Great Northern Railway: Map, Logo, Rosters, History

Last revised: October 12, 2024

By: Adam Burns

What became the Great Northern Railway (GN) was the work of a singe individual, James Jerome Hill. The legendary "Empire Builder" pieced together one of America's great transportation companies over the span of nearly four decades.

It all began with the small St. Paul & Pacific and, by the time of his passing in 1917, the GN was a transcontinental carrier of more than 8,000 miles.

History

Hill was a methodical, driven, and excellent railroader who was so good at his profession he sometimes worked as a consultant for others.

The tycoon always planned his next move well in advance and was rarely caught off-guard. As a result, the superb management Hill instilled at Great Northern continued throughout its corporate existence.

Over time, the company's traffic became highly diversified; what began as an agricultural hauler transformed into a transcontinental carrier handling every type of freight imaginable.

In this Great Northern publicity photo, FT's lead new 40-foot boxcars near Minneapolis in 1949. American-Rails.com collection.

In this Great Northern publicity photo, FT's lead new 40-foot boxcars near Minneapolis in 1949. American-Rails.com collection.It even enjoyed an important connection with the Western Pacific in Northern California. The GN experienced only one bout of financial hardship in the years immediately following the Great Depression.

It had soon rebounded from these lean times and more or less boasted strong profits until the "Hill Lines" were merged into Burlington Northern, Inc. (BNI) on March 2, 1970.

At A Glance

8,368 (1930) 8,316 (1952) | |

St. Paul - Willmar, Minnesota - New Rockford, North Dakota - Havre, Montana - Sandpoint, Idaho - Spokane, Washington - Seattle Minneapolis - St. Cloud, Minnesota - Fargo, North Dakota - Grand Forks, North Dakota - Minot Superior, Wisconsin/Duluth, Minnesota - Crookston, Minnesota - Grand Forks, Minnesota Minneapolis/St. Paul - Brook Park, Minnesota - Duluth/Superior Barnesville, Minnesota - Crookston - Winnipeg, Manitoba Portland, Oregon - Seattle - Vancouver, British Columbia Willmar - Sioux Falls, Iowa Havre - Great Falls - Helena - Butte, Montana Shelby - Great Falls - Billings, Montana Bend, Oregon - Klamath Falls, Oregon - Bieber, California (Inside Gateway) | |

Freight Cars: 39,055 Passenger Cars: 579 | |

Interestingly, James J. Hill did not start out in the railroad industry. He was born in the small community of Guelph, Upper Canada (Ontario) on September 16, 1838 to parents who were humble farmers.

He only attended school until the age of 15 after his father's premature death. Two years later he set out on his own and eventually wound up in St. Paul, Minnesota by July of 1856. There, he took a job as a shipping clerk with J.W. Bass & Company.

Despite failing to complete his formal education, Hill blossomed into a sharp and cunning businessman. After learning the freight forwarding trade, he worked as an agent for a number of companies in this arena.

As a result, Hill often dealt with railroads; he not only became quite successful at his profession but also well respected.

Logo

Before long, he had established his own company under the name, J.J. Hill & Company. In the late 1860's he, and a few associates, formed Hill, Griggs & Company.

They then went into the steamboat business and their first steamer, the Selkirk, entered service along the Red River on April 23, 1871. Given his considerable dealings, and keen understanding of their operations, Hill soon sought railroad ownership.

St. Paul & Pacific Railroad

Following much work and drawn out negotiations he, along with three other associates (Donald Alexander Smith, Norman Wolfred Kittson, and George Stephen), signed an agreement to purchase control of the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad on March 13, 1878.

During that era the StP&P was a respectable system albeit mired in financial difficulty; it operated a 214-mile extension from St. Paul to Breckenridge along with a branch to Melrose, which split from Minneapolis.

The latter also included a 100-mile disconnected segment linking Glyndon with Crookston, envisioned as a continuous corridor reaching the Canadian border at St. Vincent. Unfortunately, financial issues and the Panic of 1873 precluded its completion at that time.

Once Hill and company took control they rushed to finish this extension. According to the Minnesota state legislature, a requirement of their ownership stipulated they must do so before the end of 1878! Hill immediately went to work procuring the necessary capital and political means needed.

His efforts were so swift the StP&P dispatched its first train from St. Vincent to St. Paul, running via Breckenridge and Barnesville, on November 10, 1878. It was a sign of things to come.

A Great Northern publicity photo of the postwar "Empire Builder" (Chicago - Seattle) led by new E7A's circa 1947. Author's collection.

A Great Northern publicity photo of the postwar "Empire Builder" (Chicago - Seattle) led by new E7A's circa 1947. Author's collection.St. Paul, Minnesota & Manitoba Railway

A month later, on December 2nd, the complete route to Winnipeg, Manitoba was finished allowing for through traffic to flow out of Canada.

After overseeing these projects, Hill set about forming his own system that would acquire StP&P's assets. This was achieved when the St. Paul, Minnesota & Manitoba Railway (StPM&M) was formed the following spring (May 23, 1879).

Hill's next assignment involved opening a more direct connection into St. Paul, which required competing a 70-mile gap between Alexandria and Barnesville (finished in late 1879).

Afterwards, the Empire Builder began adding hundreds of miles in agricultural branches to serve farms situated at, or near, the Red River.

One particularly important acquisition was the St. Paul & Duluth (StP&D), a railroad jointly owned by the StPM&M; Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (Milwaukee Road); and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha ("The Omaha Road") which offered all three a through a key connection into the Lake Superior ports of Duluth/Superior.

A trio of Great Northern's 1-C+C-1 electrics (Class Y-1) layover at the engine house in Skykomish, Washington during the summer of 1955. American-Rails.com collection.

A trio of Great Northern's 1-C+C-1 electrics (Class Y-1) layover at the engine house in Skykomish, Washington during the summer of 1955. American-Rails.com collection.According to the book "The Great Northern Railway, A History" by authors Ralph W. Hidy, Muriel E. Hidy, Roy V. Scott, and Don L. Hofsommer, in 1880 StPM&M's operating revenue was $2.885 million, a number which had jumped to $8.586 million by 1889.

Similarly, net income rose from $556,000 to $1.069 million during that time. As Hill's empire expanded he worked to improve its terminal facilities in the Twin Cities area.

Arguably its most impressive project was a grand stone-arch bridge spanning the mighty Mississippi River which crossed the magnificent Falls of St. Anthony at an angle.

This structure linked St. Paul with a grand new passenger station in downtown Minneapolis that was situated on Hennepin Avenue along the waterfront.

The 2,300-foot structure was designed by StPM&M's chief engineer, Charles Smith, and constructed of Ohio granite. Its deck was capable of supporting two tracks and after a few years of work carried its first revenue train on April 16, 1884.

According to the industrial publication, Railroad Gazette, the bridge was heralded as "one of the greatest specimens of engineering skill in the country."

System Map (1967)

Expansion

With a Midwest fast becoming a crowded web of railroads, Hill looked westward. As, "The Great Northern Railway, A History" further points out he also had other reasons for doing so which included an economic rebound and instability of Red River wheat shipments.

To escape the congestion he sought an extension into Montana which contained fertile lands of agriculture, timber, and natural ores. To do this he acquired an interest in the Montana Central Railway during 1885, an as-yet built system chartered to link Great Falls with Butte.

Just a year later, in 1886, his StPM&M began building west from its end of track at Devil's Lake, Dakota Territory. Hill was aiming for a connection with the Montana Central at Great Falls, which was underway itself.

Both projects continued throughout 1887 until StPM&M rails had reached Great Falls on October 16th (service commenced on October 31st).

With the grade already prepared, crews continued southwesterly towards Butte but were delayed by the impending winter. This mining town was finally reached the following fall on November 10, 1888.

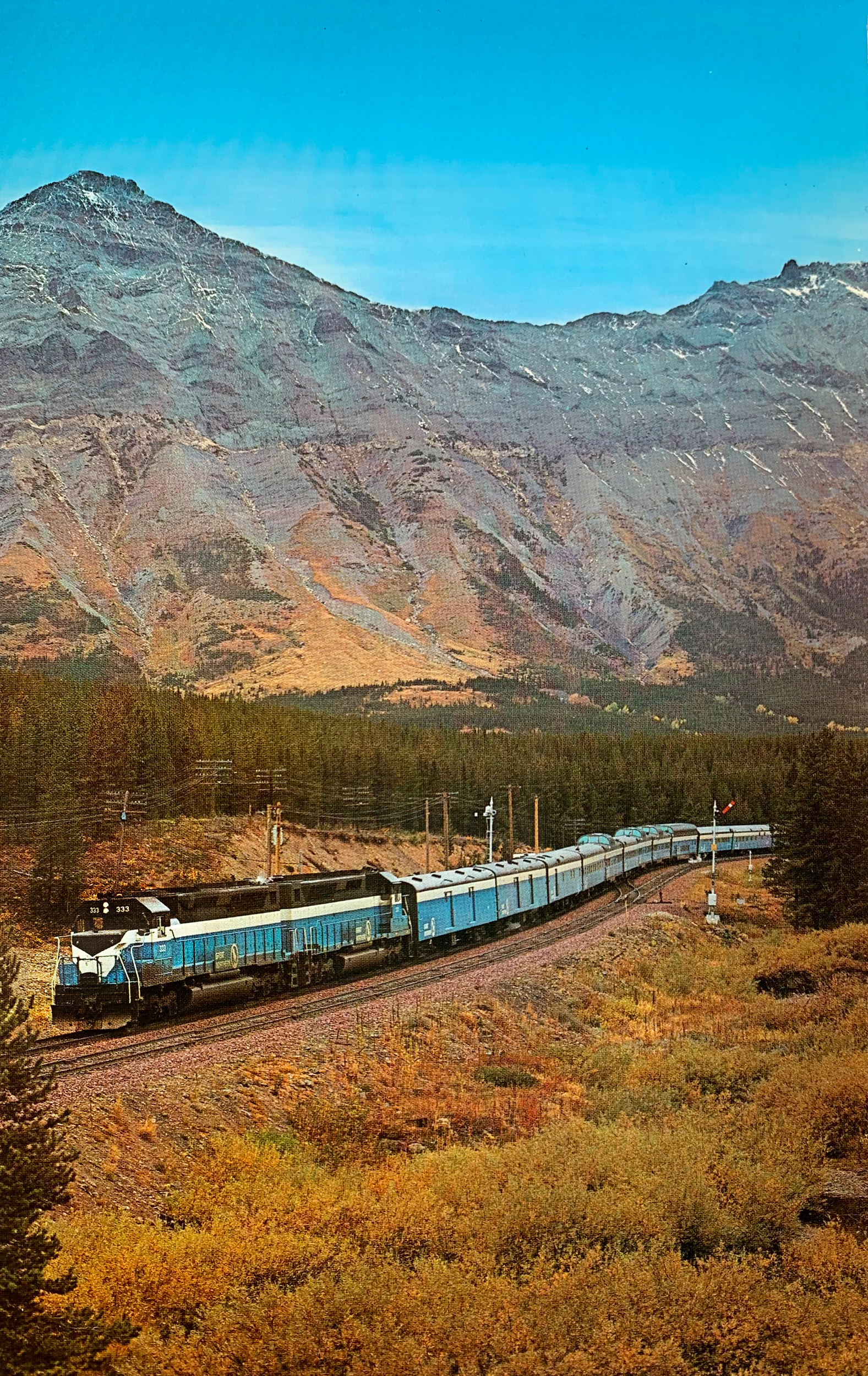

In this Great Northern publicity photo, new SDP45's have the westbound "Empire Builder," adorned in its updated "Big Sky Blue" livery, skirting Glacier National Park near Belton, Montana in the fall of 1967. Author's collection.

In this Great Northern publicity photo, new SDP45's have the westbound "Empire Builder," adorned in its updated "Big Sky Blue" livery, skirting Glacier National Park near Belton, Montana in the fall of 1967. Author's collection.By the late 1880's the StPM&M had grown into a major player across the Upper Midwest with a network of more than 1,000 miles.

As he built west, Hill also remained focused back east. He was never satisfied with the StP&D arrangement and sought his own route into Superior/Duluth.

As he viewed it, having full ownership of any line was always the most advantageous scenario. The StPM&M subsequently sold its stakes in StP&D then formed the Eastern Railway Company of Minnesota in August of 1887.

Just a year later the new, 68-mile line opened for service on September 23, 1888 (regular passenger trains began plying the route on July 17, 1889).

To further boost the company's situation at these port towns, Hill reentered the steamboat business by forming the Northern Steamship Company on June 12, 1888 to handle freight from Buffalo, New York.

His fleet of lake boats included the Northern Light, North Wind, Northern King, Northern Wave, North Star, and Northern Queen.

While Montana did open new business for the StPM&M, the Empire Builder soon realized his company must reach the Puget Sound for a secure financial future. Doing so, however, required a bit of corporate maneuvering.

Transcontinental Extension

On September 16, 1889 Hill's Minneapolis & St. Cloud Railroad was renamed as the Great Northern Railway with intentions of using the former's charter to continue his trek westward.

Following chief engineer Elbridge H. Beckler's surveying efforts, track-laying began at Pacific Junction, Montana (slightly west of Havre) on October 20, 1890.

From this point the line crossed Western Montana's 5,214-foot Marias Pass (within what is now Glacier National Park) before arriving in Spokane and, finally, Seattle.

Along the way it crossed Stevens Pass within Washington's Cascade Mountains, an area which saw two magnificent tunnels constructed over the years.

The entire endeavor was slow but methodical; at the end of 1891 tracks had reached Kalispell and on June 1, 1892 arrived in Spokane, Washington.

After another year the entire Pacific Extension was complete when crews working from opposite directions met at Madison, Washington (today known as Scenic) on January 6, 1893.

The extension ran as far west as Everett where it tied in to another Hill property, the so-called Seattle & Montana Railway (S&M).

This subsidiary operated 78 miles on a north-to-south extension running the coast between Seattle and Blaine on the Canadian border.

It was completed on February 14, 1891; altogether the Great Northern operated 1,727 miles west of St. Paul. For Hill, the S&M was only the beginning out west.

While he is widely recognized for completing the Pacific Extension the Empire Builder also established GN's dominating presence throughout the Puget Sound region.

As Hill put it, the railroad needed its own Portland-Vancouver line to procure the needed business in paying for the route's exorbitant construction costs. The latter city was reached in 1904 and the former in March, 1908.

It all began as the Portland & Seattle Railway, formed in August of 1905, which was renamed the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway in 1908. Only eight months after reaching Portland, the SP&S arrived in Spokane.

The SP&S would later expand further into Oregon by acquiring two electrified interurbans; the Oregon Electric Railway and United Railways. The former ran south of Portland to Eugene while the latter extended east to the coast.

Hill continued his escapades into the Beaver State by picking up the Oregon Trunk Railway in August of 1909. This small system extended from Wishram, along the SP&S, to Bend when it opened on November 1, 1911. There would be further extensions here albeit not until after Hill's passing.

Through it all, Seattle became the established western terminal when GN acquired 60 acres between Smith's Cove and Salmon Bay at a cost of $1 million.

It was here where yards, shops, and docks were located. It seems that every time the great tycoon stated his empire was complete, the railroad just kept growing.

Great Northern 0-8-0 #835 carries out switching chores in the Twin Cities during the fall of 1955. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Great Northern 0-8-0 #835 carries out switching chores in the Twin Cities during the fall of 1955. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.In the east, Hill kept a close eye on Minnesota's rapidly expanding iron ore industry, situated in the Mesabi and Vermillion Ranges.

It was already served by two railroads; the Duluth, Missabe & Northern (DM&N) and Duluth & Iron Range. (D&IR, the two would later merged to form the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range in 1937.)

In his book, "Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range Railway," author John Leopard notes Hill took an unassuming approach in reaching this lucrative arena. He first purchased tracts of land in the western Mesabi Range but then could not locate a railroad.

That chance finally came when the Duluth & Winnipeg Railroad entered receivership following the financial Panic of 1893. The system was about 100 miles in length running from Superior, Wisconsin to Deer River, Minnesota.

It was subsequently reorganized as the Duluth, Superior & Western Railway (DS&W) in 1896 but remained under the Canadian Pacific Railway's control.

Hill, who fervently believed Minnesota's pure iron ore could yield huge profits for his company, eventually worked out an agreement with CP president, William Cornelius Van Horne.

Great Northern B-D+D-B double-end motor #5019 (W-1), is seen here in Skykomish, Washington as part of the Cascade Tunnel electrification on June 9, 1956. Stan Kistler photo. Author's collection.

Great Northern B-D+D-B double-end motor #5019 (W-1), is seen here in Skykomish, Washington as part of the Cascade Tunnel electrification on June 9, 1956. Stan Kistler photo. Author's collection.On April 26, 1897 the Empire Builder purchase control of the DS&W and shortly thereafter added a nearby property, the Duluth, Mississippi River & Northern. This small logging railroad had opened from Mississippi Landing to Hibbing, along the Mesabi Range's western fringe, by 1895.

Using his own money, Hill purchased the system himself for $4.05 million on May 1, 1899. In the succeeding years, ore, a vital component in the steel-making process, continued to play an important role for Great Northern. During the 20th century Hill's greatest achievement was establishing the so-called "Hill Lines."

As previously-mentioned he acquired full control of the Northern Pacific in late 1900 and completed the jointly-owned SP&S later that decade.

With what was now essentially a monopoly into the Pacific Northwest, he angled for a route into Chicago, then America's railroad capital. To do this his NP and GN purchased a 97% stake in the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy by November of 1901.

Another powerful tycoon, Edward Harriman, had wanted the CB&Q for himself to provide his Union Pacific and Southern Pacific with a direct entry into the Windy City.

Modern Era

Denied by Hill, he retaliated by acquiring more combined common and preferred stock in the Northern Pacific than Hill and his ally, J.P. Morgan. The purpose of this move was actually quite calculated as Harriman could use his NP influence to control the CB&Q.

The crafty Empire Builder countered by establishing the Northern Securities Company on November 12, 1901. It acted as a holding company for all three properties (Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Spokane, Portland & Seattle) and retained Hill's leverage.

In essence, this was the first attempt to merge the "Hill Lines" but it was not to be. A Supreme Court order in 1904 forced Northern Securities to divest control of all three although, in the end, Hill was victorious.

Harriman and his colleagues had sold their NP stock back in late 1902. After Northern Securities was disbanded they tried to regain their interests in the railroad.

However, the same court ruled against the group in 1905. In the succeeding years Great Northern and its allies worked hard to establish more efficient operations, cut costs, and raise profits whenever possible. Hill died on May 29, 1917 at the age of 77 but strong management continued to define his railroads long after his passing.

From the Great Northern's 1963 annual report, new GP30's with eastbound time freight #82 (Seattle - Twin Cities) at Wenatchee, Washington in September of 1963.

From the Great Northern's 1963 annual report, new GP30's with eastbound time freight #82 (Seattle - Twin Cities) at Wenatchee, Washington in September of 1963.The Great Northern weathered government control during World War I when the United States Railroad Administration nationalized the railroads at noon on December 28, 1917. The directive was ordered by President Woodrow Wilson in response to fears of gridlock.

Unfortunately, the government did no better at maintaining fluid operations than the private sector; during this time equipment was rundown and infrastructure inadequately maintained to meet the crushing demand.

The GN survived this ordeal relatively unscathed although it did suffer an exorbitantly high operating ratio which had jumped to 83.8% by 1918.

It was returned to private ownership, along with the rest of the industry, on February 28, 1920 following passage of the Transportation Act. That decade witnessed two significant events; GN's last noteworthy expansion and an improved grade over Stevens Pass.

The former was known as the "Inside Gateway," an extension of its line from Bend to Bieber, California that opened in September of 1931. There it met the Western Pacific which built north from its main line at Keddie, California.

A formal Golden Spike ceremony was held in Bieber on November 10, 1931 and the two roads enjoyed a lucrative partnership of handling traffic from Oakland/San Francisco to Chicago in competition against Southern Pacific.

A Great Northern publicity photo featuring the late-era, original "Empire Builder" wearing the short-lived "Big Sky Blue" livery and led by a pair of SDP45's in 1967. Even at this time the train featured far more than you will find on any Amtrak consist today including (not in order) a pair of sleepers, diner, Great Dome observation-lounge, standard coach, three dome coaches, and a lounge-coffee shop (the "Ranch Lounge"). Author's collection.

A Great Northern publicity photo featuring the late-era, original "Empire Builder" wearing the short-lived "Big Sky Blue" livery and led by a pair of SDP45's in 1967. Even at this time the train featured far more than you will find on any Amtrak consist today including (not in order) a pair of sleepers, diner, Great Dome observation-lounge, standard coach, three dome coaches, and a lounge-coffee shop (the "Ranch Lounge"). Author's collection.The other involved an improved Cascade Tunnel. The original was a 2.63-mile bore opened in 1909 to eliminate grades as high as 4%.

As early as 1912 Hill had wanted to further improve GN's line over the pass by constructing a massive tunnel as long as 17.5 miles, which was projected to cost $27 million.

However, delays, such as World War I, shelved the project for more than a decade. Finally, it was dusted off in 1925 and required three years to complete.

A grand ceremony was held on January 12, 1929 to dedicate the structure which was an impressive 7.77 miles in length carrying a grade of 1.6% from east to west.

Passenger Trains

The Great Northern Railway, and other western railroads, are often never recognized for their hard work in creating several of our national parks.

As John Kelly notes in his book, "Great Northern Railway: Route Of The Empire Builder," company president Louis Hill (son of James Hill) and George Grinnell, a magazine publisher, relentlessly pressed the federal government for establishment of a park to protect western Montana's natural beauty.

After much hard work their efforts paid off when a bill establishing Glacier National Park was signed into law by President William Howard Taft on May 11, 1910.

Afterwards, three hotels, built in the style of Swiss Chalets, were constructed to attract vacationers: Prince of Wales Hotel, Glacier Park Hotel, and Many Glacier Hotel.

Like many railroads, GN had an ulterior motive for the park's creation; to increase ridership on its trains by marketing these natural wonders.

The Great Northern enjoyed many years of success dispatching fabulous trains like the Empire Builder, Western Star, and Oriental Limited, that whisked thousands annually to an from the Pacific Northwest.

Badger: (Twin Cities - Superior/Duluth)

Cascadian: (Seattle - Spokane)

Dakotan: (Twin Cities - Williston, North Dakota)

Empire Builder: (Chicago - Seattle)

Gopher: (Twin Cities - Superior/Duluth)

International: (Seattle - Vancouver, B.C.)

Oriental Limited: Served Chicago and Seattle/Portland via allying roads CB&Q and SP&S.

Red River: (Twin Cities - Grand Forks)

Western Star: (Chicago - Seattle)

Winnipeg Limited: (Twin Cities - Winnipeg)

It had cost $25.6 million and remains in use today under successor BNSF Railway. Just months after it opened the country slipped into its worst-ever depression following the stock market crash of 1929. The Great Northern was thrust into is worst-ever traffic slump as the economy collapsed.

It lost money for the only time in its corporate existence when it posted a net deficit of $13.4 million in 1932. A year later this had recovered to a loss of $3.2 million and, in 1934, losses were only $1.074 million.

By 1935 the railroad was back in the black, reporting a strong net income of $7.139 million; from there, numbers steadily climbed. Despite these lean times GN never slipped into receivership like so many other railroads.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1-10 | 1950 | 10 |

| RS1 | 182-185 | 1944 | 4 |

| RS3 | 197-199, 220-224, 228-232 | 1950-1953 | 13 |

| RS2 | 200-219 | 1947-1950 | 20 |

| FA-1 | 276A-276B, 310A-310C, 440A-440D, 442A-442D | 1948-1950 | 6 |

| FA-2 | 277A-278A, 277B-278B | 1950 | 4 |

| FB-2 | 278B-279B | 1950 | 2 |

| FB-1 | 310B, 440B-440C, 442B-442C | 1948-1950 | 5 |

| FPA-2 | 277A-277B (Ex-Demonstrators) | 1950 | 2 |

| Boxcab | 5100 | 1926 | 1 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S12 | 24-28 | 1953 | 5 |

| VO-1000 | 139-144, 5332-5333, 5337-5338 | 1941-1944 | 10 |

Electro-Motive Corporation/Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW7 | 11-13, 163-170 | 1950 | 11 |

| SW9 | 14-23 | 1950-1951 | 10 |

| SW1200 | 29-33, 100 | 1955-1957 | 6 |

| SW1 | 80-83, 5101-5105 | 1939-1950 | 9 |

| SW8 | 98, 99, 101 | 1951-1953 | 3 |

| NW2 | 145-162, 5302-5336 | 1939-1949 | 53 |

| NW5 | 186-195 | 1946 | 10 |

| SW1500 | 200-209 | 1967 | 10 |

| FTA | 252A, 256A-258A, 300A-305A, 300C-305C, 400A-428A (Evens), 400D-428D (Evens), 5600A, 5700A, 5701A, 5900A, 5900B | 1941-1945 | 51 |

| FTB | 252B-258B, 301B-305B, 400B-428B (Evens), 400C-428C (Evens), 5600B, 5700B, 5701B, 5900C | 1941-1945 | 46 |

| F3A | 225-231, 259A-267A, 259B, 262B-265B, 275A, 275B-276B, 306A, 306C, 350A-358A, 350C-358C, 375C-376C, 430A-438A (Evens), 430D-438D (Evens) | 1946-1948 | 56 |

| F3B | 260B-261B, 267B, 306B, 350B-358B, 430B-438B (Evens), 430C-438C (Evens) | 1948 | 23 |

| F7A | 268A-274A, 271B-275B, 275A-276A, 280A-281A, 307A-317A, 307C-317C, 350A, 360A, 364A-365A, 364C-365C, 444A-456A (Evens), 444D-456D (Evens), 460A-468A (Evens), 460D-468D (Evens) | 1949-1953 | 68 |

| F7B | 268B-270B, 280B-281B, 307B-309B, 311B-317B, 350B, 364B-365B, 380B-385B, 444B-468B (Evens), 444C-468C (Evens), 500B-504B | 1949-1953 | 45 |

| SDP40 | 320-325 | 1966 | 6 |

| SDP45 | 326-333 | 1967 | 8 |

| SD45 | 400-426 | 1966-1968 | 27 |

| F45 | 427-440 | 1969 | 14 |

| F9B | 470B-474B (Evens), 470C-474C (Evens) | 1954 | 6 |

| E7A | 500A-504A, 500B-504B, 510-512 | 1945-1947 | 13 |

| SD7 | 550-572 | 1952-1953 | 23 |

| SD9 | 573-599 | 1954-1958 | 27 |

| GP7 | 600-655 | 1950-1953 | 56 |

| GP9 | 656-734 | 1954-1959 | 79 |

| GP5 | 900-915 | 1958-1959 | 16 |

| GP20 | 2000-2035 | 1960 | 36 |

| GP30 | 3000-3016 | 1963 | 17 |

| GP35 | 3017-3040 | 1964-1965 | 24 |

| NC | 5100 | 1938 | 1 |

| NW1 | 5102 | 1938 | 1 |

| NW3 | 5400-5406 | 1939-1942 | 7 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U25B | 2500-2523 | 1964-1965 | 24 |

| U28B | 2524-2529 | 1966 | 6 |

| U33C | 2530-2544 | 1968-1969 | 15 |

| 44-Tonner | 5200-5201 | 1940 | 2 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A-1 Through A-11 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| B-1 Through B-22 | American | 4-4-0 |

| C-1 Through C-5 (Various) | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| D-2, D-4, D-5 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| E-1 Through E-15s | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| F-1 Through F-12 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| G-1 Through G-5 | Twelve-Wheeler | 4-8-0 |

| J-1 Through J-2s (Various) | Prairie | 2-6-2 |

| K-1, K-1s | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| L-1/s, L-2/s | Articulated | 2-6-6-2 |

| M-1, M-2 | Articulated | 2-6-8-0 |

| N-1 Through N-3 | Articulated | 2-8-8-0 |

| O-1 Through O-8 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| P-1, P-2 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| Q-1, Q-2 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| R-1, R-2 | Articulated | 2-8-8-2 |

| S-1, S-2 | Northern | 4-8-4 |

| Z-6 | Challenger | 4-6-6-4 |

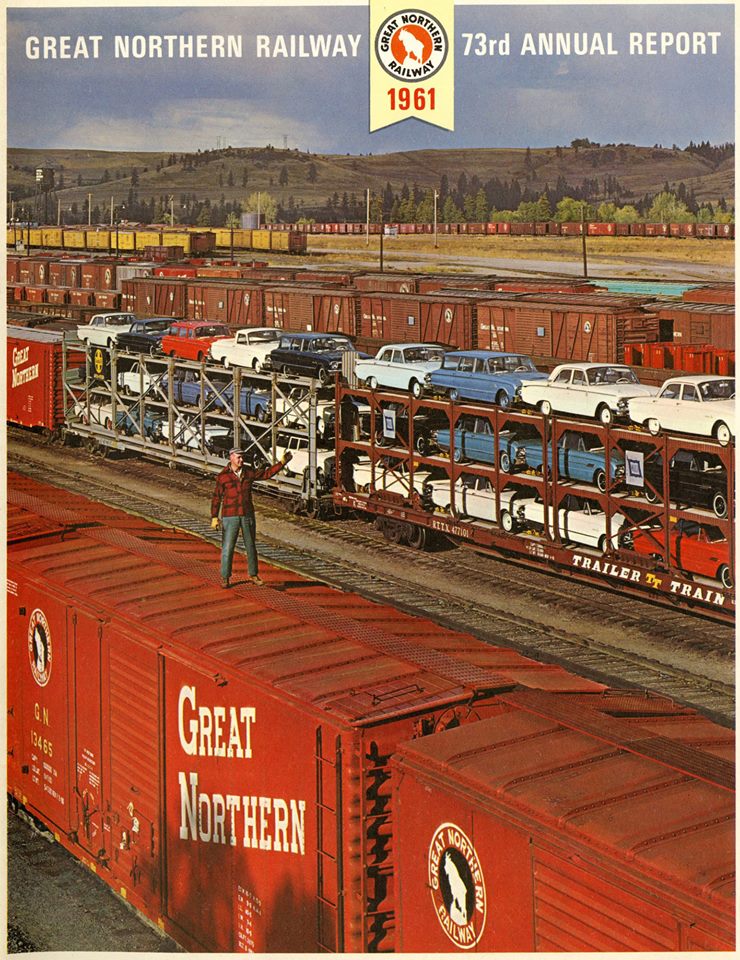

The front cover of Great Northern's 73rd Annual Report (1961). The caption reads: "A 'bright spot' in Great Northern's 1961 traffic picture, as illustrated on our colorful cover photo, was the rapidly rising volume of new automobiles riding the rails on multi-level rack cars. The scene is at Hillyard Yard, in Spokane, Washington. Tri-level racks, shown here, carry 12 standard and 15 compact autos. More than 3,000 multi-level carloads moved on Great Northern freight trains during the year."

The front cover of Great Northern's 73rd Annual Report (1961). The caption reads: "A 'bright spot' in Great Northern's 1961 traffic picture, as illustrated on our colorful cover photo, was the rapidly rising volume of new automobiles riding the rails on multi-level rack cars. The scene is at Hillyard Yard, in Spokane, Washington. Tri-level racks, shown here, carry 12 standard and 15 compact autos. More than 3,000 multi-level carloads moved on Great Northern freight trains during the year."Final Years

The traffic renaissance of World War II also brought further profits; tonnage soared to 59.7 million and net income reached as high as $29.1 million in 1942. Afterwards, GN continued posting strong numbers with a net annual income typically ranging from between $18 to $37 million.

In August of 1957 steam made its final revenue run as officials turned their focus to traffic diversification. In 1954 the railroad entered the intermodal/trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) revolution when it began service between Duluth/Superior and the Twin Cities; less than a decade later (1963) TOFC was generating roughly $4 million annually.

During its last year of corporate independence (1969) the Great Northern earned a net income of $23.4 million. In 1955 talks had been launched again between the three allying railroads about merging the "Hill Lines."

This led to a formal application filed with the Interstate Commerce Commission on February 17, 1961 which would bring together the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy into the previously-named conglomerate.

It would comprise 24,500 miles and include leasing the Spokane, Portland & Seattle for a period 10 years before its absorption into the parent company. In typical ICC fashion the process was slow and tedious. Finally, on March 31, 1966 the agency surprisingly voted against the merger in a 6-5 decision.

Undeterred the three railroads continued to push forward. A great hurdle was cleared when they worked out an agreement with the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific whereby their only transcontinental competitor was afforded eleven new western gateways.

Burlington Northern

This strategic opportunity provided the Milwaukee Road bountiful new sources of interchange traffic, particularly in conjunction with the Southern Pacific at Portland. With this issue resolved the ICC reopened hearings on January 4, 1967. Later that year, on November 30th, the merger was approved by an 8-2 vote.

As the process the railroad's name was formally changed to Burlington Northern, Inc. (BNI) during April of 1968. After overcoming a bit more legal work and objections the four railroads finally became one at 12:01 AM on March 2, 1970.

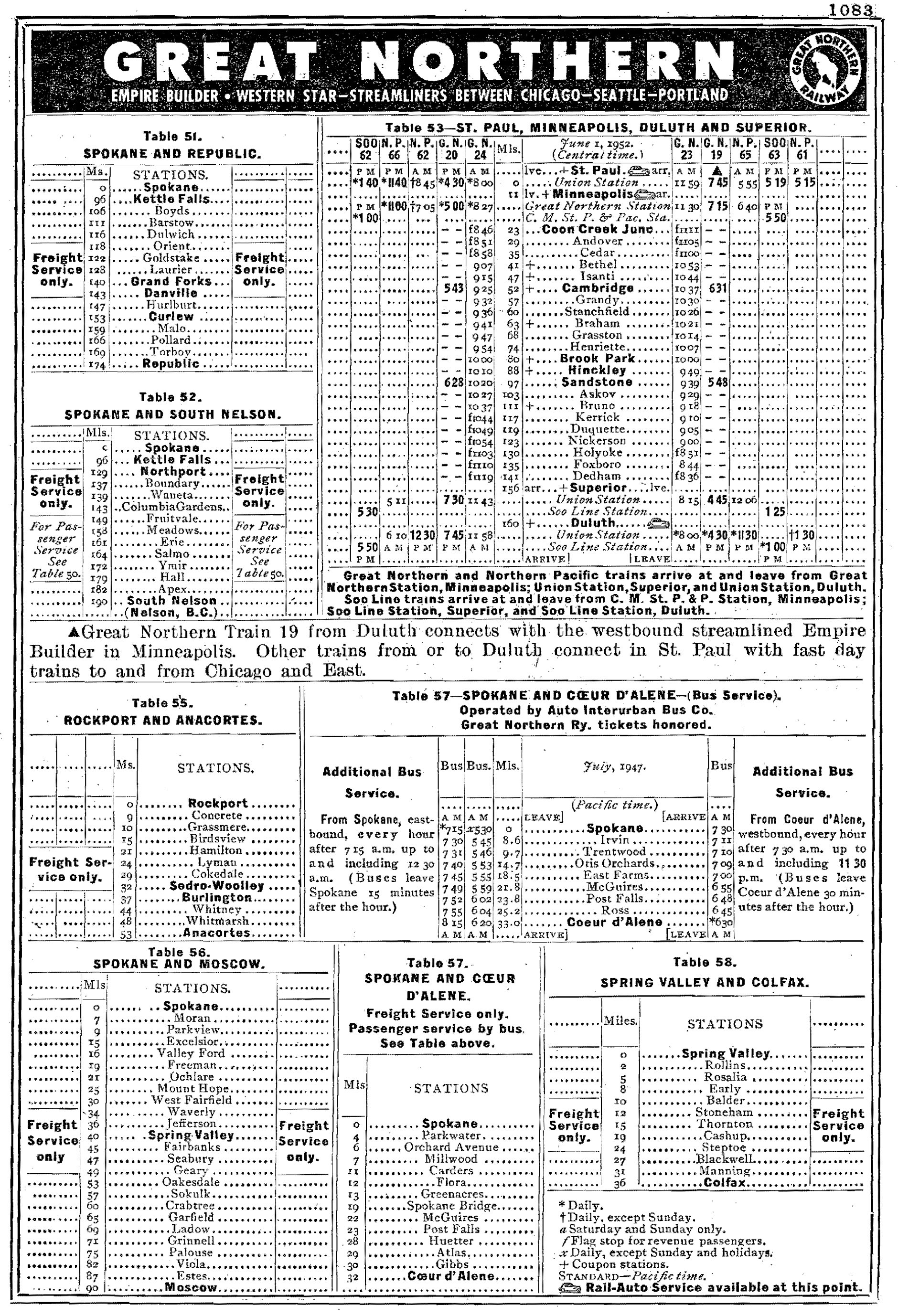

Public Timetables (August, 1952)

Recent Articles

-

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad. -

Delaware Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:23 PM

Delaware may rank 49th in state size but has a long history with trains. Today, a few museums dot the region. -

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here.