Western Maryland Railway: Map, Rosters, Logo, History

Last revised: November 1, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Western Maryland Railway, affectionately known as the Wild Mary,

was a truly fascinating carrier; condensed within a network of just 800+ miles one could witness time freights, slow coal drags, backwoods locals, and even Shay geared locomotives!

The railroad was built through rough, but gorgeous, topography operating a main line featuring numerous tunnels and bridges.

While aspects of the system posed operational difficulties (notably Black Fork Grade), the WM offered some of the most fantastic photographic opportunities one could ever hope for as it navigated through the Appalachians of central/eastern West Virginia, parts of Maryland, and southwestern Pennsylvania.

After the railroad became part of Chessie System large segments were abandoned during the 1970s and 1980s. To put it bluntly, what a magnificent scenic railroad the entire WM would have offered (particularly through the Mountain State's Blackwater Canyon) if still intact today.

Its territory would easily rival anything offered from popular operations such as Strasburg, the Durango & Silverton Narrow-Gauge, and Grand Canyon Railway.

Photos

A handsome new Western Maryland F7A and other F7's lead a long freight through Hagerstown, Maryland in December, 1952. Aubrey Bodine photo

A handsome new Western Maryland F7A and other F7's lead a long freight through Hagerstown, Maryland in December, 1952. Aubrey Bodine photoHistory

The state of Maryland carried a forward-thinking approach to the newfangled railroad. It was quick to adopt the technology, an English invention, by chartering the Baltimore & Ohio in February of 1827, our country's first common-carrier.

The B&O was established to help sustain the city of Baltimore as an important eastern port in the face of newly-built canals linking cities such as Philadelphia and New York.

When Western Maryland's earliest predecessor, the Baltimore, Carroll & Frederick Rail Road Company, was chartered by the Maryland General Assembly on May 27, 1852 the B&O was already completing its envisioned route to Wheeling, Virginia along the banks of the Ohio River.

That road quickly proved its worth, despite many starts and stops. The BC&F was designed as another transportation artery for Baltimore, handling freight related to the agricultural, mining, and quarry industries.

According to the book, "The Western Maryland Railway: Fireballs And Black Diamonds" by Roger Cook and Karl Zimmermann, the road's promoters initially planned it to link Baltimore with the Monocacy River near then-Virginia's northeastern border (today, West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle).

At A Glance

Baltimore - Hagerstown, Cumberland, Maryland Cumberland - Connellsville, Pennsylvania Cumberland - Elkins, West Virginia Glyndon, Maryland - York, Pennsylvania Highfield, Maryland - Gettysburg - Hanover - Porters, Pennsylvania Hagerstown, Maryland - Shippensburg, Pennsylvania Elkins - Durbin, West Virginia Elk River Junction - Bergoo - Webster Springs, West Virginia Elkins - Belington, West Virginia Elkins - Dailey, West Virginia | |

Expansion

It was not long before they decided upon a name change to better reflect the company's intentions. On March 21, 1853 it became the Western Maryland Rail Road Company with construction officially launched from Baltimore on July 11, 1857.

This initial section utilized a segment of a former Baltimore & Susquehanna branch completed in 1832 between Relay House and Owings Mills. It was acquired by the WM in 1857 and opened for service on August 11, 1859 (by October of 1873 WM had established its own line into downtown Baltimore at Fulton Station).

A pair of Western Maryland RS3's receive a bath at the wash rack in Elkins, West Virginia on August 27, 1958. Author's collection.

A pair of Western Maryland RS3's receive a bath at the wash rack in Elkins, West Virginia on August 27, 1958. Author's collection.By the end of the year rails were pushed a bit further to the northwest at Reisterstown but stalled beyond that point as money ran out. With financial backing from the city, rails reached Union Bridge during November of 1862 when the project was again halted due to the Civil War.

Things finally picked up once more in 1868 and opened to Hagerstown in August of 1872. A year later, during the fall of 1873, service to Williamsport established connections with the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.

In 1884 the WM opened more efficient interchanges here with the B&O and Shenandoah Valley Railroad (a later Norfolk & Western property).

Fireball Logo

During 1874 John Mifflin Hood was elected president of the WM. He transformed the railroad into an important regional line and oversaw its largest growth until the Gould interests acquired control at the turn of the century.

His first expansion occurred in October of 1881 when 33.6 miles of the Baltimore & Cumberland Valley Rail Road was leased between Edgemont, Maryland and Shippensburg, Pennsylvania via Chambersburg and Waynesboro.

This line proved a vital component of the later "Alphabet Route" high-speed freight corridor when the railroad completed a short branch at Shippensburg to the Harrisburg & Potomac, a future Reading Company property.

The flurry of acquisitions during the 1880s continued as Western Maryland added the Baltimore & Hanover and Gettysburg Rail Road systems in late 1886. These two lines opened connections to Gettysburg and Hanover via Emory Grove.

The WM consolidated them into the Baltimore & Harrisburg Railway that same year and completed extensions to the west at Highfield, Maryland in June of 1889 as well as northeasterly to York, Pennsylvania in 1893 (the latter offered interchanges with the Pennsylvania Railroad and short line Maryland & Pennsylvania). This line, the future Hanover Subdivision, was more commonly known as the "Dutch Line."

Passenger Trains

The Western Maryland maintained only modest passenger services and never bothered with the idea of streamlining. It did operate a few high-class accommodations for a handful of years following the opening of the Connellsville Extension.

In 1913 it entered into a contract with Pullman to operate sleepers as part of the westbound Chicago Limited (Baltimore - Chicago, Train #3) and eastbound Baltimore Limited (Chicago - Baltimore, Train #2), which terminated at Hillen Station in Baltimore (the WM's terminal there since 1876).

In addition, these trains ran with parlors, diners, and club cars. Their immediate subordinates were the less flashy Western Express (Train #7) and Eastern Express (Train #8).

All of these trains operated in conjunction with the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie (Connellsville - Youngstown), Erie (Youngstown - Cleveland), and New York Central (Cleveland - Chicago).

The Limiteds' running times were quite competitive at 21 1/2 to 22 1/2 hours but survived only until 1917 after which time WM maintained coach-only services.

