Illinois Terminal Railroad: Map, Roster, Photos, History

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Illinois Terminal was a fascinating operation. Its earliest heritage was a small switching line of the same name which carried no interurban ties until its acquisition by the Illinois Traction.

The vision of William B. McKinley, the IT grew into the greatest and most successful interurban ever built linking St. Louis with central Illinois. It was comprised of many subsidiaries although all were under the parent's control.

The hope of opening a direct St. Louis to Chicago corridor ultimately failed and in most respects the IT resembled any other interurban with overhead catenary, rural operations, and considerable street running.

However, from an early period it, largely by accident, enjoyed a bountiful freight business. McKinley recognized this and tailored his operation accordingly.

As passenger traffic declined, freight tonnage grew in importance, eventually totaling several million dollars annually. What began as a hodgepodge of electrified lines had turned into a profitable freight carrier by the postwar years.

Over time the IT abandoned large segments of its property in favor of trackage rights via other railroads (explained in greater detail below). In 1982 it was acquired by Norfolk & Western and today little remains of the original network.

A pair of the Illinois Terminal's recently delivered SD39's, the biggest power the former interurban ever owned, sparkle in the sun at Springfield, Illinois on June 8, 1969. Dick Wallin photo/Warren Calloway collection.

A pair of the Illinois Terminal's recently delivered SD39's, the biggest power the former interurban ever owned, sparkle in the sun at Springfield, Illinois on June 8, 1969. Dick Wallin photo/Warren Calloway collection.History

The Road Of Personalized Services proved a good slogan for the Illinois Terminal, which worked hard over the years to develop its carload freight business while providing high quality service for customers.

As Dr. George Hilton and John Due note in their excellent title, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," the IT blossomed into the largest, end-to-end, traction system in the country with a network of 462 route miles by 1950.

The McKinley Syndicate became involved with a handful of interurbans throughout the country (as well as public utilities) over the years although none reached IT's level of success.

McKinley was an investment broker from Champaign, Illinois and got his start in the growing interurban industry by acquiring the local Danville Street Railway & Light Company (DSR&L) on July 18, 1900.

The immediate history of the Illinois Terminal begins at this time. Shortly after purchasing the DSR&L, McKinley bought the defunct Danville, Paxton & Northern Railroad (DP&N). It was originally incorporated on December 2, 1899 to link Danville with Paxton, Illinois, a distance of more than 40 miles.

McKinley Syndicate

The original promoters envisioned it as just another steam road but later pivoted to the idea of an electrified interurban. Whatever the case, no work took place prior to McKinley's purchase. The first 6 miles opened to Westville on October 20, 1901, south of Danville.

Less than a year later, on May 29, 1902, a short branch was completed to nearby Catlin. A flurry of activity occurred following these events as McKinley began expanding prodigiously. The first involved reaching Georgetown, located slightly more than 4 miles south of Westville.

It was not built by his DP&N but rather local interests who wished to see service extended to their town, opening on August 27, 1902.

At A Glance

St. Louis - Peoria Springfield - Danville Decatur - Bloomington - Mackinaw Junction Alton - Edwardsville - East St. Louis Alton - Granite City - East St. Louis Venice - Mitchell - Grafton Troy Junction - O'Fallon |

|

Diesels: 18 Steam: 14 Electric: 38 Battery Diesel-Electric: 2 Battery Trolley: 1 Diesel Trolley: 1 | |

Freight Cars: 1,868 Passenger Cars: 63 | |

The next move occurred within his hometown of Champaign where the Danville, Urbana & Champaign Railway (DU&C) was incorporated on July 31, 1902 (it went on to acquire the DP&N's assets on April 24, 1903).

The DU&C was intended to head east by connecting St. Joseph with Urbana (about 12 miles, direct service into Champaign came via the small Urbana & Champaign Railway).

With funding in place and right-of-way acquired, work proceeded rapidly. This section was ready by November 9, 1902 as work continued into the following year for through Danville - Champaign operation.

Illinois Terminal car #277 is seen here at the terminal in Peoria, Illinois in 1947. The car was manufactured by the St. Louis Car Company in 1913 and today is preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal car #277 is seen here at the terminal in Peoria, Illinois in 1947. The car was manufactured by the St. Louis Car Company in 1913 and today is preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.Expansion

It took a bit longer than expected due a substation under construction in Fithian (west of Danville) but finally opened on September 6, 1903.

The entire system utilized the standard 600-volt, direct-current system inherent of most interurbans, particularly in the Midwest (IT's northwestern lines, interestingly, carried alternating current technology, explained in more detail later on).

There were two final extensions on this eastern segment; the first included a short branch to Homer (via Ogden) opened on May 25, 1905 while later that year, on October 1st, service was extended from Georgetown to Ridge Farm. As all of this was ongoing, McKinley drew up plans to reach the country's second-busiest gateway, St. Louis.

It began with the incorporation of the Decatur, Springfield & St. Louis Railway (DS&StL) on May 28, 1903. Although disconnected from his eastern lines the DS&StL carried ambitious hopes of connecting all three of its namesake points. To get started, two initial moves were carried out.

For access into Decatur the small Decatur Street Railway & Light Company was acquired while purchase of a defunct right-of-way between Decatur and Springfield provided a ready-made corridor along the northern periphery.

As Hilton and Due's book poignantly notes, the final Illinois Terminal network was comprised of many subsidiaries. This was particularly true of the southwestern lines, mentioned only briefly here.

The Springfield - Decatur segment was built as the Illinois Central Traction Company (ICT). It opened on September 25, 1904 with direct entry into Springfield achieved via the Springfield Consolidated Railway.

In his book, "Illinois Terminal: The Electric Years," author Paul Stringham details the difficulties ITC encountered when attempting to install a crossing over the Illinois Central in Springfield at Capitol Avenue.

Illinois Terminal express car #1202 is seen here at the station in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1950. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal express car #1202 is seen here at the station in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1950. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.This issue became a recurring theme as McKinley experienced similar problems with other large railroads. Most viewed interurbans as a threat to their passenger traffic and, to a lesser extent, freight business. They were openly hostile and usually refused to work with the small electric lines in any way.

This was nearly universal east of the Mississippi River while Midwestern and western carriers were somewhat more receptive (the Chicago Great Western, in particular, openly welcomed interchange). It was an odd reaction considering most interurbans were less than 50 miles in length and carried no, true threat to the big carriers.

System Map (1940)

Reaching St. Louis

Looking south of Springfield, McKinley renamed the DS&StL as the St. Louis & Springfield (StL&S) on December 28, 1903 to build as far as Staunton. From that point, another system was incorporated known as the St. Louis & North Eastern (StL&NE).

It was formed on December 22, 1904 and would finish the line into Granite City along the east bank of the Mississippi River (directly across from downtown St. Louis).

Why McKinley changed tactics and elected to break up construction into several subsidiaries is unclear but by June of 1903 work on the StL&S had begun and the road launched full service on February 16, 1906.

While this project was underway, so too was the StL&NE building northward from Granite City, via Edwardsville. The completed line to Staunton was finished on October 31, 1905 but regular service was delayed until February 16, 1906 as a few construction issues were ironed out.

At the time, McKinley did not have a direct connection into St. Louis, relying instead upon an interchange with the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis's (TRRA).

Even this connection proved tumultuous and he also faced hostilities at East St. Louis (issues here were finally resolved, somewhat tentatively, in late 1906).

Illinois Terminal Class D freight motor #73 at the shops in East Peoria, Illinois, circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal Class D freight motor #73 at the shops in East Peoria, Illinois, circa 1955. American-Rails.com collection.Such problems surely convinced McKinley the only way to offer truly reliable, scheduled service was by maintaining his own line into the city. In the meantime he looked northward and streamlined operations through formation of the Illinois Traction Company in 1904.

As Mike Schafer points out in his book, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III," Chicago was always the goal. This disconnected segment began as the Chicago, Ottawa & Peoria Railway (CO&P) incorporated on April 19, 1907 to acquire the Illinois Valley Railway's assets.

The CO&P slowly expanded east and west of Ottawa in the coming years reaching Joliet, Streator, and Princeton.

Unfortunately, five issues doomed the dream; overextended finances (in particular were costs associated with the massive Mississippi River bridge into downtown St. Louis), the Great Depression, declining ridership by the 1920's, lack of online carload freight, and no through connection.

Despite this setback, McKinley did achieve further expansion above Springfield and Decatur. Once again, a series of subsidiaries accomplished the task.

Illinois Terminal 2-6-0 #23 is seen here near the end of her career in Federal, Illinois, circa 1950. The IT used quite a few of this wheel arrangement but was quick to retire them with the diesel's arrival. This particular unit (produced by Baldwin in 1926) was scrapped soon after this photo was taken. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal 2-6-0 #23 is seen here near the end of her career in Federal, Illinois, circa 1950. The IT used quite a few of this wheel arrangement but was quick to retire them with the diesel's arrival. This particular unit (produced by Baldwin in 1926) was scrapped soon after this photo was taken. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.These corporate subsidiaries included the following:

- Springfield & North Eastern Traction (formed on April 28, 1906 from the Springfield & North Eastern Railroad's reorganization) completed the Springfield - Lincoln segment, launching regular service on December 15, 1906.

- Chicago, Bloomington & Decatur was created on August 19, 1905 to finish the Decatur-Bloomington line, which took about a year and fully opened on August 1, 1906.

- Peoria, Bloomington & Champaign Traction established on April 1905 was assigned the Bloomington - Peoria leg running via Mackinaw, opening on April 21, 1907.

- Peoria, Lincoln & Springfield Traction (PL&ST) which built the Lincoln - Mackinaw connector to provide through service from Peoria to East St. Louis via Springfield.

The PL&ST was incorporated on April 18, 1907, opening on New Year's Day, 1908. Interestingly, while nearly all McKinley's properties utilized the standard 600-volt, direct-current (DC) system the lines between Springfield - Peoria and Peoria - Bloomington were equipped with a 33,000-volt alternating current (AC) operation, stepped down to 3,300 volts at substations.

It was further brought down to just 250 volts by the cars themselves (carrying on-board transformers) for regular operation. The company found the AC system not to their liking and after just two years switched to standard DC power on July 8, 1909.

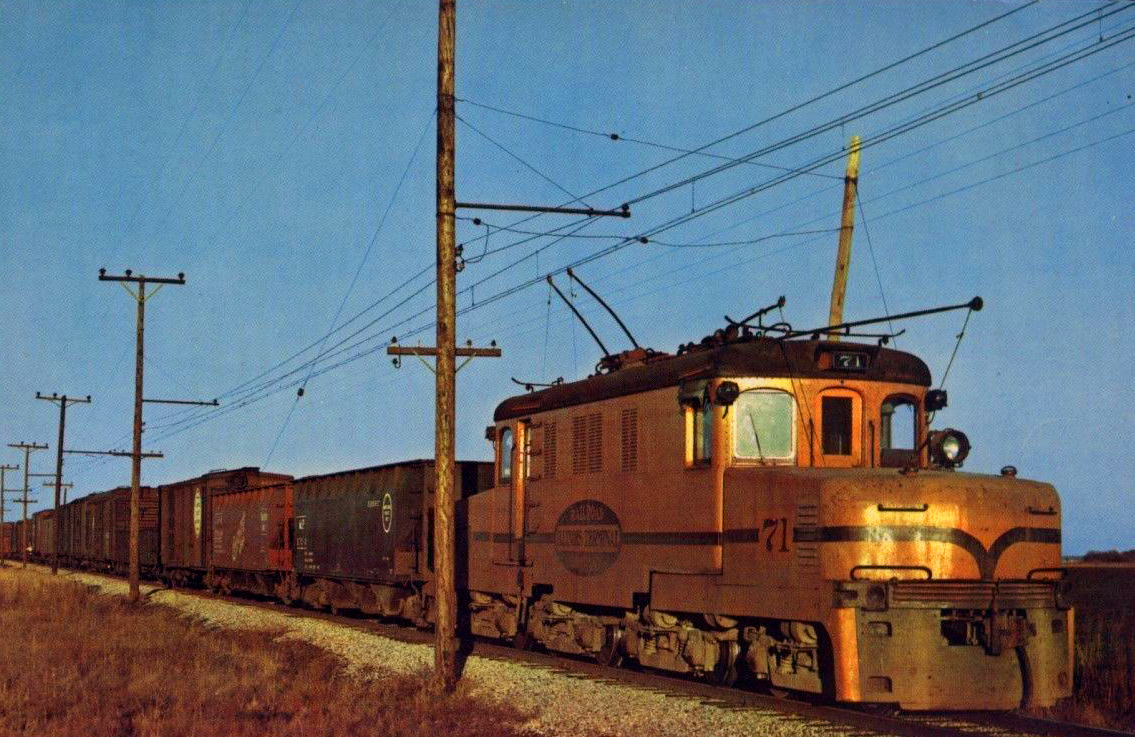

Illinois Terminal "Class D" motor #71 is ahead of Peoria-St. Louis freight #203 during the 1950's. Herbert Georg photo.

Illinois Terminal "Class D" motor #71 is ahead of Peoria-St. Louis freight #203 during the 1950's. Herbert Georg photo.Two final important projects remained; linking the Champaign - Danville section and direct service into St. Louis. The former got underway in 1906 when, on May 26th, yet another subsidiary was formed known as the St. Louis, Decatur & Champaign Railway.

It would run east from Decatur to reach Champaign, linking Bement and Monticello along the way. Construction commenced that same spring and regular service launched on June 16, 1907.

The final endeavor proved the most costly, crossing the river into downtown St. Louis. To do so, McKinley formed a subsidiary known as the St. Louis Electric Terminal Railway on March 8, 1906.

By May of 1907 its line reached the east bank of the river at Venice. In addition, private land had been acquired on the west bank near Salisbury Street leaving only the bridge's construction to achieve downtown access. The incredible project began that August and required three years.

The double-tracked McKinley Bridge (flanked by single highway lanes) was quite a feat of engineering at 8,000 feet in length with a 2,700-foot western approach.

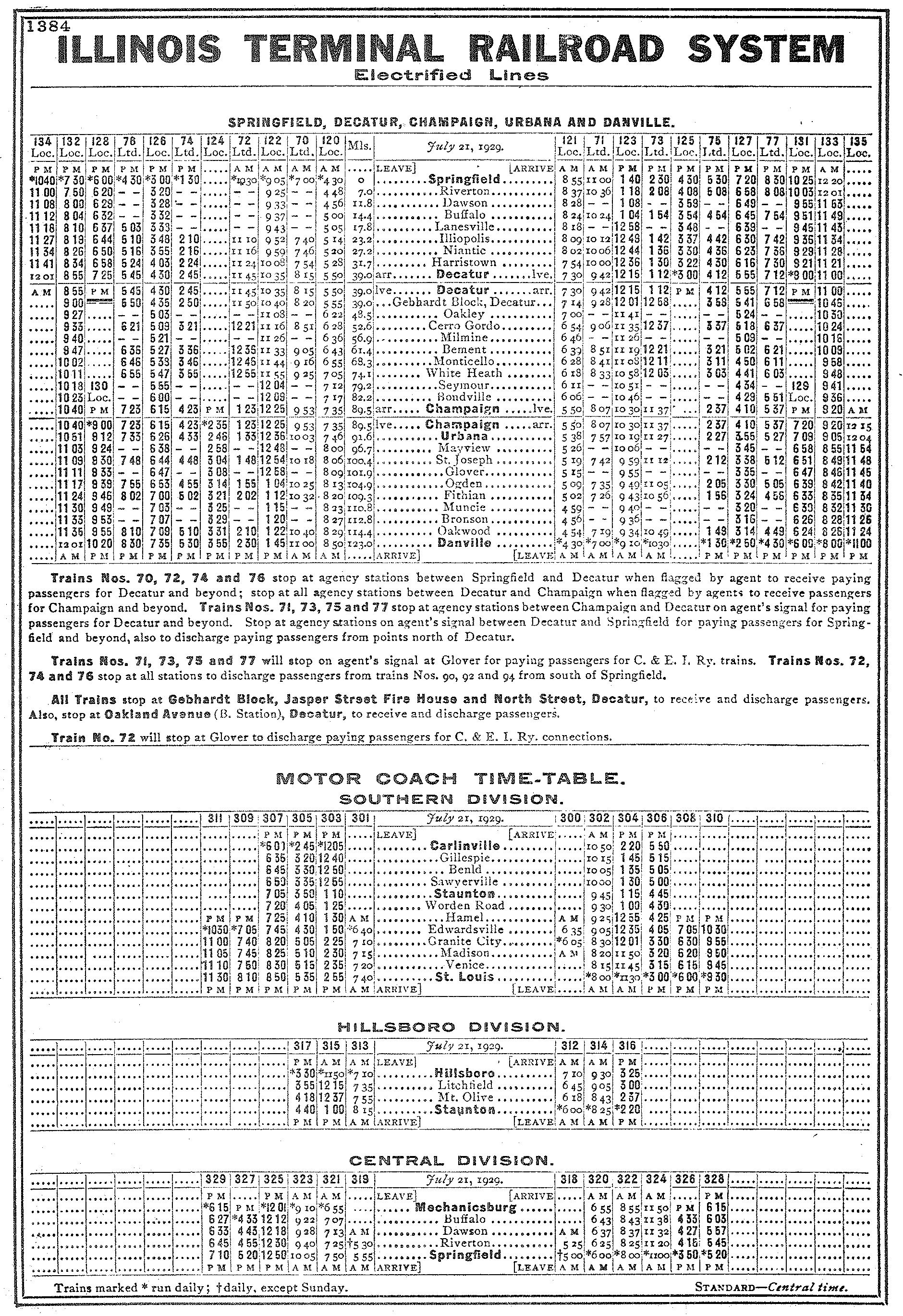

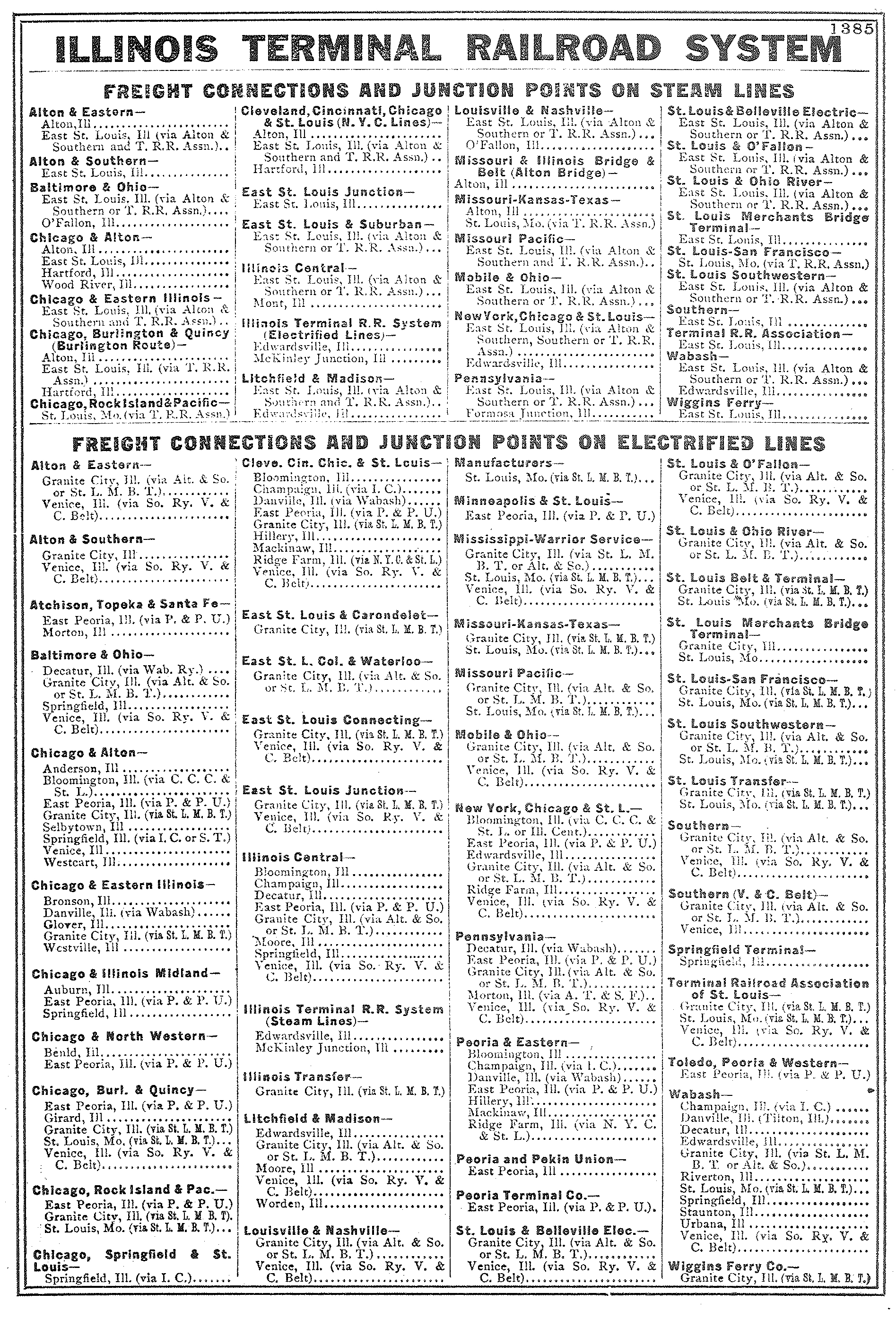

Timetables (1929)

The final price tag was $4.5 million and, ironically, was the greatest span in the city. Regular service launched on October 1, 1910 with trains terminating at Lucas Avenue (in 1933 street running was eliminated when a new facility opened).

While completion of this structure largely signaled the consummation of IT's modern network, a bit more expansion did occur during the 1920's through 1930. As Hilton and Due's book points out it was all situated near St. Louis along the river's heavily industrialized eastern bank.

These acquisitions included the St. Louis & Alton in 1930 for access to the latter town; St. Louis, Troy & Eastern in 1925 to reach Troy; and the Alton & Eastern in 1926 offered additional business between East St. Louis and Grafton. Along with these efforts, new construction provided access as far south as O'Fallon.

Modern Network

Finally, there was the small, steam-powered Illinois Terminal Railroad. This rather insignificant switching line wound up as the face of the entire network. It was formed on July 8, 1895 by Illinois Glass Company to serve its transportation needs in the Alton area.

Within a few years further expansion afforded access to LeClaire/Edwardsville (opened January 11, 1900). The IT was spun off as independent in 1907 and largely remained so for the next two decades, aside from a slight name change in 1922 as the Illinois Terminal Company.

An Illinois Terminal "Streamliner" set at the new terminal in East Peoria, Illinois, circa 1950. There were three such sets manufactured by the St. Louis Car Company in the late 1940s, intended to resurrect the IT's declining passenger business. They were retired following the end of most intercity passenger services in 1956. None survive. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.

An Illinois Terminal "Streamliner" set at the new terminal in East Peoria, Illinois, circa 1950. There were three such sets manufactured by the St. Louis Car Company in the late 1940s, intended to resurrect the IT's declining passenger business. They were retired following the end of most intercity passenger services in 1956. None survive. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.Around this time a series of corporate changes took place; the Illinois Traction, Inc., a subsidiary of the Illinois Power & Light Company (IP&L), was formed in 1923 to maintain all rail services. Then, in 1928 the Illinois Terminal Company was acquired by IP&L with IT subsequently leasing all rail holdings.

In a further corporate simplification the Illinois Terminal Railroad was created on October 18, 1937 in a consolidation of the Illinois Terminal Company and all of its leased assets. From that point forward, the interurban operated as a unified system under one name.

Illinois Terminal car #284 is seen here on the wye in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1950. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal car #284 is seen here on the wye in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1950. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.By then, McKinley had left the company to pursue politics whereupon the IT passed through various owners including Clement Studebaker, Jr. (of the Studebaker Corporation, an automobile manufacturer), Samuel Insull, and finally the North American Company when Insull's empire collapsed during the Great Depression.

The IT returned to independence during the 1930's and spent the following two decades as such until its 1956 purchase by a consortium of large Class I's including the Baltimore & Ohio; Chicago & Eastern Illinois; Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific; Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; St. Louis-San Francisco; Gulf, Mobile & Ohio; Illinois Central; Litchfield & Madison; New York Central; Nickel Plate; and Wabash.

Passenger Trains

Capitol Limited: (St. Louis - Peoria)

City of Decatur: (St. Louis - Decatur)

Fort Crevecoeur: (St. Louis - Peoria)

Illini: (St. Louis - Champaign)

Illmo Limited: (St. Louis - Peoria)

Mound City: (St. Louis - Peoria)

Owl: (St. Louis - Peoria)

Peoria Flyer: (St. Louis - Peoria)

St. Louis Flyer: (Peoria - St. Louis)

Sangamon: (St. Louis - Peoria)

Illinois Terminal cars #1202 and #284 (both products of the St. Louis Car Company) stopped at the station in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1954. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Illinois Terminal cars #1202 and #284 (both products of the St. Louis Car Company) stopped at the station in Decatur, Illinois, circa 1954. James Stitzel photo. American-Rails.com collection.Aside from its heavy carload freight business and numerous interchange connections the modern Illinois Terminal varied only slightly from what you might expect of a typical interurban. As traffic increased the company was forced to employ ever larger boxcab motors.

It began with the small Class A "steeple cab" switchers, 800 horsepower machines which transitioned in the later years to beefier Class B's (1,000 horsepower). This motor was followed by Class C's and, finally, the hefty 1,800 horsepower Class D's.

While McKinley had designed his system as a passenger carrier its freight business became so dense focus shifted to meet this growing demand. The IT handled virtually everything imaginable from coal and merchandise to grain and perishables.

As tonnage grew, street operations became unbearable. To alleviate this issue a series of belt lines were constructed fairly early on to bypass Springfield, Decatur, and Edwardsville. The IT then convinced the Wabash and Illinois Central to electrify part of their trackage around Champaign and Urbana in 1927 to also circumvent these towns.

As the years passed, freight accounted for much of the carrier's gross revenues; $1.6 million in 1924, $2.2 million in 1926, and a whopping $11 million by 1954 (with $600,000 in passenger earnings that year).

Norfolk Southern's nod to the Illinois Terminal, SD70ACe #1072 at the heritage celebration in Spencer, North Carolina during early July of 2012. Dan Robie photo.

Norfolk Southern's nod to the Illinois Terminal, SD70ACe #1072 at the heritage celebration in Spencer, North Carolina during early July of 2012. Dan Robie photo.For most interurbans, reaching the six figure mark was an accomplishment making the IT's numbers quite impressive. As Due and Hilton note, by the postwar period its gross revenues were comparable to the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway's (Monon), Indiana's regional Class I.

After the large railroads took control many changes resulted including phasing out the electrification and abandoning corridors in favor of trackage rights (Danville - Ogden was let go in 1952 [cutback to Champaign a year later] and the Forsythe - Mackinaw and Alton - Grafton sections were removed in 1953).

While the Illinois Terminal and its predecessors are widely recognized as an electrified interurban, it also operated a small fleet of steam locomotives, including three 2-8-2's, listed as Class 30. Seen here is #32 at Federal, Illinois in January, 1950, just a month before the unit was sold for scrap. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

While the Illinois Terminal and its predecessors are widely recognized as an electrified interurban, it also operated a small fleet of steam locomotives, including three 2-8-2's, listed as Class 30. Seen here is #32 at Federal, Illinois in January, 1950, just a month before the unit was sold for scrap. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Steam ended on June 30, 1950 when 2-6-0 #21 dropped its fire. The final through passenger runs were carried out in 1956 while suburban service (St. Louis - Granite City) survived until June 21, 1958. At that point, the IT became a freight-only, entirely dieselized operation.

Interestingly, despite increasing freight tonnage its infrastructure never saw considerable improvements. It continued relying primarily on the 70-pound rail with which it was originally constructed.

As Mr. Stringham's book points out, the big Class D motors were too heavy for this track, weighing approximately the same as Electro-Motive's early GP7 road-switcher.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | 1967-1968 Re-Numbering | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | 700-711 | 1001-1012 | 1948-1950 | 12 |

| RS1 | 751-756 | 1051-1056 | 1948-1950 | 6 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | 1967-1968 Re-Numbering | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW8 | 725 | 801 | 1950 | 1 |

| SW1200 | 775-786 | 1201-1212 | 1955 | 12 |

| F7B | - | 1507-1508 (Ex-RF&P) | 1949-1959 | 2 |

| SW1500 | - | 1509-1515 | 1970 | 7 |

| GP7 | 1600-1605 | 1501-1506 | 1953 | 6 |

| GP7u | - | 1750 (Ex-Wabash) | 1952 | 1 |

| GP38-2 | - | 2001-2004 | 1977 | 4 |

| GP20 | - | 2008-2009 (Ex-UP) | 1960 | 4 |

| SD39 | - | 2301-2306 | 1969 | 6 |

Electric Roster

| Number(s) | Class | Builder | Type | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51-52 | - | St. Louis | B-B | 1930 |

| 53 | - | Decatur Shops | B-B | 1942 |

| 61 | - | Decatur Shops | B-B | 1939 |

| 61 | - | Decatur Shops | B-B | 1939 |

| 70-74* | D | Decatur Shops | B-B+B-B | 1940-1942 |

| 1550 (1st) | A | Danville Car | B-B | 1907 |

| 1550 (2nd) | A | Danville Railway & Light | B-B | 1904 |

| 1551-1555 | A | Danville Car | B-B | 1904-1907 |

| 1556 (1st) | A | Danville Railway & Light | B-B | 1904 |

| 1556 (2nd) | A | Danville Car | B-B | 1907 |

| 1557 (1st) | A | Danville Railway & Light | B-B | 1904 |

| 1557 (2nd) | A | Danville Car | B-B | 1907 |

| 1558 | A | Danville Railway & Light | B-B | 1904 |

| 1559-1560 | A | Alco/GE | B-B | 1907 |

| 1561 (1st)** | B | Alco/GE | B-B | 1907 |

| 1561 (2nd)** | B | Decatur Shops | B-B | 1910 |

| 1562-1578** | B | Decatur Shops | B-B | 1910 |

| 1579-1581*** | C | Decatur Shops | B-B+B-B | 1924 |

| 1582-1584*** | C | Decatur Shops | B-B+B-B | 1925 |

| 1585-1586*** | C | Decatur Shops | B-B+B-B | 1926 |

| 1587-1598*** | C | Decatur Shops | B-B+B-B | Unknown |

* The Class D motors weighed an astonishing 217,000 pounds and with eight Westinghouse motors producing 225 horsepower offered an hourly rating of 1,800 horsepower.

Their lineage is as follows: #70 rebuilt from #1580 (9/10/40); #71 rebuilt from #1581 (3/27/41); #72 rebuilt from #1591 (12/12/42); #73 rebuilt from #1584 (1/2/42); and #74 rebuilt from #1588 (9/26/42).

** The Class B electrics carried four, 200 horsepower motors from General Electric offering 800 horsepower.

*** The Class C motors carried eight General Electric motors offering 125 horsepower, providing them an hourly rating of 1,000 horsepower.

The "Streamliners"

| Number(s) | Type | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300-302 | Baggage/Coach Combine | St. Louis Car Company | 1948-1949 |

| 330-331 | Coach | St. Louis Car Company | 1948-1949 |

| 350, Louis Jolliet | Parlor-Diner-Observation | St. Louis Car Company | 1948-1949 |

| 351, Shadrach Bond | Parlor-Diner-Observation | St. Louis Car Company | 1948-1949 |

| 352, Pierre Laclede | Parlor-Diner-Observation | St. Louis Car Company | 1948-1949 |

All above roster information is thank to William Middleton's "Traction Classics: The Interurbans, Extra Fast And Extra Fare" and "Traction Classics: The Interurbans, Interurban Freight" as well as Paul Stringham's "Illinois Terminal: The Electric Years."

An Illinois Terminal 0-8-0 switcher, #38 (Class A), is seen here near the end of her career in Federal, Illinois, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.

An Illinois Terminal 0-8-0 switcher, #38 (Class A), is seen here near the end of her career in Federal, Illinois, circa 1950. Fred Byerly photo. American-Rails.com collection.Norfolk & Western

To help meet demand in the 1960's IT purchased the largest and most powerful diesels it would ever own, second-generation SD39's and GP38-2's.

By the early 1980's most of its principle owners were no longer interested in the property except for Norfolk & Western, which by then had absorbed the Wabash and Nickel Plate Road. This led to others selling out and N&W officially taking control on May 8, 1982.

At that time trackage still in service included Granite City - Alton, Madison - Edwardsville - Alton, and Maroa (Decatur) - Farmdale Junction (Peoria). The latter segment had originally been abandoned by IT years earlier.

However, when Conrail launched on April 1, 1976 it had no interest in a former Pennsylvania Railroad branch (57 miles) serving the same territory, allowing IT to purchase this trackage.

Today, while many of its former lines have been abandoned some continue to see use under N&W successor Norfolk Southern. Finally, many of IT's former substations still stand, although most are abandoned and in very poor condition.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Minnesota Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 22, 25 12:17 PM

The state of Minnesota has always played an important role with the railroad industry, from major cities to agriculture. Today, several museums can be found throughout the state. -

Massachusetts Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 11:41 PM

There are a handful of museums located in the state of Massachusetts detailing its long and storied history with trains, which can be traced back to the industry's earliest days. -

Maryland Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 01:36 PM

The state of Maryland is where it all began with the Baltimore & Ohio. Along with the B&O Railroad Museum, several other similar organizations can be found in the state.