- Home ›

- Fallen Flags ›

- Monon

Monon Railroad: Map, Photos, History, Logo

Last revised: October 13, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway, better known as the "Monon Route," was a local Indiana system serving its home state.

According to Mike Schafer's book, "Classic American Railroads, Volume III" it reached a peak size of 573 miles during the early 20th century.

What began as the New Albany & Salem was initially conceived only to complement waterborne transportation between the Ohio River and Lake Michigan.

This concept ultimately failed as the iron horse proved superior to all other modes of interstate transportation.

History

After operating a linear, north-south route for nearly 30 years a merger during the early 1880's opened new markets to Indianapolis and Chicago. A decade later promoters attempted to access eastern Kentucky's rich coalfields but alas a coup foiled the plan.

Had this been accomplished the railroad would likely have carried a far different, and much more profitable, future than the one in which it played the role of inconsequential regional dependent upon interchange traffic.

Much of this came from its Louisville & Nashville connection at Louisville, the powerful southern Class I which went on to acquire the Monon in 1971.

Today, large sections of the railroad have either been abandoned or sold to short lines. However, some corridors remain in use under successor CSX Transportation.

Photos

Early Heritage

If you are interested in a concise history of the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway I would highly recommend George Hilton's book, "Monon Route." He thoroughly covers its corporate heritage within a condensed title of only a few hundred pages.

While the Monon never grew into a preeminent Midwestern trunk line its history can be traced to the industry's very early days; it was the idea of James Brooks, a man convinced that efficient and high-speed transportation lay in steamboats, not railroads.

He was a prominent businessman of New Albany, Indiana, a small community situated along the Ohio River's western shore and directly across from Louisville, Kentucky. Despite his belief, Brooks still felt the railroad could aid watercraft by operating as part of an intermodal network.

New Albany & Salem Rail Road

This led to the New Albany & Salem Rail Road's (NA&S) organization in the spring of 1847 (made official by Indiana Governor James Whitcomb on July 31st as a recognized corporation) to connect New Albany with Salem.

Its creation was also thanks, in part, to the state which passed an act earlier that year on January 25th stipulating a railroad should be constructed between those points in place of a wagon road.

As an additional incentive, Indiana later authorized it could build anywhere within the state, as long as the initial segment was finished. Brooks quickly jumped on this incredible opportunity, realizing it would enable him to carry out his waterway-railroad concept.

By the summer of 1848 initial funding was in place and after just three years of work the line to Salem was completed on January 14, 1851. Now free to build wherever he chose, Brooks embarked upon a northerly route to the lakefront at Michigan City where a port terminal would be established.

Logo

Unfortunately, the entire project was riddled with mistakes right from the start. Its most pressing issue was a substandard right-of-way carrying steep grades and sharp curves.

The engineers hired were simply unsuitable for the job, so poor in fact they decided to use that same wagon road as a guide in surveying the lineout of New Albany!

The grades along this segment were as steep as 1.53% and were an operational headache throughout the steam era.

The line reached Bedford on April 18, 1853 but wound up with four blocks of street running as a condition of serving that point. It became one of four such locations where the modern Monon was stuck on the streets.

Brooks even erred at the southern terminus, New Albany; he strangely constructed the railroad's facilities some six blocks away from the Ohio River waterfront, which meant freight and passengers traveling via steamboat had to be transported this distance to and from the NA&S depot.

When the Monon later utilized the huge Kentucky & Indiana Bridge here in reaching Louisville, the railroad was again forced onto the streets (15th Street), a setup that survives to this day. As the project pushed north, Bloomington was reached on October 11, 1853.

The next blunder was a failure to complete a branch started from Gosport to Indianapolis (this grade was later purchased, and completed, by a Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary), which would have provided a more direct line to the state capital rather than what wound up being a southeastern branch from Monon, Indiana.

In a final bizarre move, officials decided that to save construction costs the first 45 miles to Campbellsburg (just north of Salem) would be laid with strap-iron rail; even for this period such technology was growing increasingly outdated with the development of modern, and much safer, T-rail. After several accidents and service disruptions, the strap-iron was fully replaced by April of 1857.

Monon C420's lead a southbound freight at the north end of New Albany, Indiana along Monon Avenue on June 26, 1971. American-Rails.com collection.

Monon C420's lead a southbound freight at the north end of New Albany, Indiana along Monon Avenue on June 26, 1971. American-Rails.com collection.For Brooks' shortcomings he unquestionably recognized the potential in his company's charter. While the southern section was under construction he secured financing through the Michigan Central for the northern component.

This subsidiary of the New York Central provided $500,000 in capital in exchange for NA&S's rights to build across northern Indiana and provide it a coveted Chicago connection. As part of the agreement, NA&S would also gain trackage rights into the Windy City.

The new line south of Michigan City (built to higher standards with relatively gentle grades) was completed and opened to Lafayette on October 3, 1853. Beyond this point the NA&S acquired a small short line on June 17, 1852, the Crawfordsville & Wabash (C&W), which extended service as far as Crawfordsville.

To procure a connection with the C&W, here again the NA&S elected to utilize street-running operations along Lafayette's 5th Street. (If one had not studied Monon's history in detail they would probably have assumed the railroad carried an interurban heritage given its extensive street-running operations.) Finally, the NA&S was finished to Gosport on June 30, 1854, completing Brooks' dream of a river-lake corridor.

As Dr. Hilton notes, the difference in the railroad's profile could be witnessed from atop the grade at a location known as the "Tree of Hope," three miles south of Bainbridge. If one were to gaze southward from this point they could easily decipher the railroad's undulating, rugged profile while the northward view would have shown a relatively unencumbered grade.

The gigantic sycamore here was also a point where engineers, working northbound runs, realized the worst of their journey was over. Alas, with insufficient business and heavy debt, Brooks' water-rail concept died as the New Albany & Salem slipped into receivership on October 1, 1858 (this ended his involvement with the company).

Louisville, New Albany & Chicago Railroad

It was subsequently reorganized as the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago Railroad (LNA&C) on October 24, 1859.

New ownership took a more practical (and profitable) approach of integrating the railroad into the national network. They set their sights on the growing city of Louisville as well as opening a route into Chicago (bankruptcy had forfeited the Michigan Central trackage rights).

Despite these promising opportunities, nothing occurred due to stagnate leadership (a handicap the railroad would endure time and again). It made no solid plans to reach Chicago and missed a chance as an early entrant into the southwestern Indiana coalfields.

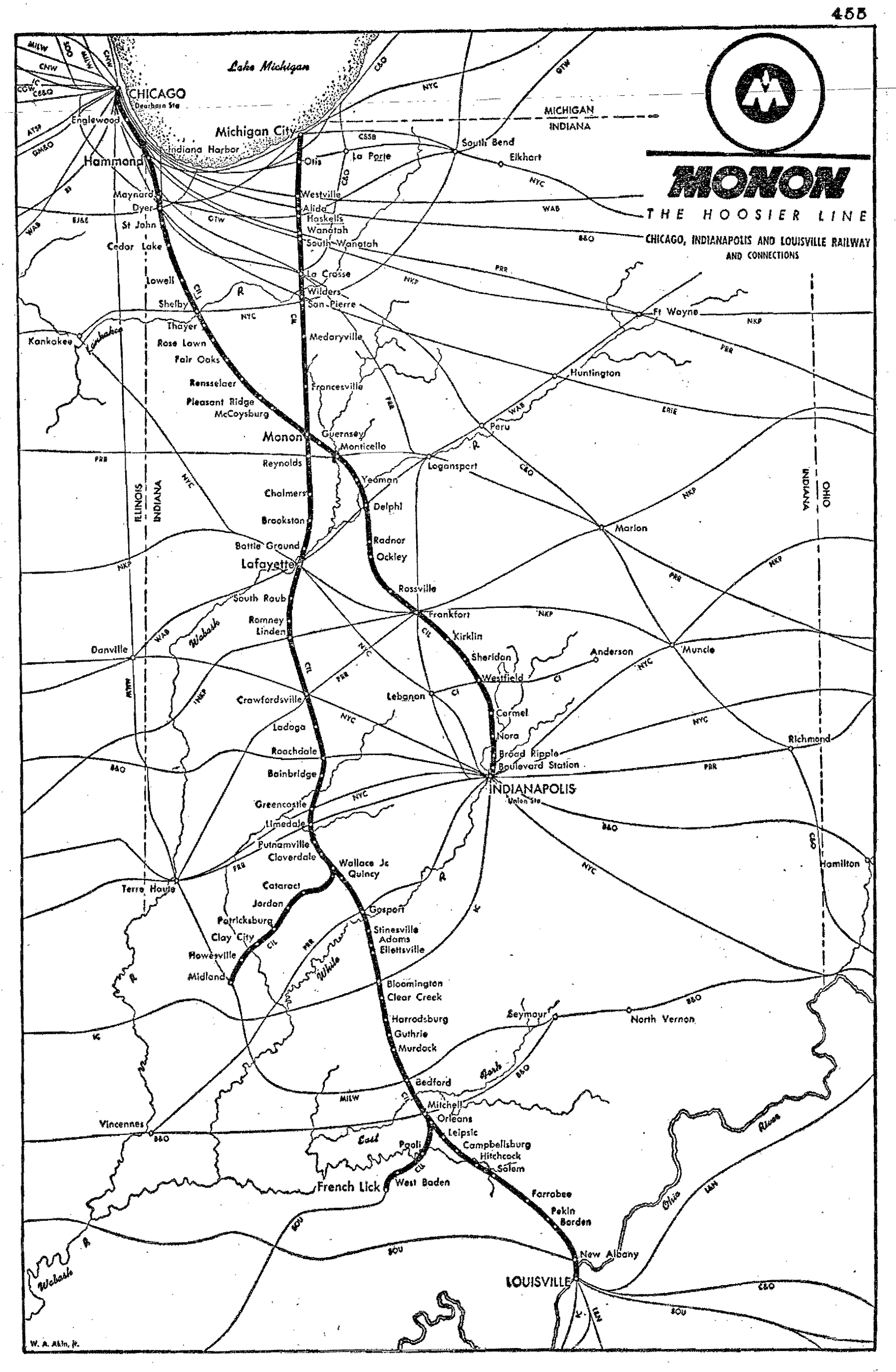

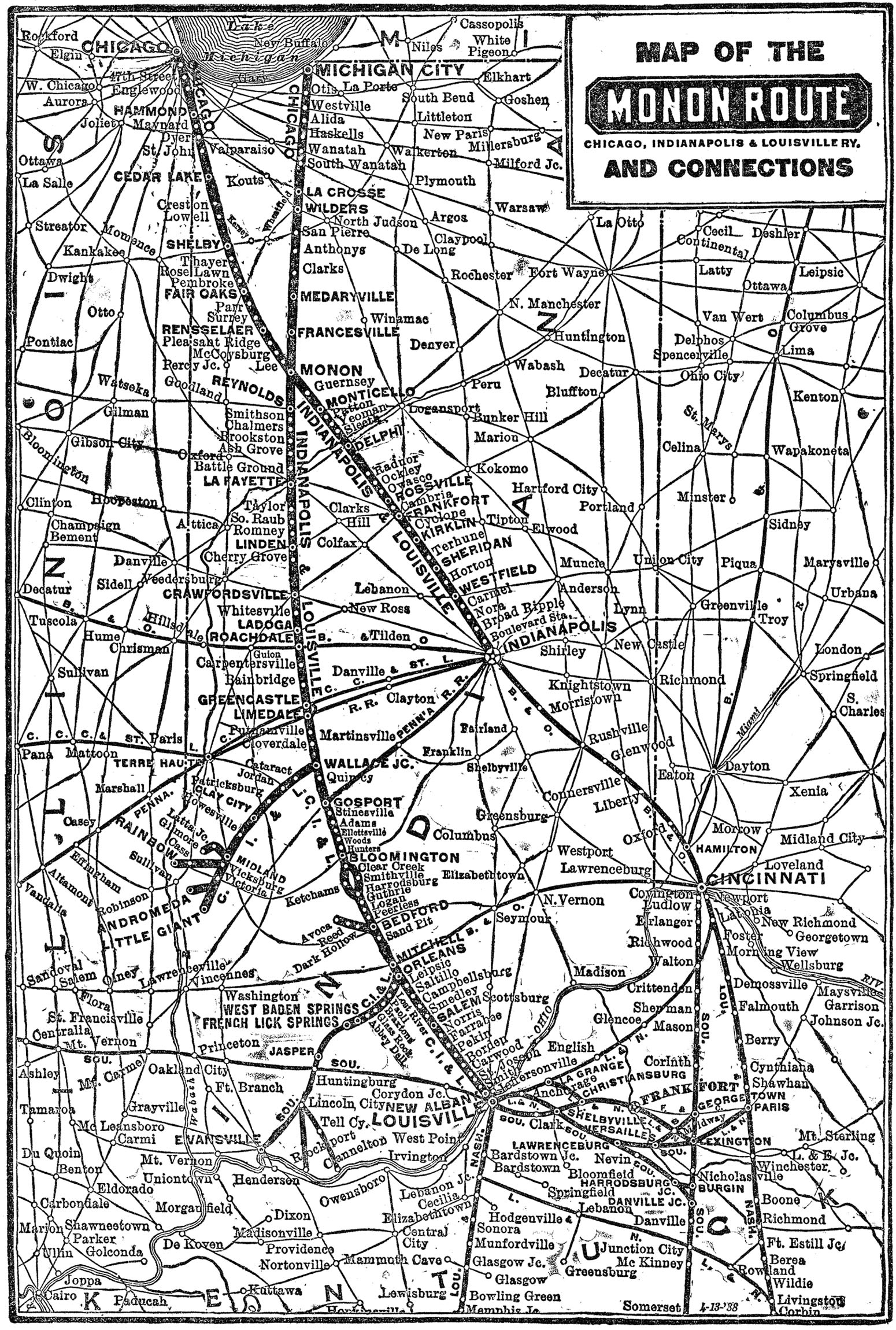

System Map (1938)

An official, 1938 system map of the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville (Monon). Author's collection.

