Erie Railroad: Map, Passenger Trains, Logo, History

Last revised: October 11, 2024

By: Adam Burns

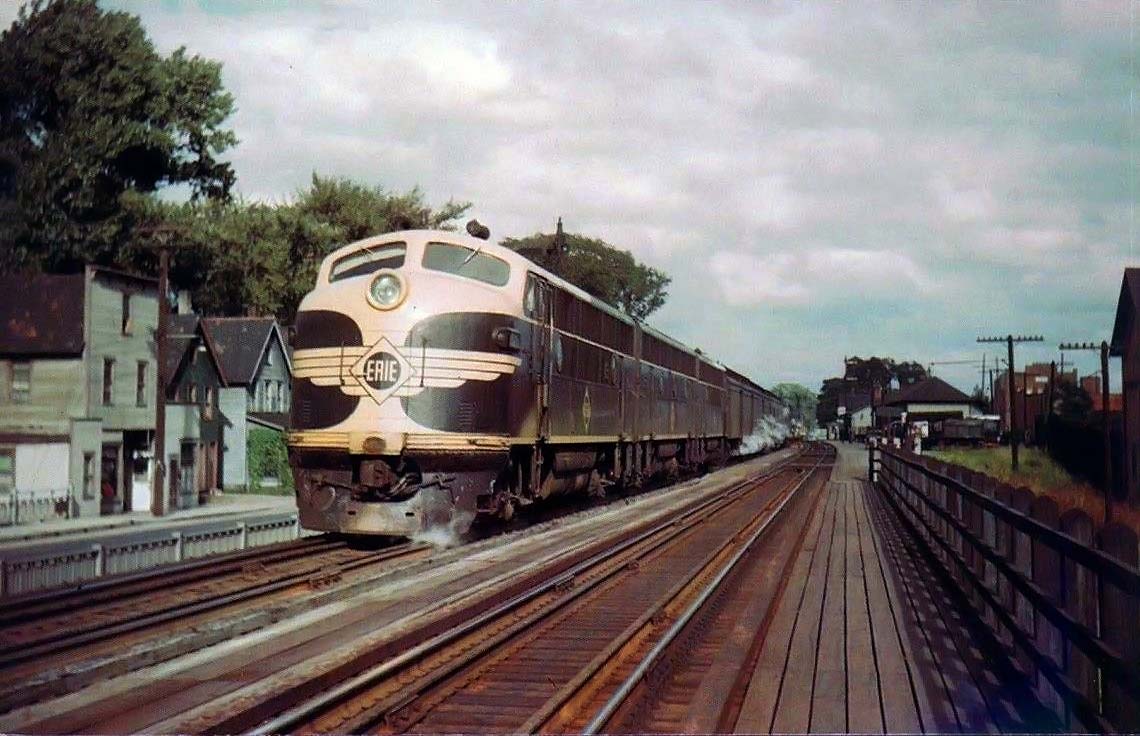

The Erie Railroad was once the fourth way to Chicago, a sometimes forgotten competitor in the hotly-contested market from New York to the Windy City. Its network was much smaller than either the Pennsylvania, New York Central, or Baltimore & Ohio.

However, it boasted a high and wide, double-tracked main line, a routing that would prove ideal in handling today's profitable intermodal business.

The Erie's history began during the industry's earliest days and was once a dominant eastern carrier during the 19th century.

As the 20th century progressed, laden with increasing debt and multiple reorganizations the Erie sought a merger partner, eventually joining the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western to form Erie-Lackawanna in 1960.

An EL in today's world would have been a successful enterprise but alas its debt, competition against Penn Central, and restrictive government regulations helped bring down the company in the early 1970s.

Today, segments of the old Erie system remain in use east of Ohio but most of its network is abandoned west of that point.

Photos

Erie Railroad F3A #802 and other power layover at engine terminal in Hammond, Indiana on August 24, 1958. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Railroad F3A #802 and other power layover at engine terminal in Hammond, Indiana on August 24, 1958. Photographer unknown. American-Rails.com collection.History

The classic Erie Railroad had a fascinating, if not tumultuous, corporate history which allowed it to witness the birth of the industry through the creation of Conrail in 1976. The company's beginnings are thanks, in part, to the Erie Canal.

As the most famous and successful transportation waterway ever built in the United States, the canal ran across New York state. It began construction in 1817 and eventually connected Albany, along the Hudson River, with Buffalo spanning a distance of more than 360 miles.

It opened for service on October 26, 1825. During this era canals were regarded as the future of efficient transportation but they did have issues; the waterways were expensive to build, moved freight and people slower than a stagecoach, and the northern hemisphere froze solid during colder months of the year (roughly November through March/early April). As a further setback, railroads were already in development at the time.

At A Glance

6 feet (1841-1874) 4 Feet, 8 ½ Inches (1874-1960) | |

2,736.67 (1930) 2,341 (1950) |

|

Jersey City - Paterson - Middletown - Hornell - Youngstown - Chicago Marion - Dayton - Cincinnati, Ohio Hamilton, Ohio - Indianapolis, Indiana Leavittsburg - Cleveland, Ohio Pymatuning, Pennsylvania - Leavittsburg, Ohio Hornell - Buffalo - Niagara Falls, New York Salamanca - Dunkirk, New York Corning - Attica - Avon - Rochester, New York River Junction - Cuba Junction, New York Carrolton - Eleanora Junction, New York Corning, New York - Newberry Junction, Pennsylvania Lanesboro - Wilkes-Barre/Scranton, Pennsylvania Lackawaxen - Avoca, Pennsylvania Newburgh Junction- Campbell Hall - Graham, New York Maybrook - Pine Island, New York Croxton - Nyack, New York Piermont - Suffern, New York New York & New Jersey Junction, New Jersey - Nanuet, New York Rutherford Junction - Ridgewood Junction Paterson - Newark, New Jersey Croxton - Midvale, New Jersey |

|

Diesels: 695 |

|

Freight Cars: 20,372 Passenger Cars: 519 |

|

With the Erie Canal's completion the state's Southern Tier region (the block of counties running along the border with Pennsylvania from Delaware to Chautauqua County) felt their economic fortunes would seriously erode if they, too, did not have a better means of transportation.

This prompted Governor Enos Thompson Throop to charter the New York & Erie Rail Road on April 24, 1832 to connect Piermont, along the Hudson River, with Dunkirk situated along Lake Erie.

Logo

Railroading of this period was an odd, extremely selfish industry as promoters (or even state legislatures) obsessed over the possibility that another might invade their territory or undercut their system's future prospects.

Incredibly, the idea of interchange and partnership with another road was not of great concern and actually frowned upon. In the case of the NY&E its charter also stipulated it must be built to broad gauge (6 feet) as a further step of interchange prevention and was not allowed to lay rails outside its home state.

Erie's train #7, the westbound "Pacific Express" (Jersey City - Chicago), makes its afternoon stop in Warren, Ohio during the summer of 1949. William Rinn photo.

Erie's train #7, the westbound "Pacific Express" (Jersey City - Chicago), makes its afternoon stop in Warren, Ohio during the summer of 1949. William Rinn photo.As the railroad pushed west it ultimately had no choice but to run a grade through the northeastern tip of Pennsylvania on its way to Binghamton (such as Lackawaxen and Susquehanna) to utilize the best route in an otherwise rugged region.

Construction officially began in 1836 and was completed from Piermont to Goshen (about 40 miles) on September 23, 1841. It continued due west to Port Jervis and wound its way along the Delaware River before turning away at Deposit, New York aiming for Binghamton.

In the process, it constructed one of the great feats in engineering at Lanesboro, Pennsylvania, the Starrucca Viaduct. It was designed by Julius W. Adams and James P. Kirkwood as a beautiful stone-arch structure spanning Starrucca Creek.

The bridge was 1,040 feet in length and capable of handling two tracks. It opened for service in 1848 and today is a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark that still witnesses rail traffic.

Erie Railroad 2-8-4 #3376 (S-3) steams west across the Hackensack River at Secaucus, New Jersey on October 18, 1951. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Railroad 2-8-4 #3376 (S-3) steams west across the Hackensack River at Secaucus, New Jersey on October 18, 1951. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.In 1847 the NY&E opened to Binghamton, 207 miles from Piermont, and finally completed its 447-mile main line in the spring of 1851. According to H. Roger Grant's authoritative title, "Erie Lackawanna: Death Of An American Railroad, 1938-1992," the first train of dignitaries ran the entire length of the system on April 22nd that year.

The Erie was the jewel of New York and was the only railroad at the time to boast a route of its length under common ownership.

A year later, it acquired two small lines, the Paterson & Hudson River Rail Road and Paterson & Ramapo Railroad, to reach Jersey City, New Jersey via Suffern, New York.

At Jersey City, the Erie went on to construct Pavonia Terminal along the Hudson River to provide ferry service into downtown Manhattan. It remained in service until late 1958 when the railroad began using Delaware, Lackawanna & Western's nearby and much larger, Hoboken Terminal.

Erie 4-6-2 #2544 working suburban service at Spring Valley, New York; April 18, 1953. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie 4-6-2 #2544 working suburban service at Spring Valley, New York; April 18, 1953. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.Alas, in some ways the opening of NY&E's original route proved its zenith. Further growth stalled for years and it slowly fell behind competitors racing towards the Midwest as the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, and what later became the New York Central passed it by.

Its original end points were of little value; Piermont did not development into a market of any considerable size while Dunkirk did not have a deep water port.

Realizing it needed a connection to the growing city of Buffalo it reached the location in 1853, as well as nearby Rochester, via branch lines from its main stem.

In 1859 it entered into the first of five bankruptcies, emerging as the Erie Railway on June 25, 1861. The 1860s also witnessed a prolonged battle for control of the company; in the so-called "Erie War" of 1867, sparked by Cornelius Vanderbilt of the New York Central, the Commodore fought with Daniel Drew, Jay Gould, and Jim Fisk for stakes in the railroad.

In the end, Gould gained control (1868) and during his four years did his best to improve the shabby property and continue expansion westward.

In 1872, Gould was fired as president although he did acquire control of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad for a time, which eventually joined the Erie system.

General Electric's experimental A-B-B cab unit set #750, the UM20B (missing is the second A unit, trailing is an FA), seen here at Salamanca, New York testing in Erie Railroad colors during the 1950's. In 1959 the group was purchased by Union Pacific. John Bartley photo.

General Electric's experimental A-B-B cab unit set #750, the UM20B (missing is the second A unit, trailing is an FA), seen here at Salamanca, New York testing in Erie Railroad colors during the 1950's. In 1959 the group was purchased by Union Pacific. John Bartley photo.Mike Schafer notes in his book, "More Classic American Railroads," the road was again in receivership during the 1870s when it emerged as the New York, Lake Erie & Western in 1878.

In 1874 the company gained new leadership through Hugh Jewett (through 1884), who oversaw the conversion to standard gauge of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches, which was widely becoming the industry standard.

By that time, self-interests had waned and any railroad hoping to enjoy a prolonged future had to seamlessly interchange with its surrounding neighbors, competitors or otherwise.

The aforementioned A&GW, after various bouts of lease agreements with the Erie and a reorganization that saw its name changed as the New York, Pennsylvania & Ohio, was finally under the road's control by the 1883 which gave it new markets throughout Ohio including Akron, Cleveland, and Cincinnati.

The NYLE&W's last great expansion also occurred at this time when it acquired the Chicago & Atlantic Railway that same year (1883).

The C&A had opened a 250-mile route from Marion, Ohio to Hammond, Indiana while trackage rights over the Chicago & Western Indiana provided it access into Chicago and, later, Dearborn Station.

Mr. Grant notes that the C&A was arguably the best engineered route across Indiana and became well recognized for this attribute in later years. In 1884, new president John King (through 1894) oversaw the final hints of expansion by completing coal branches into the northern and central regions of Pennsylvania.

This, for the most part, completed the NYLE&W's network that stretched 2,166 miles from Jersey City to Chicago, including all branches.

The financial panic of 1893 resulted in the road's third bankruptcy where it was reorganized as the Erie Railroad. By this time the company was acquiring an increasing level of debt and was further burdened by high interest rates.

These issues plagued the road throughout the 20th century, resulting in a limited borrowing power and slighted names like the "Weary Erie" with the statement, "It ran Nowhere-In-Particular to Nowhere-At-All." But, things looked up after Frederick Underwood became president in 1900.

Erie 2-8-4's double-head a long freight west, bound for Chicago, through northern Indiana during the 1950s. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie 2-8-4's double-head a long freight west, bound for Chicago, through northern Indiana during the 1950s. Ed Olsen photo. American-Rails.com collection.He spent massively on infrastructure improvements, including the complete double-tracking of its Chicago main line. The route through the Hoosier State was of particular interest as it was grade separated in many locations, often yards apart.

Underwood purchased new locomotives, launched time freights to Chicago, avoided bankruptcy through innovative financing, and installed Automatic Block Signals (ABS).

During the 1920s the railroad was acquired by the Van Sweringen brothers who saw the Erie's valuable Chicago route as a great addition in their growing empire (they also controlled the Chesapeake & Ohio, Denver & Rio Grande Western, and Pere Marquette among others).

They had likely intended to eventually merge their eastern properties into one system, which would have rivaled the other eastern trunk lines. Unfortunately the brothers passed away in the 1930s so it is hard to tell just how the Northeast rail map would have appeared had they lived long enough to carry out their plans.

System Map (1930)

The Great Depression of 1929 and resulting economic downturn of the 1930s began a long road of decline for the Erie. This resulted in a fourth bankruptcy in 1938 where the company emerged on December 22, 1941 carrying the same name.

It did witness a bright spot during World War II, where the great influx of wartime traffic and the profits it brought enabled the company to pay down much of its long term debt.

It also carried out infrastructure improvements, such as acquiring new diesel locomotives and retiring its fleet of maintenance-intensive steamers.

The Erie had recognized the diesel's potential early, acquiring its first boxcab in 1926 and worked hard through the 1940s and 1950s to complete the upgrade of its motive power fleet.

The road, "Serving The Heart Of Industrial America," was a good company with a competitive main line that carried a high and wide right-of-way, devoid of clearance impediments, thanks to its broad gauge heritage. The industry's leading railroads recognized this status, despite its financial woes.

Erie Railroad 4-6-2's lined up at Waldwick, New Jersey following their afternoon commuter runs on October 23, 1949. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Railroad 4-6-2's lined up at Waldwick, New Jersey following their afternoon commuter runs on October 23, 1949. Bob Collins photo. American-Rails.com collection.Alas, as the 1950s progressed this was of little consolation. It worked hard to offset traffic losses by encouraging industrial development along its property and launched new trailer-on-flatcar service (TOFC) during July of 1954.

The late-era Erie operated over 2,300 route miles while its Chicago-New York main line was 998 miles in length.

Its passenger services were respectable with names like the Erie Limited (its flagship, the train pampered guests with Pullman parlor-buffets, deluxe coaches, dining service, and sleepers) and Lake Cities but with a schedule of around 24 hours they could not compete with the fast, 16-hour times offered by the New York Central and Pennsylvania.

However, freight was another matter and the road handled a variety from anthracite coal and general merchandise to perishables and expedited movements.

Its few feeder branches proved both a blessing and a curse; the lack of online traffic hurt it considerably although after World War II proved an advantage when these superfluous secondary corridors helped bring down many roads in the Northeast and New England.

Erie Railroad GP7 #1239, RS3 #920, and RS2 #950 have an outbound commuter run from Hoboken Terminal at Croxton, New Jersey, circa 1958. The train is passing beneath Tonnelle Avenue as it moves away from the photographer, exiting off the Lackawanna main line and onto Erie's Northern Branch. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Railroad GP7 #1239, RS3 #920, and RS2 #950 have an outbound commuter run from Hoboken Terminal at Croxton, New Jersey, circa 1958. The train is passing beneath Tonnelle Avenue as it moves away from the photographer, exiting off the Lackawanna main line and onto Erie's Northern Branch. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.As freight evaporated thousands of miles of this trackage became redundant and companies like the Lehigh Valley, Reading, Boston & Maine, and New Haven all went bankrupt.

Realizing the wartime traffic boom was a mirage, in 1954 the Erie began informal talks with the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western regarding the possibility of merger.

Erie/EL GP7s #1235 and #1234 layover at Portland, Pennsylvania on February 5, 1967. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie/EL GP7s #1235 and #1234 layover at Portland, Pennsylvania on February 5, 1967. American-Rails.com collection.Passenger Trains

Erie Limited: Connected Jersey City with both Buffalo and Chicago.

Lake Cities: Connected Jersey City with Cleveland, Buffalo, and Chicago.

Pacific Express: (Jersey City - Chicago)

Atlantic Express: (Chicago - Jersey City)

Midlander: (Jersey City - Chicago)

Southern Tier Express: Connected Buffalo with Hornell and Jersey City.

Mountain Express: (Jersey City - Hornell)

Tuxedo: (Jersey City - Port Jervis)

The DL&W had been a finely managed property throughout its history and until the Great Depression earned handsome profits.

To cut losses they launched joint operations in various locations; on October 13, 1956 the Erie began using Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal for commuter services, ending all services from its Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City on December 12, 1958.

In addition, the two began sharing trackage between Binghamton and Gibson, New York, via the Erie's main line, in 1957. On September 10, 1956 studies were launched regarding a merger between the Erie, DL&W, and Delaware & Hudson. On April 13, 1959 the D&H dropped out but the other two roads continued on.

A pair of Erie's handsome 2-8-4's await their next assignment at the road's Marion, Ohio terminal in April, 1947. The lead unit, #3331 (S-2), was manufactured by Lima in 1927. The railroad owned some 105 Berkshires and all were scrapped between 1950-1952.

A pair of Erie's handsome 2-8-4's await their next assignment at the road's Marion, Ohio terminal in April, 1947. The lead unit, #3331 (S-2), was manufactured by Lima in 1927. The railroad owned some 105 Berkshires and all were scrapped between 1950-1952.Erie Lackawanna

During the next year the process worked its way forward until the Interstate Commerce Commission formally approved the union on September 13, 1960. The new Erie-Lackawanna Railroad (EL) officially began operations on October 17, 1960 with an entire network of 3,031 miles.

The EL was not particularly successful, losing millions right from the start, despite a consultant's many studies to the contrary. The deepening recession after 1958 had made matters worse, ballooning the predecessor roads' debt, which combined totaled twenty-two outstanding bonds!

In 1963 the company gained new leadership under Bill White and he worked wonders to stave off bankruptcy and improve earnings until his unexpected passing in early 1967.

Erie Railroad RS3 #928 works suburban service on the Caldwell Branch at Caldwell, New Jersey, circa 1955. This short spur ran just 5.8 miles according to the 1954 "Official Guide." It swung off the Greenwood Lake Branch (ex-New York & Greenwood Lake Railway) at Great Notch and ran as far as Essex Falls, via Caldwell. The line was largely embargoed following a washout in 1975 and removed in 1981. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Erie Railroad RS3 #928 works suburban service on the Caldwell Branch at Caldwell, New Jersey, circa 1955. This short spur ran just 5.8 miles according to the 1954 "Official Guide." It swung off the Greenwood Lake Branch (ex-New York & Greenwood Lake Railway) at Great Notch and ran as far as Essex Falls, via Caldwell. The line was largely embargoed following a washout in 1975 and removed in 1981. Meyer Pearlman photo. American-Rails.com collection.The EL was faced with several setbacks which all came in quick secession after 1968; first, the creation of the disastrous Penn Central merger and its 1970 collapse resulted in service disruptions and loss of traffic.

Two years later, Hurricane Agnes hit in June of 1972 which dealt EL a fatal blow, wreaking havoc on its property and forcing it into bankruptcy (its fifth, and final, receivership).

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boxcab | 20 | 1926 | 1 |

| HH-660 | 302-305 | 1939 | 4 |

| S1 | 306-321 | 1946-1950 | 16 |

| S2 | 500-525 | 1946-1949 | 26 |

| S4 | 526-529 | 1951-1952 | 4 |

| FA-1 | 725A-735A, 725D-735D | 1947-1949 | 22 |

| FB-1 | 725B-735B, 725C-735C | 1948-1949 | 22 |

| FA-2 | 736A-739A, 736D-739D | 1950-1951 | 8 |

| FB-2 | 736B-739B, 736C-739C | 1950-1951 | 8 |

| PA-1 | 850-861 | 1949 | 12 |

| PA-2 | 862-863 | 1951 | 2 |

| RS2 | 900-913, 950-954 | 1949 | 19 |

| RS3 | 914-933, 1005-1038 | 1950-1953 | 54 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DS-4-4-660 | 381-385 | 1946-1949 | 5 |

| DS-4-4-750 | 386-389 | 1949 | 4 |

| DS-4-4-1000 | 600-601 | 1946 | 2 |

| S12 | 617-628 | 1951-1952 | 12 |

| LS-1000 | 650-659 | 1949 | 10 |

| DRS-4-4-1500 | 1100-1105 | 1949 | 6 |

| AS16 | 1106-1120, 1140 | 1951-1952 | 16 |

| DRS-6-6-1500 | 1150-1161 | 1950 | 12 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW1 | 360 | 1948 | 1 |

| NW2 | 401-427 | 1939-1949 | 27 |

| SW7 | 428-440 | 1950-1952 | 13 |

| FTA | 700A-705A, 700D-705D | 1944 | 12 |

| FBA | 700B-705B, 700C-705C | 1944 | 12 |

| F3A | 706A-710A, 706D-710D, 800A-806A, 800D-806D | 1947-1949 | 24 |

| F3B | 706B-710B, 706C-710C, 800B-806B | 1947-1949 | 17 |

| F7A | 711A-712A, 711D-712D, 807A, 807D | 1950-1951 | 6 |

| F7B | 711B-712B, 711C-713C, 807B | 1950-1952 | 6 |

| E8A | 820-833 | 1951 | 14 |

| GP7 | 1200-1246, 1400-1404 | 1950-1952 | 52 |

| GP9 | 1260-1265 | 1956 | 6 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44-Tonner | 26 | 1946 | 1 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| C1 Through C3 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| H20 Through H22 (Various) | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| J1, J2 | Decapod | 2-10-0 |

| K1 Through K5 (Various) | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| L1 | Articulated | 0-8-8-0, 2-8-8-2 |

| M1 | Articulated | 2-6-8-0 |

| N1 Through N3 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| P1 | Articulated | 2-8-8-8-2T (Triplex) |

| R1 Through R3 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| S1 Through S4 | Berkshire | 2-8-4 |

A brand new set of Erie Railroad F3's, led by #805-A, in Chicago with a passenger train during August, 1947. Author's collection.

A brand new set of Erie Railroad F3's, led by #805-A, in Chicago with a passenger train during August, 1947. Author's collection.Conrail

On May 8, 1974 the Pougkeepsie Bridge, which spanned the Hudson River burned and was severely damaged. This bridge had long been an important interchange with New England carriers like the New Haven, but owner Penn Central refused to make repairs.

Finally, already in a precarious financial situation and unable to work out a deal with its unions for inclusion into the Chessie System (Chessie would have utilized all lines east of Sterling, Ohio) the company decided to join the new Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail).

The new railroad had little need for a third main line to Chicago and soon abandoned or sold the former corridor across Indiana and western Ohio after 1977.

There were a few attempts by short line operators to preserve this trackage but lack of customers resulted in its complete abandonment during the early 1980s.

Today, Erie's superior double-track main line across the Heartland has been largely returned to nature, plowed under for agriculture purposes.

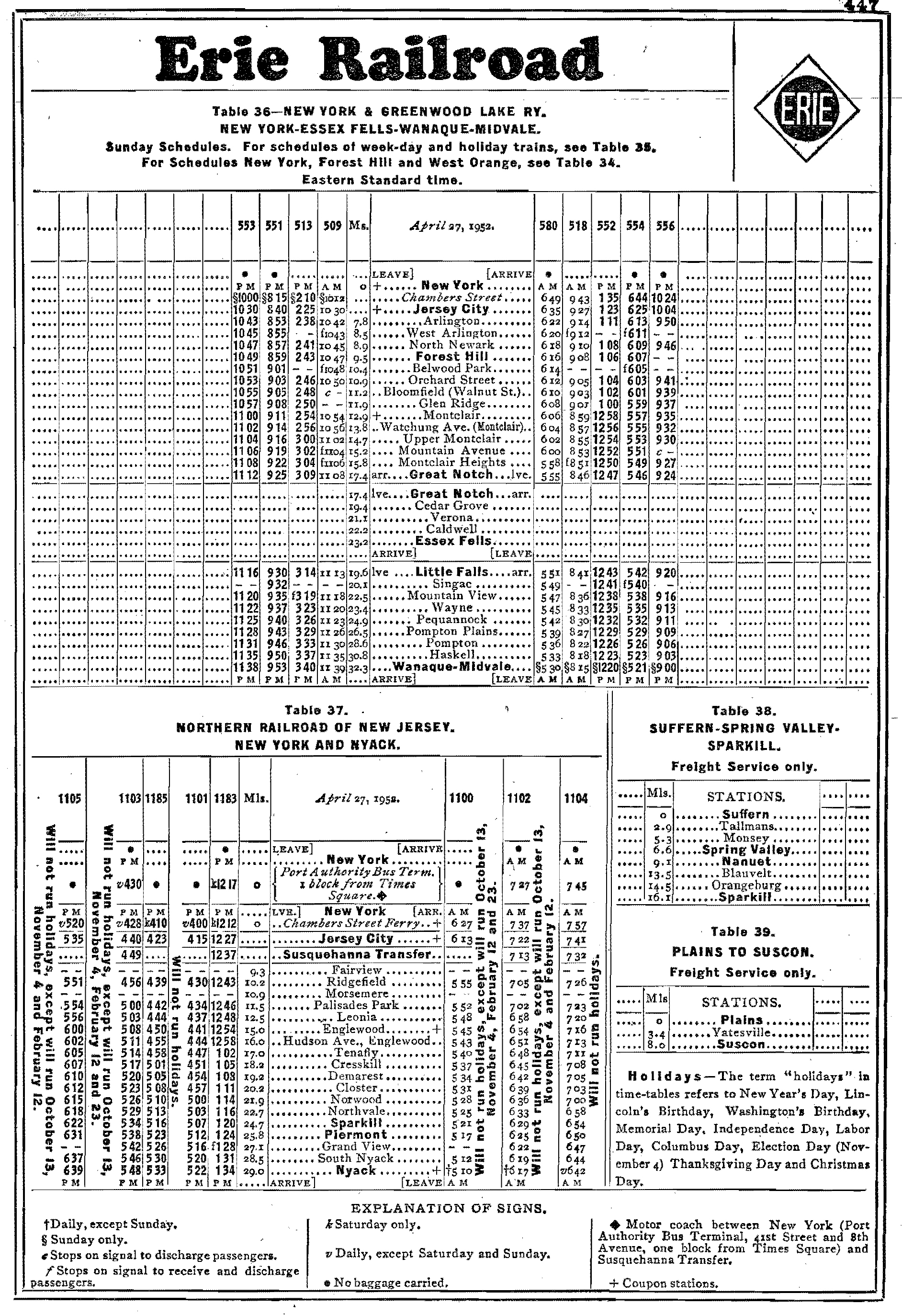

Timetables (August, 1952)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive. -

Rio Grande K-27 "Mudhens" (2-8-2): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 05:40 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-27 of 2-8-2s were more commonly referred to as Mudhens by crews. They were the first to enter service and today two survive. -

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved.