Grand Central Terminal (NYC), Manhattan's Historic Gem

Last revised: September 7, 2024

By: Adam Burns

New York Central's breathtaking Grand Central Terminal (GCT) is a New York City landmark and world famous station. It was built during the Golden Age of rail travel and exemplified the power and scope railroads wielded at that time.

While the terminal was a masterpiece of architecture and engineering, described as a gift to New York and a monument to the New York Central, it also had a very functional purpose.

Its development sprang up from a need to meet the rising demand of rail service during a time when no other mode of transportation could provide such fast and efficient service.

As Brian Solomon notes in his book, "Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals," GCT was built with the future in mind, designed to handle much more traffic than that which existed at the time it opened.

The history of rail service into downtown Manhattan can be traced well back into the 19th century. However, the current terminal was not completed until just prior to World War I.

As the traveling public abandoned trains for other modes of transportation in the post-World War II era the magnificent structure was in danger of being demolished.

However, in the wake of Penn Station's demise an outraged public thwarted these efforts and the building was eventually completely restored in the mid-1990s, reopening to the public in 1998.

The main concourse of Grand Central Terminal as it appeared just before the facility opened in 1913. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

The main concourse of Grand Central Terminal as it appeared just before the facility opened in 1913. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.New York City

No other railroad blanketed the greater New York City region like the mighty New York Central. Its predecessors provided the first rail service into Manhattan Island and once offered three main lines radiating northward near or out of the city.

At its peak the NYC boasted more than 11,000 route miles connecting Buffalo, Detroit, Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis.

In addition, its main line from New York to Buffalo, known as the Water Level Route, was the envy of the industry featuring an unprecedented four tracks while many of its other through routes were equipped with at least two tracks.

Only the equally prosperous Pennsylvania Railroad rivaled NYC's dominance in the East.

Each featured a main line radiating in different directions out of New York although they served many of the same markets, leading to a heated rivalry that lasted decades until the disastrous Penn Central merger of early 1968.

New York Central's earliest predecessor was the Mohawk & Hudson incorporated on April 17, 1826 and opened for service in August of 1831 between Albany and Schenectady.

Other early components included:

- Attica & Buffalo

- Auburn & Rochester

- Buffalo & Lockport

- Buffalo & Rochester

- Rochester & Syracuse

- Rochester, Lockport & Niagara Falls

- Schenectady & Troy

- Syracuse & Utica

- Tonawanda Railroad

- Utica & Schenectady

These small systems offered a through route from the state capital to Buffalo roughly following the Erie Canal.

According to Mike Schafer and Brian Solomon's book, "New York Central Railroad," they worked together in providing scheduled service between both cities.

As early as 1847 discussions commenced of a possible merger but the powerful canal lobby thwarted their idea.

Finally, led by Albany businessman Erastus Corning, who headed the Utica & Schenectady, the group received the blessing of the state legislature and formed the New York Central Railroad on May 17, 1853.

Corning was president of the NYC until after the Civil War and helped establish its eventual entry into Chicago.

South of Albany the NYC's ancestry lay in two principal lines, the New York & Harlem (NY&H) and Hudson River Railroad (HRRR).

The NY&H was the first railroad to serve Manhattan, chartered on April 25, 1831. It soon opened for service from 23rd Street to the Harlem River at the northern edge of the island running along roughly the east side nearer the East River.

As the city grew, service was extended further south beyond 23rd Street and subsequently pushed further north reaching Fordham in 1841, White Plains in 1844, neared the Connecticut and Massachusetts borders, and finally terminated at Chatham in 1852 129 miles away.

This latter town provided a connection with the Western Railroad, which served Massachusetts and later became part of the Boston & Albany (a future NYC subsidiary).

The other component was the Hudson River Railroad. This relative latecomer was chartered in 1842 by businessmen in Poughkeepsie concerned about the lack of rail service along the Hudson.

The HRRR was a difficult project, spearheaded by John Jervis (who built the Mohawk & Hudson), due to the rugged topography.

Despite numerous cuts, fills, and a few tunnels thanks to his engineering skills the grade was nearly level earning it the nickname "Water Level Route."

After seven years of construction (and several other obstacles, such as opposition from land owners and the NY&H), running northward from the west side of Manhattan the HRRR reached Peekskill in 1849 (40 miles) and Poughkeepsie by the end of that year. In 1851 service was finally opened to Albany along a 142 mile main line.

Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt

Enter Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose name remains synonymous with the New York Central. He was born in 1794 and at the age of 16 began his own ferry service between Staten Island and New York City.

Business savvy, Vanderbilt established a successful steamship operation and earned the title of Commodore by operating the largest schooner on the Hudson River.

He was worth a half-million dollars by 1834 and remained in the shipping industry for another three decades before realizing the future of transportation lay in the railroad.

In 1863 he acquired control of the New York & Harlem and a year later owned controlling interest in the Hudson River Railroad.

Through shrewd business practices the Commodore gained control of the original New York Central in 1867. He then formed a new company, the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad in 1869; the HRRR and NYC were merged into the new operation while the Harlem was leased.

Following this endeavor the Commodore quickly understood he would need a centralized passenger terminal in Manhattan.

Early Terminals

At the time of Vanderbilt's control the Harlem and HRRR served different terminals on the island, the latter had a facility at 30th Street while the former maintained a few depots over the years.

According to the New York Times article, "Before There Was A 'Grand' Central," by Christopher Gray (February 28, 2013) the NY&H once operated a terminal at Fourth Avenue and 26th Street designed by Robert Hatfield, which opened in 1845.

However, it caught fire in 1847 and was destroyed. A second was built at the northwest corner of 26th Street and 4th Avenue resembling an elongated castle fortress called "Madison Square Garden."

In 1857 the New York & New Haven opened its own depot nearby at the southwest corner of 4th Avenue and 27th Street and the two railroads shared a nearby yard.

As Schafer and Solomon point out in their book, more than streamlined service necessitated the need for a central station. In 1859 the city passed an ordinance banning steam locomotives south of 42nd Street, which meant the current facilities south of this point were essentially unusable.

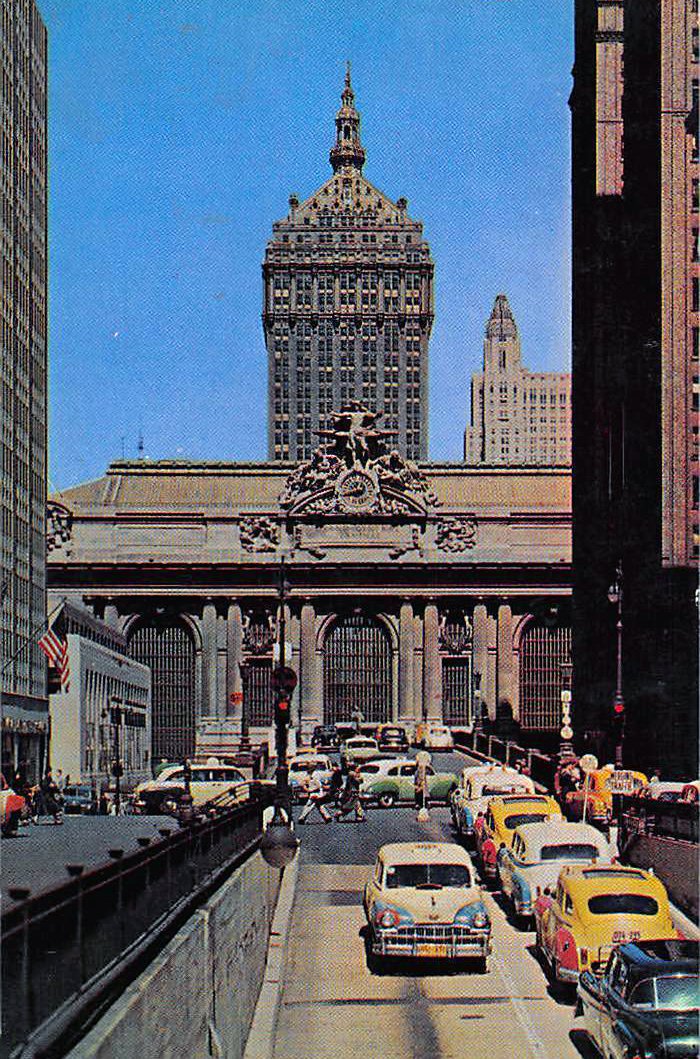

Grand Central Station as it appeared after its final rebuild circa 1906. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

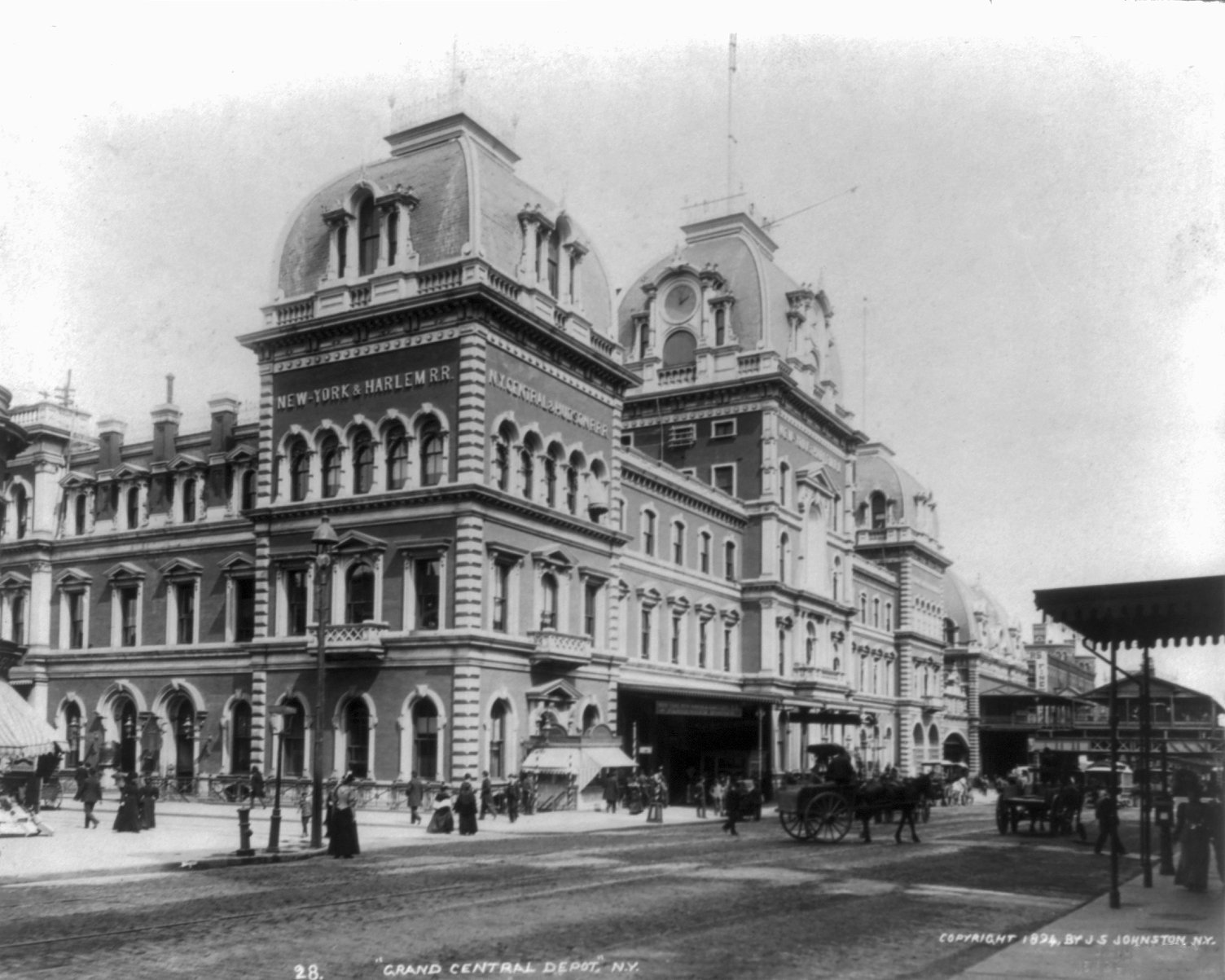

Grand Central Station as it appeared after its final rebuild circa 1906. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.Work began in 1869 for a new facility at 42nd and 4th Avenue, which at the time placed it on the outskirts of New York's downtown district.

The building was designed by architect John B. Snook with financial backing provided by Vanderbilt. It was a beautiful, multi-story structure designed in the French Second Empire style (also known as the French Renaissance style) and built from brick with stone trim.

There were also elements of London's St. Pancras Station employed, patterning a massive iron-and-glass train shed after this famous English terminal.

The structure was 600 feet long, 200 feet wide, and 100 feet tall capable of enclosing twelve tracks. The so-called Grand Central Depot handled trains of the Harlem, NYC&HR, and the New York & New Haven (a tenant) opening for service in October of 1871.

The Commodore had expected rail traffic to increase throughout the 19th century and designed the building accordingly; however, even he was likely shocked by just how rapidly New York grew after the Civil War.

After only a few years of operation the Depot was carrying out grade separation projects to handle increased commuter and passenger traffic and by the 1880s the facility was at-capacity.

Another project attempted to alleviate congestion by adding a second trainshed with seven tracks while a new passenger yard was put into service at nearby Mott Haven.

In a last-ditch effort a major renovation was carried out in 1898, which redesigned the existing building and added even more tracks to handle demand. With around 500 daily trains using the station by 1900 it was clear an entirely new facility was needed.

Excavation work is underway on the new Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan circa 1908. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

Excavation work is underway on the new Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan circa 1908. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.Construction

While planning was underway a devastating accident occurred inside the Park Avenue Tunnel on January 8, 1902 when an inbound train missed a stop signal and plowed into a fully loaded New Haven commuter train.

The cause was heavy smoke impairing the engineer's vision and the subsequent outcry banned steam locomotives throughout the city by July 1, 1908.

As early as 1899 the NYC&HR's chief engineer, William Wilgus, began studying electrification into the terminal. This plan was expedited after the accident.

The railroad eventually decided upon a design based from Baltimore & Ohio's successful electrification of its Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore using a 660-volt DC, "under-running" third-rail system (the energized rail was covered by a wood plank, which not only reduced accidental electrification but also kept debris or weather-related issues from fouling the system).

The project was launched in 1903 and opened for service on September 20, 1906 between Grand Central Station and High Bridge (7 miles).

In the succeeding three decades New York Central extended the network, including portions of the Harlem Line and Putnam Division. By 1931 it boasted around 70 route-miles of electrified territory.

A view of Grand Central's underground concourse taken in 1913 just before the facility opened. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

A view of Grand Central's underground concourse taken in 1913 just before the facility opened. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.During a 1903 competition architects submitted designs for the new Grand Central Terminal and the ultimate winner was Reed & Stem (Charles Reed and Allen H. Stem), a firm based out of St. Paul, Minnesota which had worked on several other railroad terminals.

There was also the hiring of Warren & Wetmore (Whitney Warren and Charles Wetmore) of New York City, which assisted on the massive project.

Much like Pennsylvania Station, Grand Central Terminal took years to complete, due largely to its many design changes and the need to keep the existing facility open during construction.

During this time architects planned far into the future. The building was constructed with few stairs, using instead ramps to keep traffic flow constant.

Charles Reed described these as "exterior circumferential elevated driveways." The few staircases which were incorporated into the structure were built very wide for the same purpose.

The architects even redesigned Park Avenue around the terminal! Reed would pass away in 1911 leaving Warren & Wetmore to finish the facility.

It was Charles Wetmore who is credited with Grand Central Terminal's colossal and breathtaking appearance, designed in the Beaux Arts style.

The exterior was dressed in Indiana limestone and Stony Creek granite while great sculptures adorned the main façade facing Park Avenue.

Depicted were the Roman gods and goddess Mercury, Minerva, and Hercules (carved by the John Donnelly Company) all of which surround a massive clock, 13-feet in diameter.

In addition are three towering windows, 33 feet wide and 60 feet tall, allowing sunlight to filter into the main concourse.

This open space itself is quite massive spanning 275 feet in length and 120 wide while the ceiling towers 125 feet over the floor at its tallest point. The concourse is perhaps the most photographed and best recognized area of the station.

Situated within its center is the information booth and sitting atop it is undoubtedly the building's most renowned feature, the four-faced clock; its faces, made of opal, are estimated to be worth between $15 and $20 million!

The canopy is not your ordinary ceiling. Artist Paul Cesar Helleu of France was hired to sculpt a work of art resembling the heavens when travelers looked skyward.

For added effect the stars featured in the scene were lit with small bulbs! Today, fiber optics is used. Another of the building's impressive engineer feats is its employment of an extra, lower-level concourse to separate commuters from long-distance travelers.

Here, located underground were 46 tracks in addition to a 70-acre rail yard. The foresight would prove invaluable (albeit the automobile was catching on about the time of GCT's opening) as the station would reach its peak use during World War II witnessing over 63 million travelers pass through its halls each year during 1945 and 1946.

Constellation Controversy

When the public first glimpsed Paul Helleu's masterpiece adorning GCT's ceiling it immediately drew awe and admiration. Unfortunately, it also caused controversy.

The constellations are very real but aside from Orion the entire scene depicts those seen in the Mediterranean region.

In addition, constellations Taurus and Gemini are both reversed in their relation to Orion in the night sky. No one has ever understood why the artist did this but the technical error has never been corrected over the years even during its major restoration of the 1990s.

When in the terminal be sure and look for the mural's dark patch. This oddity was left by restorers to show the amount of grime buildup left behind after decades of smoking inside the building!

The terminal had cost a total of $43 million but the price tag was justified considering the large volumes of traffic it handled.

At the stroke of Midnight on February 2, 1913, it opened for service and immediately witnessed a daily ridership of 68,700.

By the 1920s this number had doubled and following a downturn during the Great Depression era, peaked during the war.

Dozens of NYC's well known trains called at Grande Central, particularly during the streamlined era, the last great age of rail travel in this country.

These included names like the 20th Century Limited, Commodore Vanderbilt, James Whitcomb Riley, Knickerbocker, Lake Shore Limited, Pacemaker, Wolverine, and others.

The concourse is only one part of Grand Central Terminal. Another famous area is the Whispering Gallery where, due to the acoustics in the building, you can talk to another person by merely whispering, even with a rush of bustling people around you.

Also located in the station is its renowned and oldest business, the Oyster Bar. Besides the grandeur of the building's interior, the exterior is just as impressive. In spite of the building's magnificence it was in critical danger of being demolished after Penn Station fell in the 1960s.

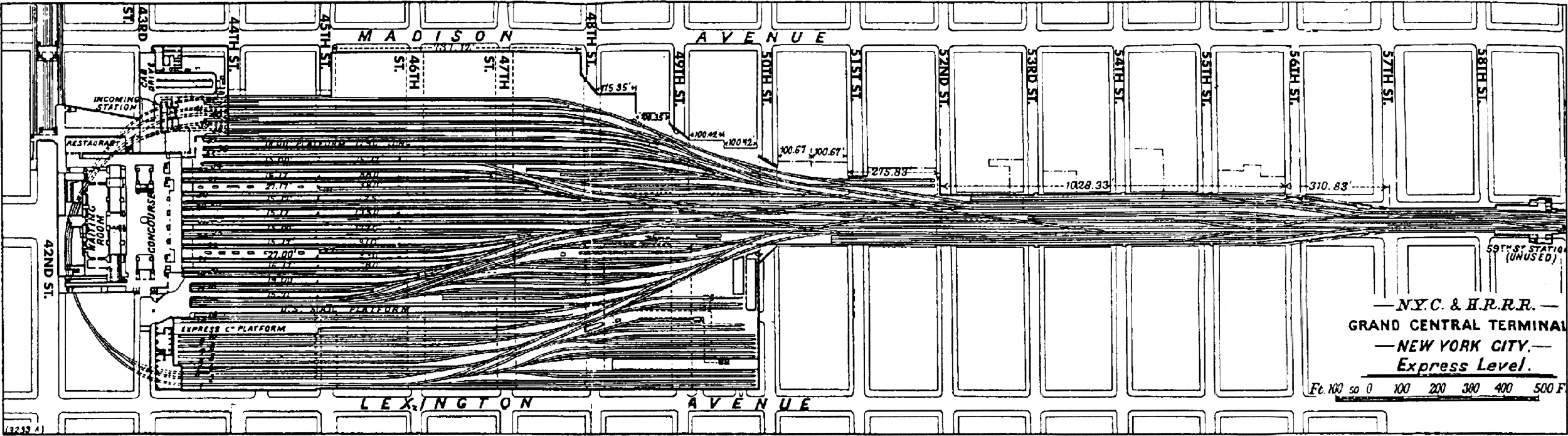

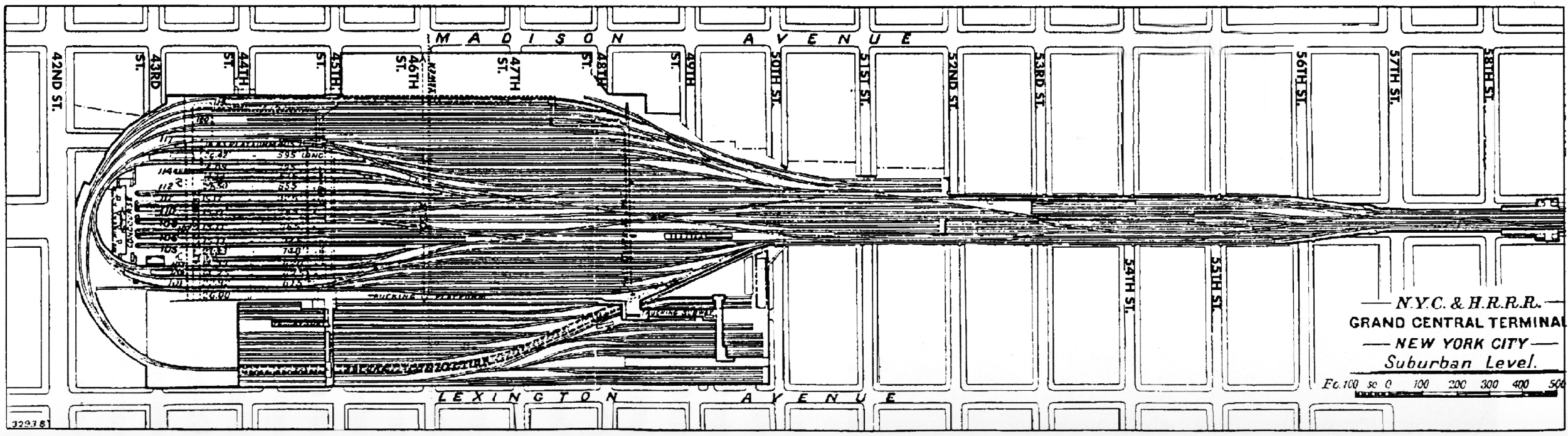

Track Layout

In an ironic twist the New York Central, the preeminent railroad to serve Manhattan, was eclipsed by the Pennsylvania Railroad when its old foe opened the first grand terminal in the city.

In late November of 1910 the breathtaking Pennsylvania Station was unveiled to the public, an architectural marvel built for the ages.

The PRR's facility arguably held a better overall design flow with through tracks connecting Long Island and the New Haven for service into New England.

By comparison Grand Central featured a quasi-stub end setup with the primary above-ground station serving as the southern terminus at East 42nd Street.

However, in reality, Grand Central Terminal was actually well-designed itself. The terminals engineers employed a labyrinth of track work beneath street-level to handle future traffic growth.

Their efforts paid off as even today the terminal has never exceeded the 100 million annual capacity for which it is designed.

The ingenious setup utilized loop tracks to largely eliminate the cumbersome issue of trains backing in and out of the terminal.

In addition, there were two levels to separate commuters from long-distance travelers; the upper level housed 42 tracks overall with a balloon track wrapping around 40 of these.

The lower level featured just 27 tracks but was circled by several balloon loops. In addition is the covert "Track 61."

This platform was constructed for VIP use beneath the Waldorf Astoria hotel and allowed personnel to slip in and out of town without ever being noticed.

It was first used by General John J. Pershing in 1938 and later used by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1944. It is reportedly still active today but much secrecy continues to surround Track 61. South of 96th Street, Grand Central's approach tracks are covered by Park Avenue.

The NYC leased the lucrative air rights over the right-of-way here which helped pay for the terminal project and the property values are some of the highest in the world.

To keep operations running efficiently and safely the New York Central constructed two of the largest interlocking towers ever built, Tower A (featuring 362 control levers) and Tower B with 400 levers.

Today, these facilities are closed and train movements are monitored via remote dispatching. When Grand Central Terminal opened in 1913 it witnessed nearly 22 million travelers a number that rose to over 40 million by the 1920s.

Its ridership peaked during World War II, as previously mentioned, and then slowly declined during the following two decades.

As of 2015, according to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Grand Central hosts more than 160,000 riders every weekday with more than 50 million each year.

Today

From the 1950s onward the terminal was not immune from America's ever-dwindling use of trains.

By the time the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad merged in 1968, to form the disastrous Penn Central Transportation Company, the building was falling into disrepair and witnessed only 138,500 daily travelers that year.

Penn Central, always desperate for whatever funds it could scrape together after its 1970 bankruptcy, sought numerous times to either destroy or alter Grand Central Terminal but was blocked in each attempt by the recently created Landmarks Preservation Commission.

This agency had been formed in 1965 after the PRR had successfully brought down its gift to the city, the mighty Pennsylvania Station, in an attempt to stave off growing deficits.

In a heated court battle with PC, the City of New York eventually won the fight when GCT was bestowed the greatest honor a building in this country can ever receive; in December of 1976, the National Register of Historic Places named Grand Central Terminal a National Historic Landmark forever preserving its future.

The west balcony of Grand Central Terminal's concourse as seen in 1913. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.

The west balcony of Grand Central Terminal's concourse as seen in 1913. Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company.The US Supreme Court also upheld the decision two years later. However, it would be another twenty years before efforts to return the structure to its former glory truly paid off.

In the mid-1990s the building was commissioned for a complete restoration and was rededicated on October 1st, 1998.

Today, Grand Central Terminal hosts thousands of daily commuters (Amtrak has not used the facility since 1991) operated by the Metro-North Railroad and is a popular tourist attraction with shops, restaurants, and various entertainment venues.

Since 2007 a large-scale tunneling project has been underway to provide Long Island Rail Road commuters service into GCT and is expected to open between 2019 and 2023. Grand Central Terminal is an impressive and awing building, regardless of your interest in trains.

So, if you get the chance when in New York, please take a moment and visit this glorious building, you will surely be glad that you did!

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Maryland Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 01:36 PM

The state of Maryland is where it all began with the Baltimore & Ohio. Along with the B&O Railroad Museum, several other similar organizations can be found in the state. -

Maine Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 12:58 PM

Maine's railroads have long been associated with logging and agriculture. Today, a number of museums honoring this heritage can be found throughout the state. -

Kentucky Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 20, 25 03:17 PM

Kentucky has long contained a mix of important through main lines and rich bituminous coal seams for the railroad industry. Today, a handful of museums can be found across the state.