An official, 1938 system map of the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville (Monon). Author's collection.Expansion

After the Civil War two more bankruptcies occurred, first in early 1869 and then again in early 1871. What emerged on January 9, 1873 was a carrier with a similar name, the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago Railway, with essentially the same network.

There was little further development until December 15, 1881 when the LNA&C acquired control of the Chicago & Indianapolis Air Line Railway (C&IAL) in exchange for the former helping finance the latter's line between Rensselaer and Bradford.

- The town's name was later changed to Monon in 1879, the center of the railroad's X-shaped network. The word is said to have originated with the region's Native American peoples, the Potawatomi, and meant "to carry" or "swift running." -

Reaching Chicago

The C&IAL was working on a through route from Indianapolis to Chicago, a project that began in stages over several years starting with the incorporation of the Indianapolis, Delphi & Chicago Railway on June 28, 1865 (later renamed as the C&IAL).

The railroad fully opened in October of 1882 while through passenger service commenced the following spring. Prior to this occurring, it gained partial ownership in the Chicago & Western Indiana as well as C&WI subsidiary, Belt Railway of Chicago. Both proved vitally important as the former offered a major terminal at Dearborn Station and the latter blossomed into a profitable Chicago belt line.

Lincoln Funeral Train

One of the most noteworthy events in railroad history was the transportation of President Abraham Lincoln's body from Washington, D.C. to his hometown of Springfield, Illinois for burial.

The western leg of the Funeral Train's route utilized none other than the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago from Lafayette to Michigan City during the early morning hours of May 1, 1865.

The 1,654-mile journey passed through 180 cities and seven states as it wound its way north from Washington, passed through New York, Albany, and Buffalo before turning southwesterly to Columbus, Ohio.

From this point the train entered Indianapolis then arrived on the LNA&C. Tens of thousands viewed the train and President Lincoln's body during its journey home while it is estimated that some 25 million Americans attended memorial services.

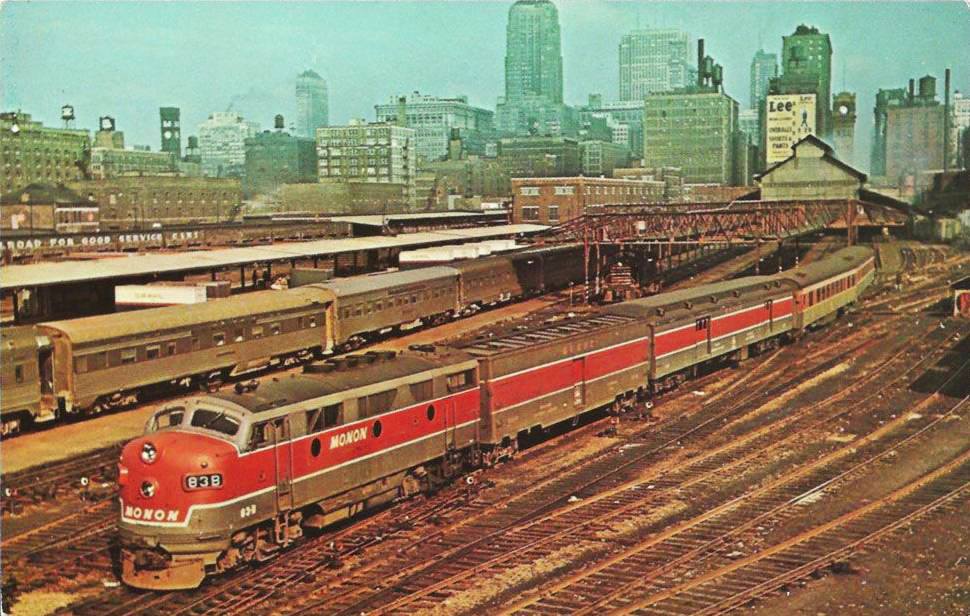

Monon F3A #83-B with what is likely the "Thoroughbred" departing Chicago's Dearborn Station circa 1960. Note that a few blocks over you can see the clock tower of Baltimore & Ohio's Grand Central Station.

Monon F3A #83-B with what is likely the "Thoroughbred" departing Chicago's Dearborn Station circa 1960. Note that a few blocks over you can see the clock tower of Baltimore & Ohio's Grand Central Station.Formation

From an early period the LNA&C was recognized as the "Monon Route," dating back to 1879 when the community of Bradford changed its name to Monon. While it took more than 70 years for this moniker to become the railroad's official title, most simply always knew the modern Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville by its historic nickname.

The LNA&C of 1881 had soon reached Louisville via Pennsylvania Railroad's Jeffersonville Bridge, allowing it access to new terminal property in the city. This was a rather roundabout setup, though, requiring trains to travel a few miles east of New Albany before crossing the Ohio River.

A more direct route lay in the Kentucky & Indiana Bridge under construction at New Albany (it opened in 1886) but for the time being the PRR arrangement remained. After achieving Louisville, the railroad sought a much more ambitious goal, expanding into the rich Appalachian coalfields of eastern Kentucky/western Virginia.

This project would see a new line pushed southeastward from Louisville to the Abingdon/Wytheville, Virginia area. It probably came as a surprise to the region's most dominant carrier, Louisville & Nashville, the small, 451-mile LNA&C was looking to potentially threaten its dominance in the Bluegrass State.

Branches & Black Diamonds

The Monon was largely a linear network of two main lines; Louisville/New Albany - Michigan City and Indianapolis - Chicago.

However, it did operate three notable branches: the first was acquired on March 1, 1886 when the LNA&C picked up the small 17.7-mile Orleans, Paoli & Jasper Railway connecting Orleans with the resorts at French Lick Springs (the OP&J had failed intentions of reaching Evansville, Indiana); the second was a 3-foot narrow-gauge acquired on April 1, 1886 to reach Indiana's coalfields.

In another excellent book by Dr. Hilton entitled, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," it was known as the Bedford & Bloomfield (B&B) with a history dating back to the Bedford, Springville, Owensburg & Bloomfield Railroad organized on November 9, 1874.

It was projected to serve limestone quarries and coal mines but its poor physical plant precluded it from being successful at either (the line's one tunnel near Owensburg, a 1,368-foot bore, even contained a waterfall from an underground spring!).

The line opened on March 1, 1877 running from Switz City to Bedford. After the LNA&C took control it soon standard-gauged the property and spent a great deal of money attempting to improve operations.

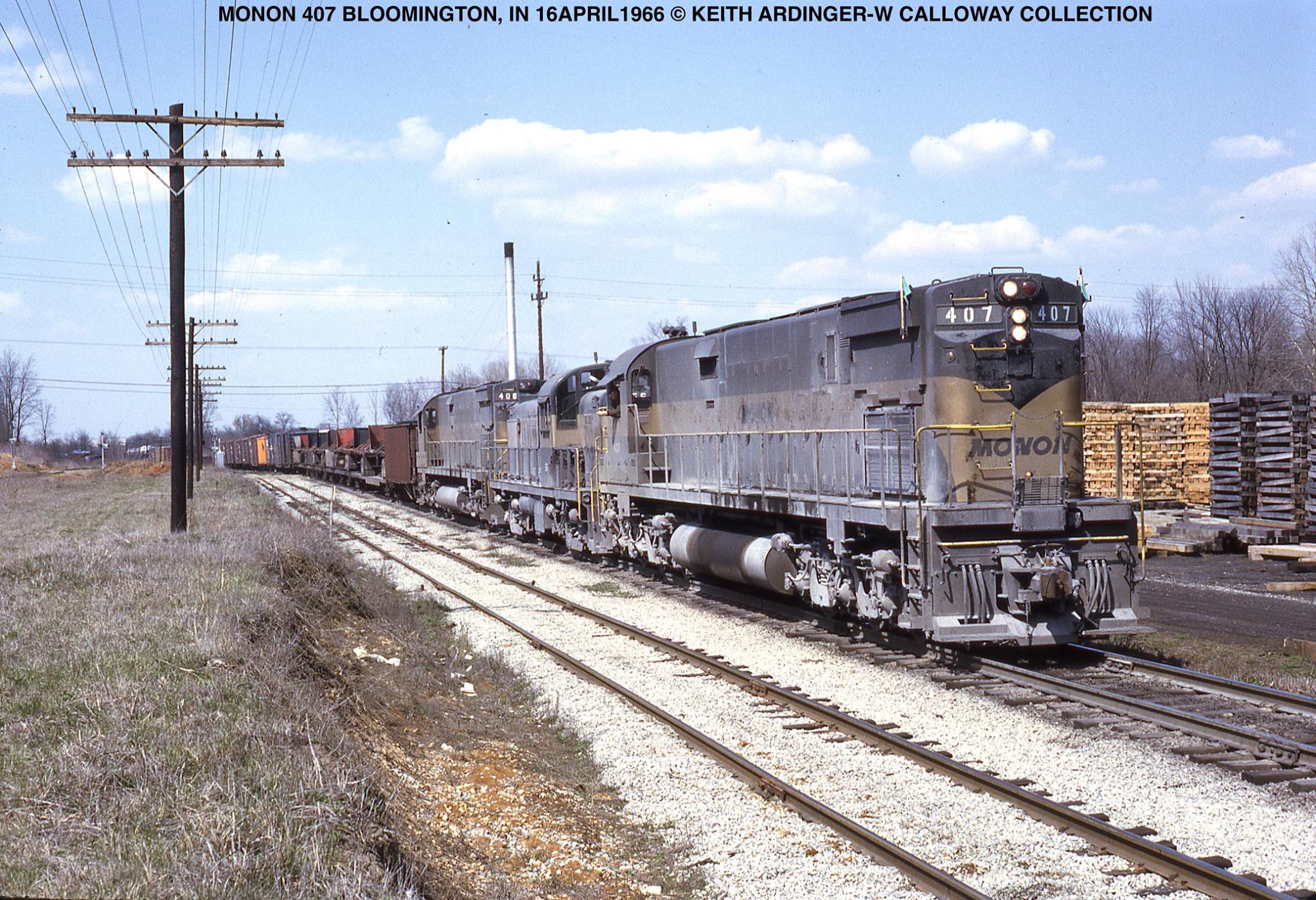

A pair of Monon's huge C628's, along with an RS2, lead a mixed freight through Bloomington, Indiana on April 16, 1966. Acquired new in 1964, the big Centuries proved problematic; their long wheelbases could not easily negotiate Monon's network and their extreme weight had a tendency to spread the rails. In addition, they were no longer needed after the Interstate Commerce Commission refused the coal transfer project the railroad was attempting to launch between the Ohio River and Lake Michigan (Michigan City). They were subsequently returned to Alco in 1967 and later sold to the Lehigh Valley. Keith Ardinger photo/Warren Calloway collection.

A pair of Monon's huge C628's, along with an RS2, lead a mixed freight through Bloomington, Indiana on April 16, 1966. Acquired new in 1964, the big Centuries proved problematic; their long wheelbases could not easily negotiate Monon's network and their extreme weight had a tendency to spread the rails. In addition, they were no longer needed after the Interstate Commerce Commission refused the coal transfer project the railroad was attempting to launch between the Ohio River and Lake Michigan (Michigan City). They were subsequently returned to Alco in 1967 and later sold to the Lehigh Valley. Keith Ardinger photo/Warren Calloway collection.A further issue was B&B's location, based just east of the coalfields which required trackage rights over the Indiana & Illinois to reach mines near Little Giant and Andromeda. Such a setup was not a long-term solution. To correct the problem the LNA&C formed the Indianapolis & Louisville Railroad on March 20, 1899.

While it never reached Evansville, as intended, it did complete a 47-mile segment from Wallace Junction to Victoria in October of 1907.

This corridor offered a right-of-way capable of handling heavy coal tonnage and enjoyed many years of strong business (about 1 million tons annually) although carried just a fraction of the Appalachian seams.

The railroad went on to establish short branches to Gilmore, Cass, and Rainbow along with the previous mines served.

With the opening of this line the old B&B was abandoned from Avoca to Switz City in 1935; a further retrenchment occurred in 1943 when the stretch from Avoca to Dark Hollow was also removed. The entire branch was finally pulled up entirely in 1981.

An American Locomotive builder's photo of new Monon C420 #505 at Schenectady, New York; August, 1966.

An American Locomotive builder's photo of new Monon C420 #505 at Schenectady, New York; August, 1966.But with new ownership in the form of John Jacob Astor III, financing would not a problem leaving L&N with few options to block the endeavor aside from refusing interchange at Louisville. It all began in 1888 when the Louisville Southern (LS) was leased, which extended away from its home city to Lawrenceburg.

From there an LS subsidiary, the Lexington Extension Railroad, provided through service to Lexington. Finally, the Richmond, Nicholasville, Irvine & Beattyville Railroad ("The Riney-B") would complete the corridor east to Beattyville and then south to Cumberland Gap along the borders of Virginia and Tennessee.

A great deal of the Riney-B was completed by 1890 having reached Irvine (about 60 miles). Alas, just when it all seemed assured, fate had other plans.

At A Glance

Louisville - Bedford - Lafayette - Monon - Michigan City, Indiana Indianapolis - Monon - Chicago Wallace Junction - Little Giant/Andromeda/Rainbow/Gilmore (coal branches) Orleans - French Lick Springs Bedford - Avoca | |

Freight Cars: 2,609 Passenger Cars: 59 | |

Astor passed away unexpectedly on February 22, 1890 and with his death the venture collapsed. Taking contorl was a relatively obscure figure who had no interest in continuing the coalfield project.

Dr. William Breyfogle, who owned the largest block of shares at that point, immediately stopped the expansion. He ordered the sale of the everything east of Louisville, replaced top management, and essentially returned the LNA&C to a relatively local carrier dependent upon the L&N for interchange traffic.

Astor's death and the Breyfogle incident relegated the modern Monon to a rather insignificant Midwestern regional.

In time, the coalfields around Cumberland Gap proved incredibly rich, capable of supporting four railroads (L&N, Norfolk & Western, Southern, and the small [but wealthy] Interstate Railroad) for many, many years. Tonnage was heavy for the L&N it would eventually double-track its main line into the region.

Streamliners

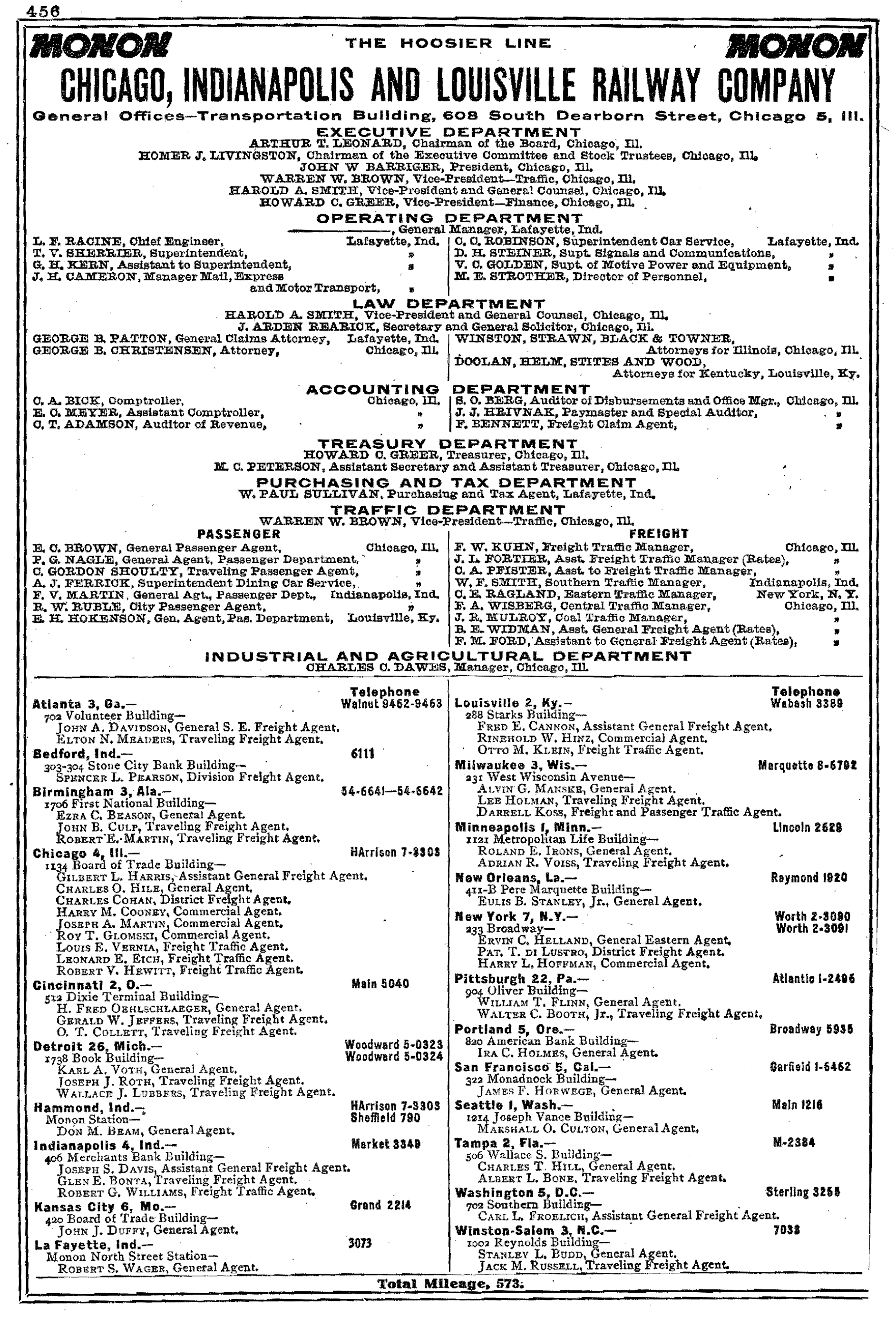

For a line of its size, Monon did boast a handful of streamliners thanks to the work of John Barriger III; most notable of these included the Thoroughbred, Tippecanoe, Hoosier, and Varsity.

Under his direction the company vastly improved operations and was able to dive into the streamliner fad itself, albeit not with new equipment.

In their book, "Monon: The Hoosier Line," authors Gary Dolzall and Stephen Dolzall note the railroad purchased a total of 28 second-hand U.S. Army hospital cars through the spring of 1947 for this purpose.

They were rebuilt at the company shops in Lafayette into streamlined coaches, diner-lounge-parlors, standard parlors, and a single business car wearing an attractive red, white, and grey livery. In addition, a matching set of eight F3A's were purchased to lead the consists.

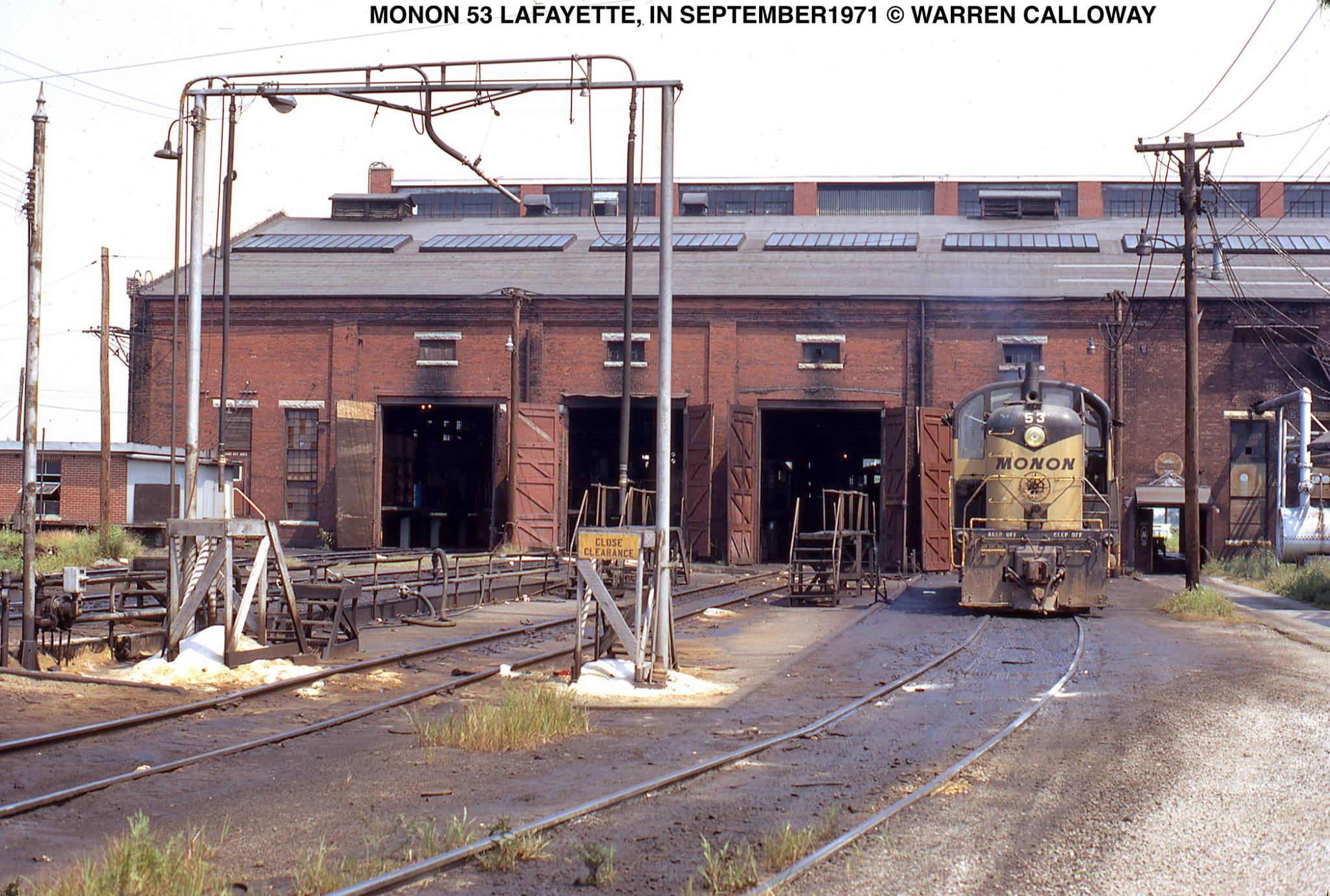

Monon RS2 #53 sits outside the shop in Lafayette, Indiana in September, 1971. Warren Calloway photo.

Monon RS2 #53 sits outside the shop in Lafayette, Indiana in September, 1971. Warren Calloway photo.The trains featured a rather simple but attractive livery of two-tone grey offset by red with white trim. Both the Hoosier and Tippecanoe operated as local/regional runs providing two daily round trips between Chicago and Indianapolis via Monon.

The Thoroughbred, however, served Chicago and Louisville, via Lafayette on a route that was around 324 miles offering connections to other eastern/southeastern trains if they so chose.

For instance, in the case of the Thoroughbred (train #5, southbound) it left Chicago's Dearborn Station daily at 1 P.M. arriving in Louisville eight hours later at 9 P.M.

Its companion, #4 northbound, left Louisville at 9:30 A.M. and arrived back in Chicago by 5:15 P.M. As passenger service continued to slump the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the discontinuance of the last two trains in 1967.

The Thoroughbred made its final runs that year on September 29th (southbound) and 30th (northbound). In an ironic twist, the Monon had made history as the last system to purchase a locomotive for passenger service when it took delivery of two C420's (#501-502) in August of 1966.

Passenger Trains

Daylight Limited: Chicago - Indianapolis

Hoosier: Chicago - Indianapolis

Midnight Special: Chicago - Indianapolis

Night Express: Chicago - Louisville

Red Devil: Operated in Conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad between Indianapolis and French Lick.

Thoroughbred: Chicago - Louisville

Tippecanoe: Chicago - Indianapolis

Varsity: Chicago - Bloomington

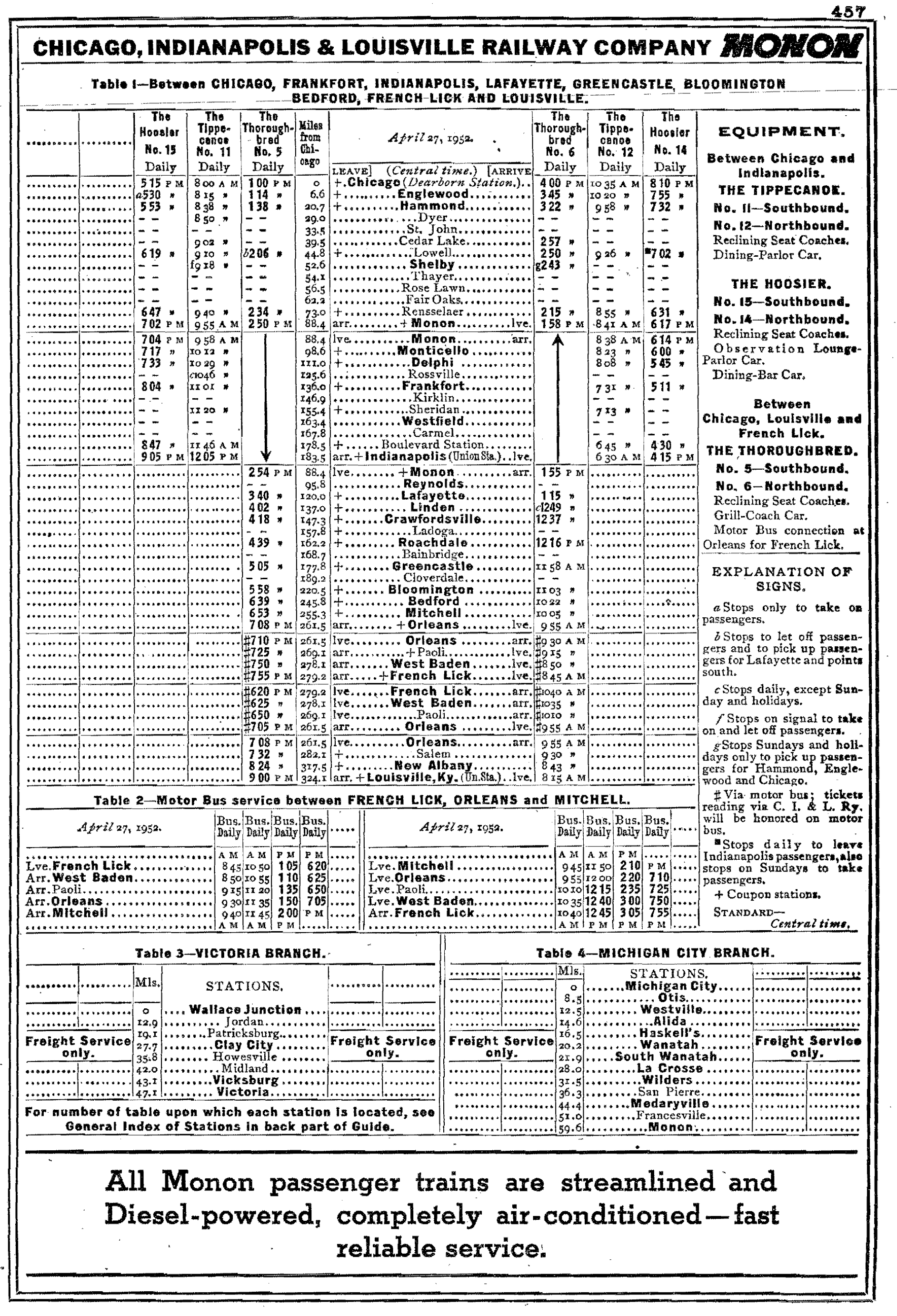

Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway

Despite its many mistakes, the Monon was doing relatively well by the late 19th century. One of its few setbacks occurred following the Breyfogle boondoggle (his erratic management eventually led to his ouster) where the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago entered receivership on August 24, 1896.

It was then reorganized as the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway (CI&L) on March 31, 1897. CI&L's first major step was to improve a severe, 2.27% grade just south of Bloomington.

To eliminate this impediment a 9.4-mile bypass was built and completed on June 1, 1899 (the original line ended through service in early 1940 and was abandoned in 1945).

Its second notable endeavor was to gain a better entry into Louisville; in 1900 it acquired a one-third control of the Kentucky & Indiana Bridge & Railroad Company (in 1910 its name was changed to the Kentucky & Indiana Terminal Railroad) in partnership with the Southern and Baltimore & Ohio.

The massive, double-tracked span not only offered a direct link into the "Gateway To The South" but also offered access to Louisville Union Station.

In 1902 the L&N and Southern acquired majority control of the CI&L, an ownership that would last throughout the company's corporate existence.

Ironically, the new owners maintained a relatively hands-off approach since their subsidiary carried few incentives in which to route traffic that direction; its Chicago line, at 325 miles, was longer than any surrounding road's and, as previously discussed, its profile less than ideal.

The modern Monon remained relatively unchanged throughout the 20th century relying on interchanging business and what coal traffic it could muster. (Interestingly, despite its Midwestern location, agriculture played only a very minor role. While it handled everything from manufactured goods to limestone, products such as grain and corn were inconsequential.)

The Great Depression resulted in another bankruptcy when the CI&L entered receivership again on December 30, 1933. It spent more than a decade mired in reorganization until finally exiting on May 1, 1946 as the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway.

The new man in charge was John Barriger III who proved a stark contrast to anything the company had previously seen. He believed strongly in a railroad's public image, well-maintained physical plant, and the highest-quality customer service. While somewhat handicapped given the railroad's nature, Barriger's efforts proved successful in returning it to profitability.

He overhauled the company's rolling stock and was so fast in retiring the iron horse that steam-powered service was discontinued just three years after his arrival. The last unit dropped its fire on October 15, 1949. The CI&L was not strong enough to implement many of the grade and track improvements Barriger wanted but he did what he could.

- An attempt to bypass all four street-running locations [Bedford, Lafayette, Monticello, and New Albany] was simply too expensive as did a plan to improve grades and curves south of Monon. However, he was able to upgrade the bridge over the Wabash River at Delphi and bypass a swamp-infested region around Cedar Lake. -

In an attempt to prop up sagging passenger numbers he introduced new streamliners (utilizing rebuilt heavyweight cars) and unveiled liveries honoring the state's home universities; red, white, and grey (the passenger livery) highlighted Wabash College and Indiana University while black and gold (the freight scheme) featured Purdue University and DePauw University.

The passenger angle was Barriger's least successful as business continued to slide, so much so that he cancelled remaining night trains #3 and #4 after September 25, 1949.

Perhaps his most ambitious, and certainly most intriguing, plan was to have the Monon merge with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois; Toledo, Peoria & Western; and Minneapolis & St. Louis.

As author Don Hofsommer's notes in his book "The Tootin' Louie: A History Of The Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway," the idea was to essentially create a gigantic Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railway to bypass congested Chicago. Unfortunately, the scheme went nowhere due to stiff opposition (Ben Heineman tried a similar tactic during his stint at M&StL that also failed).

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS2 | 21-29 | 1/1947 - 10/1947 | 9 |

| C628 | 400-408* | 3/1964 | 9 |

| C420 | 501-502** | 8/1966 | 2 |

| C420 | 503-506 | 8/1966 | 4 |

| C420 | 507-518 | 8/1967 | 12 |

* Their six-axle wheelbases were far too long to negotiate the Monon's network while their extreme weight had a tendency to spread the rails.

In addition, their entire purpose was proved moot when the ICC refused the coal transfer project the railroad was attempting to launch between the Ohio River and Lake Michigan (Michigan City). They were returned to Alco in 1967 and later sold to the Lehigh Valley.

** Featured a high, short-hood equipped with a steam-generator for passenger service.

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| NW2 | DS-1, DS-2, DS-3 | 1/1942 | 3 |

| NW2 | 14-17 | 1/1947 | 4 |

| BL2 | 30-38 | 4/1948-5/1949 | 9 |

| SW1 | DS-50 | 2/1942 | 1 |

| SW1 | 5-6 | 8/1949 | 2 |

| F3A | 51A-52A, 51B-52B, 61A-64A, 61B-64B, 81A-85A, 81B-85B | 12/1946 - 5/1947 | 22 |

| F3A | 62B, 64A (2nd*) | 3/1948 | 2 |

| F3B | 61C-65C, 64C (2nd*) | 12/1946 - 10/1947 | 6 |

* These units replaced the originals involved in a horrific collision at Ash Grove near the Lafayette Shops on June 3, 1947.

Fairbanks-Morse

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H10-44 | 18 | 11/1946 | 1 |

| H15-44 | 36-37 | 9/1947 - 12/1947 | 2 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U23B | 601-608 | 3/1970 - 4/1970 | 8 |

Electric Locomotive Roster

| Road Number | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | B-B | McGuire-Cummings | 1915 |

This unit's entire purpose was to operate a short spur owned by the Terre Haute, Indianapolis & Eastern Traction to serve the interurban's powerhouse in Crawfordsville.

Dr. Hilton and John Due's book, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," notes that the THI&ET was the second-largest such system in its home state with a network of 402 miles spread throughout central Indiana.

It was formed on March 1, 1907 through the merger of four smaller systems; despite its large size it struggled mightily due to an extensive branch line network and relatively weak freight earnings.

The Monon discontinued use of its only electric locomotive shortly after World War I and the THI&ET shutdown entirely during January of 1932.

Steam Roster

| Road Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-5 | B-1 | 0-6-0 | Brooks | 6/1885 |

| 6 | B-2 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 12/1892 |

| 7-8 | B-4 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 5/1893 |

| 9-10 | B-6 | 0-6-0 | Brooks | 6/1897 |

| 12 (First) | - | 0-6-0 | Rogers | 3/1890 |

| 11-13 | B-7 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 1/1902 |

| 18-24 | B-8 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 2/1905-12/1907 |

| 26-35 | G-3, G-4 | 4-6-0 | Rogers | 11/1880-8/1881 |

| 36 | G-1 | 4-6-0 | Baldwin | 6/1893 |

| 37-39 | B-9 | 0-6-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1923 |

| 52-53 | - | 0-4-0 | Rogers | 12/1882 |

| 60-63 | F-1 | 2-6-0 | Brooks | 12/1884-5/1885 |

| 64-67 | - | 2-8-0 | Rhode Island | 1/1887-2/1887 |

| 68, 70 | B-3 | 0-6-0 | Rhode Island | 2/1887 |

| 69 | - | 4-4-0 | Rogers | 6/1873 |

| 71 | - | 4-4-0 | Brooks | 6/1884 |

| 72-76, 93-97 | H-1 | 2-8-0 | Rogers | 10/1887-12/1890 |

| 77-81, 87-92 | G-2, G-5 | 4-6-0 | Rogers | 1/1890-6/1890 |

| 82-88 | D-5 | 4-4-0 | Rogers | 8/1889-2/1891 |

| 82-86 (Second) | H-2 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 4/1892-6/1892 |

| 107-108 | D-4 | 4-4-0 | Baldwin | 4/1892-6/1893 |

| 111-112 | D-7/a | 4-4-0 | Brooks | 6/1897 |

| 120-121 | G-6 | 4-6-0 | Brooks | 4/1900 |

| 200-201, 203-204 | E-1/a | 4-8-0 | Brooks | 5/1898-6/1898* |

| 206, 208-209 | E-1/a | 4-8-0 | Brooks | 4/1899-4/1900* |

| 202, 205, 207, 210-211 | E-1/b | 4-8-0 | Brooks | 5/1898-4/1900* |

| 212-221 | E-2/b | 4-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 1/1902-11/1903 |

| 250-255 | H-4 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1904-2/1905 |

| 256-258 | H-5 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 5/1906 |

| 285-291 | H-6 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 5/1911 |

| 300-301 | I-1 | 4-4-2 | Brooks | 10/1901 |

| 350-354 (First) | H-3 | 2-8-0 | Alco/Brooks | 10/1910 |

| 350-353 (Second) | K-1/a | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 11/1905 |

| 354-359 | K-2/a | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 4/1906-1/1907 |

| 400-402 | K-3 | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 6/1909 |

| 403-405 | K-4 | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 5/1911 |

| 440-445 | K-5 | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 9/1912-11/1923 |

| 450-452 | K-6 | 4-6-2 | Alco/Brooks | 11/1916 |

| 500-533 | J-1 | 2-8-2 | Alco/Brooks | 3/1912-1/1923 |

| 550-554 | J-2 | 2-8-2 | Alco | 12/1918 |

| 560-565 | J-3 | 2-8-2 | Alco/Rogers | 10/1926 |

| 570-579 | J-4 | 2-8-2 | Alco | 10/1929 |

| 600-604 | L-1 | 2-10-2 | Alco | 11/1914 |

| 605-606 | L-1 | 2-10-2 | Alco/Brooks | 11/1916 |

* Originally classed E-1, these Twelve-wheelers were rebuilt and sub-classed between January of 1922 and August of 1926.

Narrow-Gauge Steam Roster

Bedford, Springville, Owensburg & Bloomfield

| Road Number/Name | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (First) | 0-4-0 | Porter, Bell & Company | 4/1875 |

| 2 (Bloomfield) | 0-6-0 | Porter, Bell & Company | 3/1876 |

| 1 (Second)/(Bedford) | 2-4-0 | Porter, Bell & Company | 3/1876 |

| 3 (W.O. Rockwood) | 2-4-0 | Porter, Bell & Company | 2/1880 |

| 4 (John Thomas) | 2-4-0 | Porter, Bell & Company | 7/1881 |

Indianapolis, Delphi & Chicago

| Road Number/Name | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 (Alfred M. McCoy) | 4-4-0 | Baldwin | 11/1877 |

| 5 (Rowland Hughes) | 4-4-0 | Baldwin | 5/1878 |

The above rosters are gleaned largely from George Hilton's authoritative book, "Monon Route." This is only a simplified listing.

Final Years

At the end of 1952, Barriger left to become vice president of the New York, New Haven & Hartford bringing an end to the railroad's most colorful and successful era. A few years after his departure, on January 10, 1956, it formally changed its name to the "Monon Railroad."

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s it remained a top-rate company, albeit always a David surrounded by Goliaths. As the merger movement gained momentum officials realized they had to find a partner or be left to wither among the giants.

This was a difficult prospect due to the big carriers showing little interest. One last ditch effort to carve out a niche for itself involved running unit coal trains from the Ohio River to Michigan City; it seemed promising but the Interstate Commerce Commission denied the plan. With this defeat the railroad essentially gave up independence and sought inclusion with a large Class I.

It managed to work out a deal with the Louisville & Nashville and was acquired by the Hoosier Line on July 31, 1971. While the Monon remained relatively obscure for most of its life it is well-remembered and beloved within the communities it served as Indiana's railroad.

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin Christmas Train Rides In Trego!

Dec 16, 25 07:22 PM

Among the Wisconsin Great Northern's most popular excursions are its Christmas season offerings: the family-friendly Santa Pizza Train and the adults-only Holiday Wine Train. -

Vermont's 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides

Dec 16, 25 07:16 PM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Rhode Island's 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides

Dec 16, 25 06:50 PM

It may the smallest state but Rhode Island is home to a unique and upscale train excursion offering wide aboard their trips, the Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad.