"Kate Shelley '400'": C&NW's Post-1955 Iowa Service

Last revised: September 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Kate Shelley 400 was a very late addition to the Chicago & North Western's family of streamliners. The train was brought about by the loss of through service with Union Pacific's City fleet, which had switched to the Milwaukee Road in 1955 for its Chicago connection.

The Kate Shelley, named after a railroad heroine who saved a passenger train from a grim fate during the late 19th century, allowed the C&NW to continue providing service along its Omaha main line where it ran as far as Boone, Iowa when it first entered service.

Unfortunately, the train's initial routing was short-lived as it was soon cutback although it remained on the timetable, albeit as an unnamed run during its final years, until the start of Amtrak during the spring of 1971.

Since 1889 the 'North Western and Union Pacific had been working together closely to provide passengers service from Chicago to points across the West.

During the early years this included (UP) trains like the Overland Flyer (Chicago - Portland with connections to San Francisco) and Los Angeles Limited (Chicago - Los Angeles). On June 6, 1935 their transcontinental operations witnessed a significant upgrade when lightweight, diesel-powered trainsets were launched beginning with the City of Portland (the M-100001).

Photos

Chicago & North Western E7A #5015-A boards at DeKalb, Illinois with train #2, the eastbound "Kate Shelley '400'" on the morning of December 28, 1964. Roger Puta photo.

Chicago & North Western E7A #5015-A boards at DeKalb, Illinois with train #2, the eastbound "Kate Shelley '400'" on the morning of December 28, 1964. Roger Puta photo.History

This sleek new streamliner was soon followed by an entire fleet including the City of Los Angeles, City of San Francisco, and City of Denver.

The two railroads continued to partner for another twenty years until 1955 when UP became disenchanted with the C&NW's service and switched to the Milwaukee Road beginning on October 30th.

This left the 'North Western with no through, passenger trains along its Omaha main line leading to the inauguration of the Kate Shelley 400 between Chicago and Boone, Iowa.

At A Glance

1 (westbound) 2 (eastbound) | |

North Western Terminal (Chicago) Boone, Iowa Depot |

|

The train was named after Catherine "Kate" Shelley, an Irish immigrant who came to the United States soon after she was born and eventually settled in Boone County, Iowa.

She lived a quiet life for many years until July 6, 1881 when she heard a C&NW train crash into nearby Honey Creek (a single locomotive out checking track conditions), the result of flash floods caused by the day's severe thunderstorms.

Knowing that an eastbound passenger train would be passing through the area soon, Shelley rushed on foot and through bad weather to the local Moingona depot to warn of the washout and wrecked locomotive.

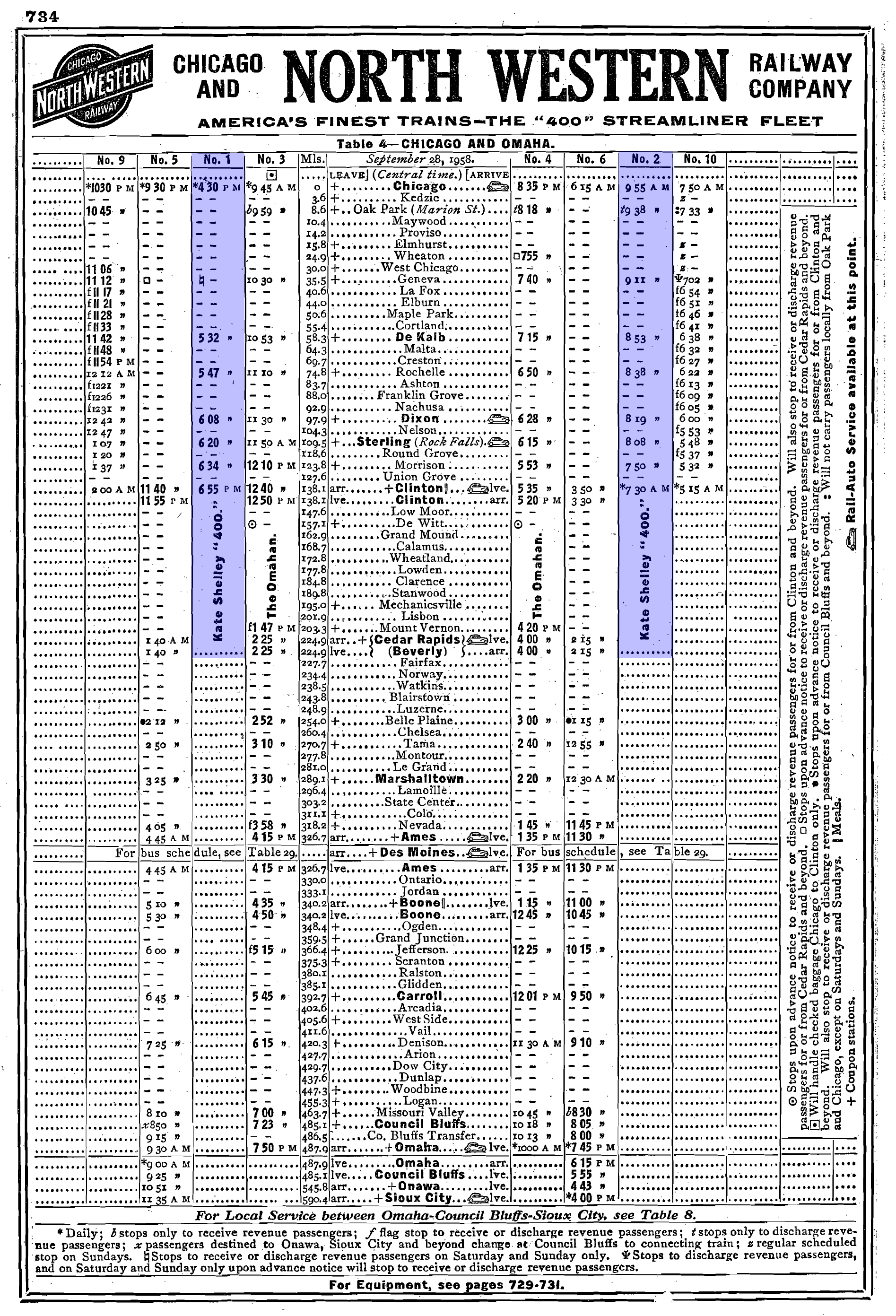

Timetable (1958)

Her heroic efforts saved the passenger train from impending disaster and led to the rescue of two of the crew involved in the washout. She was praised by the railroad, local community, and eventually became a national heroine.

The 'North Western went on to name a bridge after her in 1900 (still in use albeit since rebuilt) as well as a new streamliner years later. The Kate Shelley 400 was listed as trains #1 (westbound) and #2 (eastbound) on the C&NW's timetable.

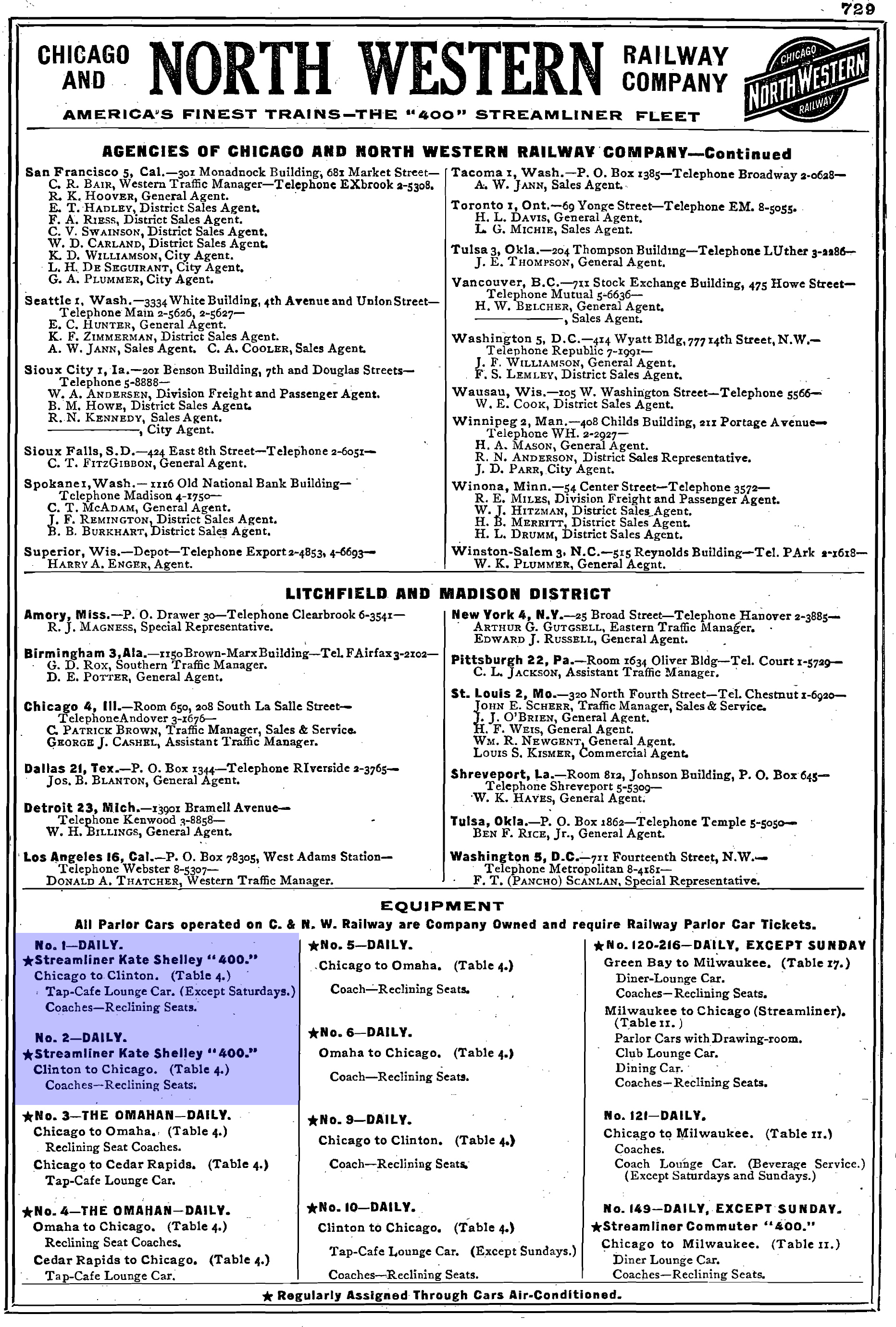

Its consist primarily included lightweight equipment featuring reclining seat coaches, a diner, lounges, and a parlor running a schedule of only a few hours from Chicago to Boone, 340 miles (as a dayliner, sleepers were not required). Initially, its equipment was made up of that formerly used on the City trains but this was later scattered throughout the 'North Western's fleet.

Consist (1958)

The Katy, as the train was also known by locals, was cutback to Cedar Rapids during August of 1956 and then a year later was truncated to Clinton, Iowa just 137 miles west of Chicago.

By 1961 the Kate Shelley 400 was the last named train still providing service on the 'North Western's Omaha line (running daily except Sunday) and after July 23, 1963 the name was quietly dropped altogether from the timetable. However, surprisingly the unnamed train continued to operate as a local, coach-only "streamliner" until the start of Amtrak on May 1, 1971.

As a fleet, the C&NW's famous 400s suffered a rather unglamorous fate as the 1950s gave way to the 1960s. By then the railroad was experiencing declining ridership all across its systems, and regional dayliners saw particularly sharp losses (only the Dakota 400 provided sleepers).

Timetable (July 16, 1969)

| Time/Leave (Train #1) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:00 PM | 0.0 | 8:55 AM | |

| 8.6 | 8:38 AM | ||

| 24.9 | |||

| 5:42 PM | 35.5 | 8:10 AM | |

| 6:12 PM | 58.3 | 7:35 AM | |

| 6:34 PM | 74.8 | 7:10 AM | |

| 7:02 PM | 97.9 | 6:40 AM | |

| 7:20 PM | 109.5 | 6:26 AM | |

| 7:37 PM | 123.8 | 6:10 AM | |

| 8:00 PM | 137.1 | 5:55 AM |

Final Years

In an effort to curb rising costs the C&NW ended or reduced services where possible. For instance, in Wisconsin the railroad was able to eliminate 14 secondary trains by introducing bi-level, gallery cars but even this effort was only a short-term solution that wasn't able to stop the public from fleeing the rails for automobiles and airlines.

After the Katy lost its name the 'North Western dropped the 400 designation altogether during the late 1960s referring to its trains thereafter as merely "Streamliners" and marketing itself as the "Route Of The Streamliner."

When Amtrak began service the railroad had only a few scheduled trains still running reaching such locations as Green Bay, Clinton, Milwaukee, northern Wisconsin, and Michigan's Upper Peninsula (this, of course, did not include suburban Chicago commuter service).

Recent Articles

-

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad. -

Delaware Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:23 PM

Delaware may rank 49th in state size but has a long history with trains. Today, a few museums dot the region. -

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here.