Western Maryland 4-6-2 #206 works passenger service as it is serviced at Thurmont, Maryland, circa 1952. American-Rails.com collection.

Western Maryland 4-6-2 #206 works passenger service as it is serviced at Thurmont, Maryland, circa 1952. American-Rails.com collection.Nearly all of its trains were powered by a fleet Pacific's, either ten K-1's built in 1909 by Baldwin (#151-160) or the nine more powerful K-2's (#201-209) that arrived in 1912. For many years these locomotives handled nearly all passenger assignments.

However, beginning in the 1930s beefy little H-7b or H-8 Consolidations normally worked the Durbin Branch via a mixed train.

Surprisingly, this operation survived the longest and was not retired until April 10, 1959 signaling the end of all passenger service on the WM. The company spent most of that decade shedding its money-losing trains.

For just a few years they were pulled by diesels; between May of 1953 and September of 1954 Western Maryland acquired four RS3's from Alco equipped with steam-generators (#192-194 and #197).

They featured an odd, high-short hood (for a steam generator and dynamic brakes) which contrasted their much lower long-hood earning them the nickname as "Hammerheads."

Despite the WM's 1959 cessation of services it continued running or hosting excursions through the Chessie System era of the 1970s; big steam like Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 #759 and Reading #2102 regularly plied its rails in addition to WM's own power such as F7's, FA-2's and even Geeps.

Baltimore-Elkins Day Express: (Baltimore - Cumberland - Elkins)

Elkins-Baltimore Day Express: (Elkins - Cumberland - Baltimore)

Baltimore-Hagerstown Express: (Baltimore - Hagerstown)

Hagerstown-Baltimore Express: (Hagerstown - Baltimore)

Baltimore-Pittsburgh Express: (Baltimore - Connellsville - Pittsburgh)

Pittsburgh-Baltimore Express: (Pittsburgh - Connellsville - Baltimore)

West Virginia Express: (Baltimore - Cumberland - Elkins)

Blue Mountain Express (Resort Special): (Baltimore - Blue Mountain House/Pen Mar, Maryland)

Blue Mountain (Resort Special): (Baltimore - Blue Mountain House/Pen Mar, Maryland)

Buena Vista (Resort Special): (Baltimore - Blue Mountain House/Pen Mar, Maryland)

Pen-Mar Express (Resort Special): (Baltimore - Blue Mountain House/Pen Mar, Maryland)

During the 1890s WM completed the second important link in its "Alphabet Route." First, in 1892 it opened the 14-mile Potomac Valley Rail Road between Williamsport and Big Pool, Maryland, crossing the Potomac River there to complete a connection with the B&O main line at Cherry Run, West Virginia.

Second, the WM collaborated with the Philadelphia & Reading (Reading) to open a corridor between Hagerstown and Quinsonia, Pennsylvania. It was built as the Washington & Franklin Railway, presenting a more direct route between Hagerstown and Shippensburg, finished in March of 1899.

Western Maryland 2-8-0 #754 lays over at the engine terminal in Ridgeley, West Virginia on September 15, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Western Maryland 2-8-0 #754 lays over at the engine terminal in Ridgeley, West Virginia on September 15, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.The link allowed freight to flow from Midwestern points along the B&O to the Northeast via P&R rails. During late February of 1902 Hood gave up his post, a turn of events that signaled an entirely new direction for the company.

The city of Baltimore had been funding much of the railroad's construction and expansion during this time. However, it had not been reimbursed. As Zimmermann and Cook note, the total figure had ballooned to nearly $9 million.

George Gould

To recoup those expenses, offers were solicited and on May 7, 1902 Western Maryland was purchased by the Fuller Syndicate, led by George Gould who had lofty expectations for the WM as another puzzle piece in completing his father's vision of a true, coast-to-coast transcontinental railroad.

At the time he already controlled the Western Pacific, Rio Grande Western/Denver & Rio Grande, Missouri Pacific, Wabash Railroad, Wheeling & Lake Erie, and Wabash-Pittsburgh Terminal Railway. The new owners immediately put their plans into action by significantly upgrading the property.

The first project involved opening a deep water port at Port Covington, just southeast of Baltimore along the Chesapeake Bay.

The facility featured freight and coal piers as well as transfer ramps for carferry service and became WM's tidewater outlet. Then, on August 1, 1903 construction commenced to reach Maryland's largest western city, Cumberland.

The line opened to freight trains on March 15, 1906 while passenger service launched a few months later on June 17th. There, it linked up with another Gould property, the West Virginia Central & Pittsburg Railway.

System Map (1969)

He had originally acquired the line in January of 1902 and then transferred it over to the WM on November 1, 1905. The WVC&P blossomed into the railroad's coal route, channeling vast amounts of black diamonds out of the east/central mountains of West Virginia.

It was the dream of Henry Davis, originally chartered as the Potomac & Piedmont Coal & Railroad Company of 1866 and changed to the WVC&P in 1881. It completed its main line between Cumberland and Elkins, West Virginia during 1889.

System Map (1934)

The WVC&P continued to expand after WM ownership with lines snaking to the west and south of Elkins. These branches garnered a mix of coal and lumber while interchanges were established with the B&O (Belington) and Chesapeake & Ohio (Durbin). There were also exclusive coal branches dotting the main line northeast of Elkins.

The Western Maryland's operations in the Mountain State truly exemplified railroading in this region carrying tight curves and stiff grades while passing through rural small towns within the heart of Appalachia. Incredibly, many lines here survived into the 1980s and some even remain in service today.

Way off the beaten path in the hollers of West Virginia, Western Maryland RS3 #187 and a trio of F7A's run the GC&E Subdivision (built as the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk Railroad) near Laurel Bank along the Elk River (and the location of a small yard) during the 1970's. This branch to Webster Springs once handled coal and timber products (logs/lumber). It survived into the CSX era and the rails remain in place but have not seen a train since the mid-1990's. The right-of-way is owned by the West Virginia State Rail Authority. Wade Massie collection.

Way off the beaten path in the hollers of West Virginia, Western Maryland RS3 #187 and a trio of F7A's run the GC&E Subdivision (built as the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk Railroad) near Laurel Bank along the Elk River (and the location of a small yard) during the 1970's. This branch to Webster Springs once handled coal and timber products (logs/lumber). It survived into the CSX era and the rails remain in place but have not seen a train since the mid-1990's. The right-of-way is owned by the West Virginia State Rail Authority. Wade Massie collection.The last initiative Gould oversaw during his reign was the addition of the small Georges Creek & Cumberland Railway in January of 1907, which ran west from Cumberland, through the Narrows and reached mines around Midland to the southeast and a connection with the PRR at Ellerslie, Pennsylvania just across the state line.

As Gould attempted to complete his transcontinental railroad he overextended his financial resources and lost control of his portfolio.

The Western Maryland Rail Road entered bankruptcy on March 6, 1908 and was reorganized as the Western Maryland Railway on December 1, 1909 with its receivership ending on January 1, 1910.

Gould had been trying to complete his planned extension to Connellsville, Pennsylvania when his empire collapsed but had secured an important corridor through the Cumberland Narrows via the GC&C. New ownership carried on with this plan, beginning further westward construction during April of 1910.

The appropriately-named Connellsville Extension was built to very high standards; the 86-mile line featured relatively modest grades and designed for the purpose of future double-tracking, which was never carried out.

Its toughest territory was the 23 miles heading west from Cumberland where the route tackled Sand Patch via a 1.75% grade. The line summited at Deal and gradually followed a 0.80% to 0.60% descent into Connellsville.

Along the way four bores were needed (Big Savage Tunnel, Borden Tunnel, Brush Tunnel, and Pinkerton Tunnel) as well as two majestic bridges (1,908-foot Salisbury Viaduct and Keystone Viaduct). Finally, there was the sweeping Helmstetters Curve.

Located about seven railroad miles west of Cumberland, just outside of the small town of Corriganville, Maryland, engineers had to figure out how to span the Cash Valley. To do so they constructed a hairpin curve, originally via a trestle and then later covered with fill. It became a photogenic location, named after the local farm which sat near the right-of-way.

The Connellsville Extension was finished on August 1, 1912 and opened a western connection with the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie. Its most important interchange here, however, took place when the Pittsburgh & West Virginia finally completed its eastern link to Connellsville via Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh Junction, Ohio in the spring of 1931.

Soon afterward the "Alphabet Route" was launched. This consortium of eight different carriers:

- Nickel Plate Road

- Wheeling & Lake Erie

- Pittsburgh & West Virginia

- Reading Railroad

- Western Maryland

- Central Railroad of New Jersey,

- Lehigh & Hudson River,

- New York, New Haven & Hartford

Western Maryland chop nose GP7 #20 and a group of FA-2's run light between helper assignments at Williamsport, Maryland on October 17, 1970. Author's collection.

Western Maryland chop nose GP7 #20 and a group of FA-2's run light between helper assignments at Williamsport, Maryland on October 17, 1970. Author's collection.These railroads offered customers high-speed freight service between Baltimore/New York/Philadelphia/Boston and Chicago as an alternative to the major eastern trunk lines (Baltimore & Ohio, New York Central, and Pennsylvania). The service was successful for many years until the 1970s when mergers made the idea largely redundant.

Into The Modern Era?

While some segments of the WM abandoned under the Chessie System could arguably still be viable, profitable lines (such as the Connellsville Extension and its easier grade over Sand Patch) the entire network almost certainly would not have survived into the modern era.

The first blow came in 1959 when the St. Lawrence Seaway opened. This waterway provided a seagoing exit out of the Great Lakes and greatly hurt all eastern carriers which handled heavy export grain tonnage, including the WM at Port Covington.

Into the 1960s the railroad's coal business was playing out and its lumber shipments had long since evaporated. The merger movement began in the 1960s, and with the collapse of Penn Central in 1970 bridge routes like the WM were in their twilight.

With the formation of Conrail in 1976, and the future creation of CSX and Norfolk Southern, Western Maryland would have been a tiny fish surrounded by gigantic competitors.

It is somewhat ironic how swiftly the railroad was abandoned under Chessie considering it remained profitable right up until the takeover thanks to its many years of exemplary management.

While the Western Maryland operated a myriad of other feeder and branch lines the Thomas Subdivision, Connellsville Subdivision, East Subdivision, and West Subdivision comprised the railroad's important corridors.

The WM's entire 835-mile network could be broken down into two primary segments; its Connellsville - Shippensburg route which carried expedited, time freights and the Elkins-Baltimore segment moving primarily coal and related natural resources (coke and lumber) to tidewater.

In addition, the WM operated a handful of branches which were entirely disconnected from its network. In September of 1916 it acquired the Fairmont Helen's Run Railway Company running just over 6 miles from Chiefton to Ida May, West Virginia.

A year later it added the nearby Fairmont Bingamon Railway Company in December of 1917 which maintained another small segment of trackage between Hutchinson and Josephine. Both branches were located near Fairmont and to reach them the WM maintained trackage rights over the B&O via Bowest Yard just outside Connellsville.

There was also the Somerset Coal Railway in Pennsylvania, formed in 1915 and operated by the Western Maryland. Running just 4 miles from Coal Junction and Gray it served two mines maintained by the Consolidation Coal Company.

The WM maintained additional trackage rights here over the B&O from Coal Junction to Rockwood where the famous "Gray Train" operated. While all of these disjointed lines may have added only a few miles to the WM's network they proved very important to its bottom line.

The branch to Ida May was especially noteworthy. The mine there was owned by Bethlehem Steel and during the 1950s produced an astounding 4,000 carloads a month! As Zimmerann and Cook point out that was more traffic than all of the WM's lines south of Cumberland generated.

Following the opening of the Connellsville Extension four final additions completed the modern Western Maryland system including the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk; West Virginia Midland; Chaffee Railroad; and the Cumberland & Pennsylvania.

An engineer poses from the cab of Western Maryland 4-6-2 #208 (K-2), circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.

An engineer poses from the cab of Western Maryland 4-6-2 #208 (K-2), circa 1950. American-Rails.com collection.These were all feeder operations producing coal and lumber. The first was the 1927 purchase of the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk Railroad.

The GC&E was a longtime property of the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company, running 74 miles from a connection along the WM's Durbin Branch at Cheat Junction to Bergoo via Spruce and Cass.

The route featured steep grades and sharp curves and was noteworthy as having the highest main line above sea level in the eastern United States, Summit Cut, near Spruce with an elevation of 4,066.6 feet.

Due to the rugged, sawtooth-like profile south of Cumberland all of these lines were operated by 2-8-0 Consolidations where Class H-7's and H-8's regularly roamed.

They offered ample power with a short wheelbase that could readily handle the roller-coaster territory. The GC&E snaked its way along the Shaver's Fork of the Cheat River before cutting across the Tygart Valley River to the west at Spruce and reaching Slaty Fork.

From there, rails wound their way first north, then westward along the Elk River and terminated at Bergoo.

Operations Around Elkins

The Western Maryland's most noteworthy branch beyond Elkins included its lines south to Durbin and Webster Springs.

The former location concluded a long sought connection with the Chesapeake & Ohio by Henry Davis's, West Virginia Central & Pittsburg Railway.

On December 14, 1899 a charter was issued for the Coal & Iron Railway (C&I), a wholly-owned subsidiary of the WVC&P. After initially disagreeing on the junction point the C&O and WVC&P settled on Durbin as the new interchange.

Building the branch, extending south from Elkins, was difficult and expensive as the geography was rugged with grades exceeded 2% in some locations.

The Cheat and Shavers Mountains had to be crossed and doing so meant tunnels beneath each; Tunnel #1 was bored under Cheat Mountain south of Canfield while Tunnel #2 was located near Glady under Shavers Mountain.

Not surprisingly, the work was slow although there was no rush towards completion since the C&O was still in the process of finishing its own line. By late 1902 service was opened to Bemis and finally completed to Durbin on July 27, 1903 according to William McNeel’s book, “The Durbin Route.”

From the station in Elkins the route’s entire length spanned 46.9 miles. Under the WM the route was known as the Durbin Subdivision or Durbin Branch.

Speed Lettering Logo

The West Virginia Central & Pittsburg had been formed in 1881 by Davis after renaming his Potomac & Piedmont Coal & Railroad Company that year in an effort to further extend lines into West Virginia to tap the region’s timber and coal reserves.

It initially began construction in April of 1880 near Bloomington, West Virginia at an interchange with the B&O now known as West Virginia Junction.

The grades were not terrible until engineers were stuck with trying to find a way down the rugged Blackwater Canyon; what became known as Black Fork Grade descended from Thomas reaching grades exceeding 3% before leveling off at Hendricks.

Another stiff encounter south of Parsons with grades over 2% were endured to Haddix before reaching Elkins in 1889 (then known as Leadsville). A branch extended beyond Elkins to Dailey and as far as Huttonsville (the "Huttonsville Branch"), which was completed in 1899.

In 1891 another branch opened westward 16 miles to Belington where a connection was reached with the Baltimore & Ohio's Grafton & Greenbrier Railroad. Originally built as a narrow-gauge (3-foot) it was standard-gauged in 1892.

Finally, a northeasterly extension here was opened as far as Weaver in 1899 through the subsidiary Belington & Beaver Creek to tap additional coal mines.

What many may not realize is that today's popular Cass Scenic Railroad, running from Cass, West Virginia to Spruce and Bald Knob, was once a much larger operation.

According to William Warden's book, "West Virginia Logging Railroads," the project was launched by the West Virginia Spruce Lumber Company (a division of West Virginia Pulp & Paper) when it purchased 173,000 acres of property near Cass to tap the area's rich timber tracts.

It could not begin rail operations until the Chesapeake & Ohio's Greenbrier Branch was completed from the C&O main line at Ronceverte to Durbin in December of 1903 where it later met the Coal & Iron Railway, a future WM subsidiary. With rail service now established the Greenbrier & Elk Railroad was chartered to begin hauling logs off the mountain.

The section to Spruce (8 miles) featured very stiff grades, requiring the use of Shay geared steam locomotives. This now-ghost town once hosted a pulp peeling mill, company store, railroad facilities, and housing for workers.

In 1910 the railroad was renamed as the Greenbrier, Cheat & Elk and continued expanding, connecting with the Coal & Iron at Cheat Junction to the north and as far west as Bergoo. At its peak the GC&E maintained some 175 miles, earning it recognition as the longest logging railroad in the country.

The Western Maryland acquired control of the GC&E's lines north and west of Spruce in 1927, which became its Elk River Branch. The WM's interest lay less in lumber/logging and more in the idea of expanded coal operations.

It upgraded the property with heavier rail and improved ballasting while also straightening some of the worst curves. However, the line still retained a very rugged profile as it was never truly intended for main line service.

Zimmermann and Cook point out it needed Maney guard rails for the worst curves, a feature usually found on interurban operations.

Incredibly, the WM actually expanded beyond the tiny rural hamlet of Bergoo as it looked to bolster its coal business. In 1929 it acquired the West Virginia Midland Railroad, a system first planned to narrow-gauge standards.

The WVM was the most isolated segment of the WM. Its original promoter was the Holly River Boom & Lumber company, which opened a standard-gauge private line from Holly, where its mill was located, to a connection with the B&O at Palmer Junction.

First established in 1893, according to George Hilton's book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the railroad opened for service on November 1, 1894.

Including branches it maintained about 12 mile of track. On July 1, 1896 the property was reorganized as the Holly River Railroad, a common-carrier, and acquired by John McGaw to serve lumber mills.

He again changed the name as the Holly River & Addison Railway on September 10, 1898, which acquired the standard-gauged property and began constructing narrow-gauge lines to Diana (18 miles) and Jumbo (22 miles), opening in 1899. Another extension was completed to Webster Springs (12 miles) on May 26, 1902.

After this time his operation slowly declined. It was reorganized as the West Virginia Midland Railroad on April 6, 1906 and he retained control until another receivership in 1920. In 1924 the entire property was sold and renamed as the West Virginia Midland Railway.

In 1925 one final, dual-gauge extension (three rails for standard and narrow-gauge operation) was carried out when 12 miles opened from Webster Springs to the GC&E at Bergoo. Ironically, for all of this construction only the latter segment, acquired by the GC&E in 1929, was retained under the Western Maryland.

