Missouri Pacific Railroad, "Route Of The Eagles!"

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Missouri Pacific's corporate history is an intriguingly complicated affair involving numerous twists, turns, subsidiaries, and bankruptcies.

The modern company was comprised of several noteworthy predecessors like the Texas & Pacific, International-Great Northern, and St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern.

For these reasons, the MoPac's complete story could fill many volumes; even those systems previously mentioned have been thoroughly covered in books and magazines. As a result, any attempt to do so here would be impossible.

In short, the MP owned a web of main lines and secondary corridors which were spread out across Missouri, Kansas, eastern Colorado, eastern Nebraska, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana. While the railroad failed to reach its namesake ocean it later achieved a direct route into Chicago.

The railroad's corporate history was one financial mess after another. However, following World War II it made dramatic transformation into a profitable Midwestern carrier.

Its new success and the mega-merger movement led to its 1982 acquisition by Union Pacific. Today, its 12,000-mile network comprises a significant component of the country's largest and most powerful railroad.

Photos

Missouri Pacific PA-2 #67 (built as #8024) receives attention at the railroad's shops in St. Louis - located along Choteau and Ewing Avenues - on November 26, 1967. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific PA-2 #67 (built as #8024) receives attention at the railroad's shops in St. Louis - located along Choteau and Ewing Avenues - on November 26, 1967. American-Rails.com collection.History

The Missouri Pacific's immediate ancestry can be traced back to the Pacific Railroad. According to Joe Collias's book "Frisco Power: Locomotives And Trains Of The St. Louis-San Francisco Railway, 1903-1953," it was chartered in March of 1849 by the State of Missouri to link St. Louis with the Pacific coast.

The project was ambitious but formidable with numerous challenges, the most critical of which was procuring a steady flow of capital. Even the prospect of laying a grade was extremely difficult due to the region's remoteness, sparse population, and lack of infrastructure. Nevertheless, promoters pressed forward.

In his book, "Missouri Pacific Lines: Freight Train Services And Equipment," author Patrick Dorin notes ground was broken in St. Louis on July 4, 1851. The initial goal involved following the Missouri River's south bank to reach Kansas City.

The company's first locomotive, named Pacific (built by the Taunton Locomotive Manufacturing Company of Taunton, Massachusetts), arrived on August 20, 1852; shortly thereafter the first 5 miles from St. Louis to nearby Cheltenham opened.

On December 9th the company's inaugural train, also credited as the first to operate west of the Mississippi River, chugged down this track carrying local dignitaries and officials.

At A Glance

St. Louis - Sedalia - Kansas City - Omaha Jefferson City - Boonvile - Kansas City St. Joseph, Missouri - Stockton, Kansas Kansas City - Pueblo, Colorado Osawatomie, Kansas - Wagoner, Oklahoma - North Little Rock, Arkansas Pleasant Hill, Missouri - Wichita - Geneseo, Kansas Fort Scott - Larned, Kansas Rich Hill - Joplin, Missouri Carthage, Missouri - Diaz, Arkansas St. Louis - Little Rock - Texarkana, Texas East St. Louis, Illinois - Poplar Bluff, Missouri Bismarck, Missouri - Salem, Illinois Bald Knob, Arkansas - Memphis Little Rock - McGehee, Arkansas - Lake Charles, Louisiana Memphis - McGehee McGehee - Vidalia, Louisiana Pine Bluff - Hot Springs, Arkansas Gurdon, Arkansas - Clayton, Louisiana Longview - Laredo, Texas Palestine - Galveston, Texas Brownsville, Texas - Baton Rouge - New Orleans New Orleans - Donaldson - Alexandria, Louisiana Fort Worth - Houston San Antonio - Corpus Christi, Texas El Paso - Longview - Livonia, Louisiana - New Orleans Fort Worth - Cypress, Louisiana Texarkana - Longview | |

New Orleans, Texas & Mexico Railway Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western Railway Orange & Northwestern Railroad St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico Railway New Iberia & Northern Railroad Houston & Brazos Valley Railway International-Great Northern Railroad San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf Railroad Sugar Land Railway Rio Grande City Railway Asherton & Gulf Railway San Antonio Southern Railway Asphalt Belt Railway Iberia, St. Mary & Eastern Railroad San Benito & Rio Grande Valley Railway Houston North Shore Railway Texas & Pacific Railway |

|

Freight Cars: 44,923 Passenger Cars: 533 | |

During July of 1853 the line was extended west to Franklin, Missouri (now known as Pacific), a distance of 38 miles. Unfortunately, funding could not be sustained and construction stalled.

In his book, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III," author and historian Mike Schafer notes that to secure further funding the Southwest Branch of the Pacific Railroad was incorporated for the purpose of opening a southwestern corridor from Franklin to Rolla.

Logos

Construction of this segment began on July 19, 1853 but required upwards of seven years before it was finally completed in 1860. In 1855, work on the original PR resumed as it reached Jefferson City. Progress, though, was interrupted again by the Civil War's outbreak.

Shortly after hostiles ended the railroad finally reached Kansas City (September 19, 1865) but with damage sustained by Confederate raiders, coupled with further financial difficulties, the entire PR system was placed under Missouri state control during February of 1866.

Then, a few months later (June/1866) the original Pacific Railroad (St. Louis-Kansas City) was sold while the Southwest Branch fell into General John Fremont's hands.

Missouri Pacific GP35's, with #620 out front, lead a northbound past the yard at Dupo, Illinois (just south of East St. Louis) on May 18, 1968. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific GP35's, with #620 out front, lead a northbound past the yard at Dupo, Illinois (just south of East St. Louis) on May 18, 1968. American-Rails.com collection.Jay Gould

The former was reorganized as the Missouri Pacific Railway (1872) while the latter became the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway (1876), better remembered as the "Frisco."

By then, Jay Gould had made a name for himself as a shady but successful Wall Street speculator; he first entered the railroad industry during 1859 and within a decade had blossomed into an influential tycoon.

Of his early escapades, battling the powerful Cornelius Vanderbilt for control of the Erie Railway is the best-remember. Also known as the "Erie War," Gould eventually defeated the Commodore for control of the company before being ousted, himself, as president in 1872.

A year later, he set his sights west and acquired the recently-completed Union Pacific in 1873; later that decade the Denver & Rio Grande, Kansas Pacific, Denver Pacific, and a few others were added to his growing network.

For his many faults, Gould is credited with establishing many of the classic systems we know so well today; names like the Wabash, Katy, Rio Grande, and Wheeling & Lake Erie.

This was also true with the Missouri Pacific, which he acquired in 1879. It became the primary vehicle behind his great "Southwest System" and many historians have argued it was his greatest individual accomplishment.

Missouri Pacific SD40-2 #3117 leads a long freight through western Kansas in the winter of 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific SD40-2 #3117 leads a long freight through western Kansas in the winter of 1974. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

Afterwards, four notable systems joined the MoPac: the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern (StLIM&S); Texas & Pacific (T&P); International & Great Northern (I&GN); and finally the Missouri, Kansas & Texas ("Katy").

While a court order forced him to divest control of the latter in 1888 he used the quartet to greatly increase his presence throughout Texas. Until the Santa Fe reached the Lone Star State in 1887, Gould boasted a virtual monopoly here.

The other three systems have their own interesting stories, far too long to cover in any great detail within this article. In short, they comprised the bulk of Missouri Pacific's network.

The StLIM&S began as the St. Louis & Iron Mountain Railroad (StL&IM), chartered by the state of Missouri on March 3, 1851. In his book, "The Texas Railroad: The Scandalous And Violent History Of The International And Great Northern Railroad, 1866-1925," author Wayne Cline points out that the StL&IM was originally envisioned to exploit iron ore deposits located around Ironton, Missouri.

System Map (1930)

On April 2, 1858 it opened to Pilot Knob (very near Ironton), then continued expanding southwestward. On May 6, 1874 the StL&IM was reorganized as the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern Railway (StLIM&S or "Iron Mountain Route") at which time it leased the Cairo, Arkansas & Texas and Little Rock & Fort Smith.

In 1880, all three came under Gould's control. As a group, these railroads acted as a bridge route, connecting the MP at St. Louis with the T&P at Texarkana, Arkansas/Texas.

This latter point also witnessed interchange traffic from the nearby International & Great Northern (I&GN), which connected with the T&P at Longview. There was arguably no other component quite as important to MoPac's system as the Texas & Pacific.

Its saga began on March 3, 1871 when Congress awarded the then-Texas Pacific Railroad a rare federal charter to establish a southern transcontinental route along the 32nd parallel from Marshall, Texas to San Diego, California.

As with other key projects which began west of the Mississippi River (Union Pacific, Santa Fe, and Northern Pacific) land grants would aid the T&P's development; the government awarded twenty sections per mile through California and forty sections within the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico.

In addition, Texas awarded twenty sections per mile within its borders. On May 2, 1872 the company's name was changed to the Texas & Pacific Railway and just a year later, the first segment between Marshall and Texarkana was completed (December 28, 1873). As it continued expanding westward Jay Gould became involved during the fall of 1879 and subsequently leased it to the MP in 1881.

Missouri Pacific E7A #26 departs St. Louis Union Station with train #17, the "Missouri River Eagle," during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific E7A #26 departs St. Louis Union Station with train #17, the "Missouri River Eagle," during the 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.Under his direction the T&P continued its march, reaching Sierra Blanca in West Texas on December 16, 1881 with a goal of connecting to the Southern Pacific at El Paso. Unfortunately, this was not to be.

The SP, led by Collis P. Huntington, had arrived there a few months earlier on May 19th, then continued building east, reaching Sierrra Blanca on November 25th.

By extending much further than what had been stipulated, Gould took Huntington to court. The fight was finally resolved when the "Gould-Huntington Agreement" was signed on November 26, 1881.

This accord gave the T&P trackage rights over the Southern Pacific into El Paso but also forfeited its charter and franchises west of that point which were awarded to SP. Following the settlement, construction continued eastward with the railroad arriving in New Orleans on September 12, 1882.

In the succeeding years the T&P continued expanding, most notably to Denison (opening an interchange there with the Missouri, Kansas & Texas) and a secondary line into Texarkana that passed through Paris. At its peak the T&P owned 1,982-miles, including 1,109 miles in Texas.

An A-B set of Missouri Pacific E7s, led by #7006, hustle west out of St. Louis with what appears to be train #11, the "Colorado Eagle," during a summer's afternoon in the late 1950s. In the background is the Museum of Transportation, which was just over a decade old in this scene. American-Rails.com collection.

An A-B set of Missouri Pacific E7s, led by #7006, hustle west out of St. Louis with what appears to be train #11, the "Colorado Eagle," during a summer's afternoon in the late 1950s. In the background is the Museum of Transportation, which was just over a decade old in this scene. American-Rails.com collection.As-mentioned, the T&P held a principal connection with the International & Great Northern at Longview. For a fascinating background of this carrier and how it wound up under Gould's direction purchase a copy of Mr. Cline's book.

Its heritage traces back to the Houston & Great Northern Railroad's (H&GN), originally chartered on October 22, 1866 to link Houston with the Red River.

The H&GN was a wholly-owned Texas corporation, spearheaded by Charles Young. On August 9, 1871 the first 25 miles were finished out of Houston but, alas, fate had different plans as Young was killed during an inspection trip that August day.

This resulted in control passing into the hands of New York City investors, who drastically altered the company's direction; on September 30, 1873 it was merged with the International Railroad to form the International & Great Northern Railroad. New ownership then abandoned the Red River project in favor of opening a connection to the T&P.

Missouri Pacific GP7 #230 with an interesting baggage-coach caboose, used in branch line service to handle remaining passenger business; May, 1968. Location not listed. Lee Berglund photo. American-Rails.com

collection.

Missouri Pacific GP7 #230 with an interesting baggage-coach caboose, used in branch line service to handle remaining passenger business; May, 1968. Location not listed. Lee Berglund photo. American-Rails.com

collection.Despite these changes the I&GN did transform into a respectable system reaching Galveston, Columbia, Mineola, Austin, San Antonio, the Mexican border at Laredo, and of course Longview. By 1911 it operated 1,106 miles. In December, 1880 Gould gained control of the I&GN (later leased to the MK&T as of June 1, 1881) and it appeared his grip on Texas was firmly established.

For the time being, however, things did not quite go according to plan for mogul. In 1885, the T&P entered receivership and by losing the MK&T through court-order in 1888 Gould also lost the I&GN. Both setbacks left him only in command of the Iron Mountain and Missouri Pacific.

A former Rock Island GP38-2 is ahead of this Missouri Pacific freight at Vinson Siding near Austin, Texas during the early 1980s. The unit became MoPac #2260. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A former Rock Island GP38-2 is ahead of this Missouri Pacific freight at Vinson Siding near Austin, Texas during the early 1980s. The unit became MoPac #2260. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.For now, he had more pressing matters, specifically the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe. This carrier, led by William Barstow Strong, had quickly established itself as a powerful western railroad. In an effort to combat this threat, Gould engaged in a drawn out battle for control of the agriculture and cattle trade by constructing a tangled web of branch lines across Kansas.

In this regard he did have success. His expansion efforts were so aggressive that, according to the article, "Building The Main Line Of The Missouri Pacific Through Kansas" by A. Bower Sageser, the MoPac had reached Omaha, Nebraska on July 1, 1882 and Pueblo, Colorado on December 2, 1887.

In 1896, Gould's portfolio was handed over to his son, George, who continued his father's transcontinental ambitions.

By the early 20th century the younger tycoon had, once again, nearly accomplished the feat through control of the Missouri Pacific, Western Pacific, Denver & Rio Grande Western, Western Maryland, and Wheeling & Lake Erie along with the Wabash.

However, he, too, suffered the same fate as his father when the financial Panic of 1907 broke up his empire. During March of 1917 a new company was born by merging the original Missouri Pacific Railway; St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern; and a number of smaller carriers into the new Missouri Pacific Railroad.

Afterwards, following the International-Great Northern Railroad reorganization in 1922 it, also joined the MoPac (January 1, 1925).

Missouri Pacific F7A #811, F3B #810-B, and another F7A layover between assignments, circa 1965. Location not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific F7A #811, F3B #810-B, and another F7A layover between assignments, circa 1965. Location not recorded. American-Rails.com collection.Modern Network

The 1920's were a banner decade which witnessed a great deal more expansion. One such system was the so-called "Gulf Coast Lines" (GSL). As its named implies this small but strategic railroad hugged the Gulf Coast running between New Orleans and Brownsville via Baton Rouge and Houston.

After the GSL was added in 1926, management turned its attention to the Texas & Pacific. Despite T&P's 1885 bankruptcy, the two carriers had maintained a close working relationship until the MP finally acquired majority stock control in 1928.

That same year it began marketing itself as the "Missouri Pacific Lines" to better reflect the many subsidiaries comprising the system.

Unfortunately, despite escaping the Goulds' grip the railroad remained hampered by heavy debt and in need of considerable improvements. The stock market crash of 1929 only made matters worse and before long it had slipped into bankruptcy once more.

But, the Great Depression proved a turning point as the MP slowly transformed itself into a modern, respectable, and profitable carrier.

This process had actually began in May of 1928 when a brand new, 22-story headquarters building opened in downtown St. Louis at 210 North 13th Street, designed to streamline the operations of its many subsidiaries.

Missouri Pacific PA-2 #59 (built as #8016) lays over at the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis engine terminal along Scott Avenue, circa 1962. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific PA-2 #59 (built as #8016) lays over at the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis engine terminal along Scott Avenue, circa 1962. American-Rails.com collection.The company's Official Guide listing proudly highlighted these railroads which included:

- New Orleans, Texas & Mexico

- Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western

- Orange & Northwestern

- St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico

- New Iberia & Northern

- Houston & Brazos Valley

- International-Great Northern

- San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf

- Sugar Land Railway

- Rio Grande City Railway

- Asherton & Gulf

- San Antonio Southern Railway;

- Asphalt Belt Railway

- Iberia, St. Mary & Eastern

- San Benito & Rio Grande Valley

- Houston North Shore Railway

As for the Texas & Pacific, it enjoyed its very own listing. As traffic recovered the MoPac began overhauling its network with infrastructure upgrades, improved and expanded freight service (in April of 1938 it launched a trucking division, Missouri Pacific Freight Transport Company), and later centralized traffic control.

- As it name implies, CTC offers safer and more efficient operations by centralizing dispatching in one location. From this point, a dispatcher controls movements over a particular segment of track, i.e., territory. -

Thanks to World War II's incredible traffic blitzkrieg these upgrades continued and by 1955 dieselization was completed.

Rio Grande FTA #5494 and Missouri Pacific GP7 #4149 layover in Pueblo, Colorado during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.

Rio Grande FTA #5494 and Missouri Pacific GP7 #4149 layover in Pueblo, Colorado during the 1950s. American-Rails.com collection.In his book, "The Rebirth Of The Missouri Pacific, 1956-1983," author Craig Miner articulately details how the MoPac became one of the Midwest's most prominent carriers during an era when several others were struggling.

At 12:01 AM on March 1, 1956 it finally exited receivership as the Missouri Pacific Railroad containing a 9,710-mile system. Its last 26 years as an independent entity were defined by strong management and high quality service.

One of the company's most noteworthy leaders at this time was Downing Jenks, elected president in 1961 after spending a few years at the Rock Island.

He fine-tuned the MP into a highly efficient system and was an early proponent of computerization. Throughout the 1960's the railroad perfected the use of electronics, which led to the Transportation Control System (TCS).

Passenger Trains

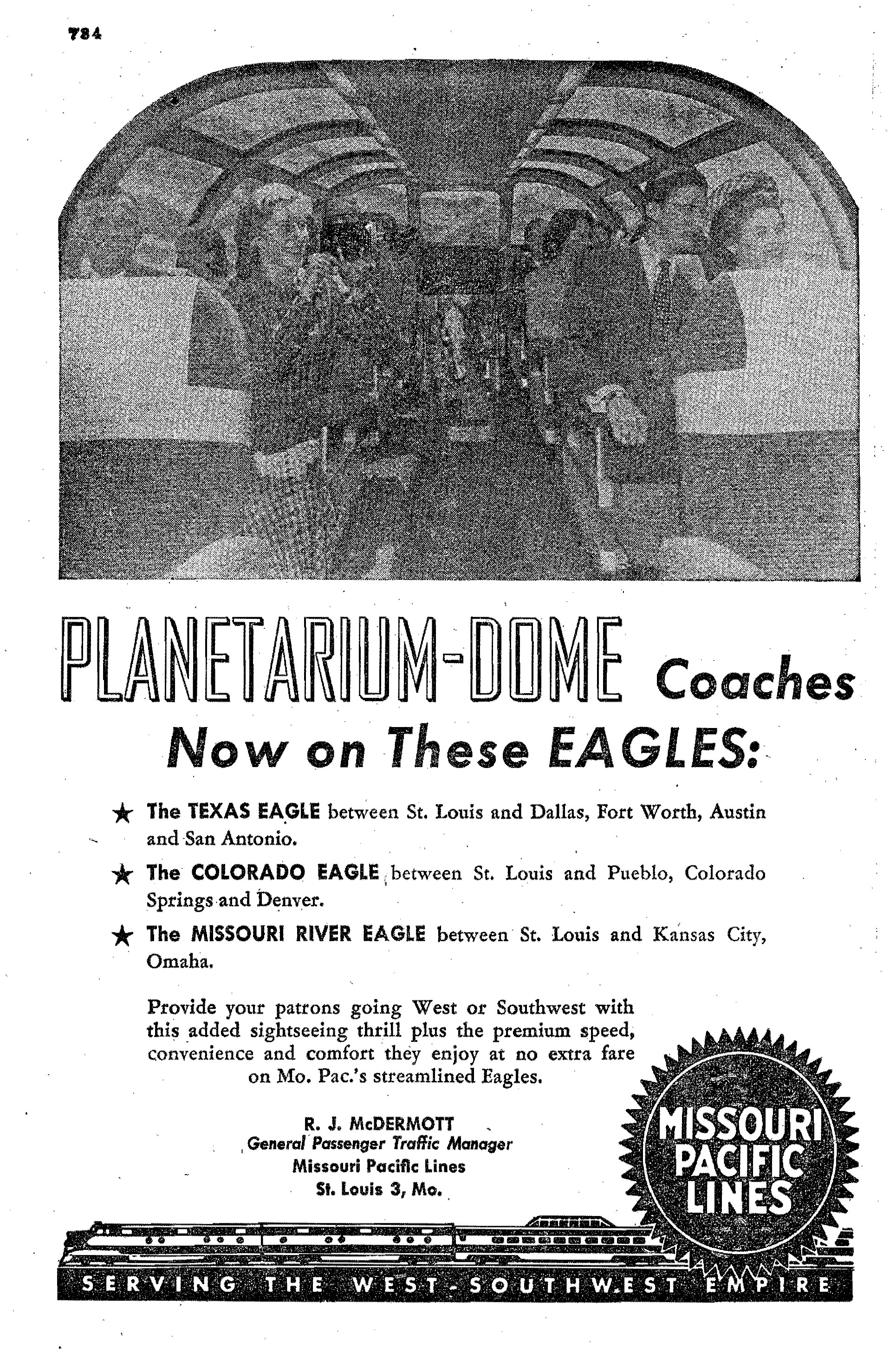

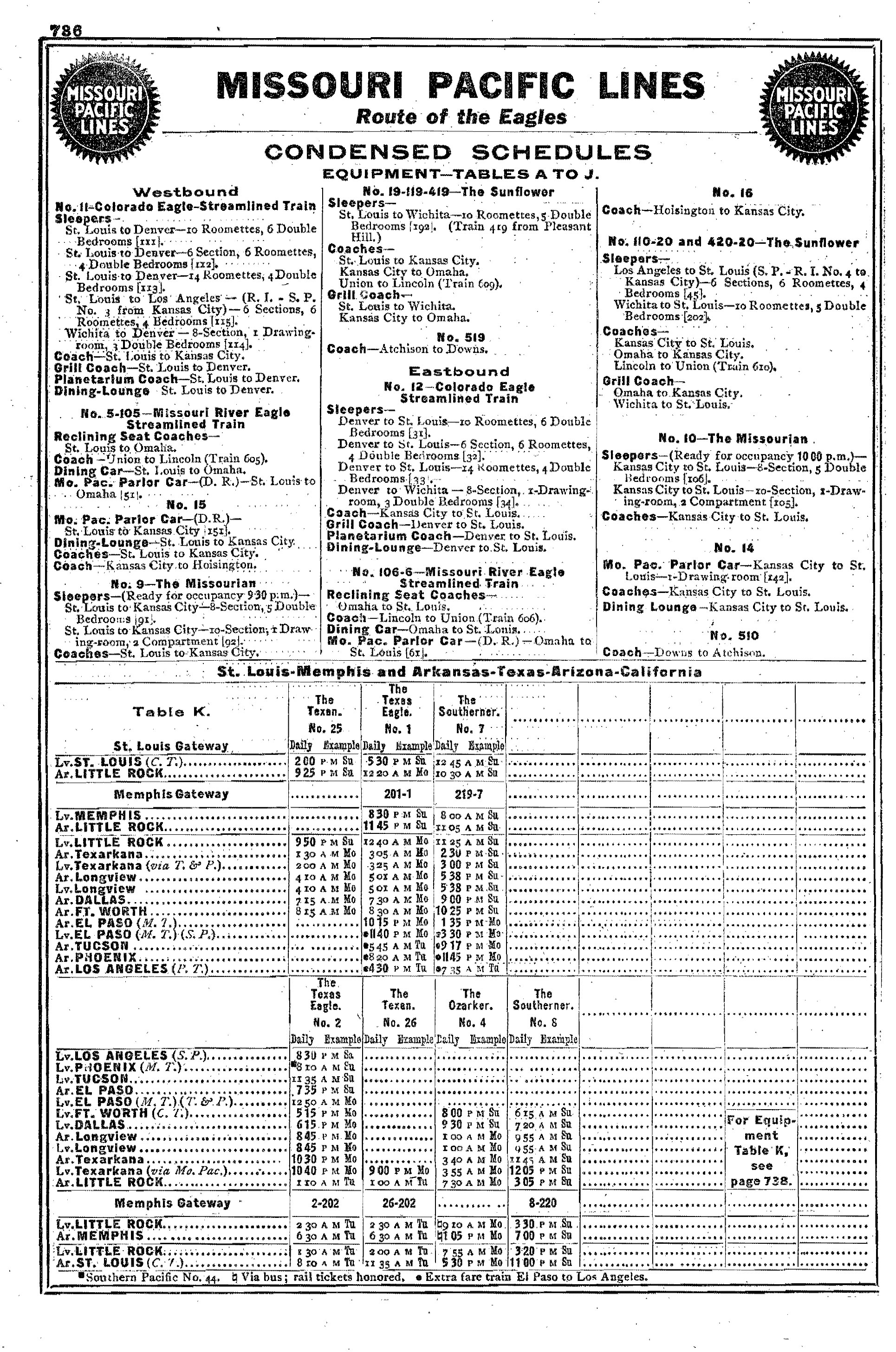

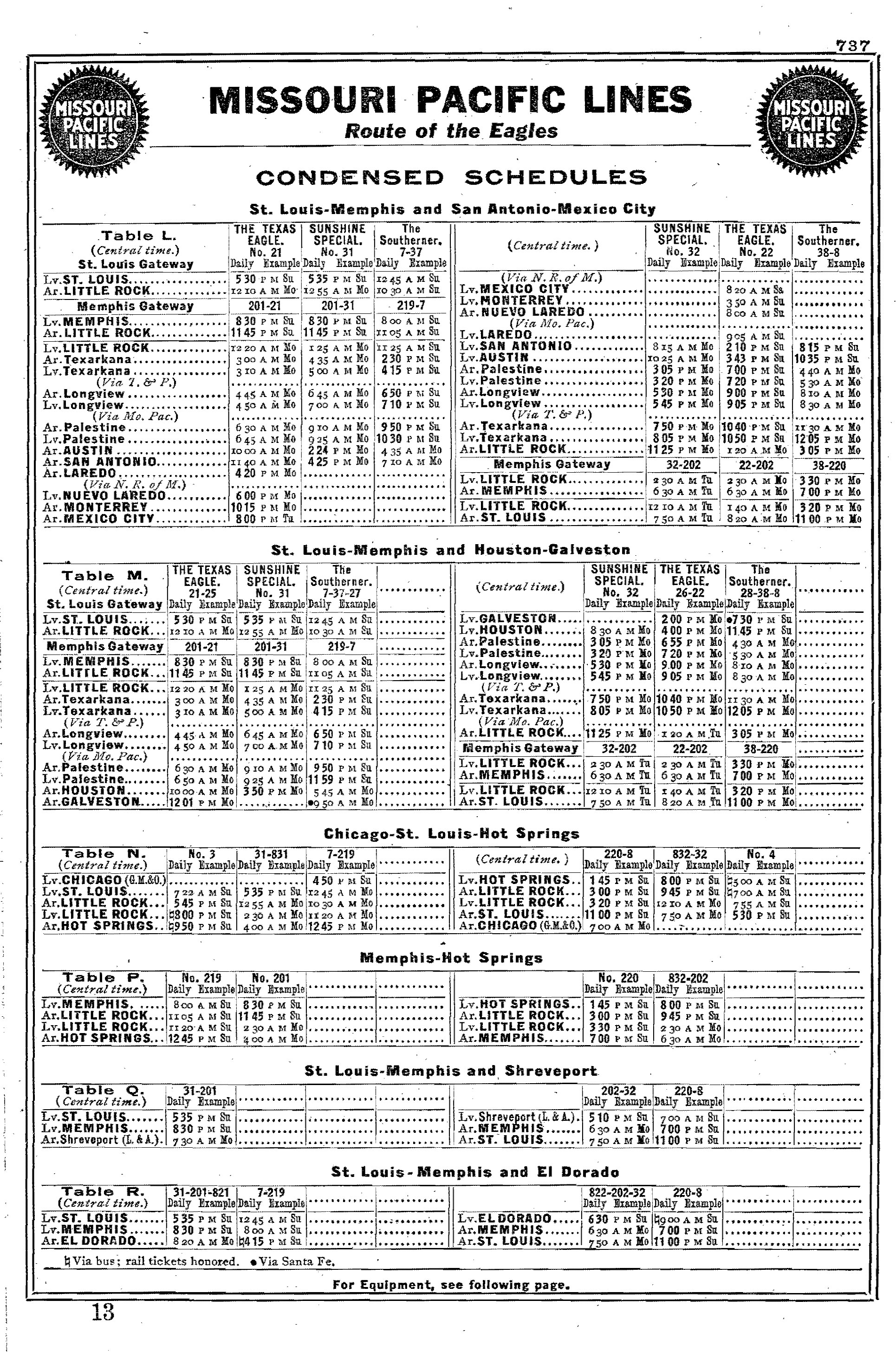

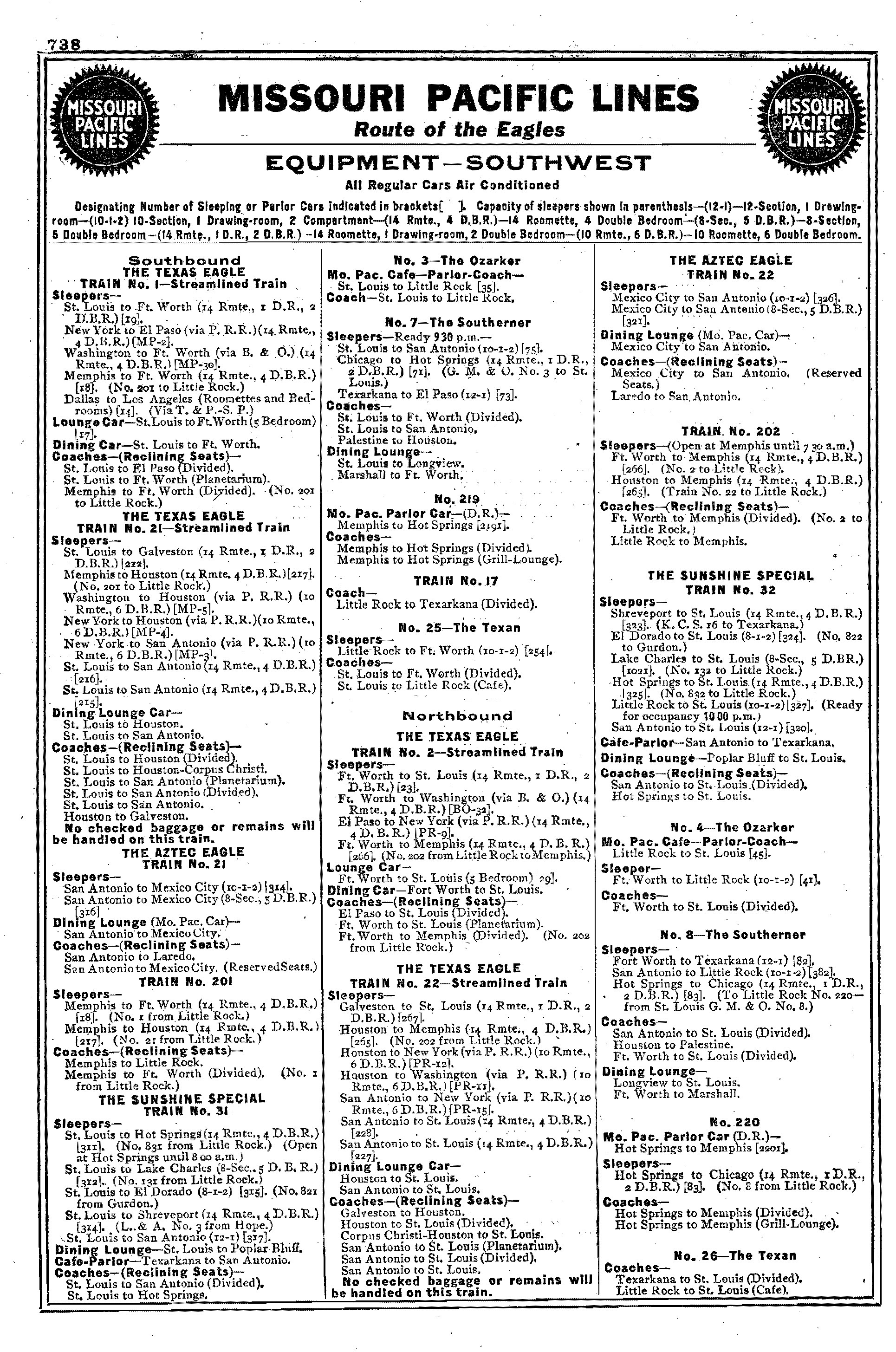

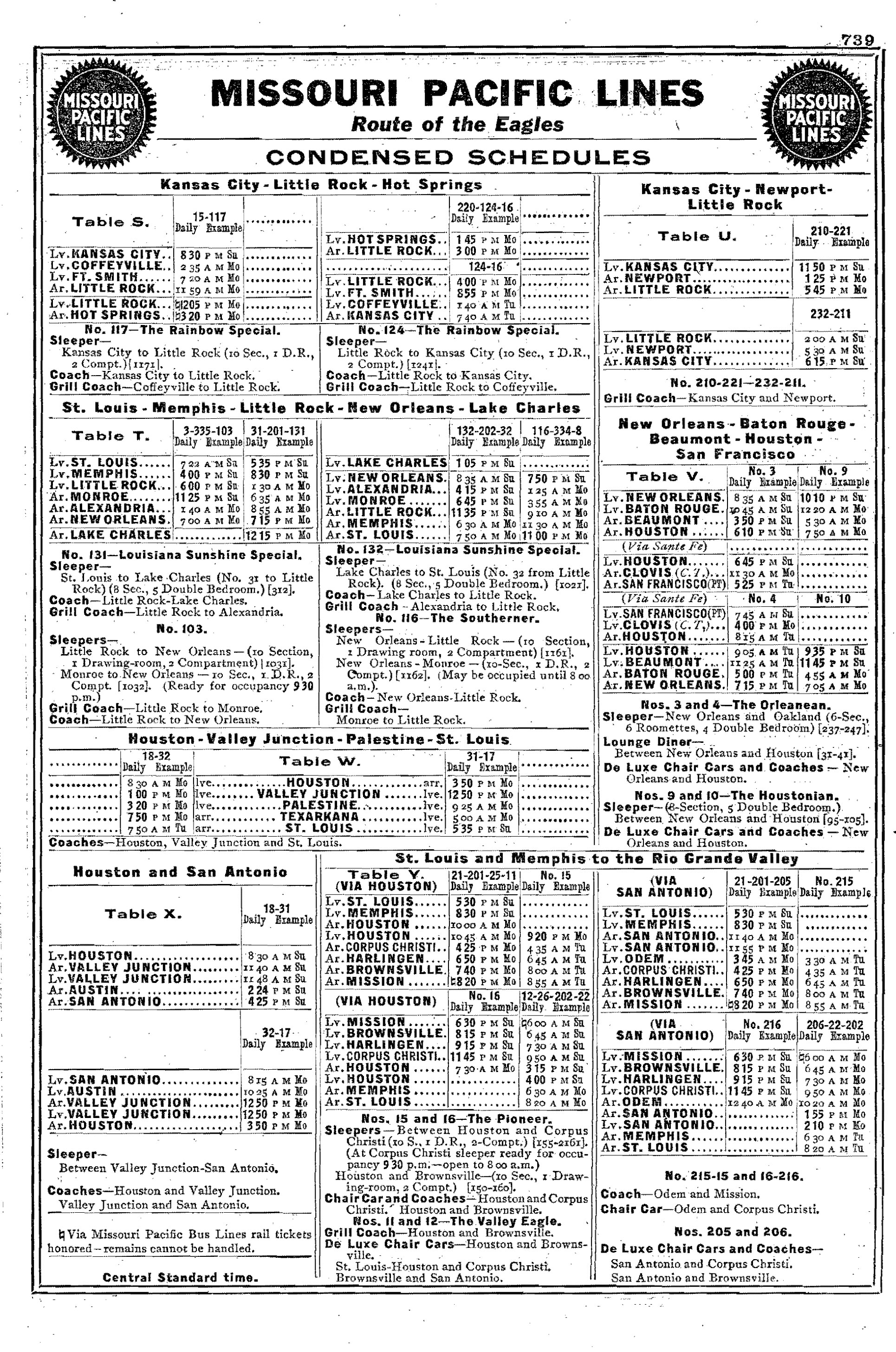

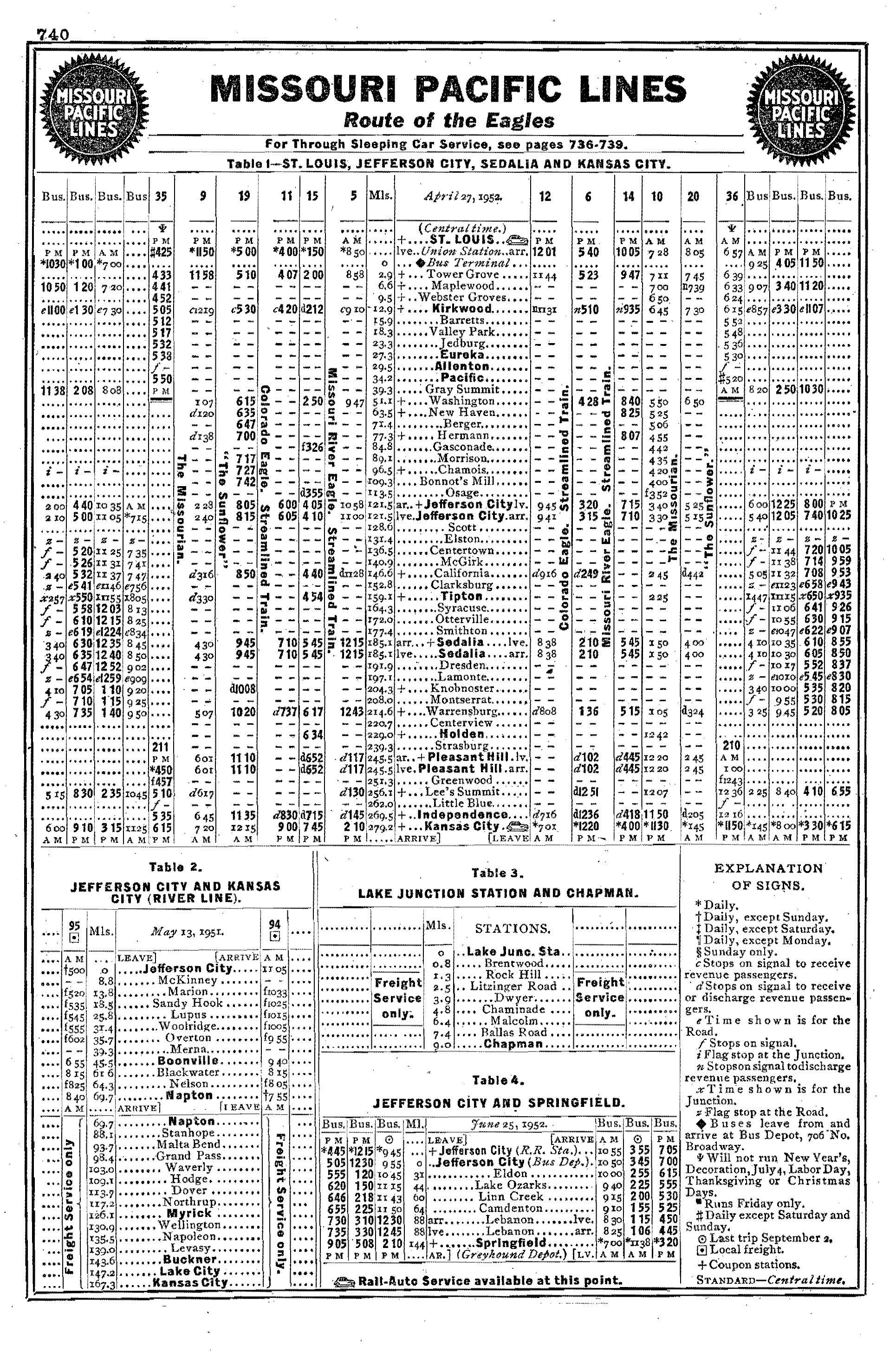

The MoPac’s fleet of passenger trains are well-remembered. It operated a number of popular services but is best known for its fleet of Eagles; the Aztec Eagle, Colorado Eagle, Missouri River Eagle, Valley Eagle, Louisiana Eagle, and the renowned Texas Eagle. These trains, and others, reached far and wide across its vast network.

Unfortunately, most perks and comforts were removed by the 1960's as the public abandoned railroads were automobiles and airlines. When Downing Jenks achieved the presidency he immediately took steps to eliminate this money-losing venture, which by 1962 amounted to more than $12 million annually.

However, the process was slow. Despite paltry and insignificant patronage, the public and state/government officials fought discontinuance, largely out of nostalgia. This issue was problematic industry-wide, resulting in many trains running far longer than they should have.

By 1969 only two MoPac trains, one of which was the famed Texas Eagle. It made its last run during September of 1970, carrying just seventeen passengers as part of a two-car consist. Interestingly the Eagle name did not disappear after passenger services ended. The company continued to use it in marketing high-speed freight services.

Aztec Eagle: (San Antonio - Mexico City)

Colorado Eagle: (St. Louis - Pueblo - Denver)

Houstonian: (New Orleans - Houston)

Louisiana Sunshine Special: (Little Rock - Lake Charles)

Missouri River Eagle: (St. Louis - Omaha)

Missourian: (St. Louis - Kansas City/Wichita)

Orleanean: (Houston - New Orleans)

Ozarker: (St. Louis - Little Rock)

Pioneer: (Houston - Brownsville)

Rainbow Special: (Kansas City - Little Rock)

Royal Gorge: (Kansas City - Pueblo)

Southerner: (St. Louis - El Paso/San Antonio/New Orleans)

Southern Scenic: (Kansas City - Memphis)

Sunflower: (St. Louis - Kansas City/Wichita)

Sunshine Special: (St. Louis - Hot Springs/San Antonio)

Texan: (St. Louis - Fort Worth)

Texas Eagle: (St. Louis - El Paso/San Antonio/Palestine/Galveston)

Valley Eagle: (Houston - Brownsville)

During MoPac's final years its traffic-base was widely diversified ranging from coal, agriculture, and manufacturing to trailer-on-flat-car (TOFC), ore, and automobiles.

In 1967 it gained stock control of the Chicago & Eastern Illinois, which provided a coveted entry into Chicago. Another corporate change took place a few years later when, on October 15, 1976, it formally dissolved the C&EI and T&P, giving it a total network of roughly 12,000 route miles.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3-4, 9007-9008, 9013-9015 | 1940-1947 | 7 |

| S2 | 11-14, 9107-9116, 9128-9132 | 1941-1949 | 19 |

| RS2 | 21-23, 61 | 1948-1949 | 4 |

| RS3 | 19-20, 24, 62-74, 4501-4526 | 1951-1955 | 42 |

| FA-1 | 301-330 | 1948-1950 | 30 |

| FB-1 | 301B-310B, 321B-325B | 1948-1950 | 15 |

| FA-2 | 331-360, 374-386 | 1951-1954 | 43 |

| FB-2 | 331B-356B, 370B-386B | 1951-1954 | 33 |

| FPA-2 | 361-373, 387-392 | 1952-1954 | 18 |

| RS11 | 4601-4612 | 1959 | 12 |

| PA-1 | 8001-8008 | 1949 | 8 |

| PA-2 | 8009-8036 | 1950-1952 | 28 |

| HH-1000 | 9102 | 1939 | 1 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DR-4-4-1500 (Babyface) | 201A-208A | 1948 | 8 |

| DR-4-4-1500 (B) | 201B-204B | 1948 | 4 |

| DRS-4-4-1500 | 4112-4115 | 1949 | 4 |

| AS16 | 4195-4196, 4326-4331 | 1951-1954 | 8 |

| VO-660 | 9009-9010, 9012, 9022, 9090-9091, 9206 | 1940-1941 | 7 |

| VO-1000 | 9103, 9117-9119, 9150-9155, 9160-9161, 9198-9199 | 1939-1949 | 14 |

| DS-4-4-1000 | 9120-9127, 9133-9141, 9148-9149, 9162-9167 | 1948-1950 | 25 |

| S12 | 9200-9239 | 1951-1953 | 40 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP18 | 400-499, 534-550, 1145-1149, 4801-4829 | 1960-1963 | 151 |

| FTA | 501-512 | 1943-1945 | 12 |

| FTB | 501B-512B | 1943-1945 | 12 |

| F3A | 513-571, 576 | 1947-1948 | 60 |

| F3B | 513B-518B, 525B-526B, 553B-556B, 561B-570B | 1947-1948 | 22 |

| GP38 | 572-577 | 1966-1967 | 6 |

| F7A | 577-626, 1500-1582 | 1949-1951 | 133 |

| F7B | 587B-596B, 629B-630B, 1500B-1534B | 1949-1951 | 47 |

| GP35 | 600-649 | 1963-1965 | 50 |

| SD40 | 700-789 | 1967-1971 | 90 |

| SD40-2 | 790-814, 816-839, 3139-3321, 6020-6073 | 1973-1980 | 286 |

| SW8 | 811-818 | 1952 | 8 |

| GP38-2 | 858-959, 2111-2237, 2290-2334 | 1972-1981 | 274 |

| NW2 | 1000-1019, 9104-9106 | 1939-1949 | 23 |

| SW7 | 1020-1023, 9142-9146 | 1950 | 9 |

| SW9 | 1024-1036, 9170-9191 | 1951 | 35 |

| SW1200 | 1100-1166, 1175-1201, 1255-1259, 1263-1279, 1280-1289 | 1963-1966 | 126 |

| GP7 | 1110-1130, 4116-4194, 4197-4325 | 1950-1954 | 229 |

| GP9 | 1131-1144, 4332-4371 | 1955-1959 | 54 |

| MP15DC | 1356-1392, 1530-1554 | 1974-1975 | 62 |

| SW1500 | 1518-1521 | 1972 | 4 |

| GP15-1 | 1555-1714 | 1976-1982 | 160 |

| GP15AC-1 | 1715-1744 | 1982 | 30 |

| E7A | 2000-2009, 7004-7017 | 1947-1948 | 24 |

| E8A | 2010-2017, 7018-7021 | 1950-1951 | 12 |

| GP50 | 3500-3529 | 1980-1981 | 30 |

| NC | 4100-4101 | 1937 | 2 |

| NW4 | 4102-4103 | 1938 | 2 |

| BL2 | 4104-4111 | 1948 | 8 |

| E3A | 7001 | 1939 | 1 |

| E6A | 7002-7003 | 1941 | 2 |

| E6B | 7002B-7003B | 1941 | 2 |

| E7B | 7004B, 7010B-7012B, 7014B-7017B | 1945-1948 | 8 |

| SC | 9000-9003 | 1937 | 4 |

| SW1 | 9004-9006, 9011, 9200-9205 | 1939-1941 | 10 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U30C | 25-29, 960-983, 3329-3334 | 1968-1973 | 35 |

| U23B | 668-674, 2257-2288 | 1973-1977 | 39 |

| 44-Tonner | 800-801, 811-815 | 1941-1942 | 7 |

| B23-7 | 2289-2358, 4670-4684 | 1978-1981 | 85 |

| B30-7A | 4800-4854 | 1982 | 55 |

| C36-7 | 9000-9059 | 1985 | 60 |

Steam Rosters

Missouri Pacific

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| 6, 12, 2208, 2502, 8510, 8552, 8562, 8601, E (Various) | American | 4-4-0 |

| 801, 851, C (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| 1699, M (Various), MK (Various) | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| 2101, 26S-63 | Northern | 4-8-4 |

| 6000, 6001, P (Various) | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| A (Various) | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| BK (Various) | Berkshire | 2-8-4 |

| L-1, SF-63 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| MT (Various) | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| TW (Various) | Twelve-Wheeler | 4-8-0 |

Texas & Pacific

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A-2 Through A-4 | American | 4-4-0 |

| B-1 Through B-8 | Switcher | 0-6-0/T |

| BK-63 | Berkshire | 2-8-4 |

| C-1 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| C-2/a | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| D-1 Through D-11-S | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| E-1 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| F-1, F-1-S | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| H-1, H-2 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| I-1 | Texas | 2-10-4 |

| E-1 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| M-1, M-2 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| P-1 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| 2100/26S-63 | Northern (Rebuilt from its fleet of Bekshires.) | 4-8-4 |

Missouri Pacific E8A #40 (built as #7020), circa 1968. Location not listed. American-Rails.com collection.

Missouri Pacific E8A #40 (built as #7020), circa 1968. Location not listed. American-Rails.com collection.As the industry struggled through the 1970's the merger movement gained evermore momentum. The process had been ongoing since the late 1950's as executives sought to cut red ink. However, it really took off following several bankruptcies and the Staggers Act's passage in 1980.

This piece of legislation greatly deregulated the industry, enabling railroads an easier process of merging and abandoning unprofitable lines.

During that decade the already very-large Burlington Northern system (formed in 1970) added the St. Louis-San Francisco, Santa Fe and Southern Pacific attempted their own marriage, and Union Pacific was eyeing the Western Pacific.

Union Pacific Acquisition

With Jenks still calling the shots, it was obvious the MoPac needed to find its own partner to ensure long-term survival. As a result, a plan to join the UP/WP merger was worked out by all three railroads in 1980 (MP shareholders approved the deal on April 18th).

Two years later, on September 13, 1982 the Interstate Commerce Commission also gave its blessing and a much larger Union Pacific was born. Interestingly, as Mike Schafer notes in his book, "More Classic American Railroads," when the merger occurred MP actually carried more locomotives route mileage than UP.

During is last years of service the MoPac was a fine operation; in 1979 it had a net income of $32.6 million and gross revenues of over $524 million.

Today, Amtrak continues to operate its Texas Eagle and Union Pacific paid homage to the railroad in 2005 by painting one of its new EMD SD70ACe locomotives into a version of its famous blue and gray passenger livery complete with an eagle adorning the locomotive’s nose.

The unit debuted during the summer of 2005 and received a number recognizing Missouri Pacific’s final year of independence, 1982.

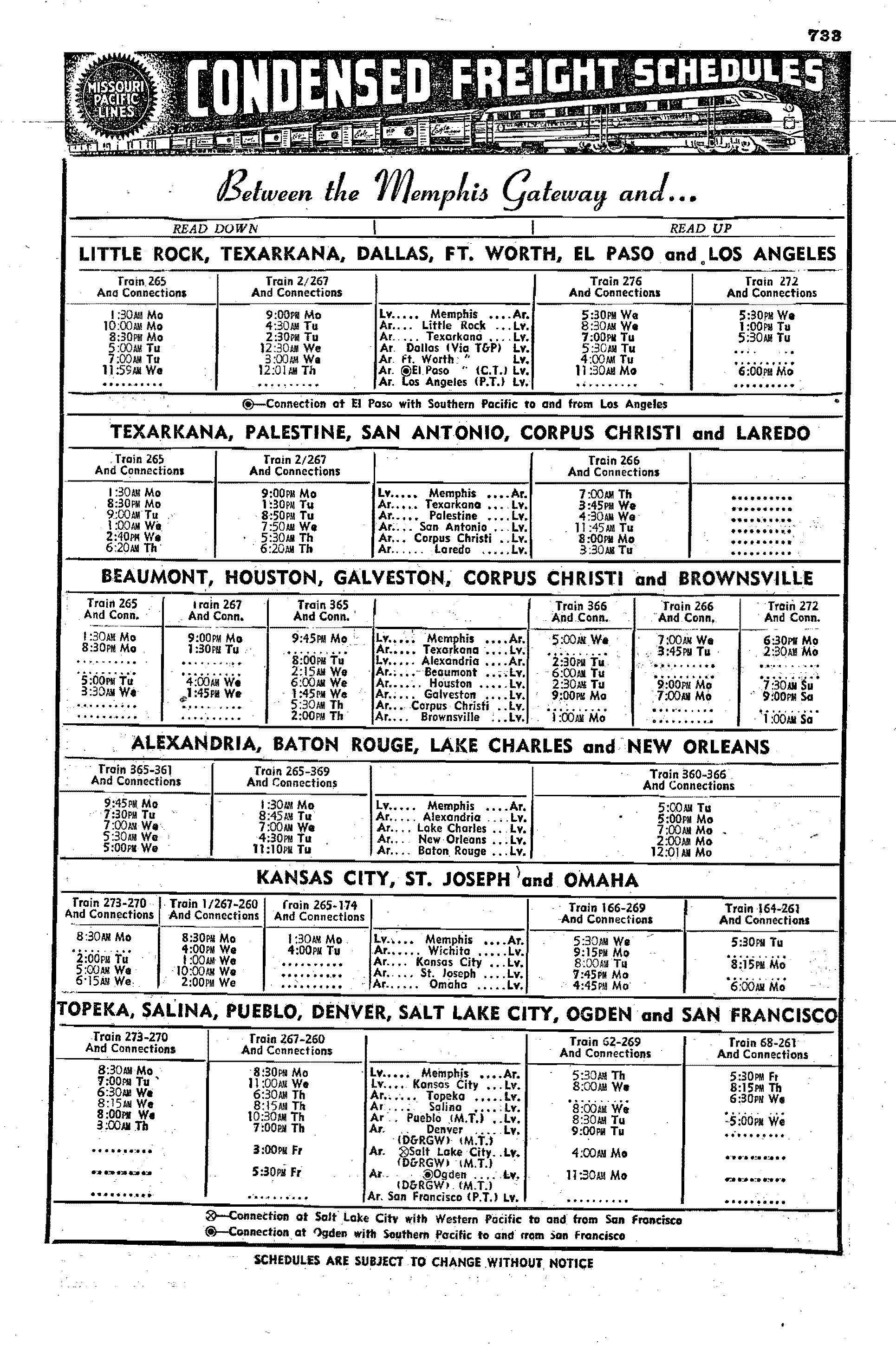

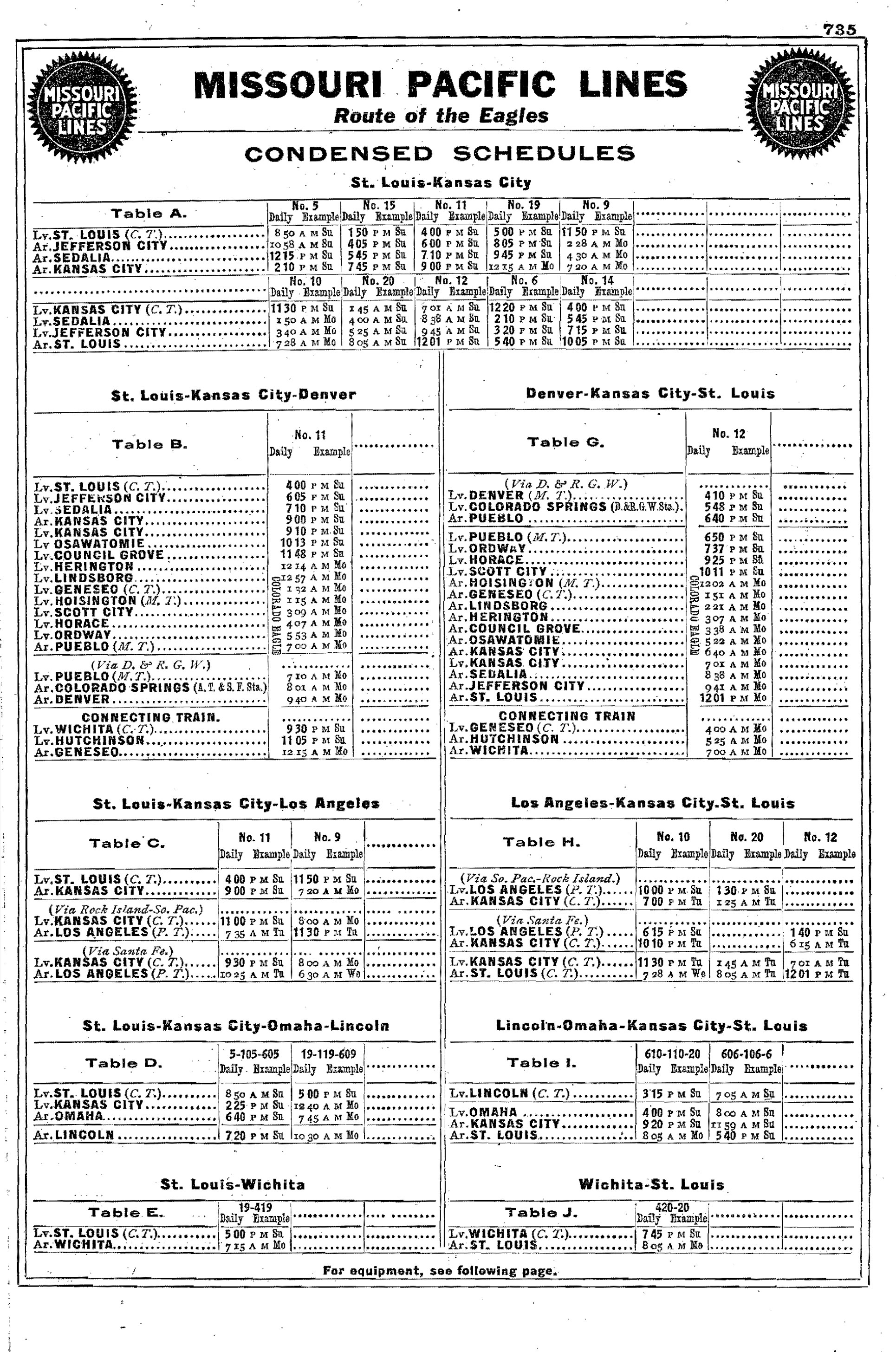

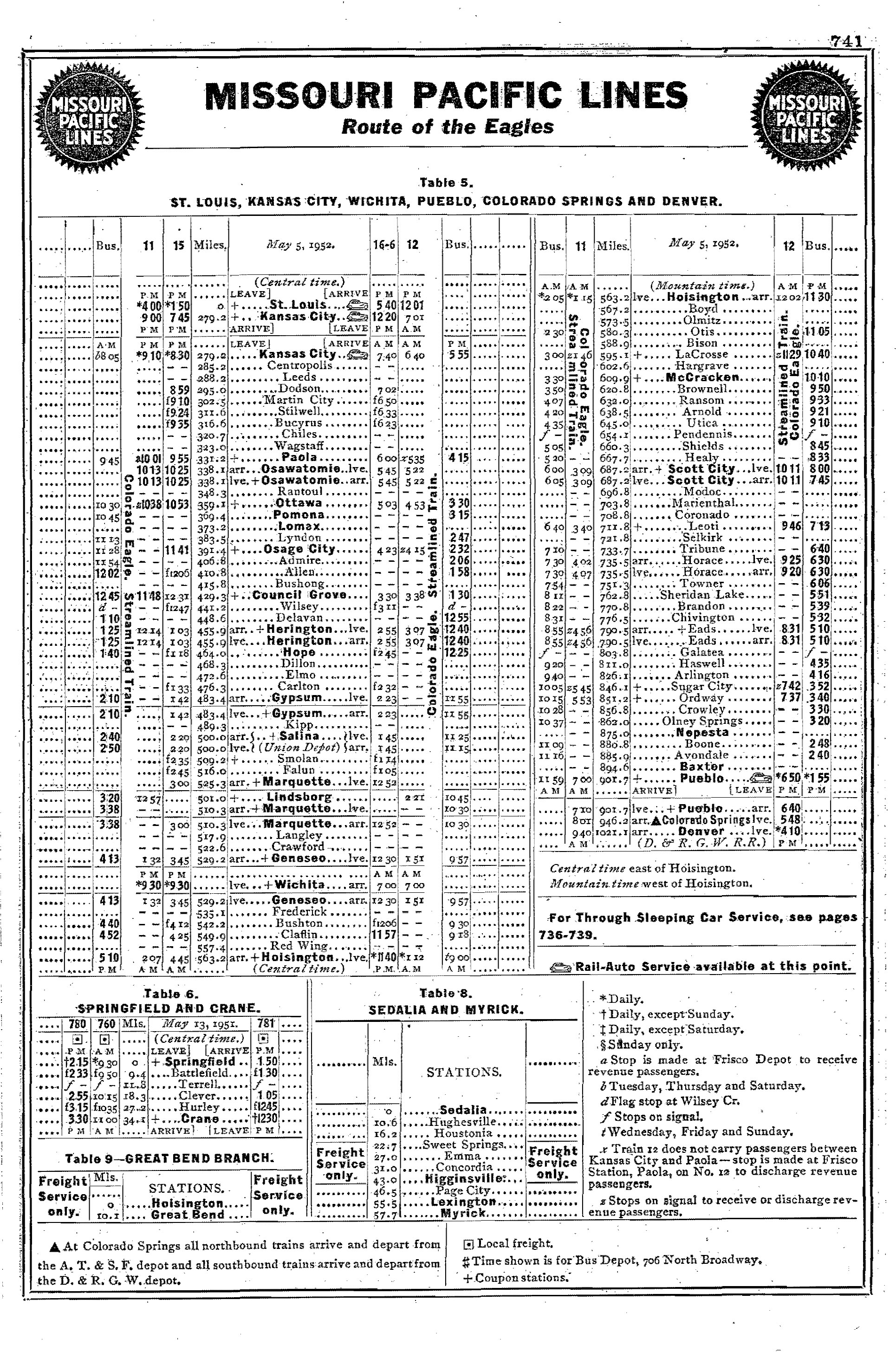

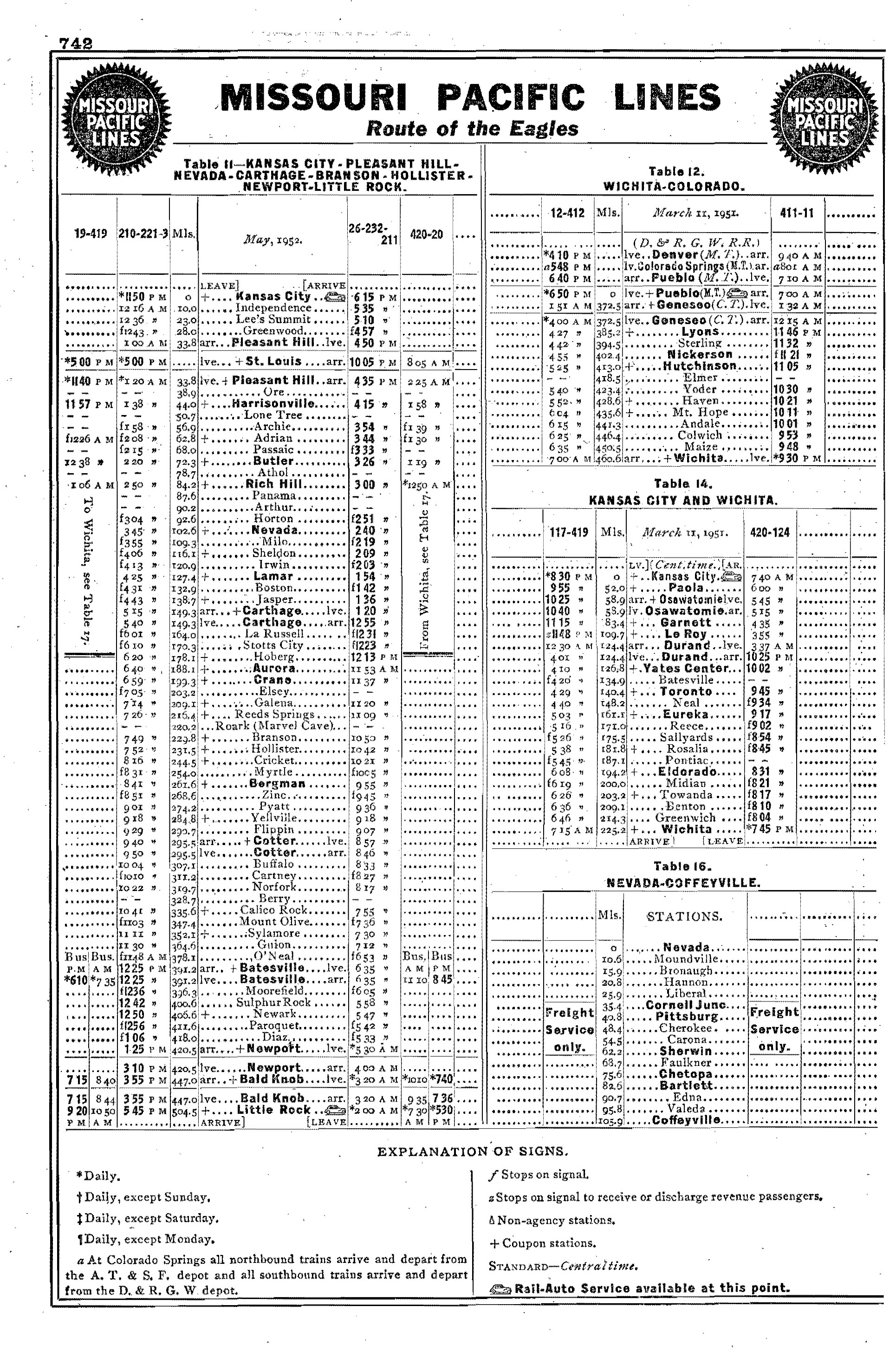

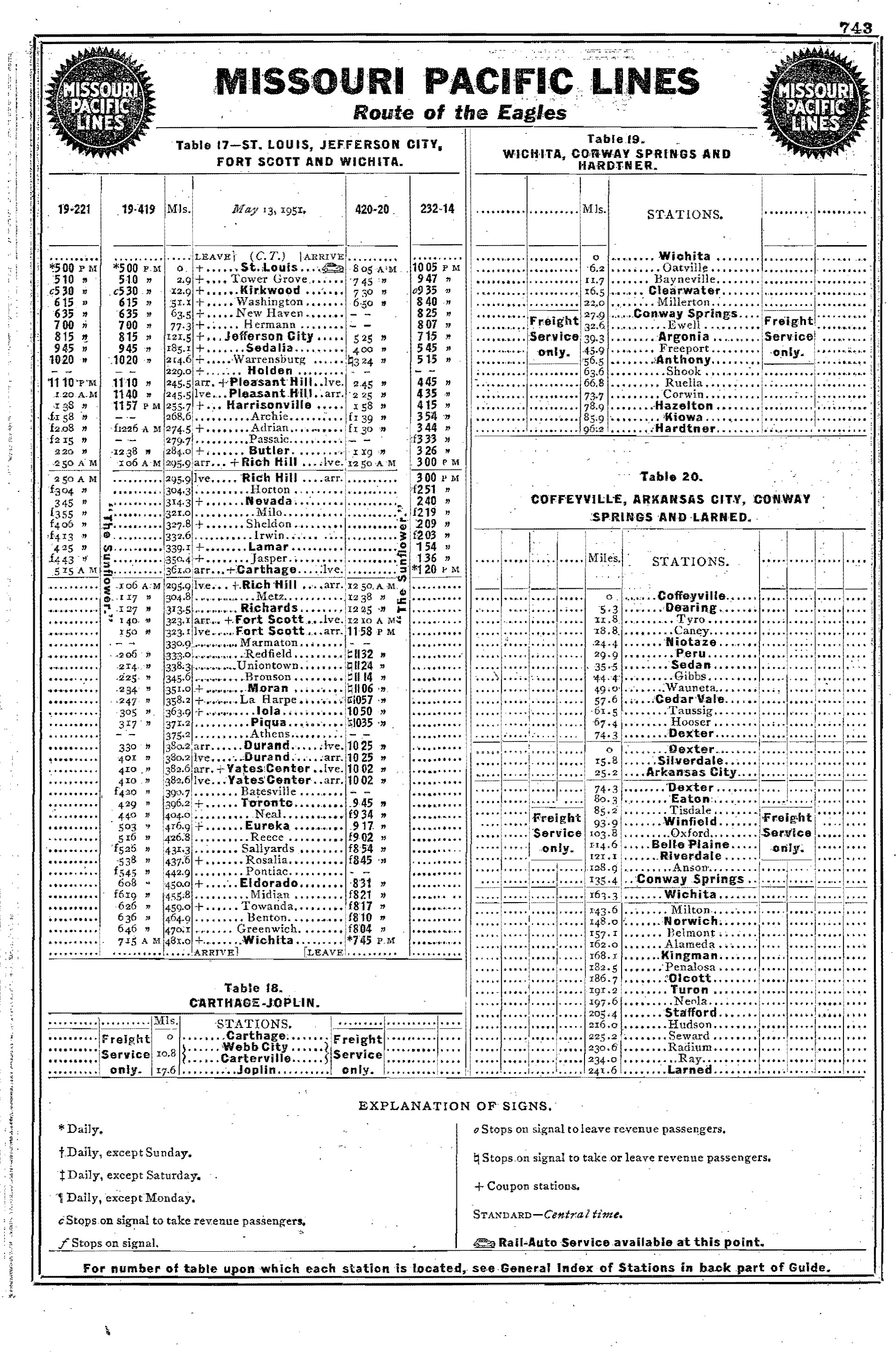

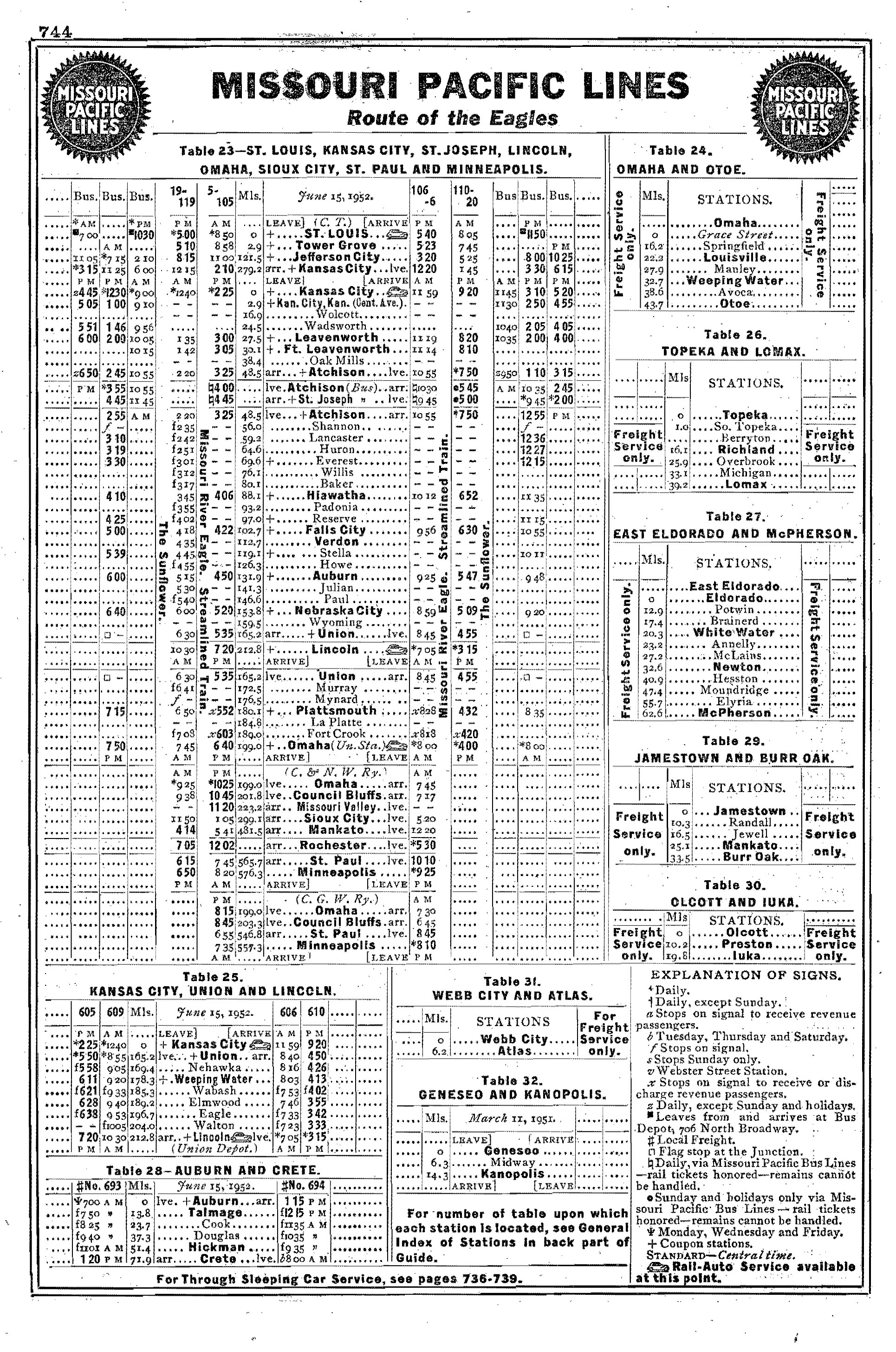

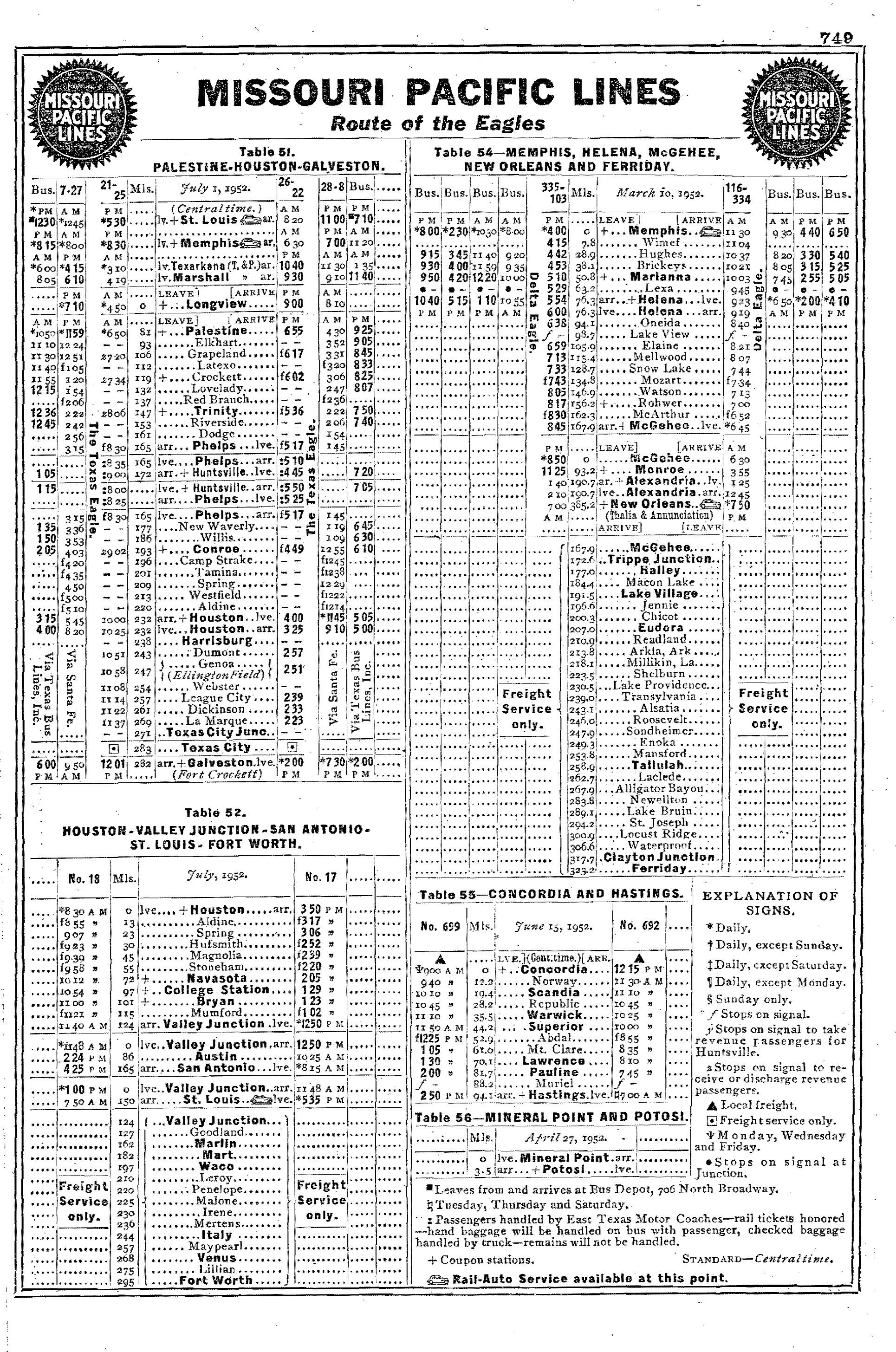

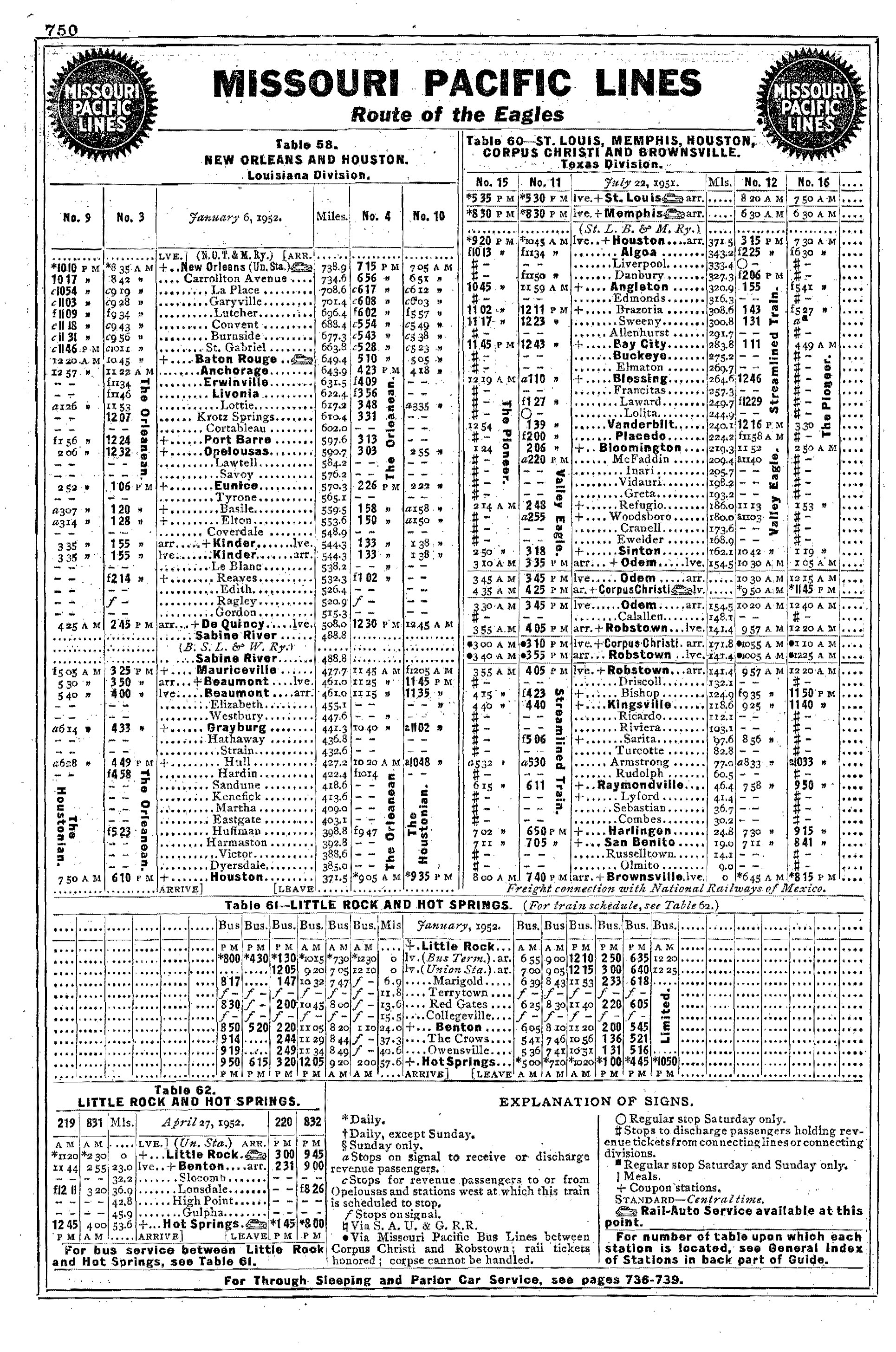

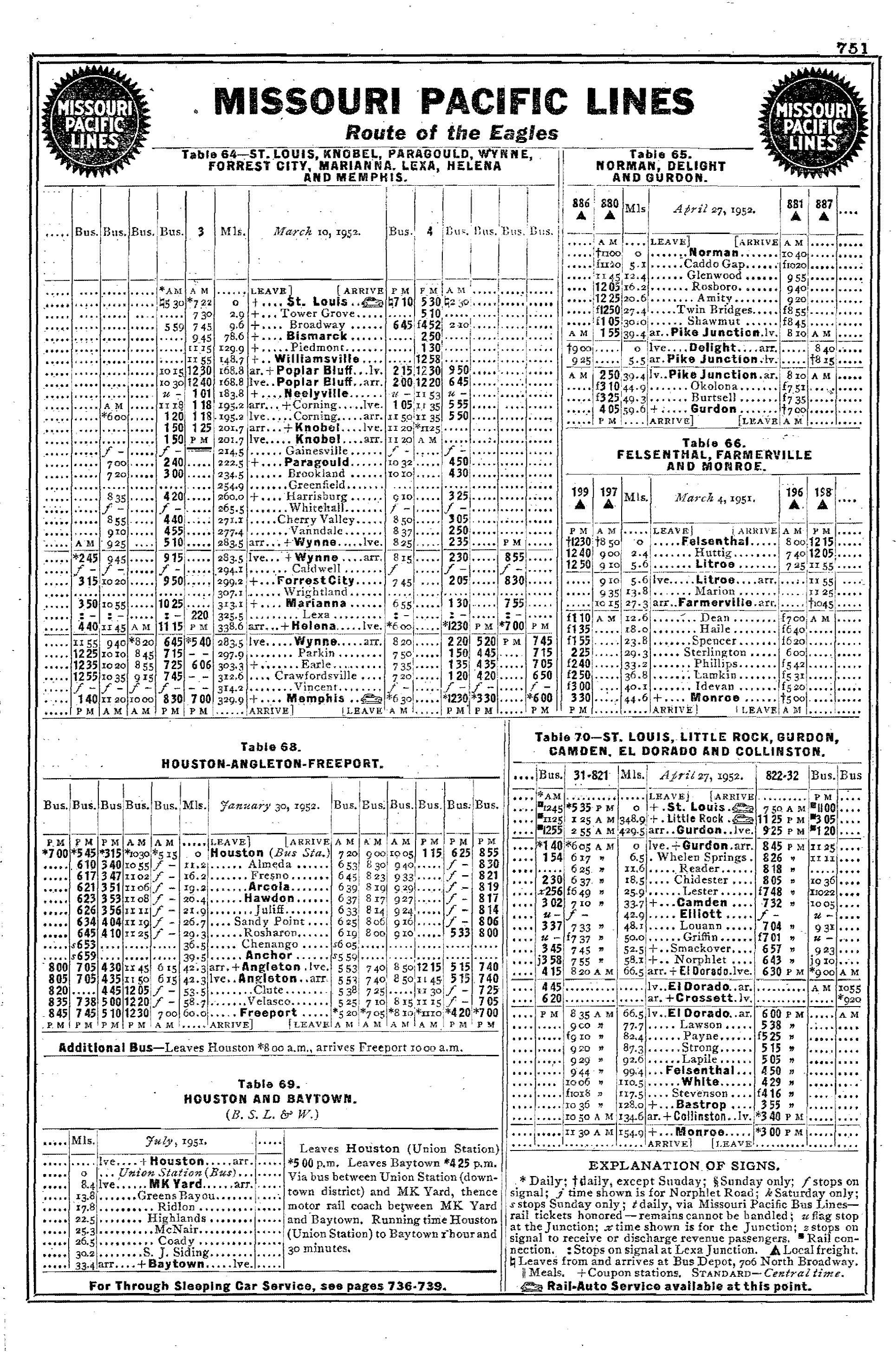

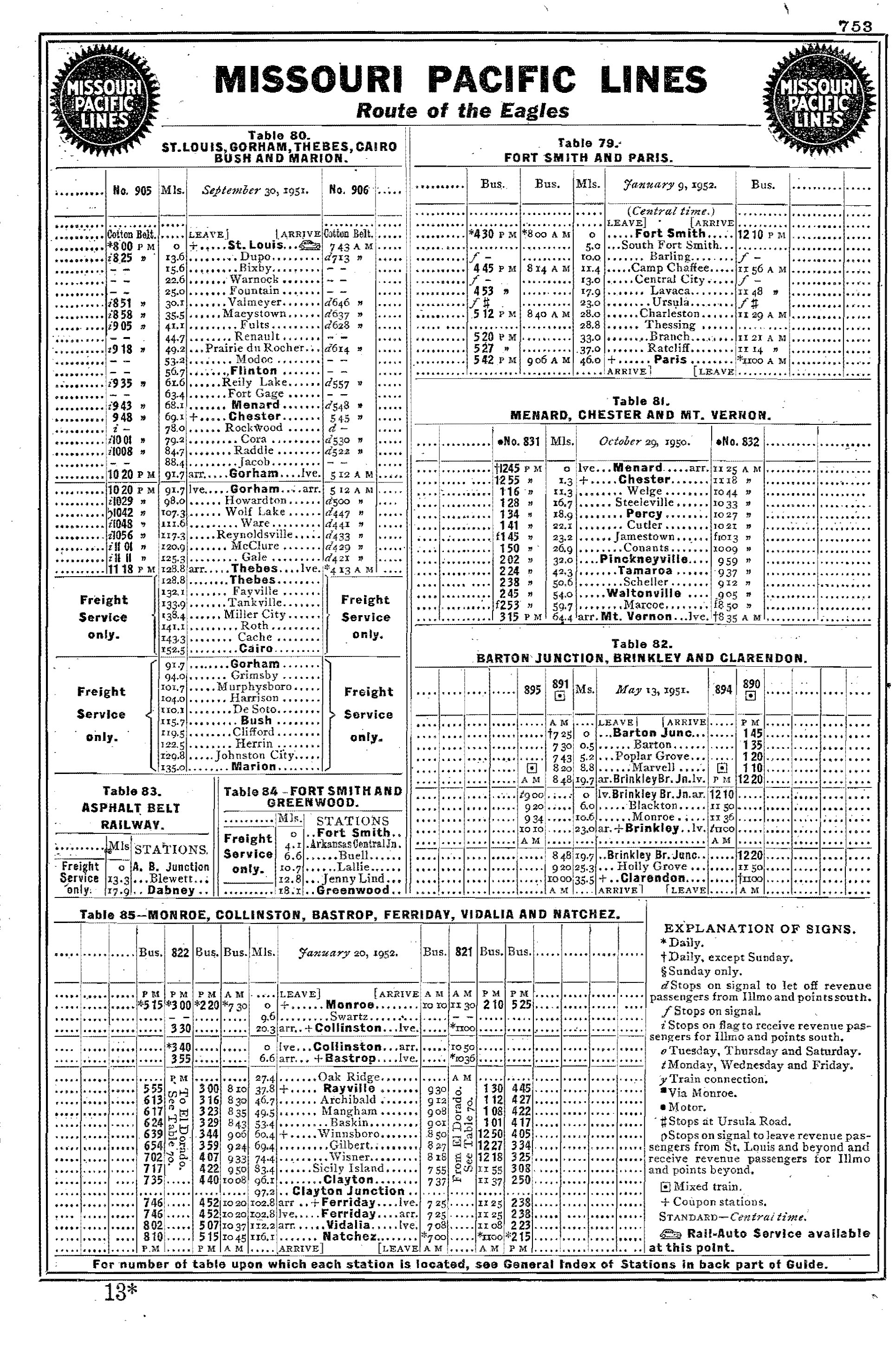

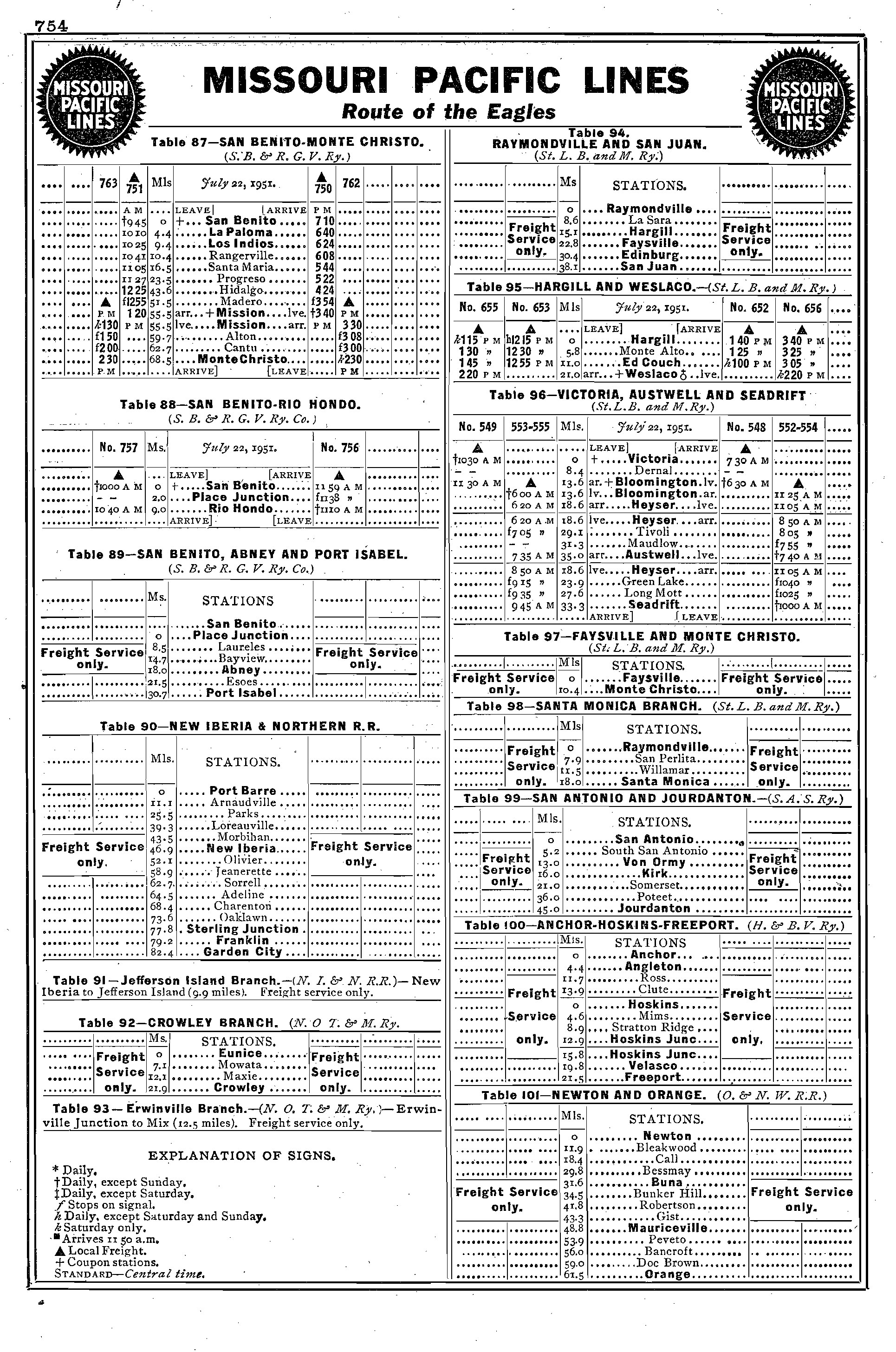

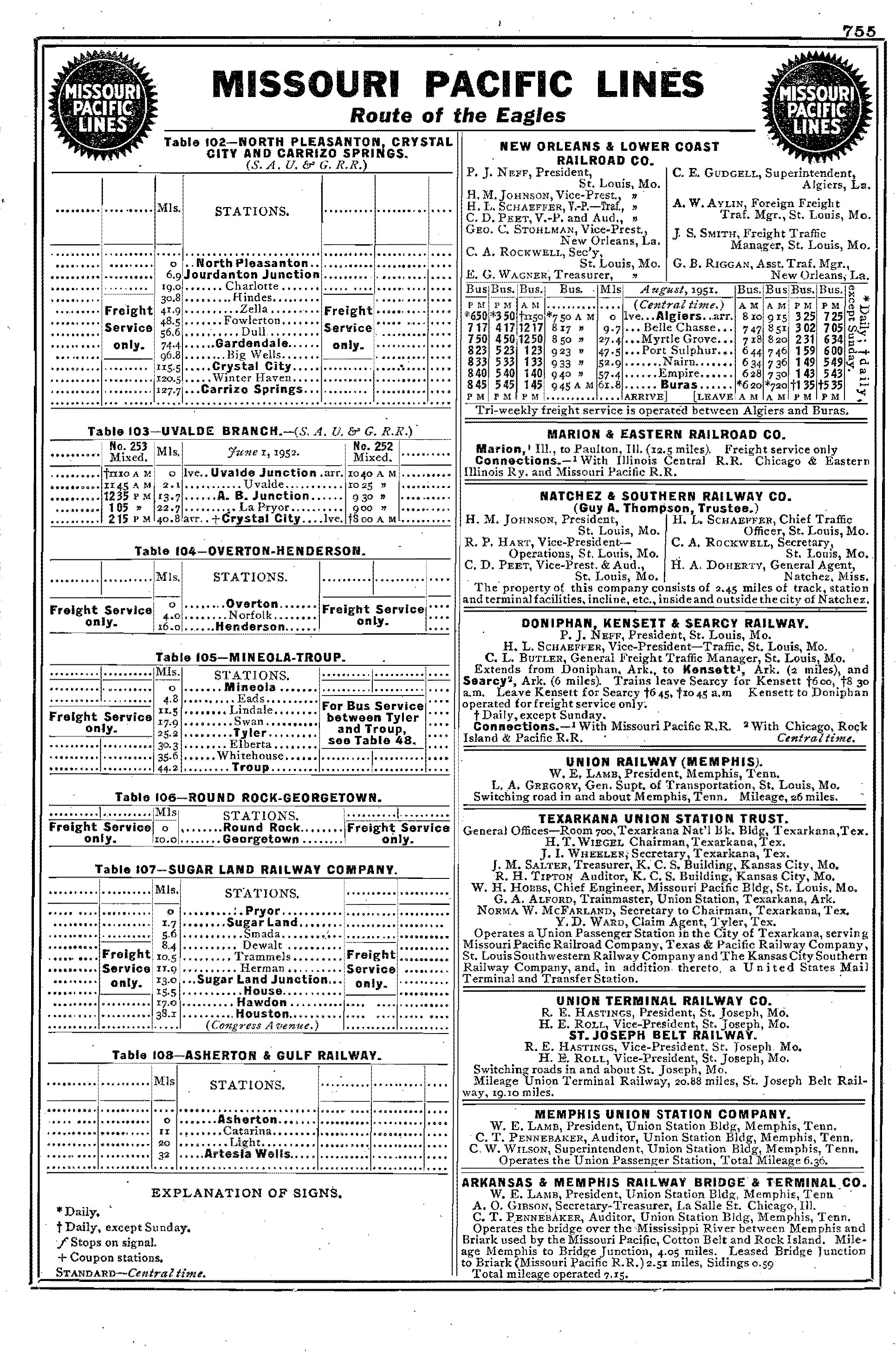

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

The Raleigh-to-Richmond 'S' Line: Rebuilding A Vital Corridor

Jan 18, 25 08:21 PM

The 'S' Line project intends to reconnect Raleigh to Richmond by rail via the Seaboard Air Line's former main line abandoned under CSX during the 1980s. -

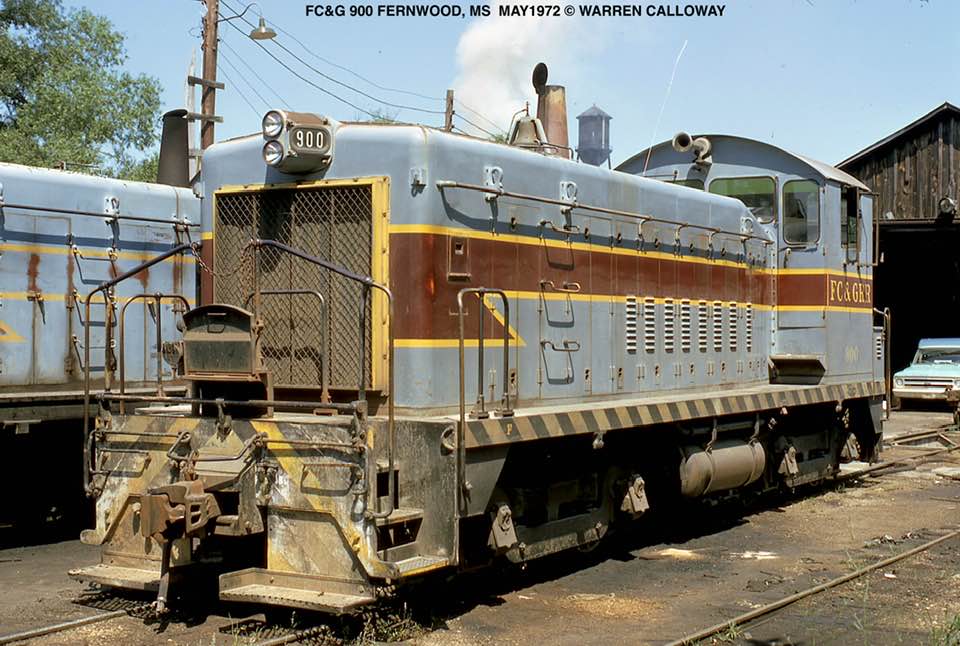

Fernwood, Columbia & Gulf Railroad: "The Pine Leaf Route"

Jan 17, 25 11:38 PM

A division of the Fernwood Lumber Company, the Fernwood, Columbia & Gulf Railroad was formed in 1920 to handle lumber traffic. It was acquired by the ICG in 1972 and later abandoned. -

The "NW3": Intended For Terminal Assignments

Jan 17, 25 11:20 PM

The NW3 was an early experimental road-switcher design marketed by Electro-Motive to offer a steam-generator equipped light-road switcher for passenger terminal assignments. Ultimately, just 7 were pr…