- Home ›

- Streamliners ›

- Mercury

The "Mercury" (Train) Of 1936: Interior, Top Speed, History

Last revised: September 15, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The New York Central made its splash into the streamliner craze shortly after the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy's (Burlington) Pioneer Zephyr and Union Pacific's M-10000 dazzled onlookers in early 1934.

Dubbed the Mercury, this eye-catching train was not exactly a new concept. Instead, it was built from scratch using older, heavyweight cars and locomotives already in service.

During the post-depression era, the New York Central remained hesitant to spend millions on a style that was still under development and unproven.

However, the railroad was not entirely conservative. To give the Mercury its own flavor and character, noted industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss was the hired. The train proved a great success with the public, stunning spectators.

The New York Central was so pleased with the results it would go on to field an entire fleet of streamliners with names like the:

- 20th Century Limited

- Commodore Vanderbilt

- Empire State Express

- James Whitcomb Riley

- Knickerbocker

- Lake Shore Limited

- New England States

- Pacemaker

- Wolverine

The original Mercury eventually dubbed the Cleveland Mercury and remained in service until the 1950s.

Photos

This New York Central publicity photo was taken on June 28, 1936 beneath Grand Central Terminal. It was all part of a PR tour following the train's completion at NYC's Beech Grove Shops in Indianapolis. Featured here is 4-6-2 #4915 (K-5a) leading the seven car consist. It was originally built in 1926 and received its Henry Dreyfuss-designed streamlining at NYC's West Albany Shops. Patty Allison colorized photo.

This New York Central publicity photo was taken on June 28, 1936 beneath Grand Central Terminal. It was all part of a PR tour following the train's completion at NYC's Beech Grove Shops in Indianapolis. Featured here is 4-6-2 #4915 (K-5a) leading the seven car consist. It was originally built in 1926 and received its Henry Dreyfuss-designed streamlining at NYC's West Albany Shops. Patty Allison colorized photo.History

As the Union Pacific kicked off the streamliner craze in February, 1934 with its M-10000 trainset (honored as the very first ever-introduced), followed by the Burlington's incredibly popular Pioneer Zephyr (the first utilizing a diesel engine), other railroads soon realized the invaluable publicity such trains offered.

During a time when business was down as a result of the ongoing economic struggles, anything to attract folks back to the rails was eagerly implemented.

At A Glance

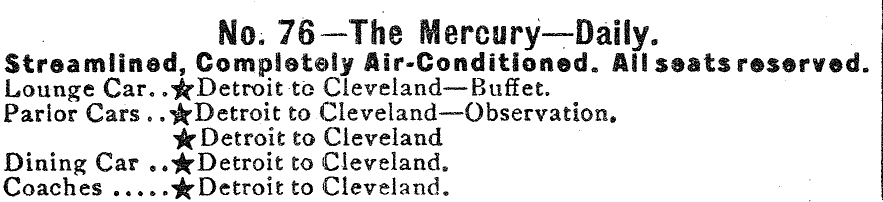

750/75 (westbound) 761/76 (eastbound) | |

Michigan Central Station (Detroit) Union Station (Cleveland) |

|

Many companies were struggling mightily and several would find themselves in bankruptcy prior to 1940. For those strong enough to spend resources on either building or buying streamliners the benefits were immediate and glaring.

In addition, companies which launched them prior to World War II's onset enjoyed the benefit of running these trains during the war years. For the New York Central it too wanted in on the excitement but management was quite frugal, and rightly so, given the times.

Instead, the company went searching for its own design. What it came up with was an entirely "new" streamliner utilizing dated, heavyweight equipment which the railroad scrounged from around its network (these cars turned out to be aging commuter coaches built during the 1920's).

Drumhead

This was not exactly a novel idea, even for that time; one of NYC's competitors, the venerable Baltimore & Ohio, had recently done something quite similar when it overhauled its Royal Blue in a similar fashion (this was B&O's preeminent service between Washington, D.C. and New York City).

Consist (1940)

Interior and Accommodations

The NYC's new train was envisioned as a seven-car consist and the railroad quickly went to work overhauling the cars. While they were not rebuilt from the ground up, considerable overhauling was carried out, all accomplished at the company's shops in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The interior was the work of Henry Dreyfuss, an industrial design who applied his self-described "cleanlining" approach to transform the cars into elegant works of art.

4-6-2 Engine

After he had finished the train carried a similar look the legendary 20th Century Limited, designed and launched only a few years later.

The Mercury boasted a smooth, yet dignified look with pastels, carpeting, sealed windows, indirect lighting, and the new technology of air-conditioning (a quite common feature on many railroads' flagship services beginning in the 1930's). Of course, as expected, the train featured considerable Art Deco touches throughout.

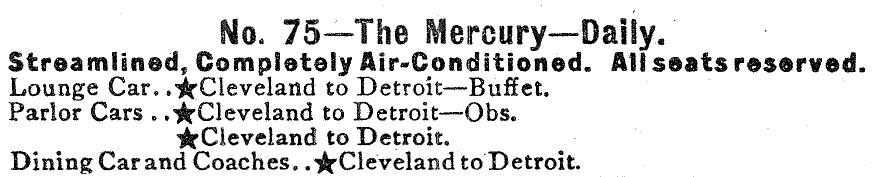

New York Central 4-6-2 #4915 leads the "Mercury" down Washington Street in Syracuse, New York, circa 1936.

New York Central 4-6-2 #4915 leads the "Mercury" down Washington Street in Syracuse, New York, circa 1936.Overall, the Mercury's seven-car layout included a parlor, coaches, diner, lounge, and observation car (with wide windows and a round-ended design it gave the train a very nice "finished" appearance). From an exterior standpoint it also closely resembled the 20th Century Limited with its two-tone gray livery.

For power the NYC chose one of its "K Class" 4-6-2, already in service (another way officials kept costs low). However, this was no ordinary steam locomotive, thanks to the work done by shop forces in Albany, New York. This "Pacific Type" steamer was completely shrouded, giving it a streamlined appearance.

Route Map (1938)

1936 Debut

Also the work of Dreyfuss, he elected to leave the wheels and driving rods exposed allowing the public

to see the mighty machine hard at work. Finally, in one of the most

innovative ideas ever applied to a steam locomotive, Dreyfuss also added lighting to the wheels enabling everyone to

see them in motion at night!

The train hit the rails on June 25, 1936 and the public was immediately amazed and awed. Over the next few months it traveled around NYC's network before entering regular service between Cleveland and Detroit on July 15, 1936.

Timetable (August, 1938)

| Read Down Time/Leave (Train #761) | Milepost | Location | Read Up Time/Arrive (Train #750) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:30 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 10:30 AM (Ar) | |

| 6:30 PM (Ar) | 58 | 9:25 AM (Dp) | |

| Time/Leave (Train #76) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #75) |

| 6:30 PM (Dp) | 58 | 9:25 AM (Ar) | |

| 8:20 PM (Ar) | 164.6 | 7:45 AM (Dp) |

New York Central's all-new "Mercury" on display at Toledo Union Station on July 2, 1936. George Blount photo.

New York Central's all-new "Mercury" on display at Toledo Union Station on July 2, 1936. George Blount photo.Final Years

The corridor was 164 miles in length and the Mercury could complete the trip in about 2 hours, 50 minutes with one stopover in Toledo. Just as other lines had experienced, demand for the train was so great new cars were soon added.

Additionally, in a spin-off was later introduced between Detroit and Chicago, the Chicago Mercury. The railroad continued to run the original consist until the aging equipment was finally pulled from service in the mid-1950s.

In the end, the New York Central fell in love with the streamliner. Its frugal was would later give way to millions spent on new cars and locomotives from Pullman-Standard and Electro-Motive.

As Mike Schafer and Joe Welsh note in their book, "Streamliners: History Of A Railroad Icon," the NYC would spend an astonishing $90 million during, and immediately after, World War II to reequip its fleet.

This figure provided it a total of 720 new cars from Pullman-Standard ("The World's Greatest Hotel"), Budd Company, and American Car & Foundry.

Sources

- Doughty, Geoffrey H. New York Central's Great Steel Fleet, 1948-1967 (Revised Edition). Lynchburg: TLC Publishing, Inc., 1999.

- Johnston, Bob and Welsh, Joe. Art Of The Streamliner, The. New York: Andover Junction Publications, 2001.

- Schafer, Mike and Welsh, Joe. Streamliners, History of a Railroad Icon. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2003.

- Solomon, Brian and Schafer, Mike. New York Central Railroad. St. Paul: Andover Junction Publications, 2007.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Massachusetts Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 11:41 PM

There are a handful of museums located in the state of Massachusetts detailing its long and storied history with trains, which can be traced back to the industry's earliest days. -

Maryland Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 01:36 PM

The state of Maryland is where it all began with the Baltimore & Ohio. Along with the B&O Railroad Museum, several other similar organizations can be found in the state. -

Maine Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 12:58 PM

Maine's railroads have long been associated with logging and agriculture. Today, a number of museums honoring this heritage can be found throughout the state.