King Street Station: A Seattle Landmark Still In Use Today

Last revised: September 9, 2024

By: Adam Burns

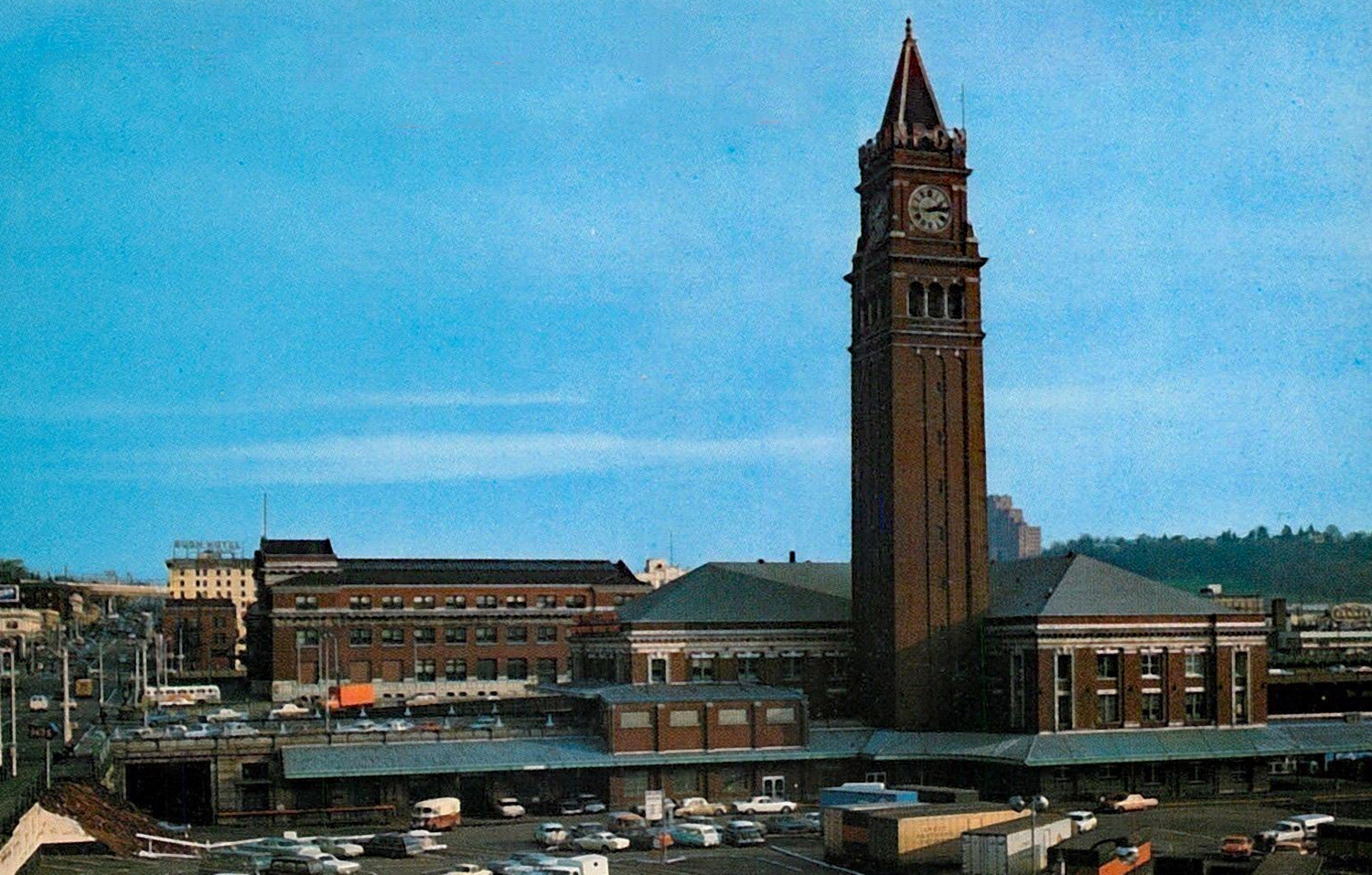

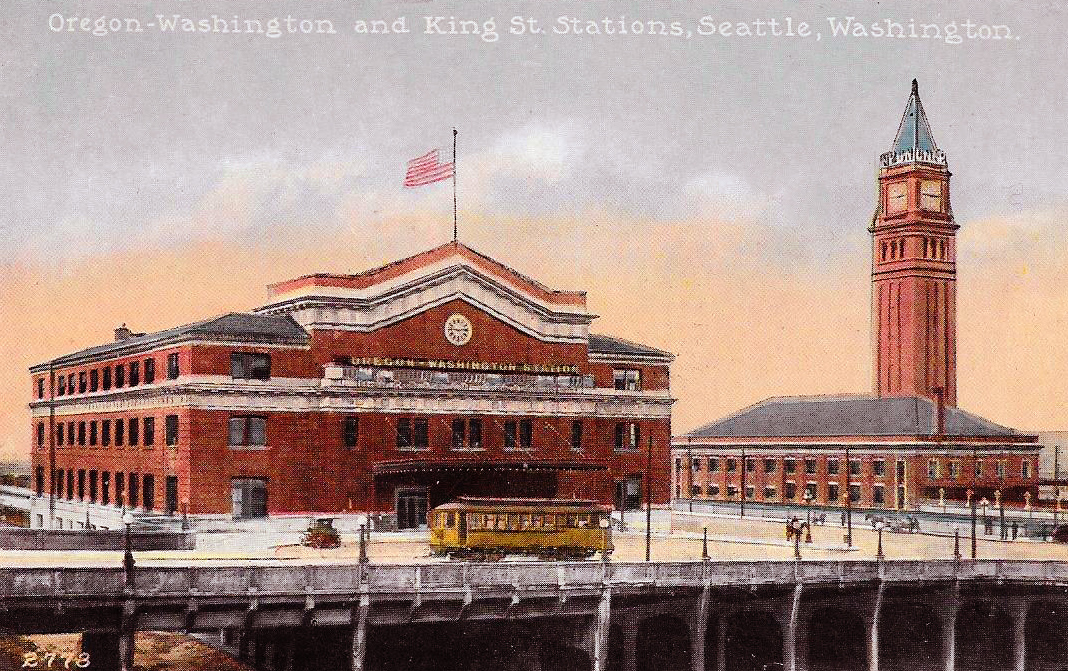

King Street Station is Seattle's last reminder of what once was regarding intercity passenger trains. At one time the city boasted two active terminals, which included Union Station located directly across the street.

This facility was served by Union Pacific and the Milwaukee Road until both lines stopped using it after Amtrak began service in 1971.

King Street held the honors of being the city's first large, modern terminal when it opened during the early 20th century, replacing an earlier structure for the Great Northern and Northern Pacific.

These two railroads were the first two transcontinental systems to the Puget Sound reaching there during the latter half of the 1800s.

Today, both buildings still stand and each has been graciously restored (thanks to the city's efforts in acquiring the former GN/NP facility from successor BNSF Railway in the mid-2000s) although only King Street still hosts trains.

Development

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in the spring of 1869 signaled the end of the American Frontier.

The project was carried out by the Union Pacific, building east, and Central Pacific, building west; once finished it offered a direct rail link across the western United States connecting Oakland/San Francisco, California with the rest of the country.

However, a great deal of work remained in opening new routes to other regions. Perhaps most notable was the Puget Sound with its growing timber economy and natural harbor to the Pacific Ocean.

The first railroad with intentions to reach the area was the Northern Pacific Railway Company, chartered by Congress and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1864.

The plan was straightforward, construct a new route connecting the Great Lakes with the Pacific Northwest. Of course, putting it into practice proved arduous and difficult.

To aid in its endeavor Congress allocated 60 million acres of undeveloped Frontier in exchange for the new railroad.

The most pressing concern was securing the necessary funding while the actual construction was challenging in its own right.

Since this region had no reliable transportation arteries and only a handful of small settlements dotting the landscape here and there surveyors, using little more than horses and their accompanying gear, were forced to hack their way through the underbrush to lay out a route.

According to Mike Schafer's, "More Classic American Railroads," rails were pushed from both the east and west; by 1873 a line connected Duluth, Minnesota with Bismarck, Dakota Territory while Tacoma (then the western rail head) was connected with Kalama, Washington to the south.

The railroads directors tapped Jay Cooke & Company and his financial connections to fund the project. Unfortunately, Cooke's bank not sell enough bonds to meet its obligations and went under in 1873, stalling further construction.

Under new ownership in 1878 the road's fortunes improved as new sources of revenue were achieved. After another decade of hard work the Northern Pacific was completed in 1883 with a ceremony held at Gold Creek, Montana on September 8th.

A little less than a year later, on July 1, 1884, grading commenced for direct NP service to Tacoma via the so-called Cascade Branch via Yakima and Ellensburg. This extension opened in the spring of 1888.

Finally, if it was not for the efforts of local Seattle citizens in the early 1870s its small hamlet of just 1,200 may have never been a part of Northern Pacific's network.

They successful petitioned then-president Henry Villard to push rails above Tacoma to their small town. The project began in the fall of 1882 and was completed by later September of 1883.

In the following years the Northern Pacific grew into a formidable western railroad, at its peak owning upwards of 7,000 route miles extending from Duluth to the Twin Cities and Spokane, Portland and Seattle via Helena, and Missoula, Montana.

It held a robust agricultural network of branch lines in the east and substantial timber holdings throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Its monopoly in the region, however, was short-lived. By the 1880s noted rail tycoon James J. Hill, the "Empire Builder," was eyeing his own Pacific Extension to the Puget Sound.

By the time he entered the railroad business Hill was already an accomplished entrepreneur having launched the successful Red River Transportation Company in 1870, which provided river-going services service between St. Paul and Winnipeg, Minnesota.

In 1878 he acquired the floundering St. Paul & Pacific along with business partners Norman Kittson (his steamboat company counterpart), Donald Smith, George Stephen and John Stewart Kennedy believing the bankrupt road had great potential.

Construction

A year later he formed the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba to push rails westward, reaching Great Falls, Montana in 1887.

Hill proved a very adept railroader. Understanding the region across northern Montana and North Dakota offered little freight potential he worked to build up local business while also realizing the need to establish the best possible route across the Pacific Northwest.

In 1889 he formed the Great Northern Railway and began the 800-mile extension from Havre, Montana to Seattle via Spokane and Everett, Washington.

The line was opened in 1893 and the railroad spent the next several years expanding its network, eventually owning a system covering more than 8,000 miles.

In time, the Great Northern; Northern Pacific; Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; and Spokane, Portland & Seattle came under common ownership to provide direct service from Chicago to Seattle/Portland.

With the arrival of the railroads, Seattle blossomed into the region's most important port city, which later included the Milwaukee Road and Union Pacific.

The NP and GN's first passenger terminal was located in downtown Seattle along the waterfront near Railroad Avenue (today's Alaskan Way).

As the Great Northern Historical Society points out this first facility was little more than a wooden shed and Seattle residents were rather embarrassed by its complete lack of architectural significance and facilities.

Interestingly, despite the city's growing stature, Hill remained indifferent to the problem. As a businessman he was focused on ways to make the Great Northern more money rather than worrying over a passenger facility. He is quoted as saying:

"It is more important for Seattle to have goods delivered cheaply rather than having a fancy depot."

A present-day view of King Street Station's restored main waiting room as it appeared on December 14, 2014. Photo by Wikipedia user, "ZhengZhou."

A present-day view of King Street Station's restored main waiting room as it appeared on December 14, 2014. Photo by Wikipedia user, "ZhengZhou."But as Seattle continued to expand even Hill recognized a prominent terminal would be needed to meet demand.

In 1903 he hired the noted architect firm of Reed & Stem (the partnership of Charles A. Reed and Allen H. Stem) based in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Their most famous commission was New York Central's breathtaking Grand Central Terminal (New York), completed in 1913; other well known terminals included Detroit's Michigan Central Station and Tacoma Union Station.

In addition to growing passenger demand the new terminal allowed GN to move its main line slightly away from the waterfront.

There was also a joint project carried out with Northern Pacific to construct a new freight yard along the former Tide Flats next to Puget Sound. Interestingly, for years the NP/GN offered the only intercity railroad station available to passengers heading to and from Seattle.

However, things finally changed in May of 1911 when what became known as Seattle Union Station opened (originally referred to as the Oregon & Washington Depot), serving the Union Pacific and Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific (Milwaukee Road).

The construction of King Street Station began in 1904; designed in the Beaux Arts style, with Neo-Classical touches, it featured red brick masonry with cut-stone trim and terra cotta decoration.

This architecture dated back to the mid-18th century and employed elements once commonly found in ancient Greece and Italy during the times of Roman rule, carrying on through the Renaissance era.

Its most prominent feature was a magnificent 245-foot clock tower closely modeled after the Campanile di San Marco in Venice, Italy.

Each tower face featured ornate mechanical clocks designed by the E. Howard & Company of Boston, Massachusetts which were lit at night.

To allow trains to operate through the terminal and eliminate a cumbersome stub-end setup the builders constructed a nearly mile long tunnel (5,245 feet) beneath the city (nearby Union Station lacked this feature).

The building's interior was also impressive with elaborate ceiling designs and marble used throughout (the station also featured a beautiful compass on the entry hall's floor named, appropriately enough, the "Compass Room").

It may seem hard to believe in today's world of towering skyscrapers but King Street Station was once the tallest building in Seattle and the only structure on the West Coast to feature such an impressive time piece at the time.

During the height of rail travel King Street found itself home to several named trains like:

- Northern Pacific's North Coast Limited and Mainstreeter

- Great Northern's Empire Builder, Western Star, International, Oriental Limited, and Cascadian

- Spokane, Portland & Seattle's Columbia River Express

While King Street never lost direct rail service as train travel declined in the 1950s so too did the building's upkeep and general appearance.

By the time Amtrak took over most intercity passenger services on May 1, 1971 much of station's marble had been removed and a bland, unattractive false ceiling covered the original.

Amtrak had no capital available to restore most of the terminals it owned or utilized and many of which, like King Street, had been severely neglected by the 1970s.

In addition, owner Burlington Northern placed microwave dishes on the clock tower further scarring its architectural significance.

After years of this rundown appearance Seattle and BNSF Railway agreed in March of 2008 for the city to acquire the property for a mere $10.

The first process of restoration occurred that same year when the microwave towers were removed and the clocks restored to working condition.

This ownership transfer also paved the way for nearly $30 million in restoration money; between 2010 and 2013 extensive work occurred on the building's interior and exterior to bring it up to modern standards (such as steps to help it survive an earthquake or seismic event, which is not uncommon in the Pacific Northwest) while also preserving as much of the original architecture as possible.

It was officially rededicated on April 24, 2013 and now appears largely as it did when it first opened in 1906. Today, the station is served by Amtrak and Sounder commuter trains, and one can still watch passing container/intermodal and other freight trains of the BNSF Railway.

Even better, King Street Station is now on the National Register of Historic Places, receiving that distinction in 1973, which will help preserve and secure its future.

Recent Articles

-

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad. -

Delaware Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:23 PM

Delaware may rank 49th in state size but has a long history with trains. Today, a few museums dot the region. -

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here.