Next, there was the Chaffee Railroad also added in 1929, which became WM's Chaffee Branch. This little operation ran from the main line at Chaffee, West Virginia to serve mines at nearby Vindex, Maryland. It featured brutal grades of over 9% and curves as sharp as 23.5° requiring the use of Shays.

The second-largest ever built was #6, an incredible 162-ton, three truck machine. When outshopped by the Lima Locomotive Works in May of 1945 it was the last of its kind ever-constructed. Unfortunately, she spent only five years in service before the Chaffee Branch played out in 1950.

The locomotive sat stored until 1953 when it operated under its own power to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum for display. It remained here until 1980. It was then sent to Cass for restoration and excursion service.

The big Shay remains in operation today as a fan favorite. Finally, was the Cumberland & Pennsylvania Railroad running between Westernport and Borden Shaft, Maryland. This was WM's very last addition, acquired from Consolidated Coal in May of 1944.

The C&P had long been used as trackage rights between Westernport and Lonaconing Junction to gain access to mines WM served in the area after abandoning most of the old Georges Creek & Cumberland. The WM in its final form was vastly different from the railroad first envisioned.

As Ross Grenard and John Krause point out in their book, "Steam In The Alleghenies: Western Maryland," it was initially planned to handle only agricultural products from Carroll and Frederick Counties to Baltimore.

The modern, high-speed Western Maryland of the 20th century, transporting all types of freight from coal to merchandise, would certainly have impressed them. The "Wild Mary" earned a reputation for having extremely fast, efficient, and high quality service.

It prided itself greatly on this and "The Fast Freight Line" was much more than just a slogan. In 1940 it also introduced a "Fireball" herald on twelve new 4-6-6-4's, products of Baldwin. to showcase its high-speed service. The "Fireball" logo was later replaced with the stylized speed-lettering in 1952 on freight cars and 1954 on diesels.

The Western Maryland Railway logo, typically presented as part of the fabled "Fireball" design. Author's work.

The Western Maryland Railway logo, typically presented as part of the fabled "Fireball" design. Author's work.Over a decade later the WM updated its livery for a final time when the red and white "Circus" scheme, with speed-lettering, adorned new SD40's in June of 1969.

The powerful Challengers were designed for expedited service between Hagerstown and Connellsville but proved very hard on the track with a tendency to slip.

As a result the disappointing articulateds were banished east of Cumberland and eventually retired in 1953. They were replaced with twelve 4-8-4's, "Potomacs," also Baldwin products outshopped in 1947 (the last new examples of that type ever built for an American railroad), working the line east of Cumberland while the Challengers handled assignments over the Connellsville Extension.

Alas, even they saw short careers, replaced by diesels in 1954. The railroad experimented with diesels from American Locomotive, Baldwin, Electro-Motive, and even General Electric 44-tonners to work Port Covington. In time, however, it best liked EMD products purchasing its only second-generation models from the builder.

The WM, as a truly independent carrier, ended in 1964 when the Chesapeake & Ohio and B&O jointly applied to acquire the WM, which was granted by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

Under this setup the Western Maryland Railway continued to operate mostly independent until the 1972 formation of Chessie System, Inc.

The new holding company controlled all three roads and, after its creation, WM began disappearing from both an operating as well as visual standpoint.

Its famous speed-lettering and Circus livery vanished beneath Chessie's new scheme of Federal Yellow and Enchantment Blue with bands of Vermillion which showcased a silhouetted Chess-"C" kitten.

Only a sub-lettering of "WM" recognized the locomotives as Wild Mary power. Unfortunately, new ownership was also not kind to WM's network.

Within a year the company filed a petition with the ICC on June 11, 1973 to abandon 125 miles of WM's main line between Hancock, Maryland and Connellsville, Pennsylvania, except for a segment between Cumberland and Frostburg.

The request was granted in early 1975 and on April 7, 1976 most of the Connellsville Extension was declared out of service. At around the same time the main line between Westminster and Cedarhurst, Maryland was closed after Hurricane Agnes knocked it out in June of 1972.

It was briefly restored, and then washed away by another hurricane three years later. Chessie saw no need for additional repairs and was successful in abandoning the trackage. In 1973 the WM's once important terminal at Port Covington closed and all operations were handled via B&O's nearby Curtis Bay Piers.

Corridor Abandonment

By the end of the decade Chessie had closed or significantly reduced operations on most WM lines east and west of Cumberland. This left only the trackage southward into West Virginia, the Thomas Subdivision, and surrounding branches. As coal played out here it became increasingly less important by the early 1980s.

This region of the Mountain State was hit by severe flooding during the fall of 1985, which shut down parts of the Thomas Sub. Once more, the newly formed CSX refused repairs and it sat embargoed until abandonment a few years later. The Durbin Branch had became redundant after the C&O's Greenbrier Subdivision was abandoned in 1979.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 102 | 7/1941 | 1 |

| S2 | 125-127, 140-144 | 5/1943-11/1944 | 8 |

| S4 | 145-146 | 1/1951 | 2 |

| S6 | 151-152 | 3/1956 | 2 |

| RS2 | 180-184 | 6/1947-4/1950 | 5 |

| RS3 | 185-198 | 4/1953-9/1954 | 14 |

| FA-2 | 301-304 | 1/1951 | 4 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-660 | 103-105 | 7/18/1942-9/15/1942 | 3 |

| VO-660 | 1201 | 10/6/1941 | 1 |

| VO-1000 | 128 (1st) | 9/24/1943 | 1 |

| VO-1000 | 128 (2nd) | 9/25/1943 | 1 |

| VO-1000 | 130-132 | 11/12/1943-2/18/1944 | 3 |

| DRS-4-4-1500 | 170-172 | 7/5/1947-7/7/1948 | 3 |

| DS-4-4-1000 | 133-134 | 12/18/1946-12/28/1946 | 2 |

| AS16 | 173-176 | 5/13/1951-6/22/1951 | 4 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP7 | 20-23 | 4/1950 | 4 |

| GP9 | 25-45* | 5/1954-1957 | 21 |

| F3A | 51-52 | 6/1947 | 2 |

| F7A | 53-66, 231-242 | 3/1950-12/1952 | 26 |

| F7B | 53B-59B, 61B-65B (Odds): 231B-237B, 239B-243B (Odds) | 3/1950-12/1953 | 20 |

| BL2 | 81-82 | 10/1948 | 2 |

| GP35 | 501-505 | 11/1963 | 5 |

| GP40 | 3795-3799 | 8/1971 | 5 |

| GP40-2 | 4257-4261, 4312-4321, 4352-4371 | 2/1977-3/1979 | 35 |

| SD35 | 7432-7436 | 12/1964 | 5 |

| SD40 | 7445-7449, 7470-7474, 7495-7496 | 8/1966-7/1969 | 12 |

* GP9 #33 was built as Electro-Motive demonstrator #7257.

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 75-76 | 7/1943-8/1943 | 2 |

Thanks to John F. Kirkland's, "The Diesel Builders: Volume 3, Baldwin Locomotive Works," for help with compiling this diesel roster.

Western Maryland 2-8-0 #833 lays over at the engine terminal in Ridgeley, West Virginia on September 15, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Western Maryland 2-8-0 #833 lays over at the engine terminal in Ridgeley, West Virginia on September 15, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.Steam Roster (As Of 1947)

According to the book, "The Western Maryland Railway: Fireballs And Black Diamonds" by Roger Cook and Karl Zimmermann, Western Maryland's steamers generally carried the following assignments:

- 4-6-6-4 "Challengers" worked the Connellsville Extension.

- 4-8-4 "Potomacs" east of Cumberland.

- Big 'Mallets' tackled the Blue Ridge grades.

- Powerful 2-10-0 "Decapods" handled helper assignments.

- Heavy 2-8-0 "Consolidations" fought Black Fork Grade while their lighter counterparts were assigned to the branches south of Elkins.

- Shays worked the Chaffee Branch and sometimes on Black Fork.

- Finally, 4-6-2 "Pacifics" handled passenger services.

A Western Maryland freight fights upgrade over the legendary Black Fork Grade in West Virginia's Blackwater Canyon, circa 1952. The train had departed Elkins and was on its way to Thomas, and eventually Cumberland. Bill Price photo. American-Rails.com collection.

A Western Maryland freight fights upgrade over the legendary Black Fork Grade in West Virginia's Blackwater Canyon, circa 1952. The train had departed Elkins and was on its way to Thomas, and eventually Cumberland. Bill Price photo. American-Rails.com collection.Switchers

| Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1003-1005 | B-2 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| 1006,1008 | B-2a | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 1909 |

| 1009-1013 | B-3 | 0-6-0 | Baldwin | 1914 |

| 1051-1052 | C-1 | 0-8-0 | Western Maryland | 1926 |

| 1053 | C-1a | 0-8-0 | Western Maryland | 1927 |

| 1062-1067 | C-2 | 0-8-0 | Western Maryland | 1928-1930 |

| 1073 | C-2a | 0-8-0 | Western Maryland | 1935 |

Geared Designs

| Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Shay | 2-Truck | Lima | 1912 |

| 4 | Shay | 3-Truck | Lima | 1918 |

| 5 | Shay | 4-Truck | Lima | 1910 |

| 6 | Shay | 3-Truck | Lima | 1945 |

| 900 | Shay | 4-Truck | Lima | 1906 |

Western Maryland 4-6-2 #208 has a typical two-car passenger train near Westernport, Maryland on August 12, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Western Maryland 4-6-2 #208 has a typical two-car passenger train near Westernport, Maryland on August 12, 1953. Homer Newlon, Jr. photo. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Locomotives

| Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 151-160 | K-1 | 4-6-2 | Baldwin | 1909 |

| 201-209 | K-2 | 4-6-2 | Baldwin | 1912 |

Freight Locomotives

| Number(s) | Class | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 348 | H-3c | 2-8-0 | Baldwin/WM | 1892 |

| 351 | H-3f | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1895 |

| 406,409 | H-4 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1901 |

| 416 | H-4a | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1901 |

| 451-458 | H-4b | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1900 |

| 501,507 | H-5a | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| 506,509 | H-5 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| 513,518 | H-5a | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1905 |

| 615-616 | H-6 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1906 |

| 626 | H-6a | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1906 |

| 707-736 | H-7a | 2-8-0 | Alco/Richmond | 1911 |

| 750-764 | H-7b | 2-8-0 | Alco/Richmond | 1912 |

| 770-789 | H-8 | 2-8-0 | Alco | 1914 |

| 801-840 | H-9 | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1921 |

| 841-850 | H-9a | 2-8-0 | Baldwin | 1921 |

| 901-910 | L-1 | 2-8-8-2 | Lima | 1915 |

| 911-915 | L-1a | 2-8-8-2 | Lima | 1915 |

| 916-925 | L-2 | 2-8-8-2 | Lima | 1917 |

| 951-952 | M-1 | 2-6-6-2* | Baldwin | 1909 |

| 953-959 | M-1a | 2-6-6-2* | Baldwin | 1910-1911 |

| 1101-1110 | I-1 | 2-10-0 | Baldwin | 1918 |

| 1111-1130 | I-2 | 2-10-0 | Baldwin | 1927 |

| 1201-1212 | M-2 | 4-6-6-4 | Baldwin | 1940 |

| 1401-1412 | J-1 | 4-8-4 | Baldwin | 1947 |

* Rebuilt into 0-6-6-0's in 1927.

Thanks to the article, "Fast Freight Line" by author E.L. Thompson from the May, 1941 issue of Trains Magazine, for assistance with this steam roster.

As a result it too was shut down in 1985. During the 1990s, CSX wrapped up its operations on the old WM in West Virginia, closing or selling the remaining trackage. CSX Corporation had been formed on November 1, 1980 as a holding company which controlled rail and non-rail assets.

As the formal union of what was then Chessie System and Seaboard System slowly came together, CSX Transportation (CSXT) was born on July 1, 1986 to operate the company's railroad division.

According to Trains Magazine, the Western Maryland was the first Chessie road to disappear, merged into the B&O on May 1, 1983.

Today

Today only small sections of the WM are still active; the best known include the old Connellsville Extension operated by Western Maryland Scenic Railroad between Cumberland - Frostburg while the West Virginia Central operates over 100 miles of ex-B&O

and WM (the former Elkins Division) trackage between Tygart Junction, Belington, Elkins, and as far south as Big Cut/Spruce.

Both operations host popular excursions while CSX continues to operate short stretches of the WM in Maryland. Interestingly, the line to rural Webster Springs/Bergoo remains in place but has not witnessed a train since the early CSX era.

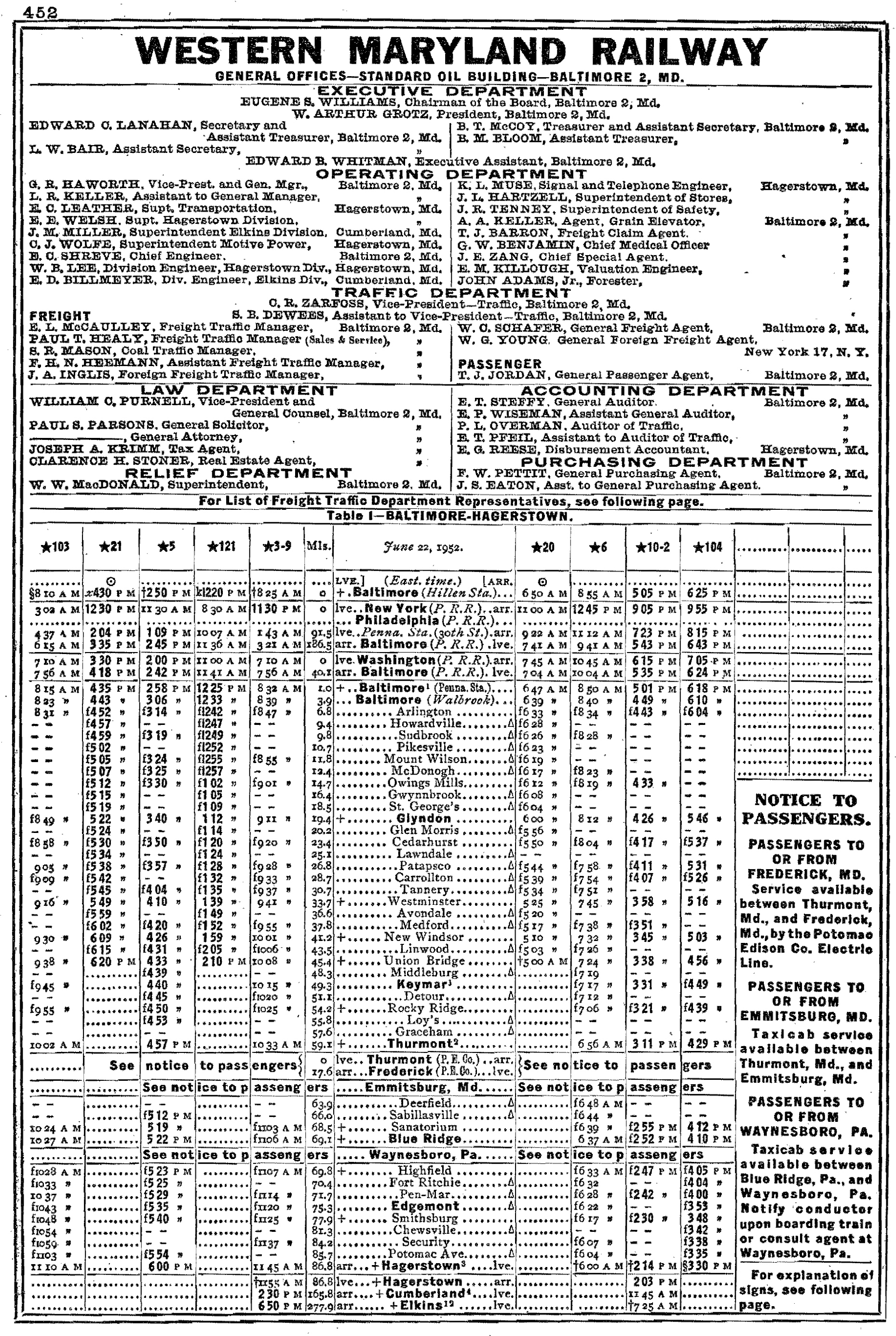

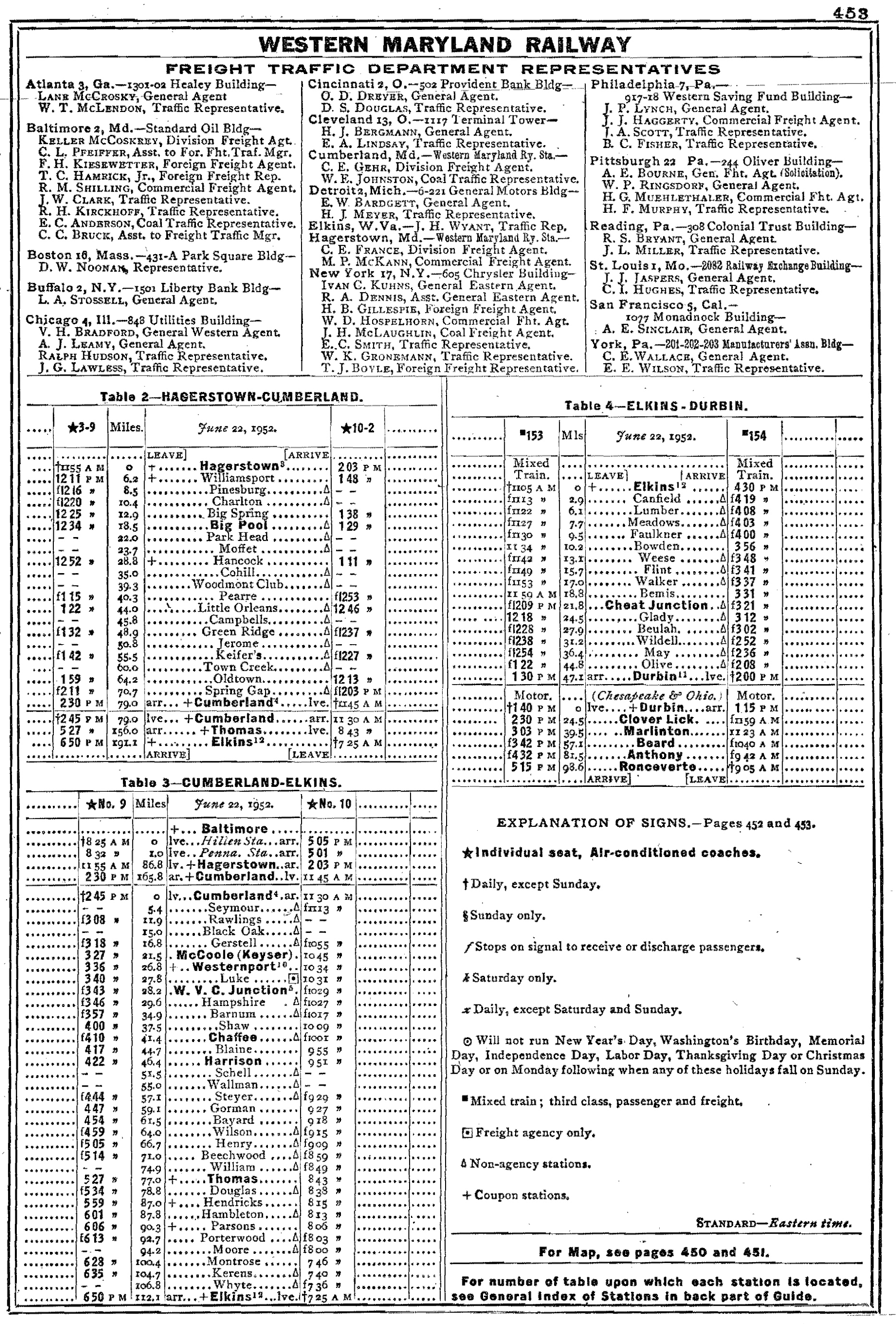

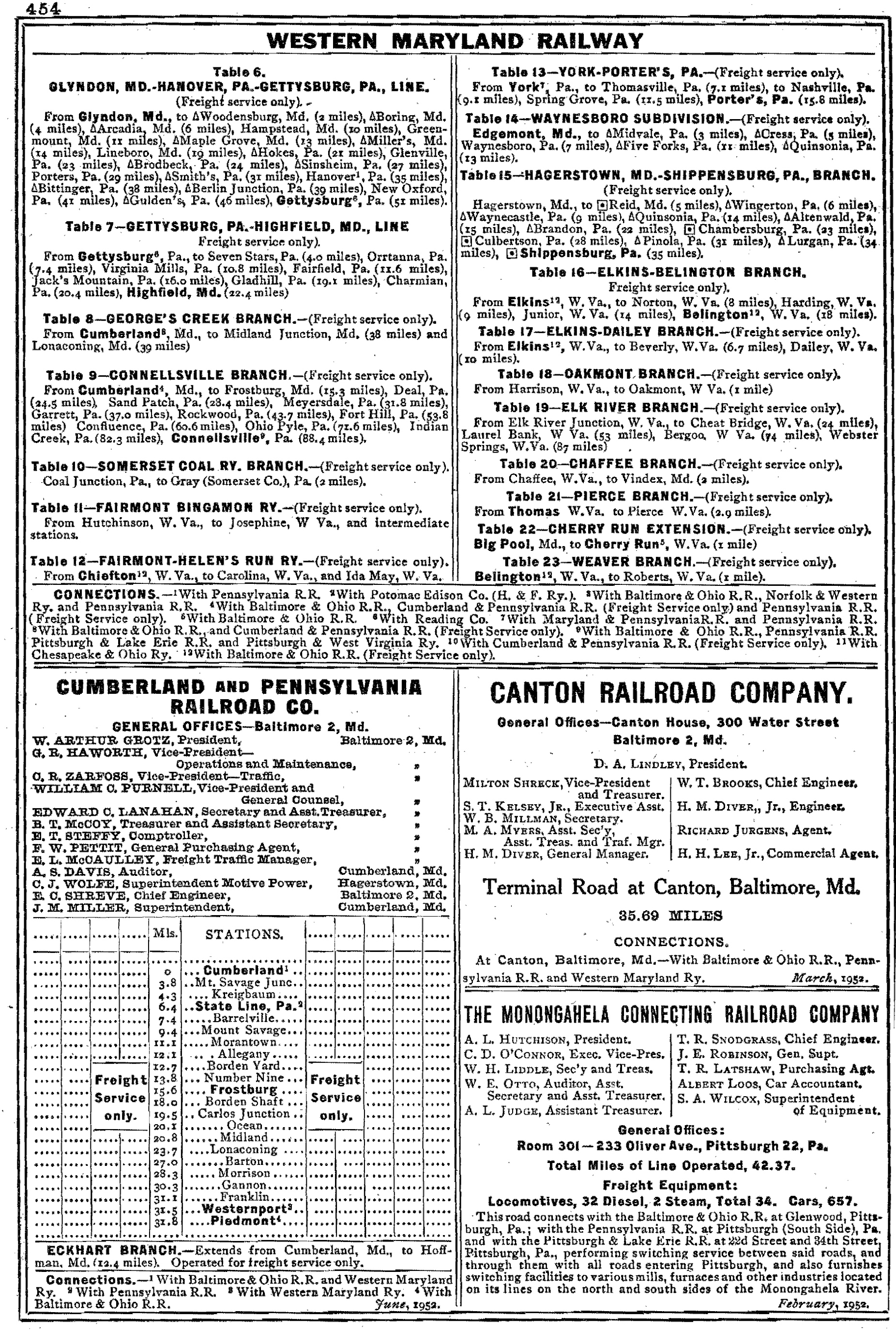

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-37): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 12:57 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-37 Mikes were itsdge steamers to enter service in the late 1920s. Today, all but two survive. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (K-36): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 15, 25 11:09 AM

The Rio Grande's K-36 2-8-2s were its last new Mikados purchased for narrow-gauge use. Today, all but one survives. -

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive.