"Stourbridge Lion" Locomotive: Facts, History, Photos

Last revised: February 22, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Stourbridge Lion carries particular importance in American railroad

history as it was the first steam locomotive to be successfully

operated during the summer of 1829, one year prior to the Baltimore

& Ohio's "Tom Thumb", designed by Peter Cooper.

There many "firsts" occurring between 1829 and 1830 in regards to steam power, as it became more and more obvious with each successful test that it was a proven method to move people and goods relatively efficiently and quickly (at least in regards to what was available at the time).

The Lion, purchased by the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, was not built in the United States but it did prove quite reliable, which is ironic considering after a successful round of testing railroad officials decided against using it.

Soon after its trials the locomotive was put into storage and slowly withered away afterwards through sale and salvage. Luckily, the main boiler survives today and is owned by the Smithsonian Institution although it is on loan to the renowned B&O Museum in Baltimore.

By the 1820s the idea of railroads being a vital mode of transportation in both the United States and England was gaining serious interest. It was the Brits who first successfully developed steam power when Richard Trevithick of England showcased his initial design on February 21, 1804.

By the 1820s a number of horse-powered or incline railways in the U.S. were either in the planning stages or under construction. One of these was the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company that was first chartered in 1823 to move anthracite coal from Carbondale, Pennsylvania to New York City.

The idea was to use a series of incline railroads that operated with stationary steam engines to move loads of coal up and down the mines around Cardondale to the canal located at Honesdale, Pennsylvania. From that point it would then be moved over the water to New York.

During the early 1820s many believed that canals would be the wave of the future in transportation as few gave much thought to the unproven steam locomotive to be either reliable or useful.

The D&H was able to complete its canal that began along Rondout Creek between Kingston and Rosendale, New York and headed southwest to Port Jervis using the Neversink River much of the way.

From there it connected to the Delaware River and traveled due west using the Delaware River and finally the Lackawaxen River to reach Honesdale (as you can see, much of the "canal" was actually just connections to major rivers).

The canal took less than a year to complete and was open by the spring of 1826. That April construction then began on the gravity line, which was its own company named the Delaware & Hudson Gravity Railroad.

By 1829 the planned 16-mile line between Honesdale and Carbondale only was in service for about three miles from Honesdale westward, crossing the Lackawaxen River in the process.

As early as 1827 when the railroad was still in construction the D&H's chief engineer at the time John B. Jervis was very interested in the development of the steam locomotive happening in England.

He decided to send his deputy engineer Horatio Allen to Britain on two missions; one was to purchase strap iron for the railroad and the other was to study the steam locomotives being constructed there.

Interestingly, despite his young age of only 25 Allen was given the responsibility of ordering up to four locomotives if he felt they would prove useful and reliable to the D&H's operations.

Upon arriving in 1828 he met with several builders including the Robert Stephenson & Company and John Urpeth Rastrick of Foster, Rastrick & Company.

He first talked with Robert Stephenson, who, along with his father George were widely regarded as the experts in the field of steam locomotive manufacturing.

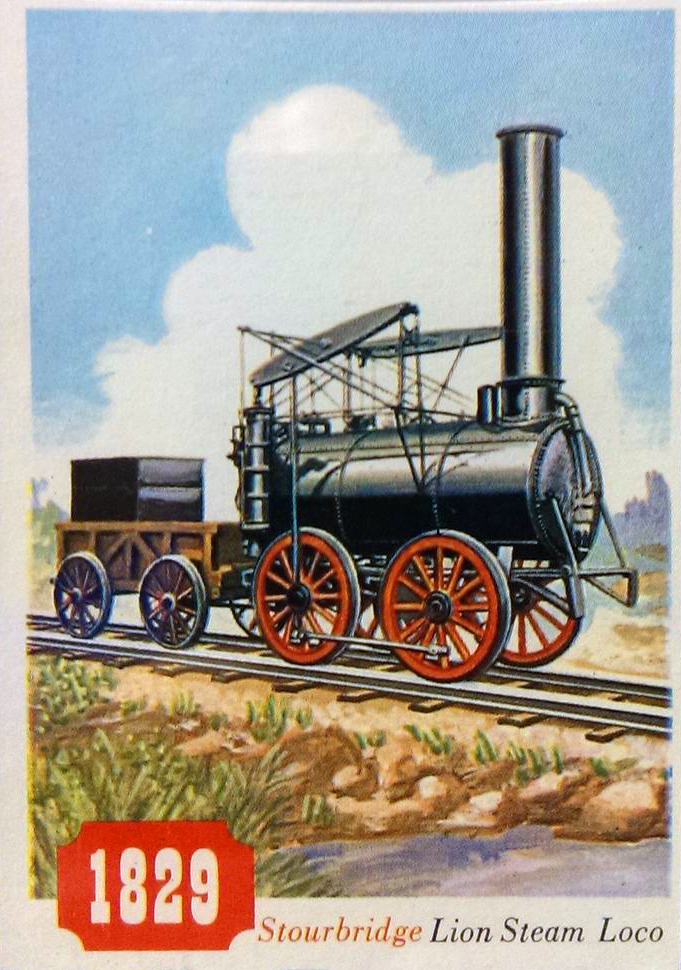

Allen decided to place an order with their company for one locomotive, the Pride of Newcastle. However, it was Rastrick's company that received the other three orders and the first unit it completed was the Stourbridge Lion so named for the lion painted on the nose and place were it was built, Stourbridge, England.

While there Allen also ordered the needed strap iron from a foundry in Wolverhampton, 390 tons worth. The cost of the Lion came to $2,914.90 and arrived back in New York on May 13, 1829 disassembled.

It was then sent to the West Point Foundry based in nearby Cold Spring for reassembly in testing. Its initial trials began on August 5, 1829 and proved to be in good working order.

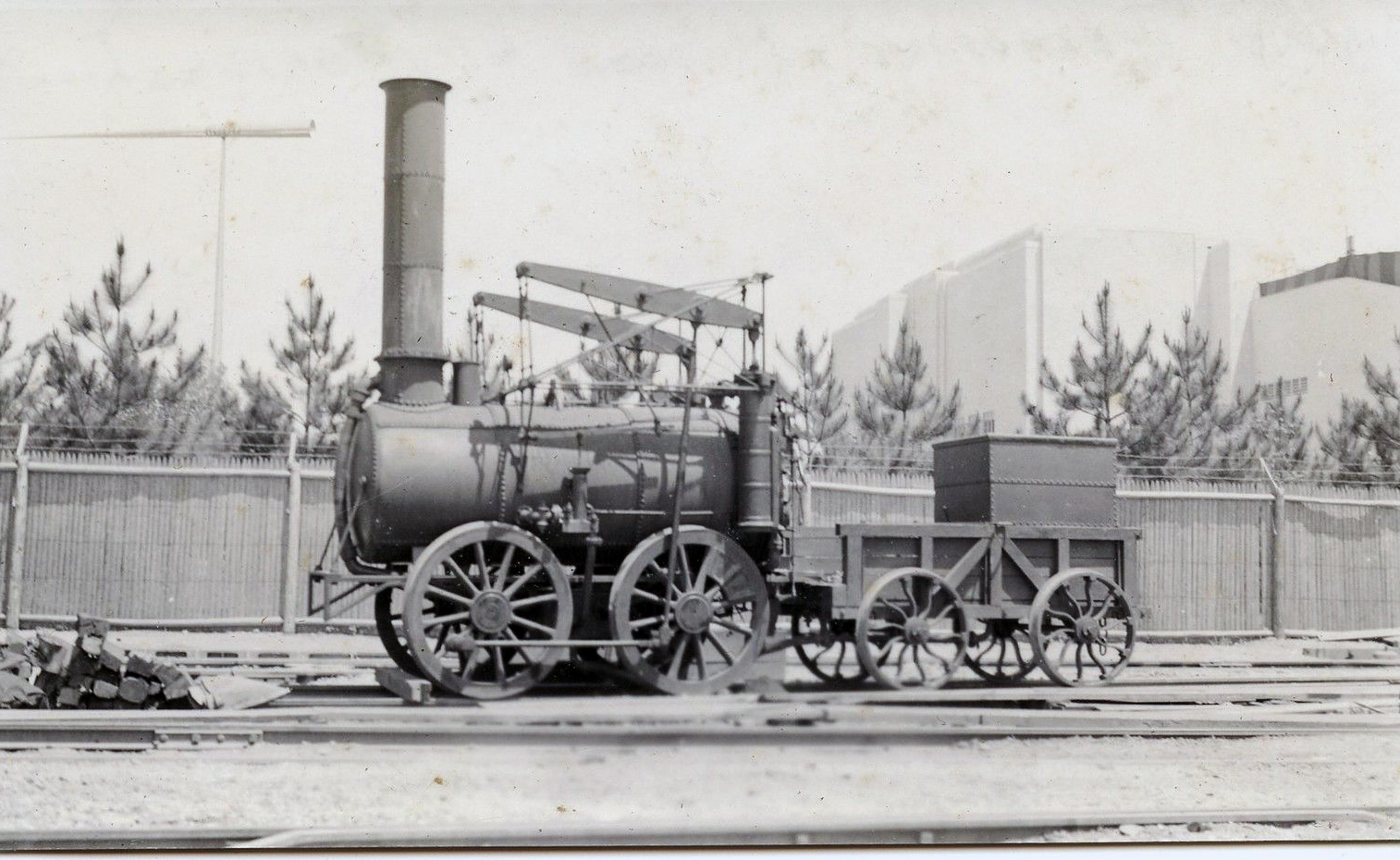

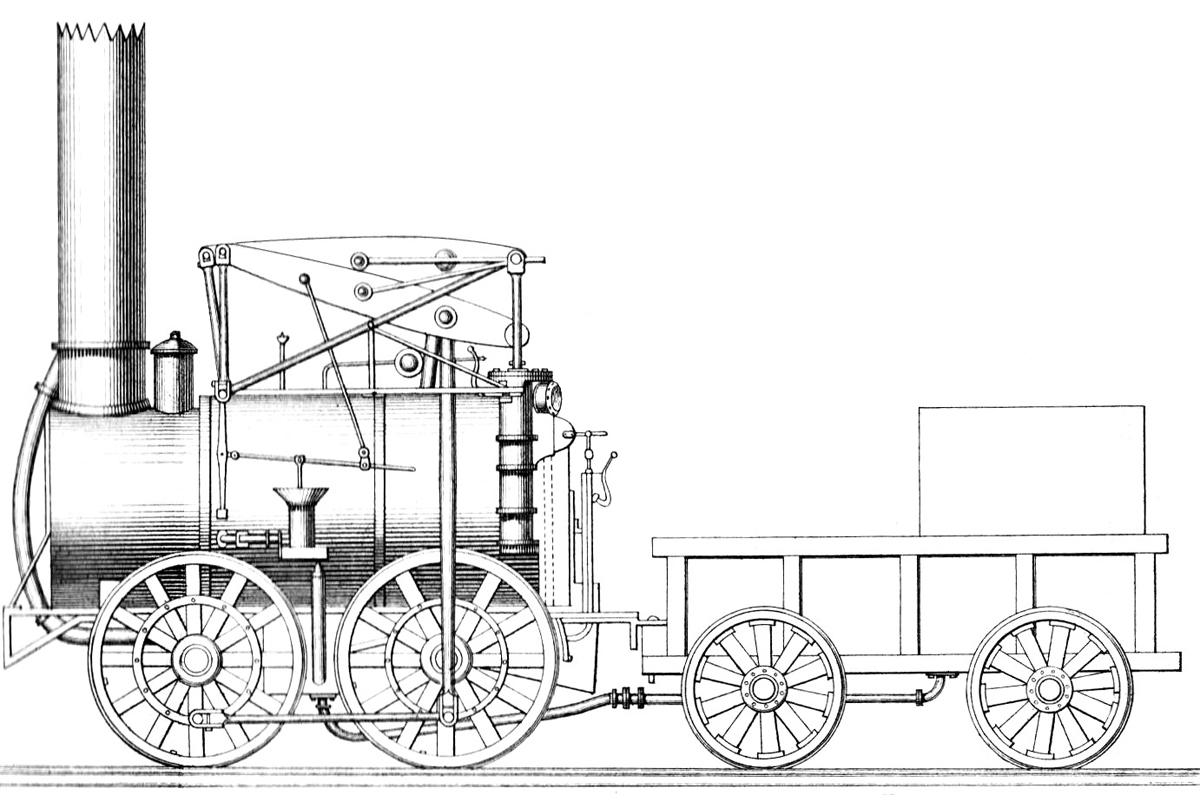

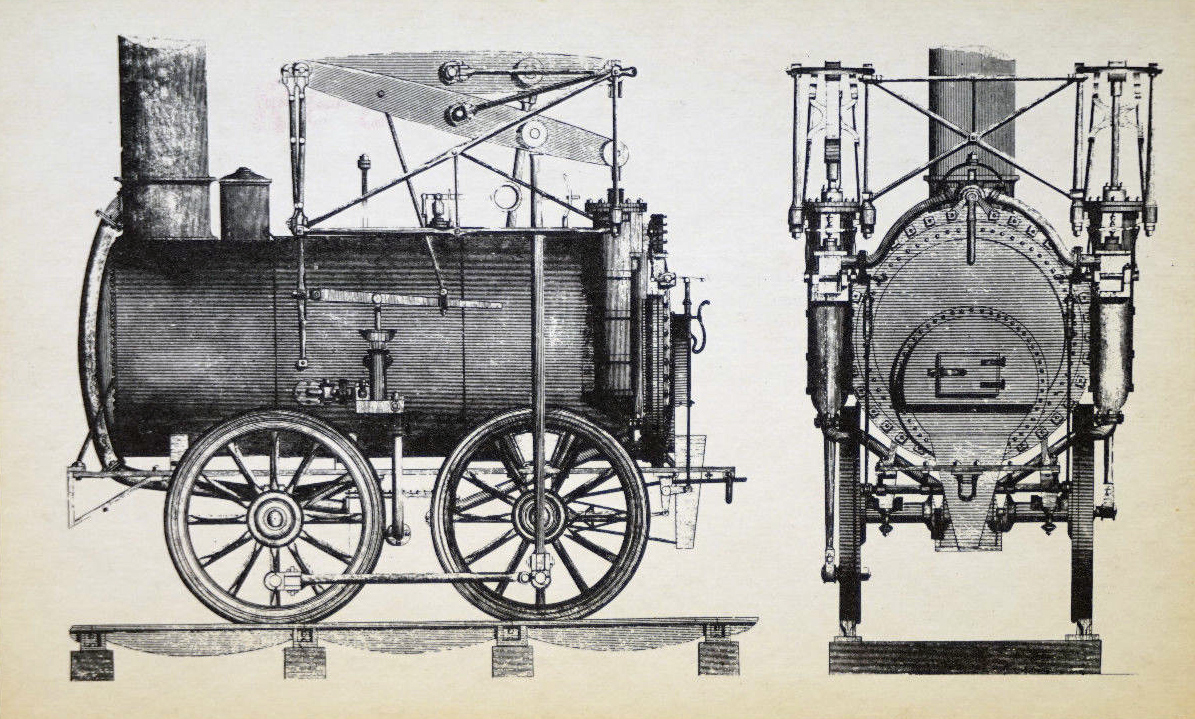

The Stourbridge Lion was designed somewhat differently than the American-built "Tom Thumb" and Best Friend of Charleston which began operating a year later.

It sported the now classic steam design with a horizontal boiler (and vertical smokestack) and driving rods followed by a trailing carriage (tender). Its wheels were built of wood with iron sheathing and featured an 0-4-0 wheel arrangement.

Pistons that sat atop the boiler were driven by steam and were connected to the driving rods which powered the Lion.

Despite the fact that Jervis had requested a locomotive that weighed only 4 tons so that the timber-constructed railroad could support the machine, the Lion weighed nearly 7.5 tons (which became a major issue later).

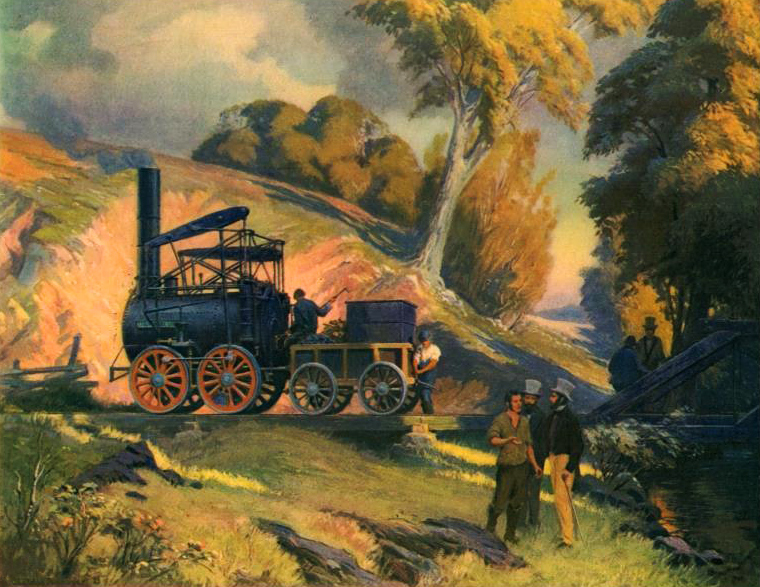

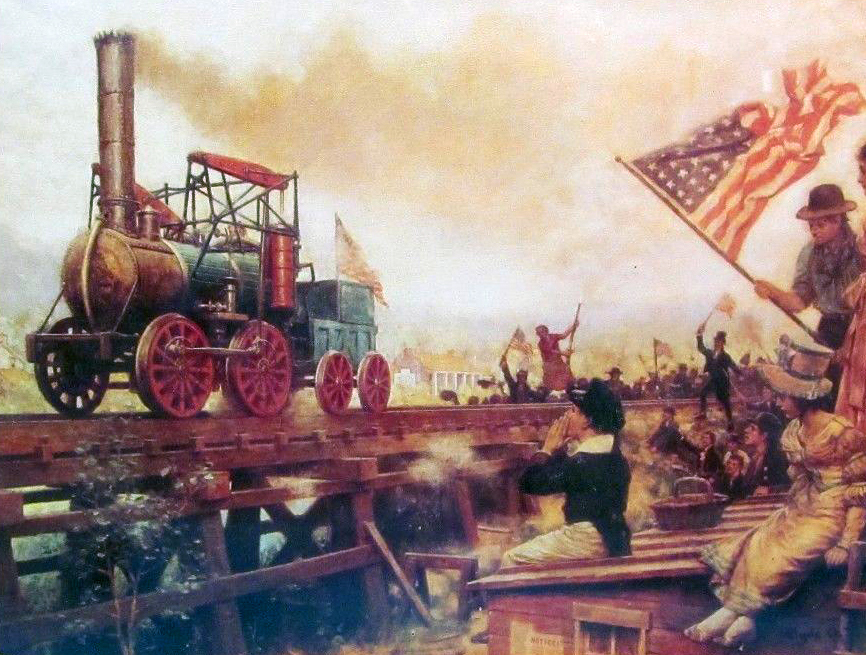

The locomotive's trial run took place on August 8, 1829 with Allen at the controls. This newfangled machine drew a large attendance to watch the event, many of whom were quite skeptical and fearful that it would explode.

As a result no one would ride the contraption but were stunned and amazed when it took off down the track without a problem and out of sight from the cheering crowd.

It likewise returned without a problem and not only convinced those in attendance of steam's future importance but also in the process entered the history books as the first locomotive ever operated in the United States.

In an odd twist of fate, its weight was too heavy for the track and resulted in D&H officials storing the locomotive instead of spending the necessary upgrades to use it in regular operation. It then sat out of sight after its initial trial run until 1834 when it was sold for its boiler to be used in a local foundry in Carbondale.

After realizing steam was not to be used on the D&H Allen left the company and became chief engineer of the South Carolina Canal And Rail Road a year later in 1830.

What remained of the Stourbridge Lion passed into many hands over the coming years and was eventually acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1890.

By that point the remaining boiler had been badly damaged through years of use, neglect, and even vandalism. An attempt to restore the locomotive has been attempted but without knowing what is original the project has never been completed.

Today, the boiler is on loan to the B&O Museum. Also, a replica built by the D&H using the original blueprints resides at the Wayne County Historical Society in Honesdale.

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive. -

Rio Grande K-27 "Mudhens" (2-8-2): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 05:40 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-27 of 2-8-2s were more commonly referred to as Mudhens by crews. They were the first to enter service and today two survive. -

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved.