Chesapeake and Ohio Railway: Map, Logo, History

Last revised: November 9, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was one of several Appalachian coal

haulers and is perhaps best remembered for its marketing sensation, Chessie the sleeping kitten, as well as its buyout of the Baltimore

& Ohio during the early 1960s.

An icon even outside the rail industry, many people today still recognize the kitten and its association with railroading in some way. The C&O's earliest history traces back the early 19th century when Virginia was first building railroads.

It gained its current name in the 1870s upon which time it grew into a coal-hauling juggernaut similar to the nearby Norfolk & Western.

In addition to excellent management throughout much of the 20th century, the company earned substantial profits even during the industry's turbulent years of the 1960s and '70s.

It thrived on West Virginia and Kentucky coal and was a gateway between Chicago and the ports of Virginia. Today, much of the remaining C&O network is operated by CSX Transportation.

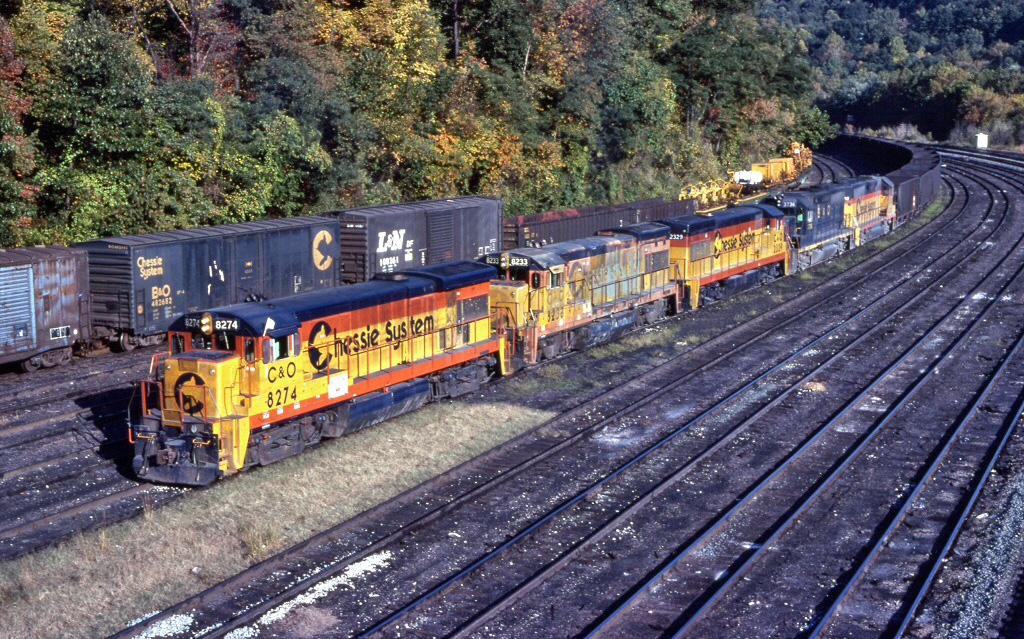

Photos

Chessie System/C&O B30-7 #8274 leads empties westbound through the yard at Clifton Forge, Virginia in October, 1983. Rob Kitchen photo.

Chessie System/C&O B30-7 #8274 leads empties westbound through the yard at Clifton Forge, Virginia in October, 1983. Rob Kitchen photo.History

While the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway of the 20th century was a highly profitable and successful operation it took many years before reaching that plateau.

The road's ancestry can be traced all of the way back to the James River Company, a canal operation which opened in 1790 between Richmond and Westham, Virginia. It later became the James River & Kanawha Canal. Unfortunately, by the time of its renaming canal transportation was fast being replaced by the much more efficient railroad.

The C&O's earliest such predecessor was the Louisa Railroad, incorporated on February 18, 1836 by the Virginia General Assembly to open a 22-mile route from Frederick's Hall to Taylorsville (today, known as Doswell) where a connection was established with the north-to-south Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad.

From the start, the system had a relatively strong financial backing and wasted no time completing its charter, opening in December of 1837.

At A Glance

2,730.29 (1930) 5,343 (1950) |

|

Chicago - Cincinnati, Ohio - Ashland, Kentucky - Staunton, Virginia - Newport News, Virginia Gordonsville, Virginia - Washington, D.C.Clifton Forge - Richmond, VirginiaAshland - Louisville, KentuckyAshland, Kentucky - Columbus, Ohio - Toledo, OhioColumbus - Pomeroy, OhioCatlettsburg, Kentucky - Elkhorn City, KentuckyRonceverte - Durbin/Bartow, West Virginia (Greenbrier Branch)Chicago - Grand Rapids, Michigan - Detroit - St. Thomas, Ontario - Buffalo/Niagara Falls, New York (ex-Pere Marquette)Grand Rapids - Petoskey/Bay View, MichiganErieau, Ontario - Ludington, MichiganLudington - Milwaukee/Manitowoc/Kewaunee, Wisconsin (car ferry service)Toledo - Bay City, MichiganPort Huron - Bay City - Elmdale, MichiganHolland - Muskegon - Hart, Michigan | |

Freight Cars: 92,992 Passenger Cars: 324 | |

The Virginia Commonwealth of the early 19th century was a forward-thinking state and a big proponent of railroads, realizing their potential in opening trade and economic opportunities not only within its own borders but also beyond.

Its Piedmont region could support diverse types of agriculture, which persists through today, and the Louisa was utilized by farmers to ship their products to market. In 1850 the company was renamed the Virginia Central as its promoters eyed expansion across the state and even further west.

Logo

According to Thomas Dixon, Jr.'s, "Chesapeake & Ohio Railway: A Concise History And Fact Book," the road's ultimate goal was to reach the Shenandoah Valley and what is today the state of West Virginia (then Western Virginia).

It also saw the potential in a direct link to Richmond, despite protestations from the RF&P, which now viewed the VC as a rival. The RF&P's efforts were in vain as the VC reached the state capital the same year it acquired its new name.

In 1857 the VC had expanded as far westward as Jackson's River Station near present-day Clifton Forge via Gordonsville, Charlottesville, and Staunton offering it a network of around 192 miles.

Even before the Louisa Railroad had been renamed the state stepped in to assist its future westward extension by chartering the Blue Ridge Railroad in 1849 to tackle the Blue Ridge Mountains.

This line's most impressive engineering feature was the Blue Ridge Tunnel (also known as the Crozet Tunnel) designed by engineer Claudius Crozet. It was located at Rockfish Gap and spanned 4,237 feet, opening for service in 1858.

The bore became an Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and remained in use until 1942 when the C&O opened a new tunnel to replace the original.

The Blue Ridge Railroad was leased by the VC in 1858 as it looked to finally reach Covington. Unfortunately, the Civil War broke out in 1861 and further construction ceased.

The Virginia Central was a vital asset for the Confederacy during the conflict but was heavily damaged by both sides. After hostilities ended in May of 1865 crews needed until July 23rd to get the road back in service.

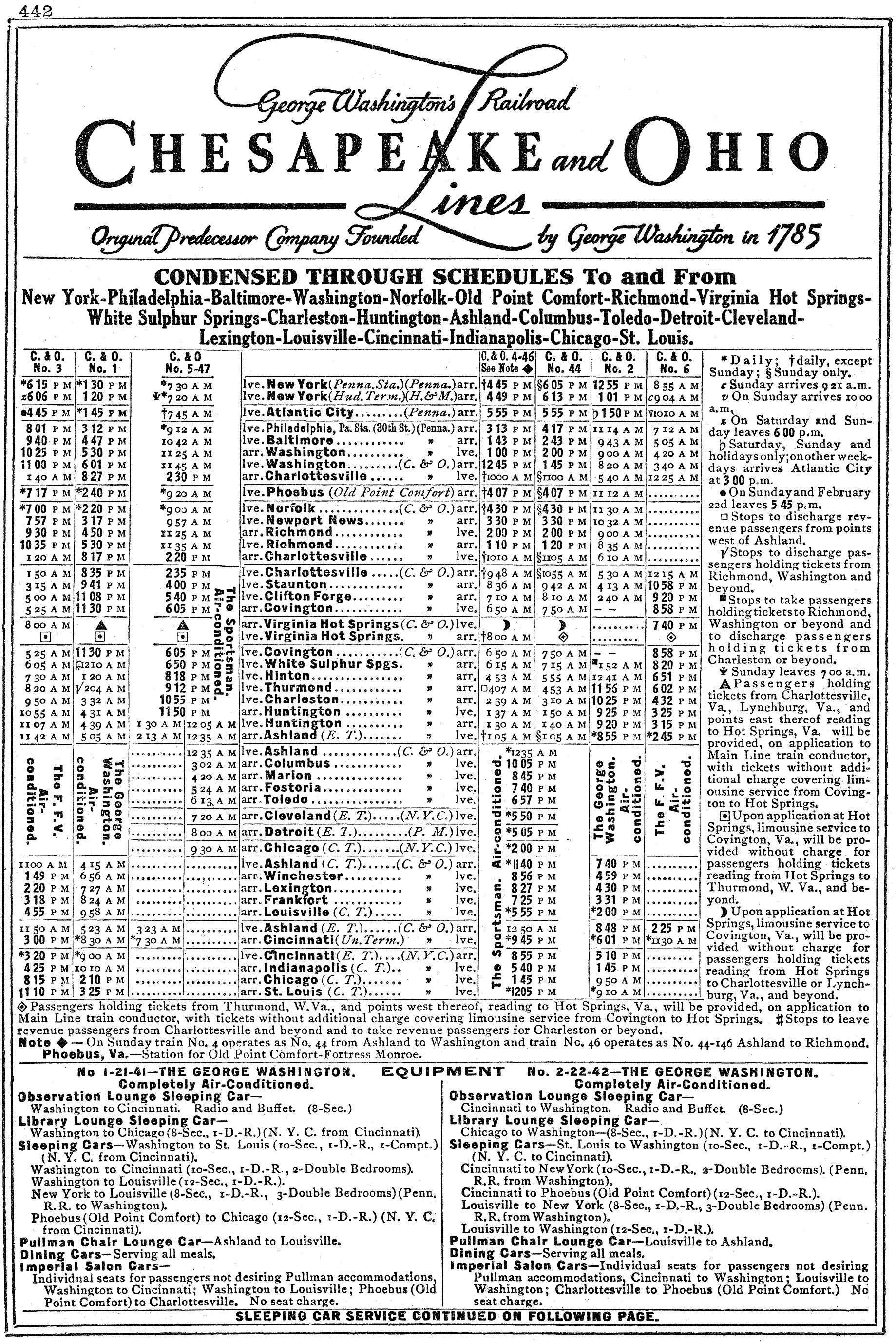

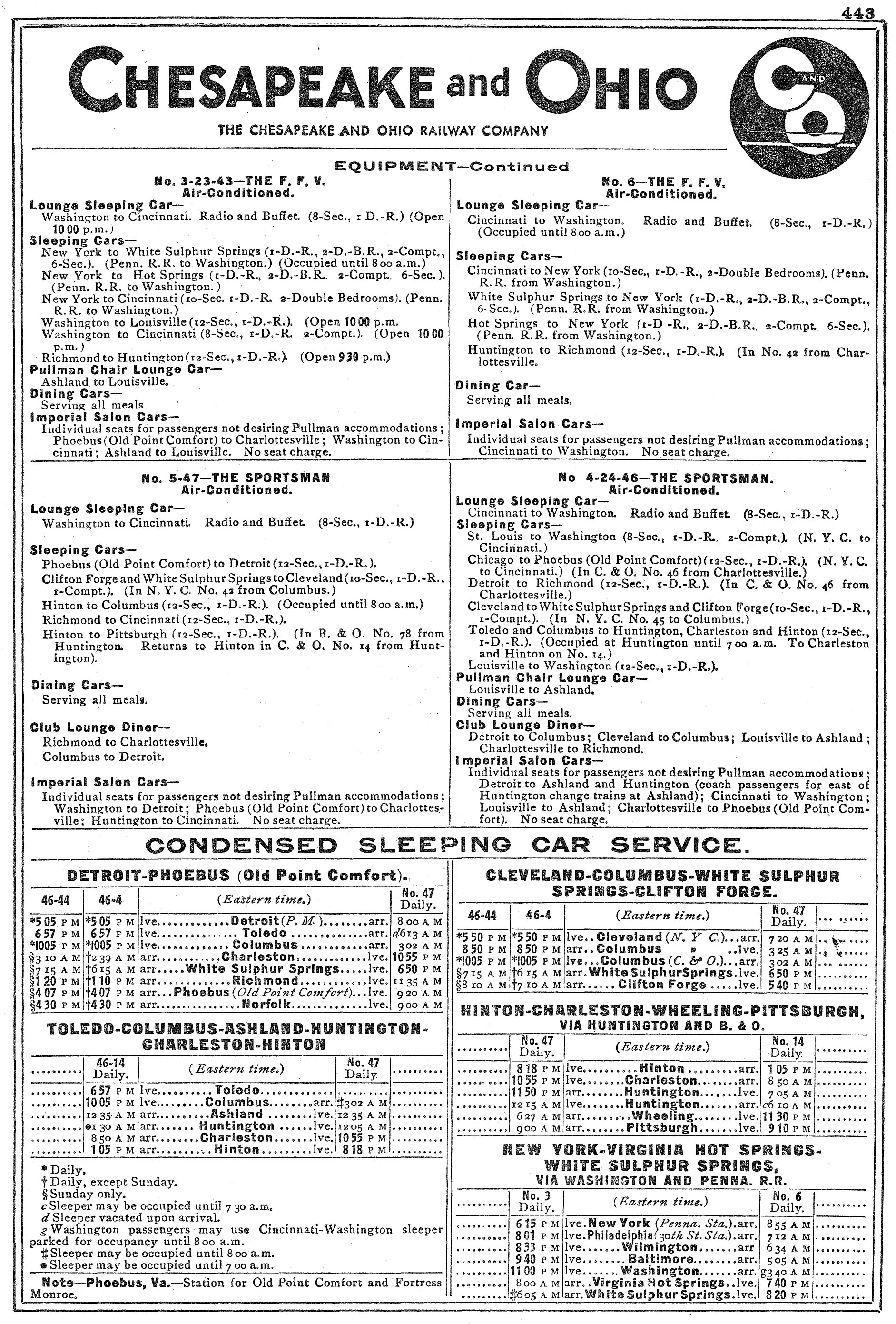

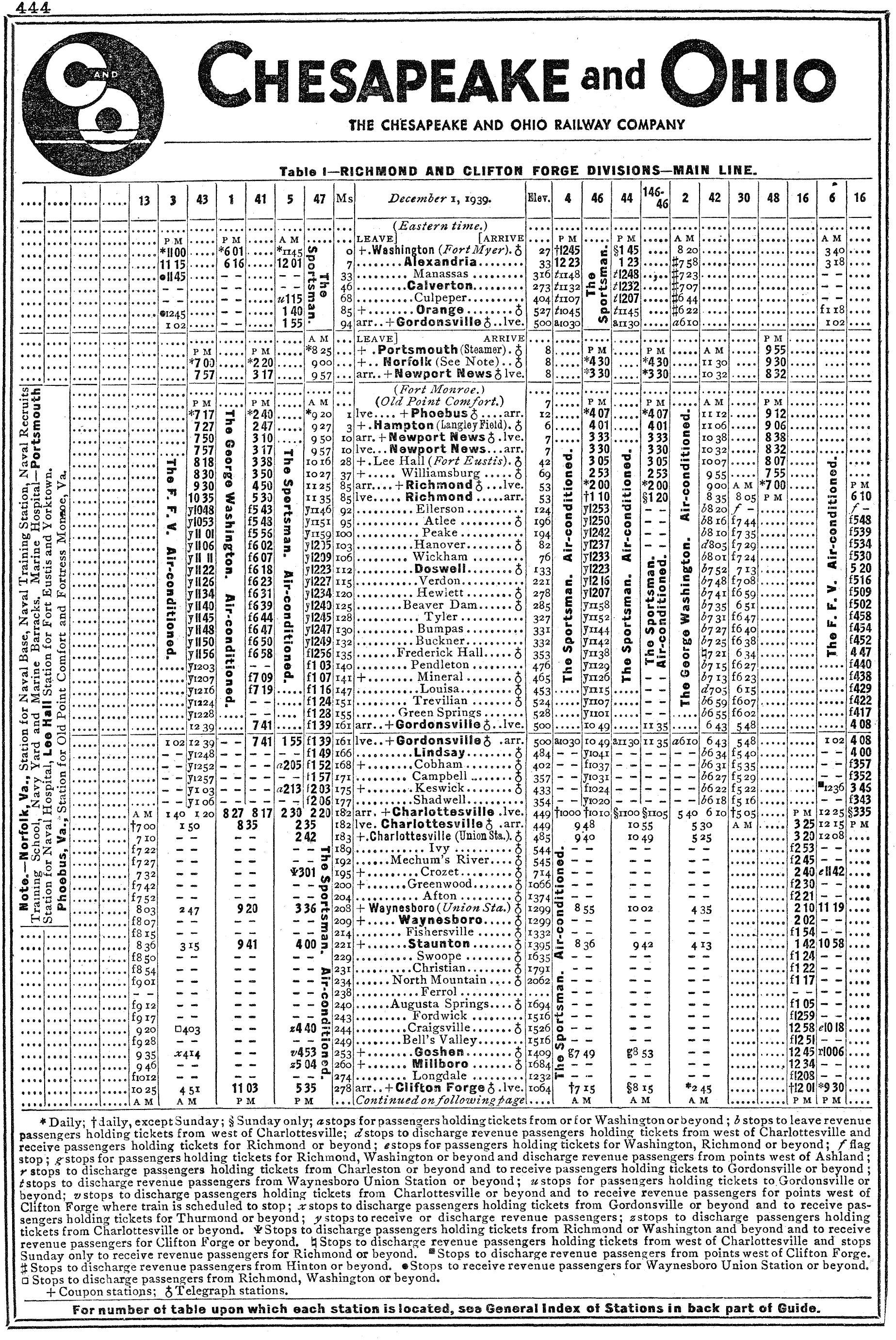

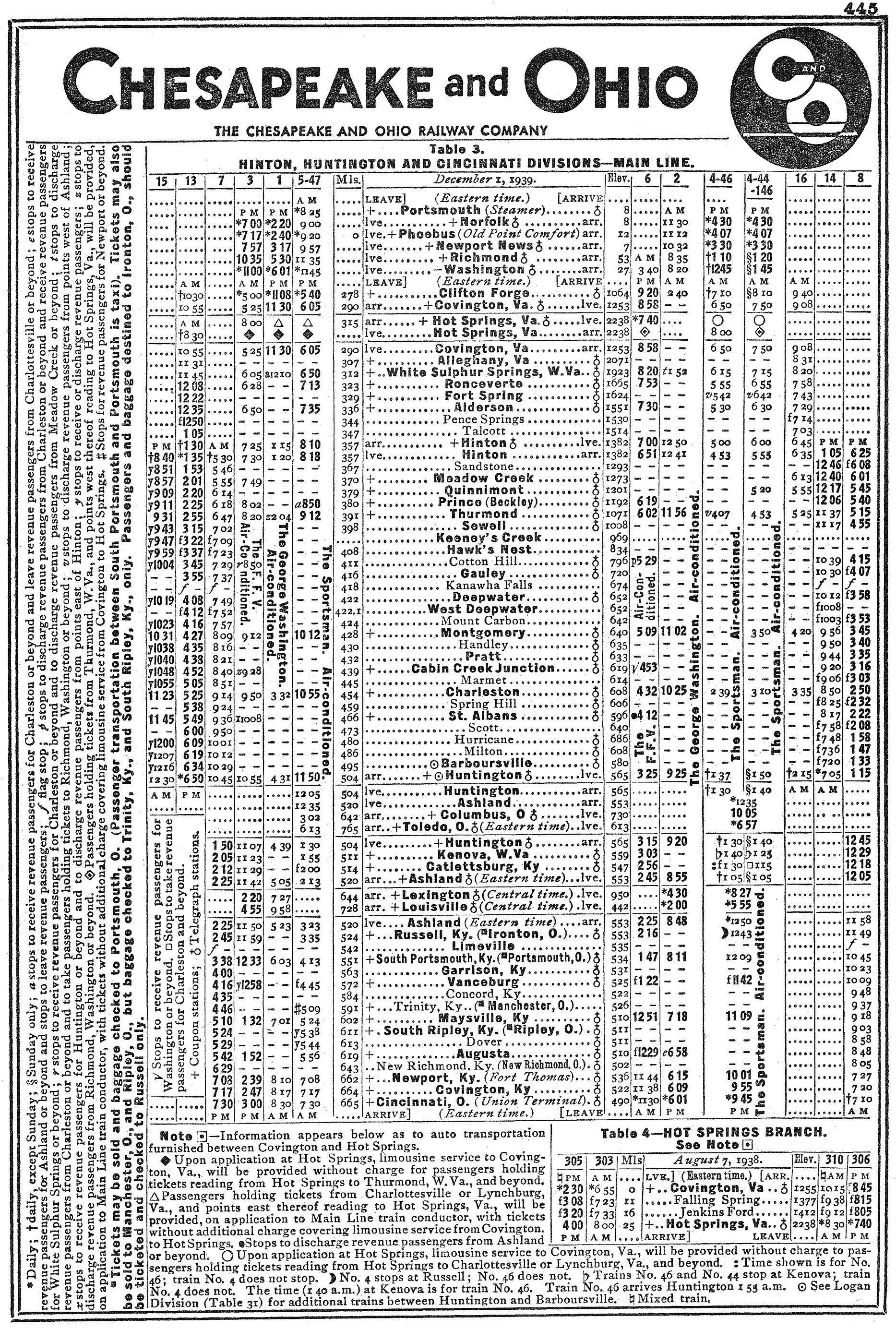

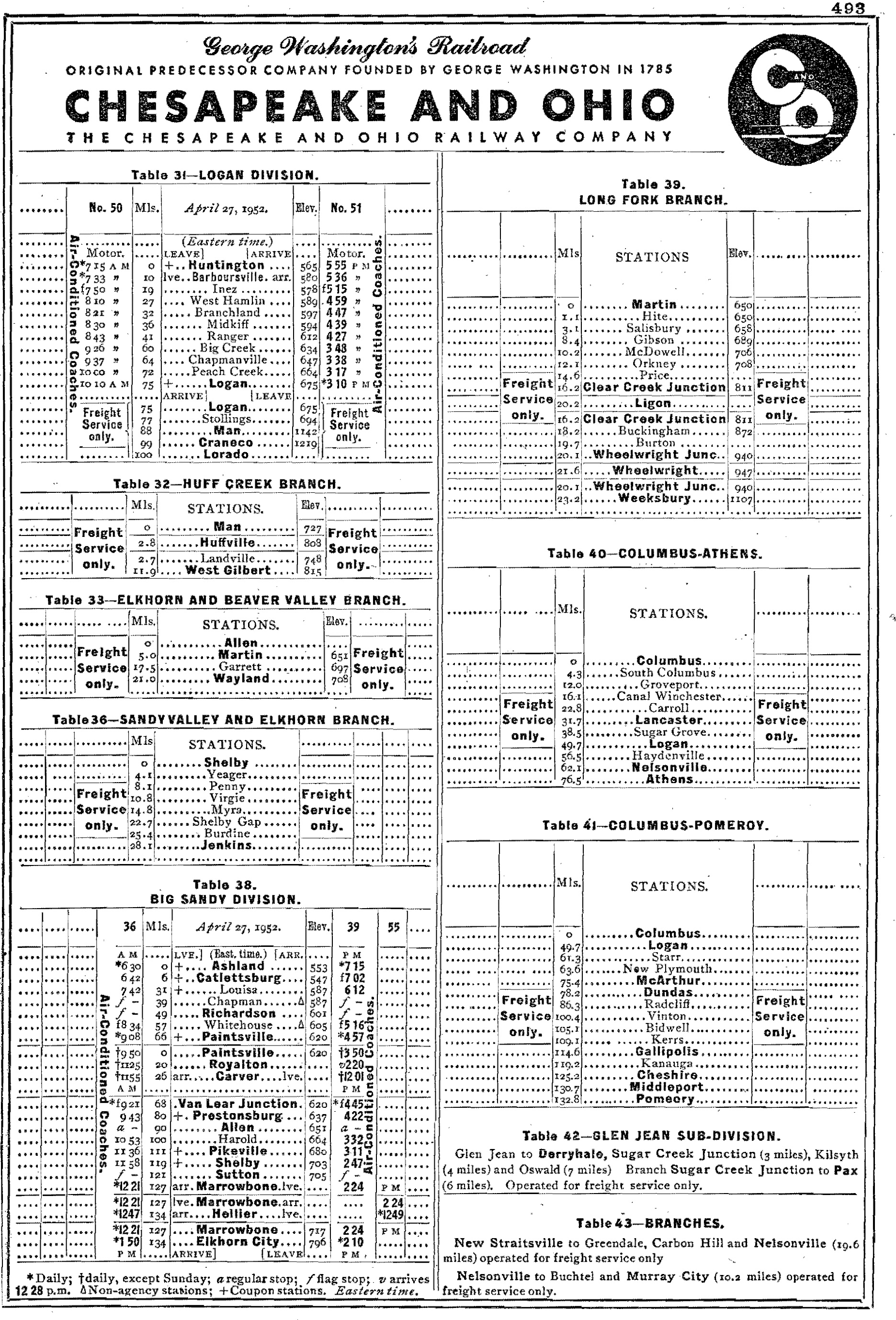

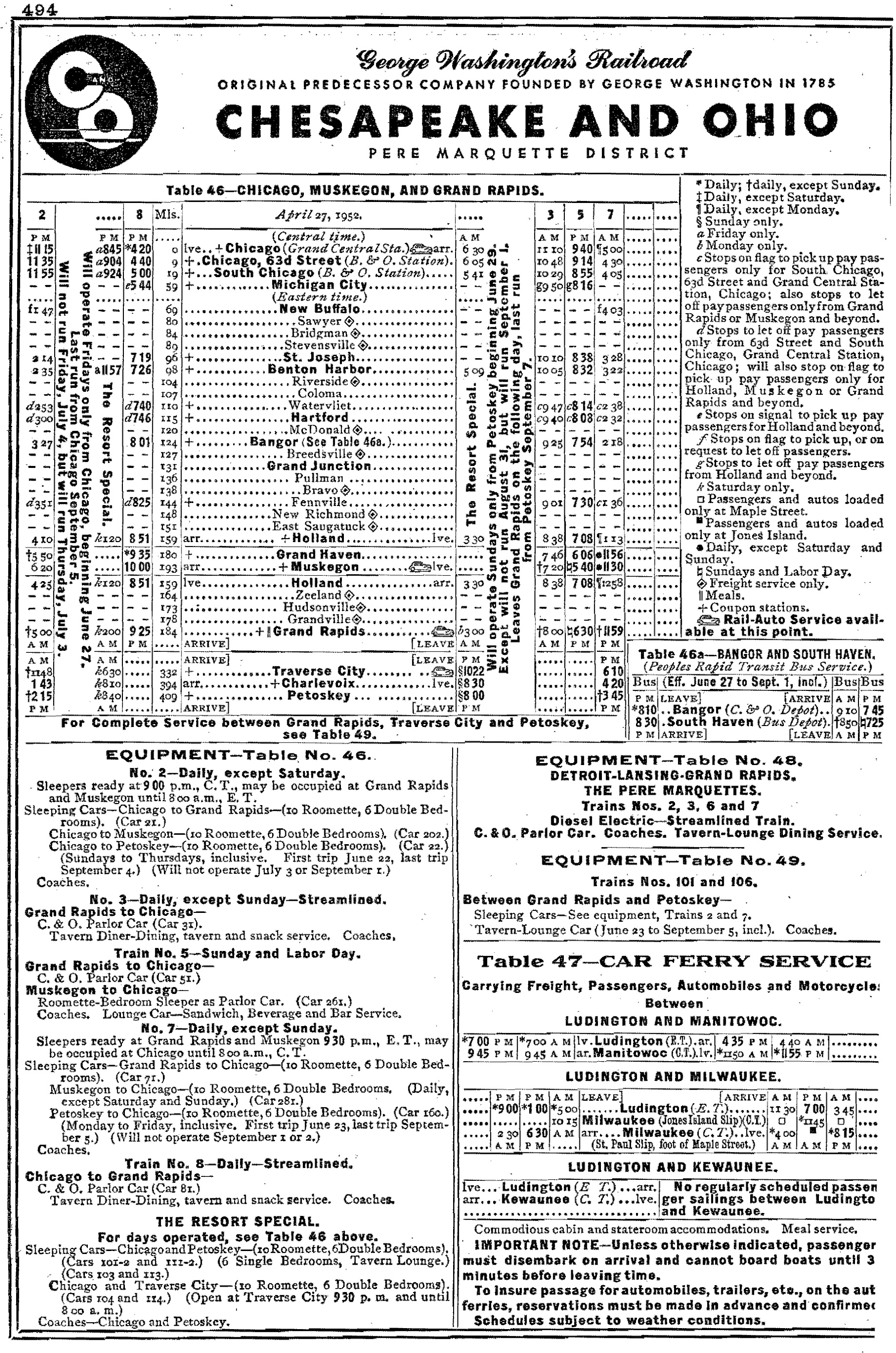

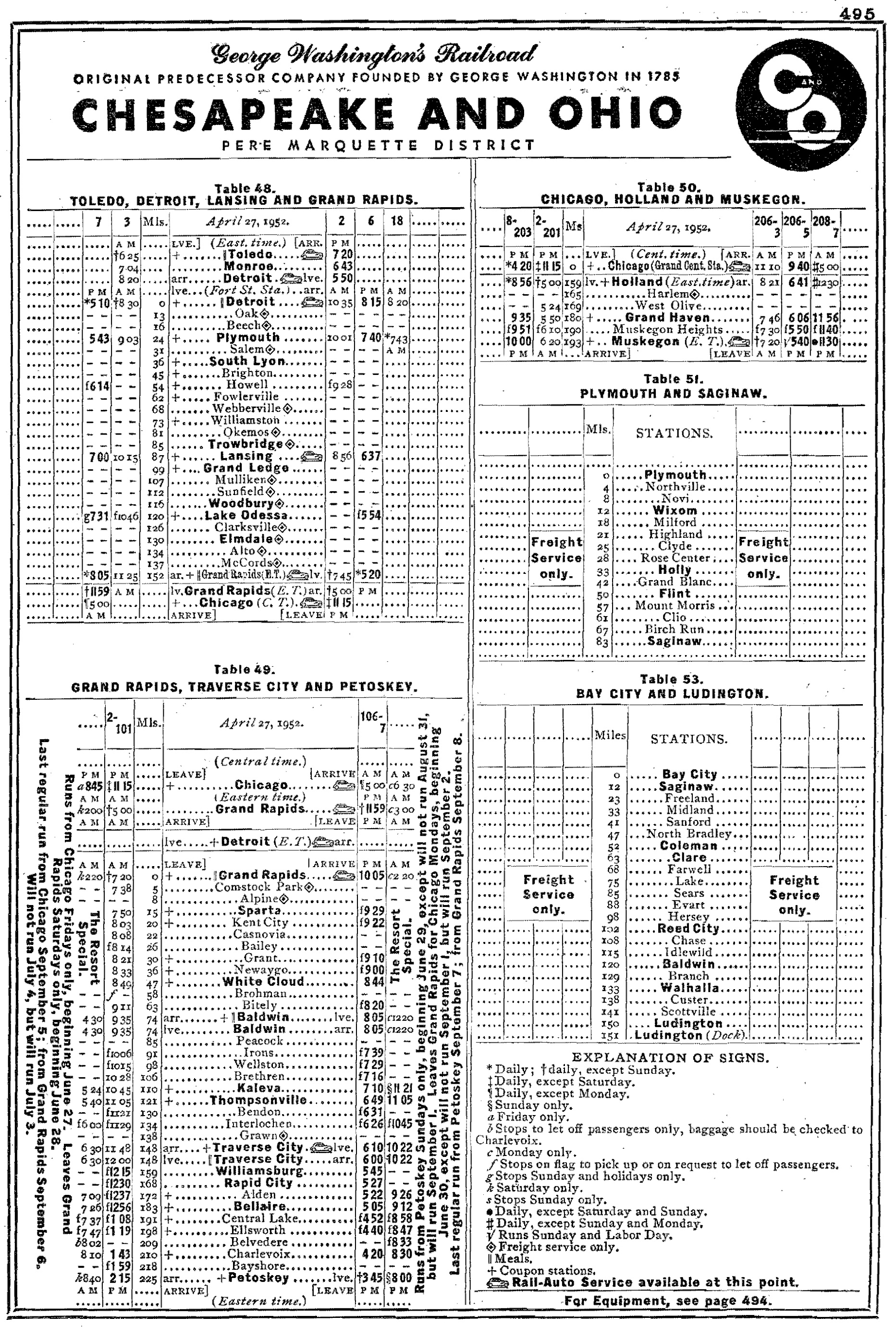

Timetables (1940)

On July 1, 1867 the VC finally reached Covington although the war's devastation meant funds were exhausted to continue further construction.

Its only other growth during this time was acquiring the assets of the Covington & Ohio, which had partially completed a route to the Ohio River along a stage-coach line originally surveyed by the James River & Kanawha Canal.

In 1868 the Virginia Central was renamed as the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company to further clarify its intentions of reaching the Ohio River and Chesapeake Bay.

Enter Collis Huntington, who is best remembered for his work in building the western leg of the Transcontinental Railroad. In 1869, just after this project was completed, Huntington pumped new life into the C&O by funding its push towards the west.

The railroad followed the Covington & Ohio's routing, reaching Ronceverte along the banks of the Greenbrier River before turning north from Hinton. This town lay within the beautiful New River Gorge and rails snaked their way along the waterway until reaching Gauley Bridge where it became the Kanawha River.

Why, "George Washington's Railroad?"

It is interesting the Chesapeake & Ohio chose to carry a slogan, "George Washington's Railroad" when our nation's first president had no direct ties to the company and died more than three-decades before its first predecessor was ever chartered.

It all began with the James River Company, envisioned by Washington in 1785 as an efficient transportation artery to connect eastern and western Virginia at the Ohio River.

He planned the canal system himself, using the James River across much of the state's eastern and central regions before picking up others, such as the Kanawha and New Rivers, to reach the Ohio.

It opened its first seven miles between Richmond and Westham, Virginia in 1790. It was built no further during Washington's life but did see a bit of commercial traffic until its acquisition by the state in 1820.

In 1835 it was reincorporated as the James River & Kanawha Canal Company, reaching Buchanan by 1851. This proved the extent of its network due to increasing competition from the railroad.

Before the Chesapeake & Ohio and Baltimore & Ohio merged the two interchanged at Kenova, West Virginia near Huntington where the former's main line met the latter's Ohio River Branch. Here, B&O steamers can be seen to the left while C&O GP9's hustle a coal drag in a scene that probably dates to the 1950s. Author's collection.

Before the Chesapeake & Ohio and Baltimore & Ohio merged the two interchanged at Kenova, West Virginia near Huntington where the former's main line met the latter's Ohio River Branch. Here, B&O steamers can be seen to the left while C&O GP9's hustle a coal drag in a scene that probably dates to the 1950s. Author's collection.In 1878 the right-of-way was sold to the new Richmond & Alleghany Railroad, which began construction in 1880 along the canal's old towpath.

According to Laura Armitage's article, "Richmond & Alleghany Railroad," it completed a 230.31-mile route between the Chesapeake & Ohio at Richmond to Clifton Forge in 1881, as well as a 19.38-mile branch to Lexington via Balcony Falls.

The company fell into receivership in 1883 and emerged on May 20, 1889 as the Richmond & Alleghany Railway, upon which time it was acquired by the C&O (the company purchased it outright on January 20, 1890).

The Chessie had been eyeing a more direct line across the state and got it in the R&A's low-grade route, making it ideal to handle heavy tonnage such as coal.

In addition, the route's canal history and ties to Washington allowed the C&O, albeit somewhat indirectly, to claim a heritage to our nation's first president. Today, the corridor remains heavily used by CSX Transportation.

The route continued its way into Charleston, the future capital of West Virginia, before turning away near St. Albans and terminating at the Ohio River near the mouth of the Big Sandy River. The latter location became the town of Huntington, named for the tycoon, himself.

It would eventually become the location of the railroad's major locomotive maintenance and repair shops. The C&O was officially completed at Hawk's Nest, West Virginia along the New River Gorge on January 29, 1873.

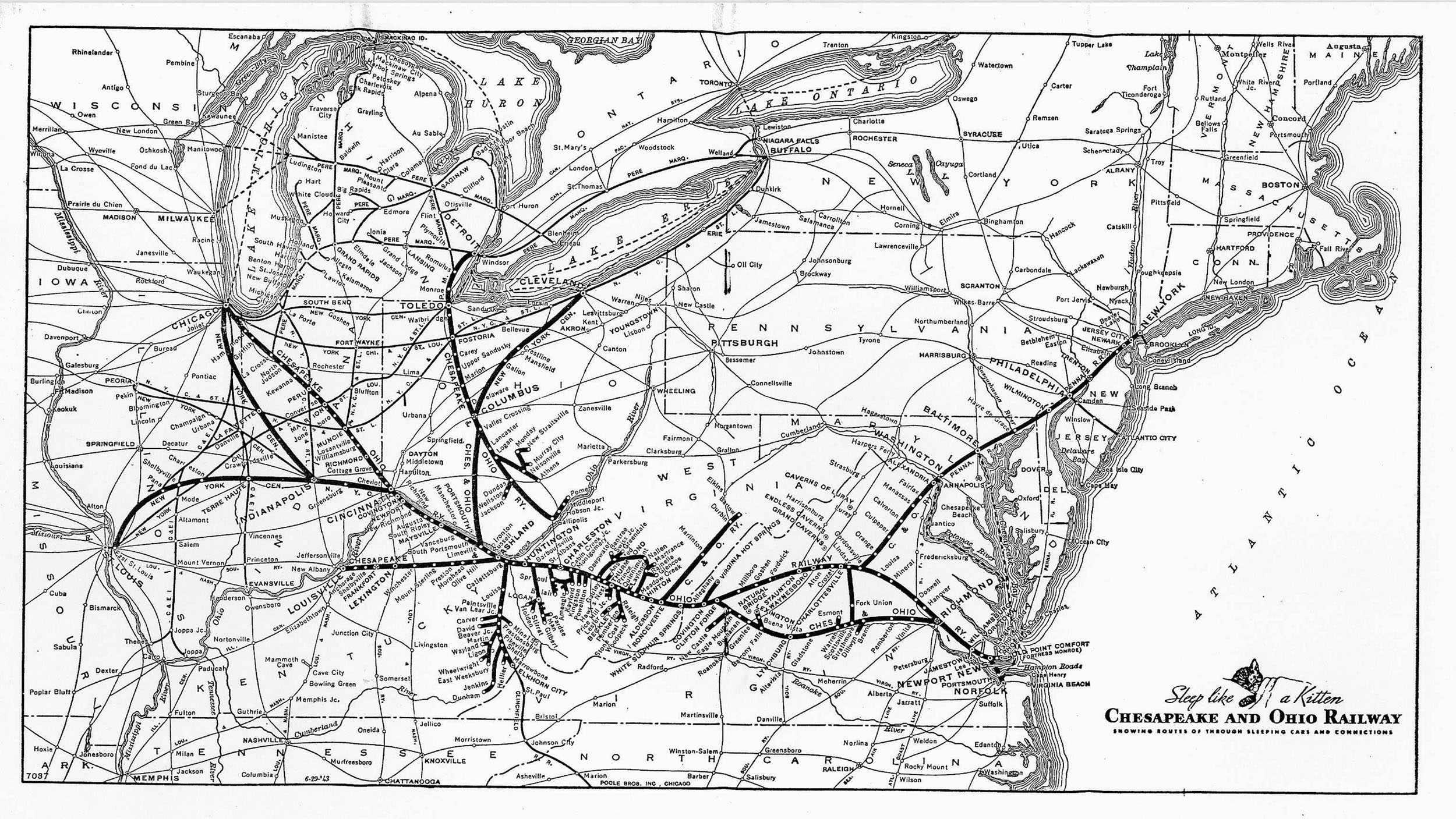

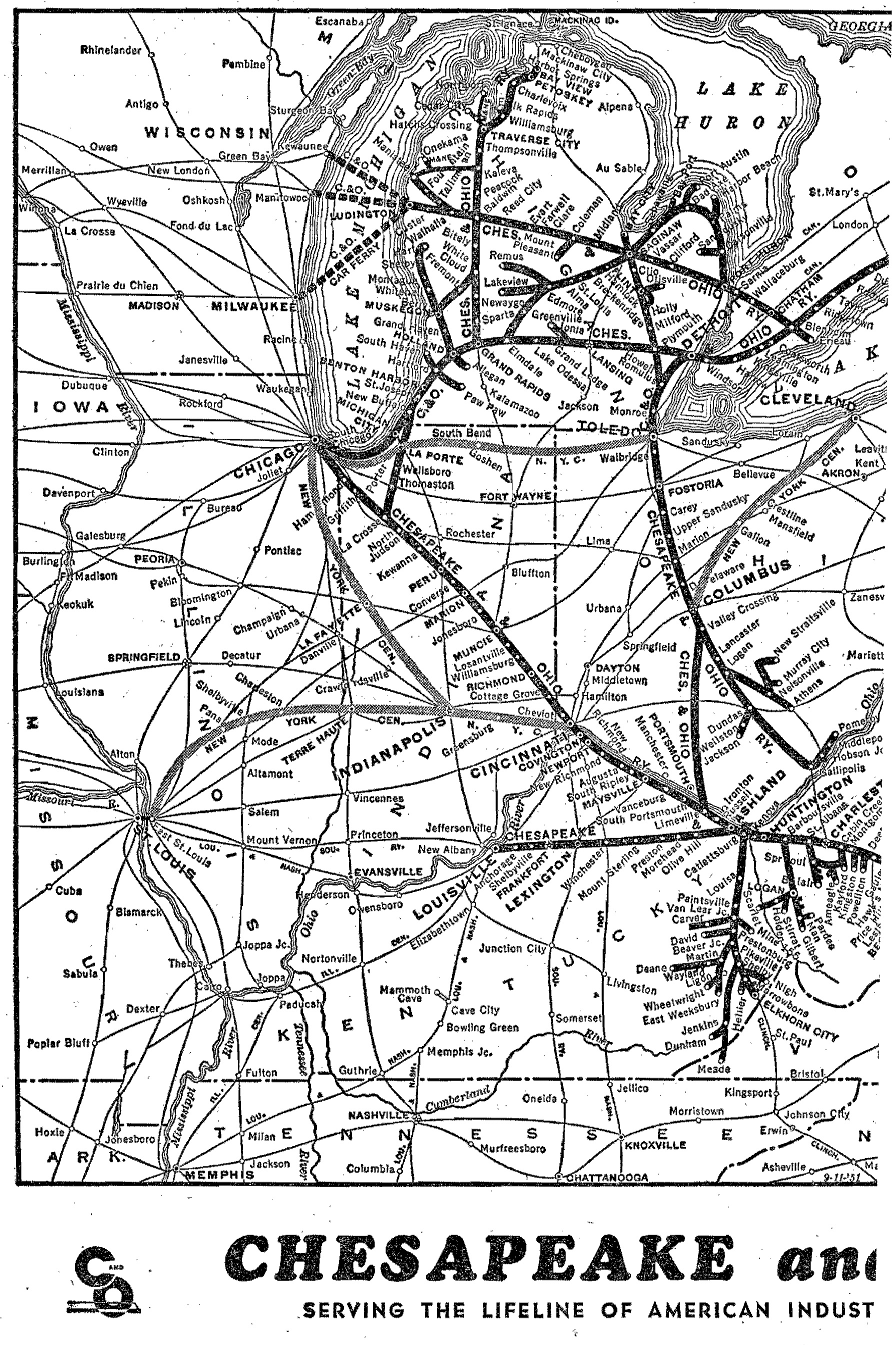

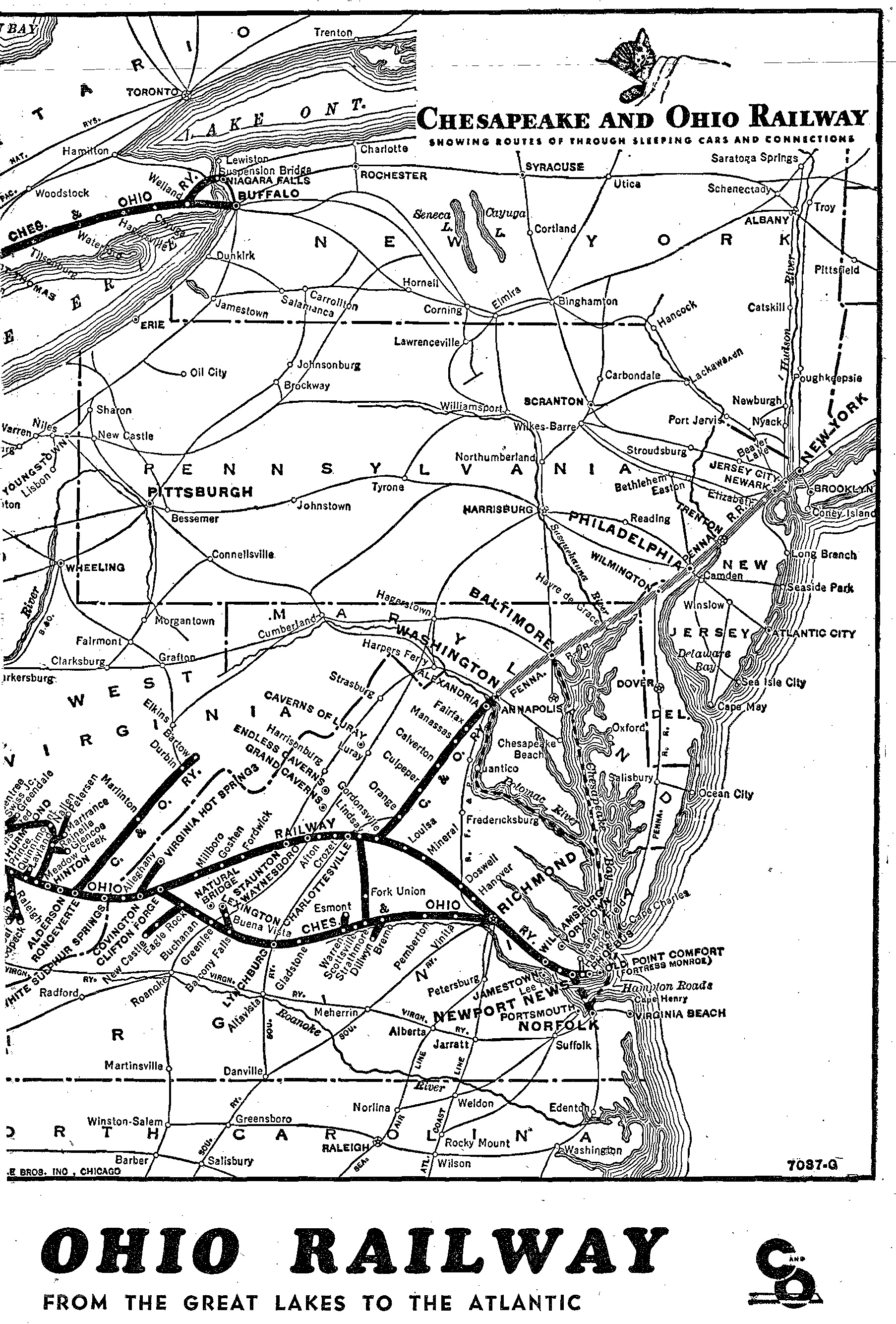

System Map (1946)

Unfortunately, that year coincided with a severe recession as a result of a financial panic and the C&O struggled to remain solvent. Huntington had intended to use the railroad as a means of piecing together a true transcontinental railroad but the economic downturn was too great and the C&O fell into receivership in 1878.

It was soon reorganized as the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, setting the stage for what became a highly profitable system. During June of 1879, Huntington formed the Newport News & Mississippi Valley to complete a through route from Ashland to Lexington, Kentucky.

The NN&MV ran from the C&O at Mount Savage (about 25 miles southwest of Ashland) to a connection with the Elizabethtown, Lexington & Big Sandy Railroad at Mt. Sterling. The EL&BS continued on into Lexington and was acquired by Huntington.

Through service between Ashland and Lexington commenced during December of 1881 while trackage rights over the Louisville & Nashville enabled the C&O to reach Louisville. That same year the C&O pushed rails eastward into Newport News, finally providing it an east coast port.

Huntington had managed to maintain control of the railroad, even after its bankruptcy, until 1888 when, according to Mike Schafer's, "More Classic American Railroads," he lost out to Cornelius Vanderbilt (of New York Central fame) and J.P. Morgan.

A new ownership was for the best; while Huntington had funded the C&O's continued expansion he had spent little on upgrading the company to modern standards. A new management team did just that and by the turn of the 20th century it was poised to be a very successful enterprise.

In the meantime, it spent the rest of the century continuing to grow with a near-limitless cash flow. On December 25, 1888 the C&O opened service to Cincinnati, Ohio following the southern bank of the Ohio River via Ashland, Augusta, and Covington, Kentucky.

It blossomed into a major coal carrier at this time, adding branches across southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky (here, an important connection was also made with the Clinchfield Railroad at Elkhorn City) to tap new mines, a process that continued through 1920. The road spent heavily to improve bridges, update tunnels, and position itself to handle the increased traffic demands for years to come.

It constructed shop and/or yard complexes in Charlottesville, Gladstone, and Clifton Forge, Virginia; Handley, West Virginia; and Russell, Kentucky. In 1891 the C&O obtained trackage rights over the Virginia Midland Railroad between Orange and Washington, D.C. which provided a key connection to the nation's capital.

The VMRR would soon become a subsidiary of the new Southern Railway system. Much of the C&O's growth during the 20th century through acquisition and not new construction.

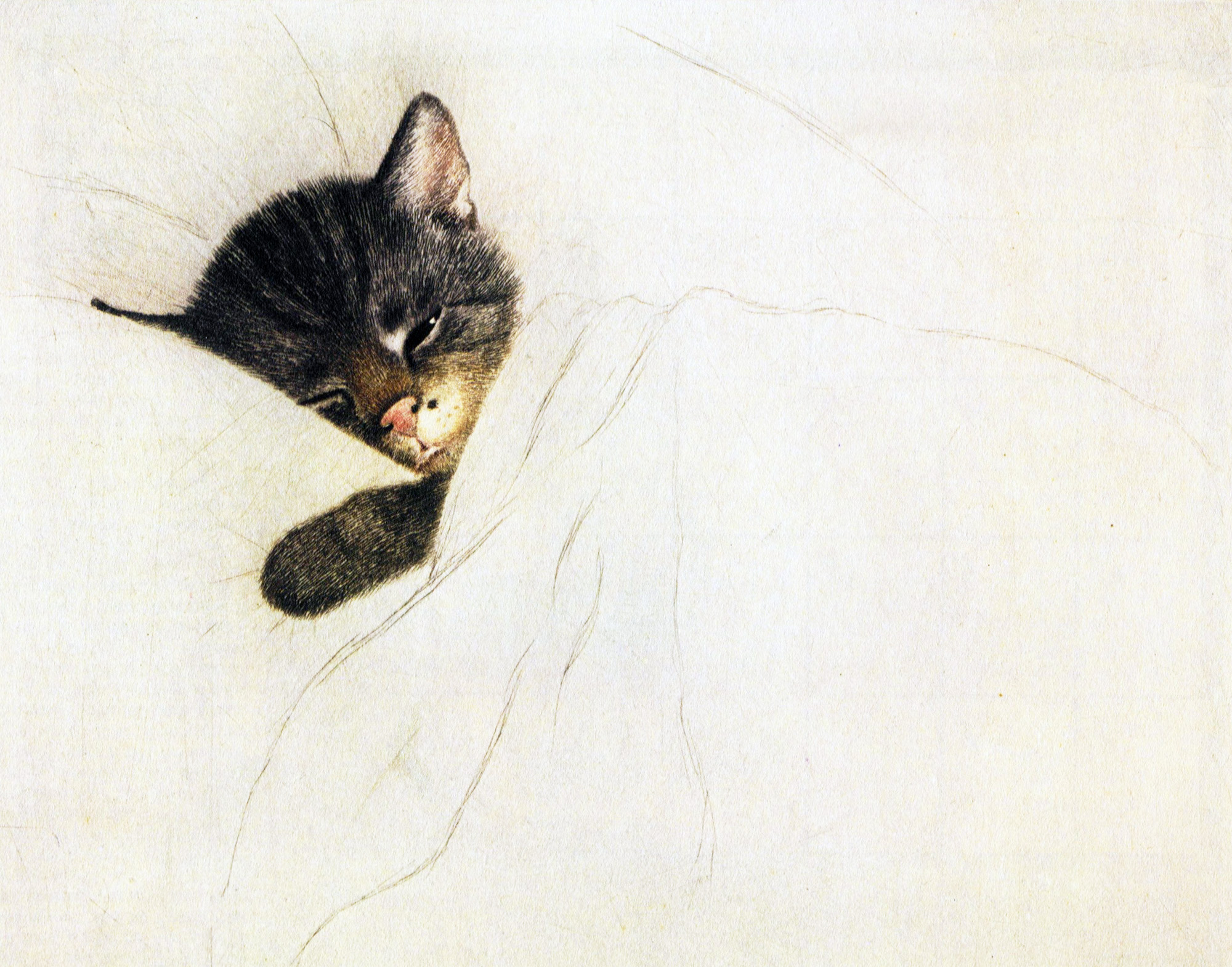

Chessie, The Famous Kitten

The creator of the sleeping kitten image was an artist by the name of Guido Grenewald who had created the cute feline to promote animal kindness.

In 1933, Lionel Probert, who headed the C&O's public relations and marketing department, saw Grenewald's piece and was instantly drawn to its potential. At the time, Probert was looking for a way to showcase the railroad's new air-conditioned sleeping cars while also revitalizing sagging patronage.

He purchased Grenewald's rendering for $5, came up with the name Chessie (named after the railroad), and added the slogan, "Sleep Like A Kitten And Wake Up Fresh As A Daisy In Air-Conditioned Comfort."

The first advertisement appeared in Fortune Magazine's September, 1933 issue and was an instant success. By 1934, Chessie, had appeared in more than 40,000 pieces of media, from newspapers to calendars.

The company's passenger traffic soared and the advertising campaign remains one of the most successful of all time; even today the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Historical Society continues to sell calendars and other memorabilia featuring Chessie (when the kitten debuted demand was so high that the C&O could not keep merchandise in stock).

The kitten's success resulted in two additional mascots joining it, named Nip and Tuck, as well as a father cat named Peake. The three additional felines continued to appear in advertisements through 1948.

Of course, Chessie’s celebrity status did not end with merchandise and advertising, the kitten became synonymous with the C&O; her celebrity was reignited in the early 1970s when the Chessie System, a holding company for the C&O, B&O, and Western Maryland, overlaid the kitten’s silhouette in the Chessie System "C" adorning the railroads new vermilion, yellow, and blue livery.

The C&O eyed a connection to Chicago as traffic surged and found it in the Chicago Cincinnati & Louisville Railroad. The CC&L had entered receivership in 1908 and was acquired by the C&O on June 23.

This road, covering 284.5 miles between Cincinnati and Hammond, Indiana, gave Chessie direct access into the Windy City thanks to friendly trackage rights with other lines.

The CC&L, which became the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway of Indiana, ran via Richmond, Muncie, and Peru cutting diagonally across the state. It allowed coal and the C&O's other diverse freight to flow both east and west while reaching the most important gateway in the country in the process.

Chesapeake & Ohio steam turbine #500 (M-1) during its trials in 1947. The locomotive was meant to power the streamliner "Chessie," ultimately never launched, in an attempt to prove that advancements in steam technology could still compete against the diesel. It was just over 140 feet in length with a top speed of 100 mph. Unfortunately, Baldwin, Westinghouse, and C&O engineers could never work out the numerous troubleshooting issues and gave up on the design.

Chesapeake & Ohio steam turbine #500 (M-1) during its trials in 1947. The locomotive was meant to power the streamliner "Chessie," ultimately never launched, in an attempt to prove that advancements in steam technology could still compete against the diesel. It was just over 140 feet in length with a top speed of 100 mph. Unfortunately, Baldwin, Westinghouse, and C&O engineers could never work out the numerous troubleshooting issues and gave up on the design.Looking beyond Chicago the company's leadership worked its way further into the Midwest; also in 1910 it acquired the Hocking Valley Railway, which stretched from Toledo to Athens, Jackson, Gallipolis, and Pomeroy, Ohio via Columbus.

At first the C&O required trackage rights over the Norfolk & Western to reach this disconnected subsidiary via Limeville, Kentucky and Valley Crossing, Ohio.

However, by 1927 it had completed its own connection and now had a through route across the Buckeye State (the railroad formally merged the HV into its network in 1930).

Passenger Trains

Fast Flying Virginian/F.F.V.: (Washington/Newport News - Cincinnati/Louisville)

George Washington: (Washington/Newport News - Cincinnati/Louisville)

The Chessie (Never Launched): (Washington - Cincinnati)

Pere Marquette: (Detroit-Grand Rapids, Chicago-Grand Rapids/Muskegon, and Detroit-Saginaw)

Resort Special: Originally served Chicago and Petoskey but later connected Washington with White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

Sportsman: (Washington/Newport News - Cincinnati/Detroit)

During the mid-1920s the C&O was acquired by the Van Sweringen brothers of Cleveland, Ohio who expanded its reach into Michigan and as far east as Buffalo, via Ontario, Canada, thanks to control of the Pere Marquette. It also maintained authority over the Nickel Plate Road for many years.

Following the Great Depression Chessie's success only increased: sustained by strong coal earnings it weathered the 1930s rather easily, a decade which saw the birth of Chessie, a marketing sensation.

Throughout the rest of the C&O’s life it would earn healthy profits and in the early 1960s won a bidding war with the New York Central for control of its much larger northern neighbor, the Baltimore & Ohio.

The merger was approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission on December 31, 1962. However, rather than merge the B&O out of existence the railroad chose to gradually combine the two, slowly merging departments and other management areas.

This was done for several reasons but two of the most important was to placate the extremely loyal B&O employees (which would not take outright control and dissolution easily) and retain the its tax exempt status within the State of Maryland.

Chessie System

In 1972 came the largest change for the three railroads (including the B&O-controlled Western Maryland) when a new holding company was created, the Chessie System. Its new livery with the Chess-"C" was an instant hit and remains one of the most colorful, popular, and dynamic liveries ever applied to a locomotive.

The new Chessie System would become quite a juggernaut, earning substantial profits throughout the 1970s, one of only a handful to do so during a darkest days of the industry's history.

The Chessie System, however, would last a mere eight years as an independent company; in 1980 the Chessie roads and those of the Family Lines/Seaboard Coast Line Industries (which was a holding company for a number of southeastern railroads including the Seaboard Coast Line and Louisville & Nashville) formed CSX Corporation on November 1st.

Diesel Roster

Steam Roster

Class F (4-6-2)

Class J (4-8-2)

Class J3a/b (4-8-4)

Chesapeake & Ohio's second roster of "Super Power" engines was its fleet of 4-8-4 "Greenbriers." The first examples arrived from Lima in 1935 and railroad would eventually roster a fleet of twelve.

The company became quite fond of Lima's "Super Power" designs after acquiring forty 2-10-4s from the builder in 1929/1930. The C&O was so pleased with their performance many of its other late-era wheel arrangements - like the Greenbriers - were built by the Ohio manufacturer.

Chessie's 4-8-4s were powerful, graceful machines that often found themselves working passenger assignments in mountainous territory thanks to their high drivers and solid tractive effort. Today, one example from the class is preserved, J-3a #614. This fine locomotive became famous for leading excursions during the 1980s and 1990s.

It is perhaps best remembered for the ACE 3000 test trials in 1985 when then-Chessie System allowed Ross Rowland, the locomotive's owner, to test the viability of steam as a renewed source of main line power.

The big Greenbrier successfully lugged several loads of coal along the Chesapeake & Ohio main line between Huntington and Hinton that cold January day but the experiment ultimately failed to produce the desired results.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614 departs Parsons Yard in Columbus, Ohio with the "Chessie Safety Express" on May 17, 1981. The big 'Greenbrier' was bound for Russell, Kentucky that day. Roger Beighley photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 #614 departs Parsons Yard in Columbus, Ohio with the "Chessie Safety Express" on May 17, 1981. The big 'Greenbrier' was bound for Russell, Kentucky that day. Roger Beighley photo. American-Rails.com collection.Development

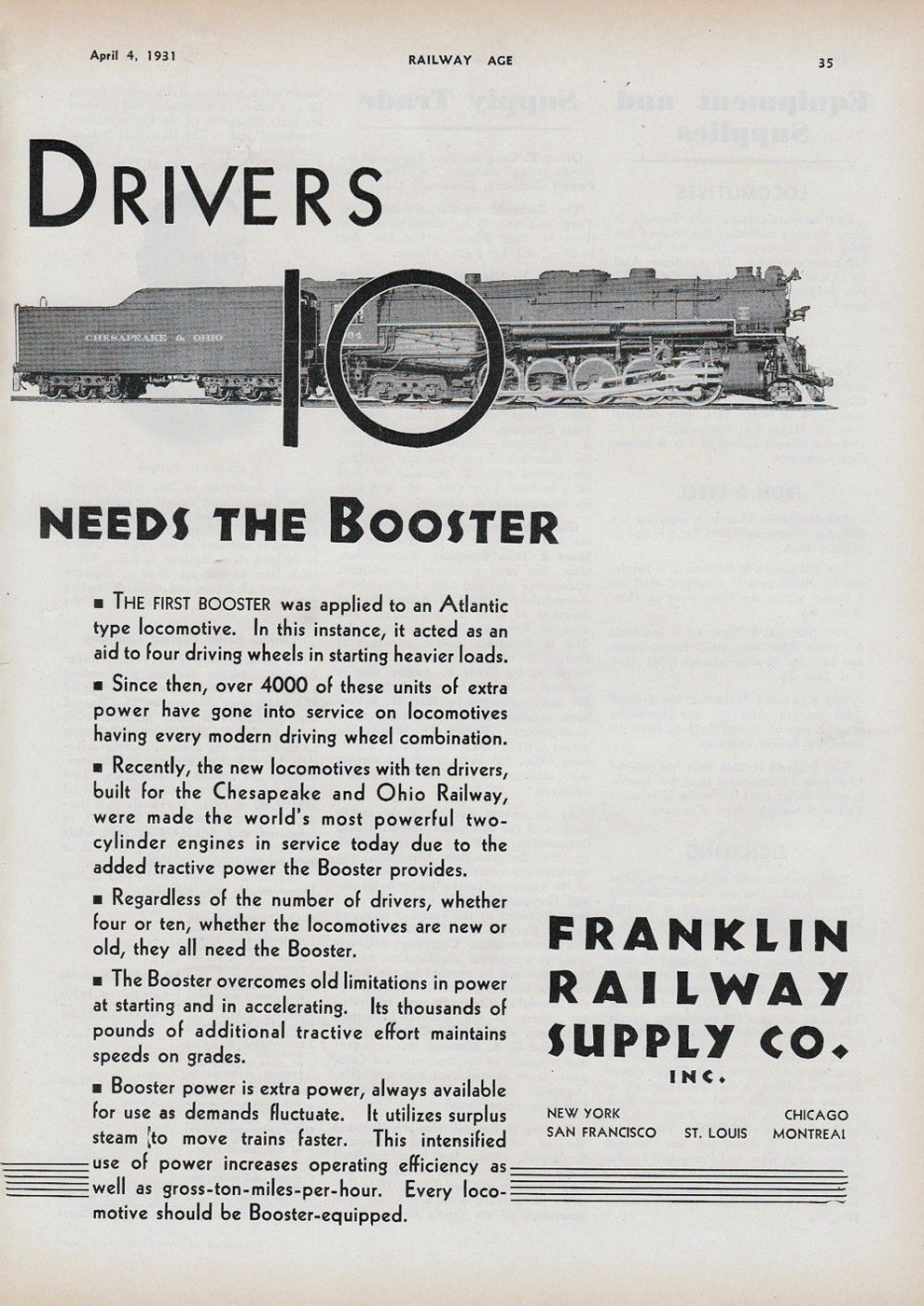

The C&O's first taste of Super Power steam came in 1929 when it placed an order with Lima Locomotive Works for a batch of forty new 2-10-4 "Texas" type locomotives.

These machines, numbered 3000-3039 and classed T-1, arrived in 1930 and were a culmination of testing carried out by the Advisory Mechanical Committee (AMC).

The AMC was an oversight body created in 1929 to improve and standardize steam designs across the Van Sweringen-owned properties which - along with the C&O - included the Erie, Nickel Plate Road, Hocking Valley Railway (a later C&O subsidiary) and Pere Marquette.

The T-1s were essentially enlarged 2-8-4. They utilized an additional driving axle and were patterned from Erie's Class S models which had first entered service in 1927. The 2-10-4's often found themselves handling 160-car heavy freights, usually coal, in the C&O's western territory between Russell, Kentucky and Toledo, Ohio.

The success of these locomotives immediately sold the railroad on the benefits of Super Power technology. As a result, virtually all of its future purchases were for such designs - and many came from Lima.

These included its 4-8-4s, all of which were outshopped by the Ohio manufacturer. By the mid-1930s the C&O was in need of larger, and more powerful designs, to handle passenger assignments on the rugged mountain grades between Charlottesville, Virginia and Hinton, West Virginia.

Through the AMC the new 4-8-4 was born, based from the earlier success of the 2-10-4s. The first arrived between December, 1935 and early January, 1936; listed as Class J-3 they were numbered 600-604.

Operation

While 4-8-4's are often regarded as "Northerns," a name derived from where the wheel arrangement first saw service on the Northern Pacific in 1926, the C&O chose the moniker "Greenbrier."

This designation referenced a river, as well as a subdivision of the same name, in the Appalachian Mountains of eastern West Virginia. It also referred to a state county and the regal Mountain State resort, which remains open to the public today.

In addition, the railroad named individual engines after prominent Virginia statesmen, perhaps because the locomotives would be leading the company's most highly regarded trains such as the George Washington and Sportsman (the naming of units included only the J-3's and first batch of J-3a's).

The Greenbriers were some of the heaviest and largest 4-8-4's ever built; the original J-3's weighed 477,00 pounds (engine only) while the first batch of J-3a's (#605-606) weighed 506,300 pounds. The second batch of J-3a's (#610-614) weighed in at 482,200 pounds.

Roster

| Class | Number | Name |

|---|---|---|

| J-3 | 600 | "Thomas Jefferson" |

| J-3 | 601 | "Patrick Henry" |

| J-3 | 602 | "Benjamin Harrison" |

| J-3 | 603 | "James Madison" |

| J-3 | 604 | "Edmund Randolph" |

| J-3a | 605 | "Thomas Nelson, Jr." |

| J-3a | 606 | "James Monroe" |

| J-3a | 610-614 | No Name |

These weights provided the locomotive's with substantial tractive efforts, above 66,000 pounds, while 74-inch drivers offered high speeds (reaching nearly 80 mph). The ruling grades on the Allegheny and Mountain Subdivisions reached 1.52%. Nevertheless, the J-3's could pull thirteen heavyweight cars through this territory without difficulty.

According to Thomas Dixon, Jr.'s book, "Chesapeake & Ohio Railway: A Concise History And Fact Book," the Greenbriers of 1935 were the first locomotives built by Lima following the Great Depression.

As late-era designs the J-3's were equipped with several new technologies including trailing truck boosters (increased tractive effort), large tenders capable of handling 22,000 gallons of water and 25 tons of coal, and Timken roller bearings on front and rear trucks (J-3a's).

The C&O's first batch of J-3a's arrived in 1942 and were similar to their earlier counterparts save for the heavier weight as previously mentioned. Perhaps most surprising is the C&O went back for more after World War II, purchasing a second-batch of J-3a's in 1948.

Huddleston

It has been argued by some historians the C&O spent far too much time and money on late-era steam technology when it was inevitable diesels were the future in motive power. As C&O historian Eugene Huddleston notes:

"[It is] simply amazing the expenditure of so much money to produce a 'state of the art' locomotive in the waning days of steam. It seems nothing was sacrificed to equip the new Greenbriers with the latest features and best appliances. Enthusiasm was still the word in 1947, as this writer well recalls from being told about the order for five more Greenbriers from Lima Locomotive Works by locomotive engineer Vince Hiltz."

Nevertheless, Chessie remained a strong proponent of steam well after World War II, even attempting to launch a new streamliner powered by steam turbine technology in the late 1940s, The Chessie. Ultimately, delays in the equipment's arrival and issues with the locomotive shelved the project.

Preservation

Perhaps it is true the company overspent on late-era steam designs although the C&O was wholly-dedicated to the motive power until the end. As a major coal shipper, just like the Norfolk & Western, Chessie believed fervently that steam was on par, if not better, than diesel technology for main line service.

The two railroads may have proven this true if given the time but the secondary steam market for parts and supplies rapidly disappeared as diesels took root making it increasingly expensive to continue operating the motive power. By the early 1950s new models from Electro-Motive began replacing steam on passenger assignments.

Incredibly, as Mr. Dixon notes in his book, the J-3a's of 1948 saw just three years of service here before they were bumped into secondary roles. By 1956, all of the Greenbriers had been retired and only one was saved, #614. It is currently owned by Ross Rowland but is currently not operational.

Class K "Kanawhas" (2-8-4)

Class T-1 (2-10-4)

The C&O's T-1's included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas" types, which entered service just after the country entered the Great Depression. The success of these locomotives in heavy freight service sold the C&O on "Super Power" steam technology.

What was essentially an enlarged Berkshire, the 2-10-4's could handle well over 100-car trains in the rugged western territory with an ability to cruise at-speed.

Following the arrival of these engines virtually all future steam locomotives the railroad purchased were of the "Super Power" variety including such wheel arrangements as the 4-6-4, 4-8-4 Greenbriers, and of course the 2-8-4 Kanawhas. Sadly, no examples of these historic locomotives are preserved.

In this Chesapeake & Ohio publicity photo 2-10-4 #3023 (T-1) has just left the Chicago main line as it hustles westbound/northbound across the Sciotoville Bridge spanning the mighty Ohio River with loads of coal destined for Columbus and Toledo in 1943.

In this Chesapeake & Ohio publicity photo 2-10-4 #3023 (T-1) has just left the Chicago main line as it hustles westbound/northbound across the Sciotoville Bridge spanning the mighty Ohio River with loads of coal destined for Columbus and Toledo in 1943.The C&O used a wide variety of wheel arrangements, from the massive 2-6-6-6 "Allegheny" to the small 2-8-0. These locomotives could be found in service until the end of steam.

In fact, as Tom Dixon notes in "Chesapeake and Ohio Railway: A Concise History and Fact Book," Chessie is said to have had more wheel arrangements in service (18) at the same time than any other railroad except the Santa Fe.

The C&O also employed big steam for fast freight operations, such as the 2-8-4 and the 2-10-4. These locomotive could high-step their way at over 30 mph lugging either heavy coal drags or merchandise trains.

The Texas Types introduced the Chesapeake & Ohio to the age of "Super Power" steam and was the first which its Advisory Mechanical Committee (AMC) took credit in designing. The AMC was an oversight body formed shortly after the Van Sweringen brothers gained control of the C&O in 1923.

Its purpose was to improve and standardize, among other initiatives, motive power across the Van Sweringen-owned properties, which at that time included the C&O, Erie, Nickel Plate, Pere Marquette and Hocking Valley Railway.

As Mr. Dixon points out the AMC, in addition to its research and development department, also held authority over mechanical decisions for each railroad.

The 2-10-4 was spawned from AMC's original interest in Super Power technology. This term chronicles late era steam locomotives which featured large, expanded fireboxes (requiring two trailing axles) that could produce near infinite quantities of steam.

Development

The C&O's 2-10-4's were born from the 2-8-4 Berkshire (or "Kanawhas" on the Chessie), the original Super Power design. This wheel arrangement had first been tested on New York Central's Boston & Albany subsidiary in northwestern Massachusetts during the spring of 1925.

Specifications

It appears the Van Sweringens' quickly recognized the inherent advantages of the 2-8-4 and were immediately impressed with Lima's "Super Power" concept. As Mr. Dixon notes only a few years later, in 1929, the brothers had formed the Advisory Mechanical Committee.

Over the next two decades the AMC refined a range of powerful new locomotives, perhaps the best remembered of which were the so-called 2-8-4 "Van Sweringen Berkshires" found on all of their railroads. The C&O's 2-10-4's rolled out within a year of the committee's formation, working with Lima in doing so.

In creating the T-1's, AMC and Lima based the design from Erie's successful Class S 2-8-4's, essentially stretching the locomotive by including an additional driving axle.

Per the AMC's recommendations the C&O ordered 40 2-10-4's from Lima in 1930, numbered 3000-3039. Not only were these locomotives powerful - able to exert tractive efforts of nearly 94,000 pounds - but with 69-inch drivers could lead a train of empty coal hoppers at 50 mph.

Both the railroad and its employees were very impressed with the 2-10-4's. As C&O historian Eugene L. Huddleston notes, "This was truly one of the greatest locomotives ever built." Mr. Dixon points out that the T-1's were the largest and most powerful non-articulated locomotives ever manufactured when they first entered service in 1930.

The C&O normally assigned them west of the Ohio River where they generally operated between Russell, Kentucky and Toledo, Ohio via Columbus. The engines could regularly handle 14,000-ton, 160-car coal drags to the Lake Erie docks and other points across Ohio.

Sometimes they would also venture east but this was relatively rare. The T-1's operated without major changes or upgrades throughout most of their careers although they did see an increase in boiler pressure to 265 psi, which slightly increased tractive effort.

Retirement

The locomotives were not particularly old by steam standards when their retirement came in 1952-1953. As a major shipper of coal the C&O was a staunch proponent of steam power, so much so that it continued acquiring new locomotives through the late 1940s.

It also took the bold step of testing experimental steam-turbine technology, which ultimately proved unsuccessful. As the secondary steam market faded away the C&O realized diesels were the future and began retiring steam by the mid-1950s. While the company preserved many examples of various wheel arrangements none of the 2-10-4's were saved.

CSX Transportation

The creation of CSX entered the C&O into its last of many long and storied chapters; eventually a new subsidiary known as CSX Transportation was formed to operate the company's railroad assets.

According to Trains Magazine, the Western Maryland was the first to disappear, merged into the B&O on May 1, 1983. The B&O survived until April 30, 1987 when it disappeared into the C&O. Finally, the C&O was formally dissolved as a corporate entity on August 31, 1987.

Today, large segments of the old C&O remain in use, including its main line from Newport News to Cincinnati as well as segments into northern Ohio via Columbus and Toledo.

Unfortunately, most of its route to Chicago has been abandoned in favor of the B&O's line and the segment to Lexington is no longer part of its network. In addition, most of ex-Pere Marquette trackage has either been sold or abandoned.

The

Chesapeake & Ohio Railway will always be remembered for the excellent

railroad it operated throughout much of the 20th century and Chessie the

kitten remains beloved by millions, decades since the railroad has

disappeared.

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 4-6-6-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 10, 25 12:47 PM

The Rio Grande owned some large wheel arrangements, including the 4-6-6-4s. Interestingly, the railroad was never satisfied with these engines. -

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In Michigan

Apr 10, 25 12:06 PM

Michigan offers a variety of passenger train services, allowing travelers to discover the state's beauty and charm in a relaxed and comfortable manner. Learn more here. -

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In Massachusetts

Apr 10, 25 11:55 AM

Massachusetts' passenger and commuter train services offer a reliable and efficient way to navigate the state's diverse landscapes and bustling cities. Learn more here.