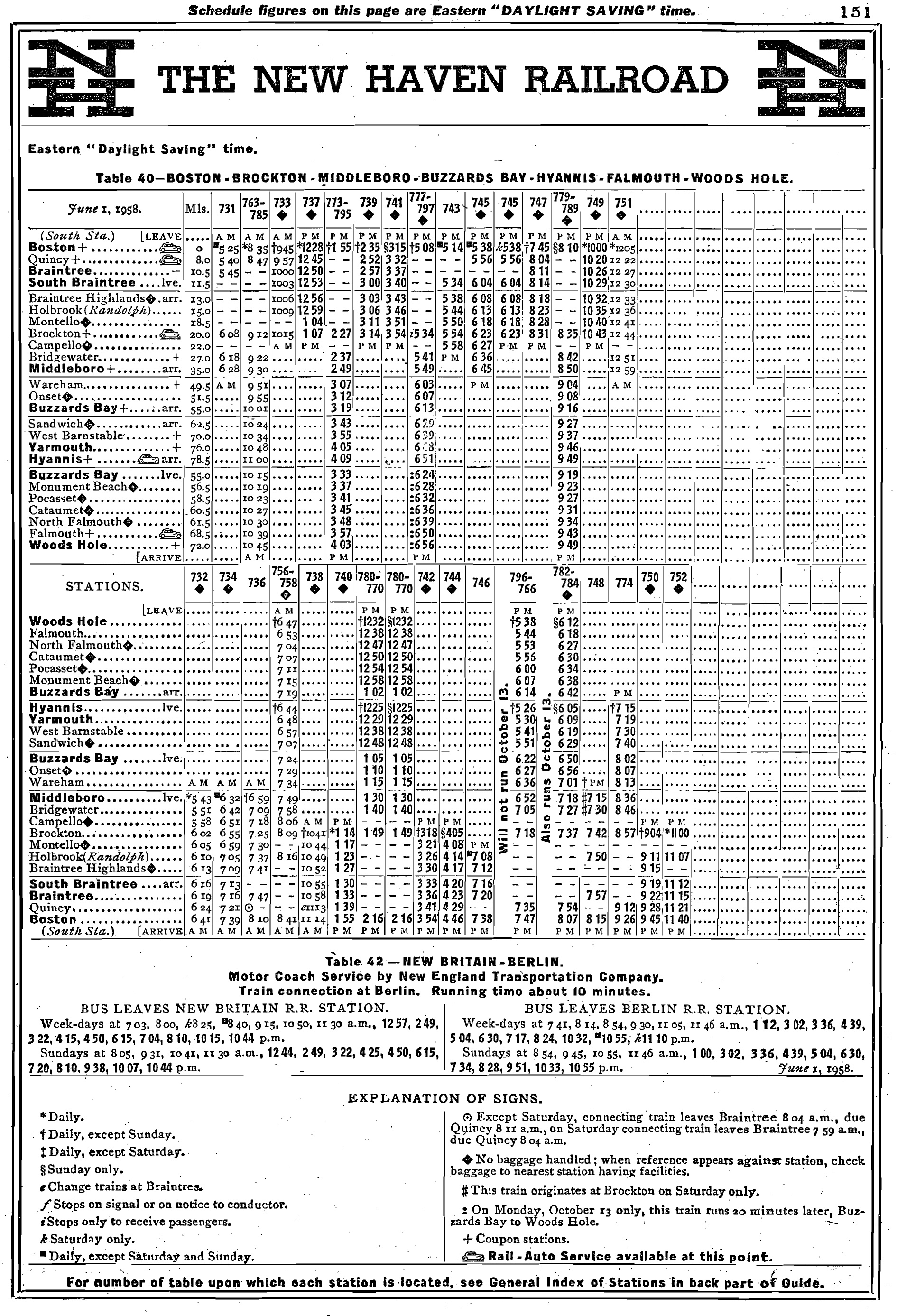

Schedule and Timetables (1952)

The Old Colony comprised the entirety of its eastern network running across southern and eastern Massachusetts from Providence, Rhode Island to Boston, Fitchburg, Lowell, Newport, New Bedford, and Plymouth. It also snaked out across Cape Cod reaching Buzzards Bay, Brewster, Chatham, and Provincetown.

The New Haven added a few additional systems (including leasing the Providence & Worcester, which spun-off as an independent decades later in 1973) but by the turn of the 20th century was largely in place. Its final major acquisition was the 1904 addition of the Central New England Railway.

The CNE had a rugged profile but proved a key route, connecting Springfield and Hartford with Campbell Hall, Poughkeepsie, and Rhinecliff, New York. With the opening of the Poughkeepsie Bridge in early 1889 the line blossomed as a western gateway for handling freight moving to and from the Midwest.

At Campbell Hall/Maybrook, New York there were important interchanges established with the Lehigh & New England; Erie; Lehigh & Hudson River; New York, Ontario & Western; and to a lesser extent the New York Central

New Haven GP9 #1209 has a train made up of Pennsylvania coaches at Forest Hills, Massachusetts during the 1960's. Fred Marder photo. Author's collection.

New Haven GP9 #1209 has a train made up of Pennsylvania coaches at Forest Hills, Massachusetts during the 1960's. Fred Marder photo. Author's collection.The bridge was vital for these smaller roads (except the NYC) as a means to compete against the Central, Pennsylvania, and Baltimore & Ohio in moving traffic from the Midwest to the Northeast/New England.

While freight was important, the New Haven thrived on transporting passengers in an increasingly-populated region. The company was never more powerful than directly at the start of the 20th century. It moved all types of passengers ranging from those traveling long-distance to local commuters.

It also handled a rather robust seasonal business by working with other roads to offer trains like the East Wind (Washington - Bangor, Maine) and Bar Harbor Express (Washington - Ellsworth, Maine) for vacationers.

Early on, the New Haven worked with the New York Central to gain entry into Manhattan and then later reached PRR's new Pennsylvania Station when Hell Gate Bridge (via the New York Connecting Railroad) opened on March 9, 1917.

A company photo showcasing recently delivered New York, New Haven & Hartford PA-1 #0767, circa 1948.

A company photo showcasing recently delivered New York, New Haven & Hartford PA-1 #0767, circa 1948.In its quest to dominate New England it would eventually control the Boston & Maine, Ontario & Western, Maine Central, and Rutland according to Mr. Schafer's book.

Unfortunately, the monopolistic nature of this crusade eventually forced the government's hand and the New Haven was required to divest these holdings due to antitrust lawsuits.

At around the same it was embarking upon electrification, opening 21 miles between Woodlawn, New York and Stamford, Connecticut utilizing an 11,000-volt, AC system.

By World War I it had energized its main line as far east as New Haven, its New Canaan Branch, and along the line to Pittsfield, Massachusetts as far north as Danbury, Connecticut. The results of these projects and its numerous light density branch lines forced the road into bankruptcy in 1935, also brought about by the Great Depression's economic downturn.

Electrified Operations

The New Haven's electrified operations would pioneer the use of alternating current (AC) transmission, today the most commonly used form of power in the industry.

Its energized territory had a very useful and practical purpose despite the immense cost of the project; the New Haven served millions of commuters and long-distance services in conjunction with the Boston & Maine, Pennsylvania, and Maine Central all along the east coast.

New Haven 44-tonner #0815 at the Charles Street Roundhouse in Providence, Rhode Island. Date not recorded. These little critters were well-liked for their ability to switch customers with tight clearances, found throughout New England. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven 44-tonner #0815 at the Charles Street Roundhouse in Providence, Rhode Island. Date not recorded. These little critters were well-liked for their ability to switch customers with tight clearances, found throughout New England. American-Rails.com collection.Today, its New York-Boston main line is integral part of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. The NYNH&H had considered electrifying its railroad as early as the late 19th century when the B&O electrified its Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore during 1895.

The catalyst that eventually spurred it into action was the ability to serve New York Central's new Grand Central Terminal. It also later served PRR's new Pennsylvania Station. After carefully considering various transmissions from AC to DC the New Haven decided upon an 11,000-volt AC system.

New Haven GP9 #1211 and a few FB-2's work freight service eastbound through New London, Connecticut on May 29, 1965. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven GP9 #1211 and a few FB-2's work freight service eastbound through New London, Connecticut on May 29, 1965. American-Rails.com collection.At the time this was a radical decision using an untried and unproven current in main line service; prior to this railroads always utilized DC (direct current). However, AC had key advantages and the New Haven planned to tap into those.

Direct current has fundamental drawbacks such as providing relatively low voltage (usually no higher than 3,000 volts), requiring large amounts of equipment to properly retain power throughout the system (because of the current’s considerable size), and needing power supplies (i.e., substations) at regular intervals to maintain sufficient power.

Instead, alternating current, or AC, has become the favored means of electrification for many systems worldwide since the 1930s. Alternating current has none of the inherent issues of DC systems; it utilizes relatively cheaper overhead wires (catenary) and can be strung for hundreds of miles without losing power.

A pair of New Haven DL-109's with a passenger train that appears to be running the Shore Line during the 1950s. Author's collection.

A pair of New Haven DL-109's with a passenger train that appears to be running the Shore Line during the 1950s. Author's collection.The NYNH&H completed its first stretch of electrified territory between Woodlawn Junction, New York and Stamford, Connecticut in the summer of 1907 while by 1915 wires reached New Haven.

During 1920s the NYNH&H had strung wires over some 672 miles of track, which proved the pinnacle of its electrified territory.

The railroad planned to reach Boston but lack of funds forced its hand in terminating the project at New Haven (Amtrak would finally close "the gap" in the early 2000s).

Initially the New Haven experienced frequent service failures with its AC system, which perhaps is to be expected when developing a brand new, untried technology.

However, within a few years it had fixed most of the kinks and outage problems. In the succeeding years the road operated a wide variety of electric locomotives, most New delivered from Westinghouse.

Its first batch of 41 featured a B-B wheel arrangement with gearless traction motors (although over-the-road issues forced the motors to be rebuilt with added, un-powered, front “pony” trucks).

They were classified as EP-1s and rated at around 1,000 horsepower, used exclusively in passenger service (thus their EP designation which stood for "Electric Passenger").

In a scene likely dating to 1969, former New Haven U25B's layover at Maybrook, New York during the early Penn Central era. Richard Wallin photo. Author's collection.

In a scene likely dating to 1969, former New Haven U25B's layover at Maybrook, New York during the early Penn Central era. Richard Wallin photo. Author's collection.The freight variant of the EP-1 was the EF-1; sporting a 1-B-B-1 wheel arrangement the NYNH&H took delivery of 36 examples.

They carried geared traction motors with side-rods and utilized north of New York City where they did not have to be equipped for both overhead and third-rail running like their EP-1 cousins (New York Central’s electrified lines were entirely third-rail powered).

Around 1920 the NYNH&H took delivery of its "second-generation" motors. These were classified as EP-2s and they carried a 1-C-1+1-C-1 wheel arrangement, producing roughly double the power of their earlier counterparts. Although more powerful than the EP-1s, they were essentially of the same design and build.

New Haven's electrics would pave the way for future models that were not only more powerful and efficient but also for the first time included good looks and streamlining, such as was the case with the double-ended EF-3 and and EP-4.

The last passenger variant was the EP-5, 1955 products of General Electric. The very last electrics New Haven acquired were the twelve former EL-C's of the Virginian Railway, also built by GE in 1955. The units were sold by successor Norfolk & Western in 1962 whereupon the New Haven reclassified them as EF-4.

Through World War II the NYNH&H did well under the guidance of Howard Palmer, who abolished many unprofitable ventures (such as its steamship and bus services), streamlined operations, and quickly replaced remaining steam power with new diesels and electrics.

In an ironic turn of events, it emerged from receivership in 1948 only to be taken over that same year by Frederic Dumaine and Patrick McGinnis. These two individuals, particularly the latter, helped expedite the company's fate over the next decade.

New Haven FA-1's #0401 and #0418 appear to be tied down in New Haven, Connecticut; August 6, 1965. G. Berisso photo. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven FA-1's #0401 and #0418 appear to be tied down in New Haven, Connecticut; August 6, 1965. G. Berisso photo. American-Rails.com collection.Under their "pencil pusher" leadership the duo slashed costs wherever possible (taking this to extremes whereby it did more harm than good), cut down the work force by laying off even the most veteran workers, and began deferring maintenance to save money.

Such tactics typically only work for a short time and it was not long before these endeavors affected the railroad in a negative way.

Dumaine's son acquired his father's stakes following the elder's passing in 1951 but he quickly ran afoul of McGinnis who was able to acquire direct control in 1954. In 1956 the railroad's directors had had enough and replaced the latter with George Alpert.

New Haven DL-109 #0722 departs Boston's South Station with "The Cranberry" (Boston - Hyannis, Massachusetts) during the early 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven DL-109 #0722 departs Boston's South Station with "The Cranberry" (Boston - Hyannis, Massachusetts) during the early 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.Penn Central

Unfortunately, the failed ideas of the previous leadership, a dying freight and passenger market, too many light density branch lines, and a Northeast rail network too heavily saturated, Alpert had little success in turning around the railroad's fortune.

All of these factors resulted in a destitute company and it declared bankruptcy in 1961. With a bleak future the railroad felt merger was the only option and pushed for inclusion into the new Penn Central Transportation Company.

The Interstate Commerce Commission sided with this idea despite protests from the New York Central and Pennsylvania's management during merger proceedings.

When such unions are being planned, few companies ever want straddled with a money-losing operation but unfortunately the PC had no choice

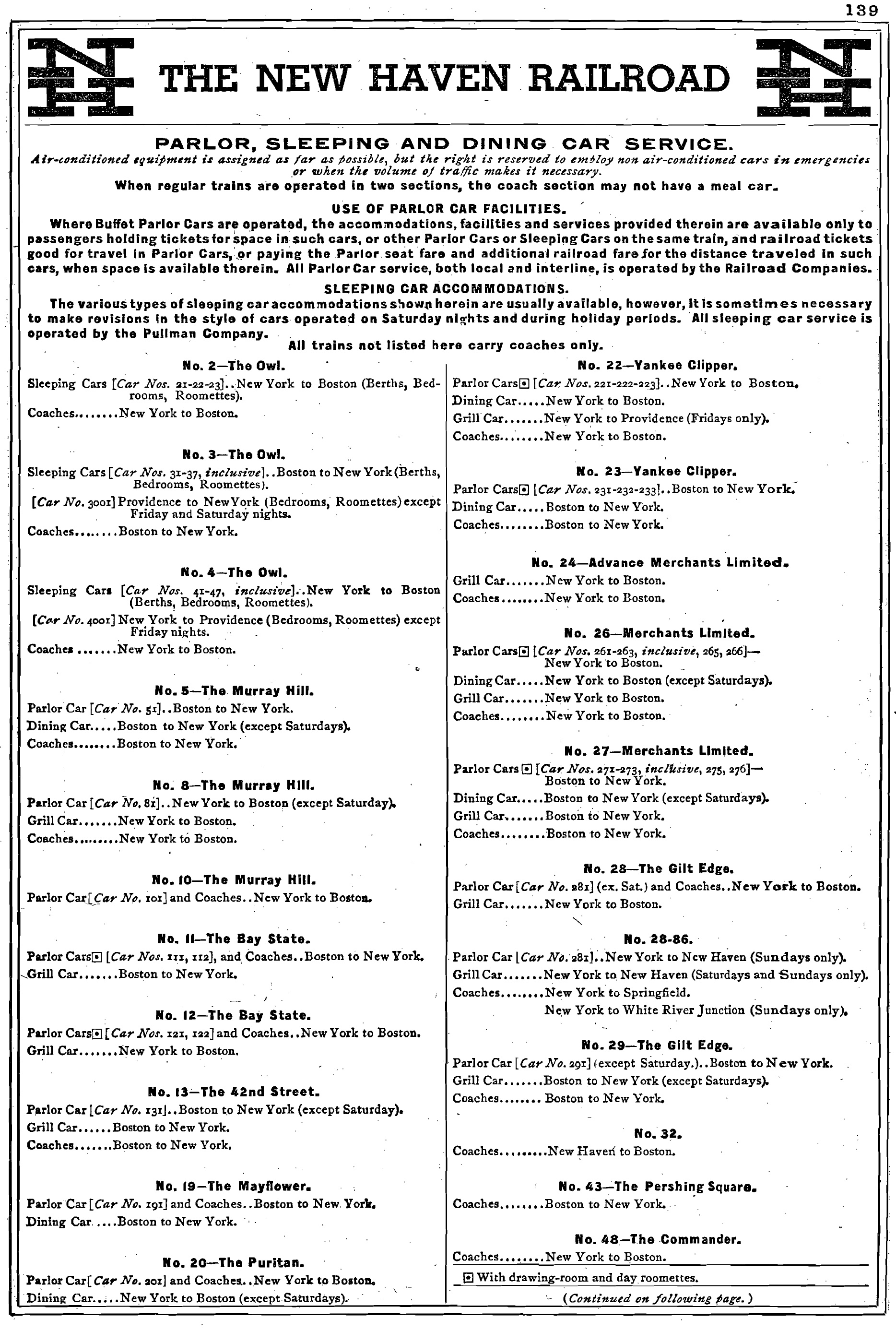

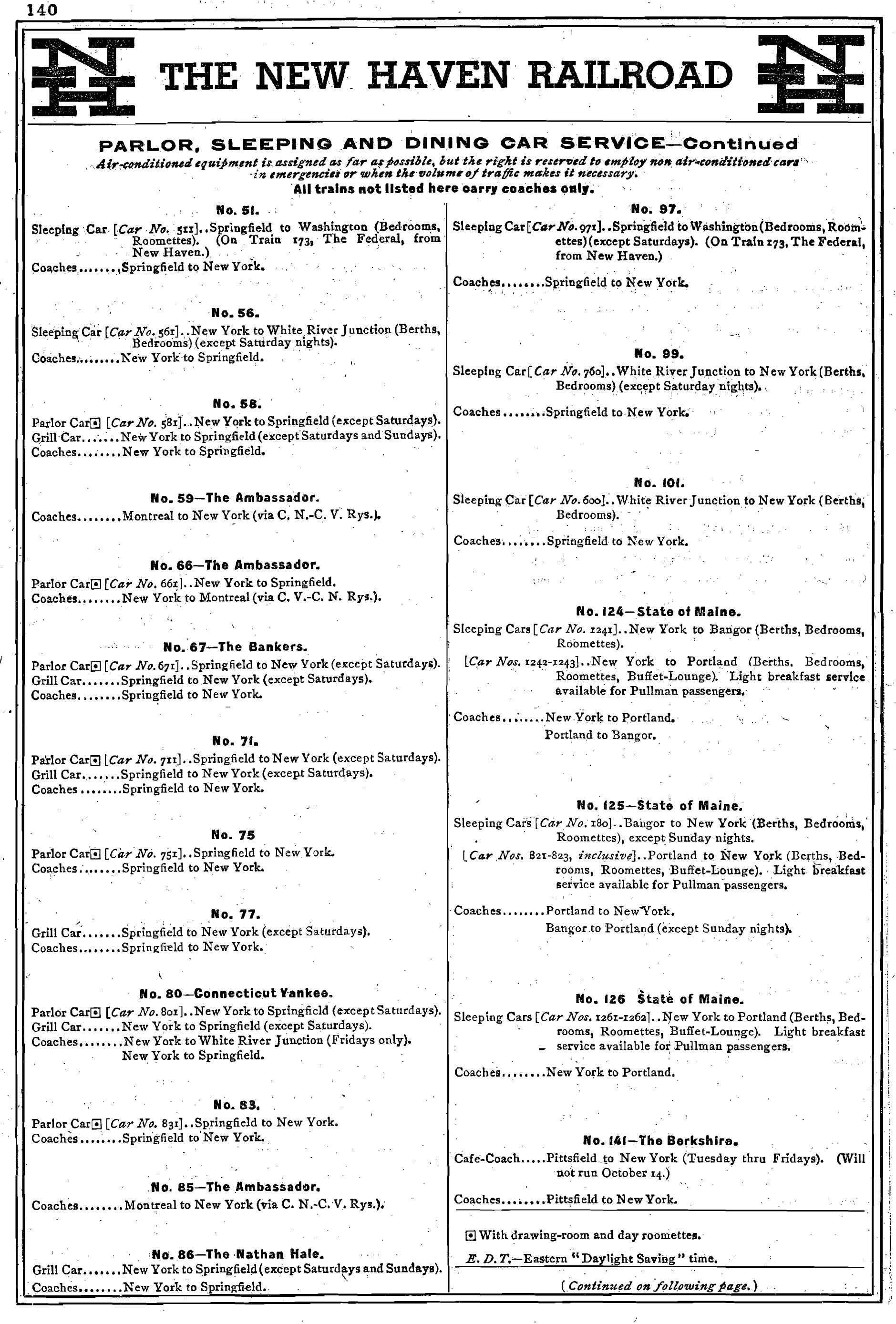

Passenger Trains

Bankers: (New York - Springfield)

Bar Harbor Express: (Washington - Ellsworth, Maine)

Bay State: (New York - Boston)

Berkshires: (New York - Pittsfield)

Bostonian: (New York - Boston)

Colonial: (New York - Philadelphia)

Commander: (New York - Boston)

Day Cape Codder: (New York - Hyannis/Woods Hole)

Day White Mountains: (New York - Berlin, New Hampshire)

East Wind: (Washington - Bangor, Maine)

Federal: (New York - Philadelphia)

Forty-Second Street: (New York - Boston)

Gilt Edge: (New York - Boston)

Hell Gate Express: (New York - Boston)

Merchants Limited: (New York - Boston)

Montrealer/Washingtonian: (Washington - New York - Montreal)

Murray Hill: (New York - Boston)

Narragansett: (New York - Boston)

Nathan Hale: (New York - Springfield)

Naugatuck: (New York - Winsted)

New Yorker: (New York - Boston)

Night Cap: (New York - Stamford, Connecticut)

Owl: (New York - Boston)

Patriot: (New York - Philadelphia)

Pilgrim: (New York - Philadelphia)

Puritan: (New York - Boston)

Quaker: (New York - Philadelphia)

Roger Williams: (New York - Boston)

Senator: (New York - Philadelphia)

Shoreliner: (New York - Boston)

State of Maine: (New York - Portland, Maine)

William Penn: (New York - Philadelphia)

Yankee Clipper: (New York - Boston)

A new PA-1 #0773, draped in the company's handsome Pullman Green livery with Dulux Gold pinstriping, circa 1949. The New England carrier was a loyal Alco customer but never followed up for the later PA-2.

A new PA-1 #0773, draped in the company's handsome Pullman Green livery with Dulux Gold pinstriping, circa 1949. The New England carrier was a loyal Alco customer but never followed up for the later PA-2.On merger day pandemonium ensued and the new railroad fell apart right from the start. As the crisis worsened, PC was burning through nearly $1 million a day and trains were lost throughout the system.

Ironically, amid the chaos New Haven joined the Penn Central on January 1, 1969. After only two years and with financial assistance completely gone, an impoverished Penn Central officially declared bankruptcy on June 21, 1970.

It became so bad that the railroad was facing total shutdown if financial assistance, any means of help at all, were not located.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA-1 | 0400-0429 | 1947 | 30 |

| FB-1 | 0450-0464 | 1947 | 15 |

| S2 | 0600-0621 | 1944 | 22 |

| RS1 | 0660-0671 | 1948 | 12 |

| DL-109 | 0700-0759 | 1942-1945 | 60 |

| HH-600 | 0911-0920 | 1937-1938 | 10 |

| HH-660 | 0921-0930 | 1940 | 10 |

| FB-2 | 465-469 | 1951 | 5 |

| RS2 | 500-516 | 1947-1948 | 17 |

| RS3 | 517-561 | 1950-1952 | 45 |

| PA-1 | 760-786 | 1948-1949 | 27 |

| S1 | 931-995 | 1941-1949 | 65 |

| RS11 | 1400-1414 | 1956 | 15 |

| C425 | 2550-2559 | 1964-1965 | 10 |

Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| LS-1200 | 630-639 | 1950 | 10 |

| RP-210 | 3000-3001 | 1956 | 2 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW1200 | 640-659 | 1956 | 20 |

| GP9 | 1200-1229 | 1956 | 30 |

| FL9 | 2000-2059 | 1957-1960 | 60 |

Fairbanks-Morse

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H16-44 | 560-569, 1600-1614 | 1950, 1956 | 25 |

| CPA24-5 (C-Liner) | 790-799 | 1951-1952 | 10 |

| P12-42 | 3100-3101 | 1957 | 2 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 0800-0818 | 1941, 1945 | 19 |

| U25B | 2500-2525 | 1964-1965 | 26 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A-1 Through A-3 (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| B-1 Through B-4 (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| C-1a Through C-22 (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| D-1 Through D-17 (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| E-1 Through E-15 | American | 4-4-0 |

| F-1 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| F-3, F-5, P-1 Through P-5 (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| G-1 Through G-4 (Various) | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| H-1 Through H-4 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| I-1 Through I-4/e/f | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| I-5 | Hudson | 4-6-4 |

| J-1, J-2 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| K-1 Through K-5 (Various), M-1 Through M-8, N-1 Through N-3-a/b | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| L-1-a | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| O-1 | Saddle Tank | 0-4-6T |

| R-1 Through R-3 (Various) | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| S-1 Through S-8 | Saddle Tank | 0-4-6T, 0-4-4T, 2-4-4T |

| T-1 Through T-4 | Switcher | 0-6-0/T |

| U-1 Through U-5 (Various) | Switcher | 0-6-0/T |

| V-1 Through V-5 | Switcher | 0-6-0/T |

| Y-1 Through Y-8 | Switcher | 0-4-0/T, 0-8-0 |

| Z-1, Z-2 | Saddle Tank | 2-4-6T, 2-4-4T |

New Haven FA-1's and FB-1's, led by #0421, power a freight west/south through New Haven, Connecticut on September 11, 1957. David Sweetland photo. American-Rails.com collection.

New Haven FA-1's and FB-1's, led by #0421, power a freight west/south through New Haven, Connecticut on September 11, 1957. David Sweetland photo. American-Rails.com collection.Conrail

Realizing the severity of the situation the federal government stepped and setup the Consolidated Rail Corporation, which comprised the skeletons of several bankrupt Northeastern carriers. It officially launched on April 1, 1976.

With federal backing Conrail began to slowly pull out of the red ink and by the late 1980s was a profitable railroad after thousands of miles of access trackage was abandoned and/or upgraded.

The New Haven's secondary lines comprised a portion of these abandonments, as large sections were let go and considered superfluous for a railroad trying to recover.

However, the New York - Boston main line continues to be an important link for both freight and passengers, especially Amtrak where the line is part of the carrier’s Northeast Corridor.

In addition, other key routes remain in use for commuter and freight operations. On an even brighter note the old “McGinnis” livery has reemerged under the Connecticut Department of Transportation for its local commuter services.

A New Haven shop train, led by C425 #2550 and a pair of U25Bs, is westbound at New London, CT in April, 1967. Photographer not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.

A New Haven shop train, led by C425 #2550 and a pair of U25Bs, is westbound at New London, CT in April, 1967. Photographer not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.Timetables (October, 1958)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Washington's Whiskey Train Rides

Jul 10, 25 03:06 PM

Climb aboard the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad for a whiskey tasting adventure by train! -

Maryland's Whiskey Train Rides

Jul 10, 25 01:05 PM

You can enjoy whiskey tasting by train at just one location in Maryland, the popular Western Maryland Scenic Railroad based in Cumberland. -

Connecticut's Whiskey Train Rides

Jul 10, 25 11:03 AM

In this article, we'll take a closer look at these special train rides, explore the magic behind them, and offer tips for anyone looking to embark on this memorable journey.