Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad: Map, Roster, History

Last revised: July 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad carried an interesting, "rags to riches" history. Its earliest component can be traced back to the late 1840's although the modern system did not appear until some decades later.

What began as a narrow-gauge coal hauler was transformed into a profitable auto parts carrier. The company's early years were fraught with bankruptcy as various owners strung together segments of rickety, poorly built railroad across western Ohio.

During the 1920's, Henry Ford became interested and everything changed. The legendary Detroit automaker, seeing potential in the DT&I, was able to turn the moribund property into a money-maker within only a few years.

Ford's ownership lasted less than a decade but he brought much needed capital, stability, and vision.

History

These attributes put the company on solid footing for the rest of its days. As the merger movement heated up during the 1960's the DT&I found itself with ever-fewer interchange partners.

After Penn Central's collapse it managed to persevere for a decade as an independent but was eventually purchased by the Grand Trunk Western in 1980.

Today, most of the remaining DT&I network is operated by Indiana & Ohio, a division of Genesee & Wyoming.

Photos

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40 #404 awaits departure from Flat Rock, Michigan in September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40 #404 awaits departure from Flat Rock, Michigan in September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.Iron Railroad

What became the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton was a patchwork of predecessors and new construction. It all began with the Iron Railroad, incorporated on March 7, 1849. For many years this system, built to Ohio's Broad Gauge of 4 feet, 10 inches, had no direct ties to the DT&I.

It was laid down between 1849 and December of 1851 from the small town of Ironton, Ohio along the Ohio River where it extended northward to Center Furnace, a distance of 13 miles. The little pike was primarily built to transport local iron ore, timber, limestone, and charcoal in the production of pig iron at Ironton.

It attempted to push further north and establish an interchange with the standard-gauge (4 feet, 8 1/2 inches) Belpre & Cincinnati (a future component of the Baltimore & Ohio) but lack of funds curtailed the project.

It finally achieved an outside connection when the Toledo, Delphos & Burlington opened at Dean (near Center Furnace) in January of 1883.

Overview

3 Feet (July 18, 1878 - December 31, 1879) 4 Feet, 8 ½ Inches (January 1, 1880 - January 1, 1984) | |

Detroit - Springfield, Ohio - Ironton, Ohio Jackson - Coalton - Cornelia, Ohio Kingman - Jeffersonville - Sedalia, Ohio Petersburg, Michigan - Toledo, Ohio Malinta, Ohio - Tecumseh, Michigan | |

The TD&B was part of the much larger Toledo, Cincinnati & St. Louis Railroad which was attempting to establish a narrow-gauge trunk line across the Midwest. The ambitious plan ultimately failed and after entering receivership in August of 1883 the Ironton Railroad was sold back to its original owners the following year.

The group subsequently reincorporated the property as the Iron Railway. After a half-century of service it fell into the Detroit Southern Railroad's hands, a DT&I predecessor, on September 25, 1902. Here, it was utilized as a southern outlet by opening connections with the Norfolk & Western and Chesapeake & Ohio.

Springfield, Jackson & Pomeroy Railroad

The immediate ancestry of the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton begins with another narrow-gauge, the Springfield, Jackson & Pomeroy Railroad (SJ&P) incorporated on December 14, 1874.

The southwestern region of Ohio, particularly Jackson County, was known for its rich coal reserves in the latter 19th century and several railroads were established here to tap the resource.

As Dr. George Hilton notes in his book, "American Narrow Gauge Railroads," the SJ&P was the third-longest such operation in the country when completed on July 18, 1878.

Logo

It maintained a pair of disconnected segments; one ran from Springfield to Luray while the other linked Washington Court House with Jackson. To join the two, five miles of trackage rights were utilized over another narrow-gauge, the Dayton & Southeastern Railroad. In total, the railroad ran 108 miles.

The SJ&P was ultimately successful in reaching the coal fields its promoters had long sought. However, with only short hauls available, rail movements were not particularly profitable and it struggled right from the start. This problem would plague the railroad until its acquisition by Henry Ford.

In a scene that probably dates to the early 1950's based on the new GP7's in the background we see lots of power laying over at the DT&I's roundhouse in Flat Rock, Michigan. In the foreground is 0-8-0 #253 and 2-8-0 #414. Philip R. Hastings photo. Author's collection.

In a scene that probably dates to the early 1950's based on the new GP7's in the background we see lots of power laying over at the DT&I's roundhouse in Flat Rock, Michigan. In the foreground is 0-8-0 #253 and 2-8-0 #414. Philip R. Hastings photo. Author's collection.Another issue was its poor construction and rugged profile. An especially troublesome location was the so-called "Summit Hill" situated about halfway between Bainbridge and Waverly. Here, the route wound its way up the side of a hill with grades of over 2% and curves as sharp as 22 degrees.

During the early years it became a popular destination for excursions thanks to the area's surrounding beauty. However, it was an operational headache that persisted until its abandonment in the early 1980's. There were various plans put forth to bypass this expensive stretch of line but none were ever carried out.

The SJ&P's monetary issues began before it had even commenced regular service; built at a cost of $1.5 million the company was sued by its contractor in 1876 for unpaid construction, totaling roughly $800,000.

Springfield Southern Railroad

Unable to do so, it was placed into receivership and sold in 1879 where it was reorganized as the Springfield Southern Railroad on November 3rd. Immediately, the new owners set about converting the route to standard gauge, completing the project by January 1, 1880.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40 #405 goes for a spin on the turntable at Flat Rock, Michigan in September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40 #405 goes for a spin on the turntable at Flat Rock, Michigan in September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.Ohio Southern Railroad

The new company operated independently for only a year before its acquisition by Austin Corbin's Indiana, Bloomington & Western Railway on May 1, 1881. It was then renamed as the Ohio Southern Railroad on May 21st.

Like many individuals during that era he had an aspiring plan of stringing together a series of railroads to create a much larger network; in this case, a through route from Lake Erie at the port city of Sandusky to Cincinnati, Columbus, and Dayton. Through acquisition and new construction much of it was in place by 1882.

However, Corbin overextended his finances and fell into receivership with the railroad spun-off as an independent in 1886. Back under private ownership a new idea was hatched to build northward and reach Lima. Initial surveys commenced in 1892 and the line was finished by late 1893.

At the same time promoters attempted to push rails eastward toward Pomeroy in opening an Ohio River connection; in addition, spurs would be built eastward to Columbus and westward to Cincinnati. From the southern end-of-track at Wellston rails made it only as far as Cornelia (7 miles) by 1893.

In its quest to reach the larger cities an abandoned property was purchased with short extensions opened to Sedalia and Kingman that cut across the north-south main line at Jeffersonville. Unfortunately, the entire scheme was poorly planned and no further construction ever took place.

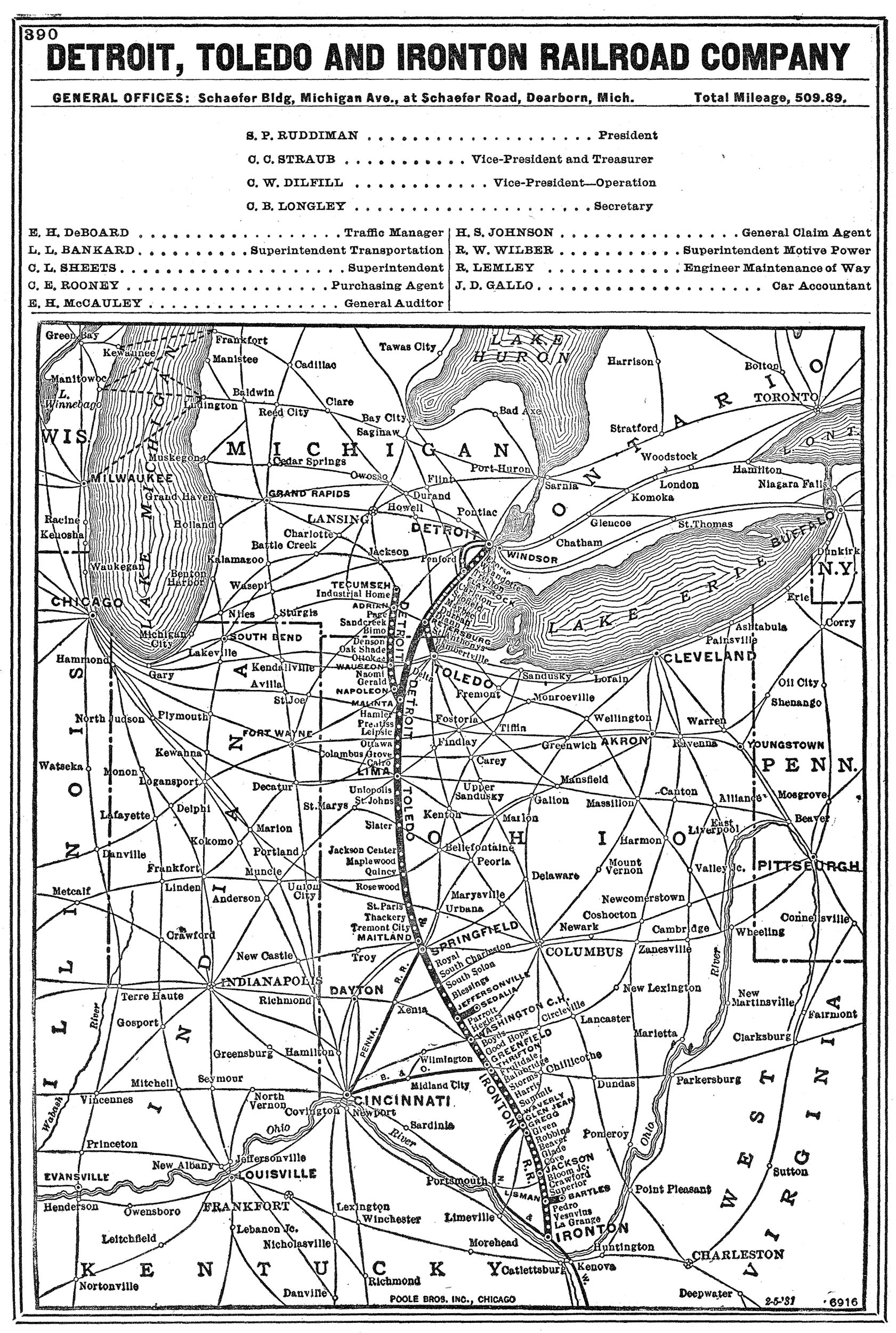

System Map (1940)

Detroit Southern Railroad

By decade's end the Ohio Southern (OS) was out of money and out of options. In bankruptcy once more it was purchased by Fred Lisman in 1901, consolidating it with the Detroit & Lima Northern (D&LN) to form the Detroit Southern Railroad on June 1st.

The D&LN carried its own interesting history; it began as the Lima Northern Railway in 1895, opening from Lima to the Michigan state line on August 1, 1896. A year later it became the D&LN and by 1901, just before it was sold, managed to piece together a connection into Detroit.

Its own bankruptcy allowed Mr. Lisman to purchase the property within weeks of acquiring the failed OS. Soon after creating the Detroit Southern, Lisman added the aforementioned Iron Railway on September 25, 1902. The small road was physically disconnected from the rest of the network.

To join the two, an 18 mile segment was completed in 1903 although still required trackage rights over the Baltimore & Ohio from Jackson to a location known as Bloom Junction (where the new connection commenced) to enjoy through service. After these rights were secured, a unified, north-south routing spanned western Ohio for the first time.

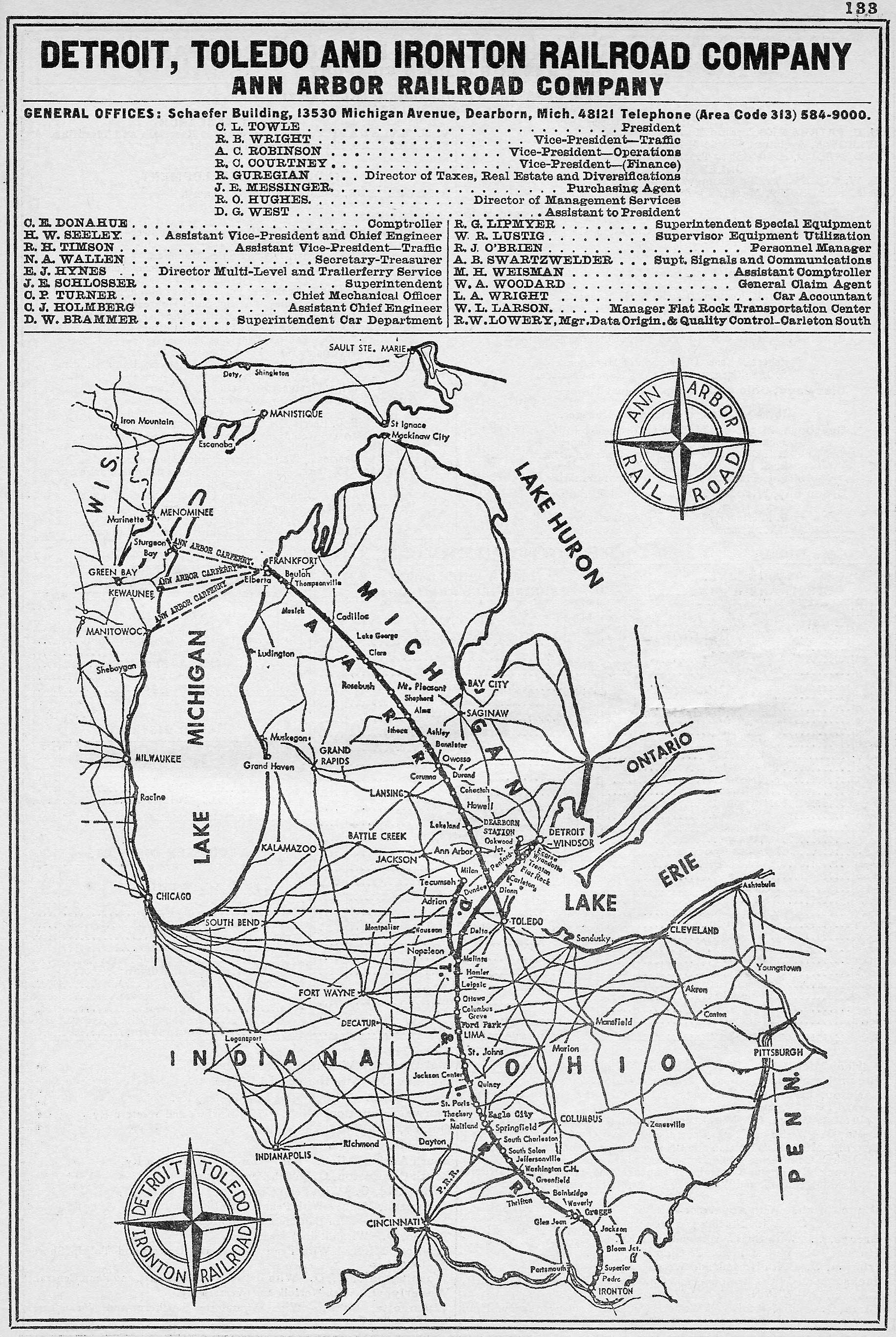

System Map (1969)

Expansion

As the Detroit Southern was attempting to secure dock facilities along Lake Erie for coal and iron ore yet another receivership occurred on July 6, 1903. Scott Trostel's book, "The Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad: Henry Ford's Railroad," notes that two years later Harry B. Hollins & Company purchased the assets on May 1, 1905 forming the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railway.

The new name obviously portrayed the owners' hope of finally establishing direct service into Toledo. In the meantime a much needed infrastructure improvement program was launched involving the laying of heavier rail and additional ballast.

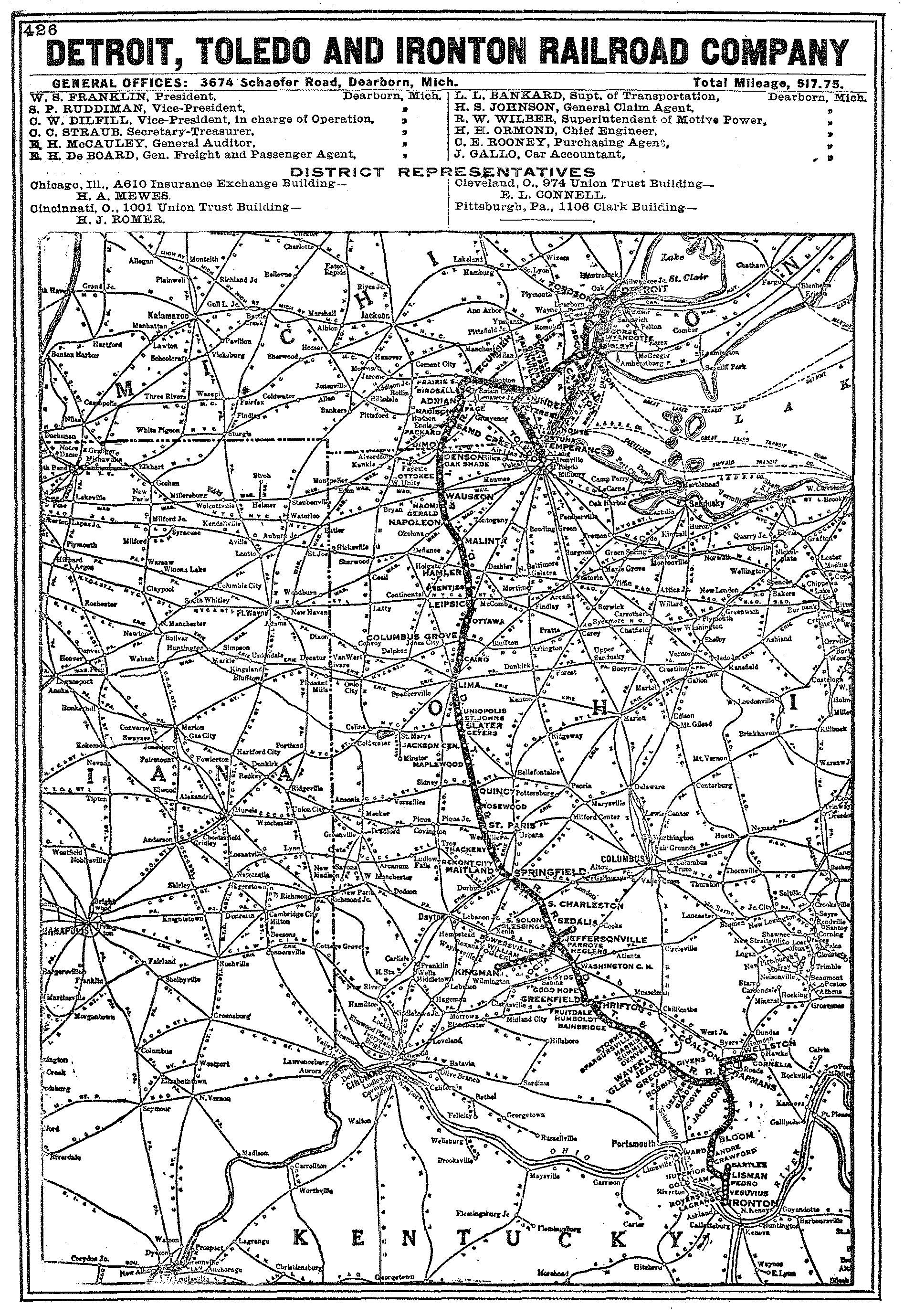

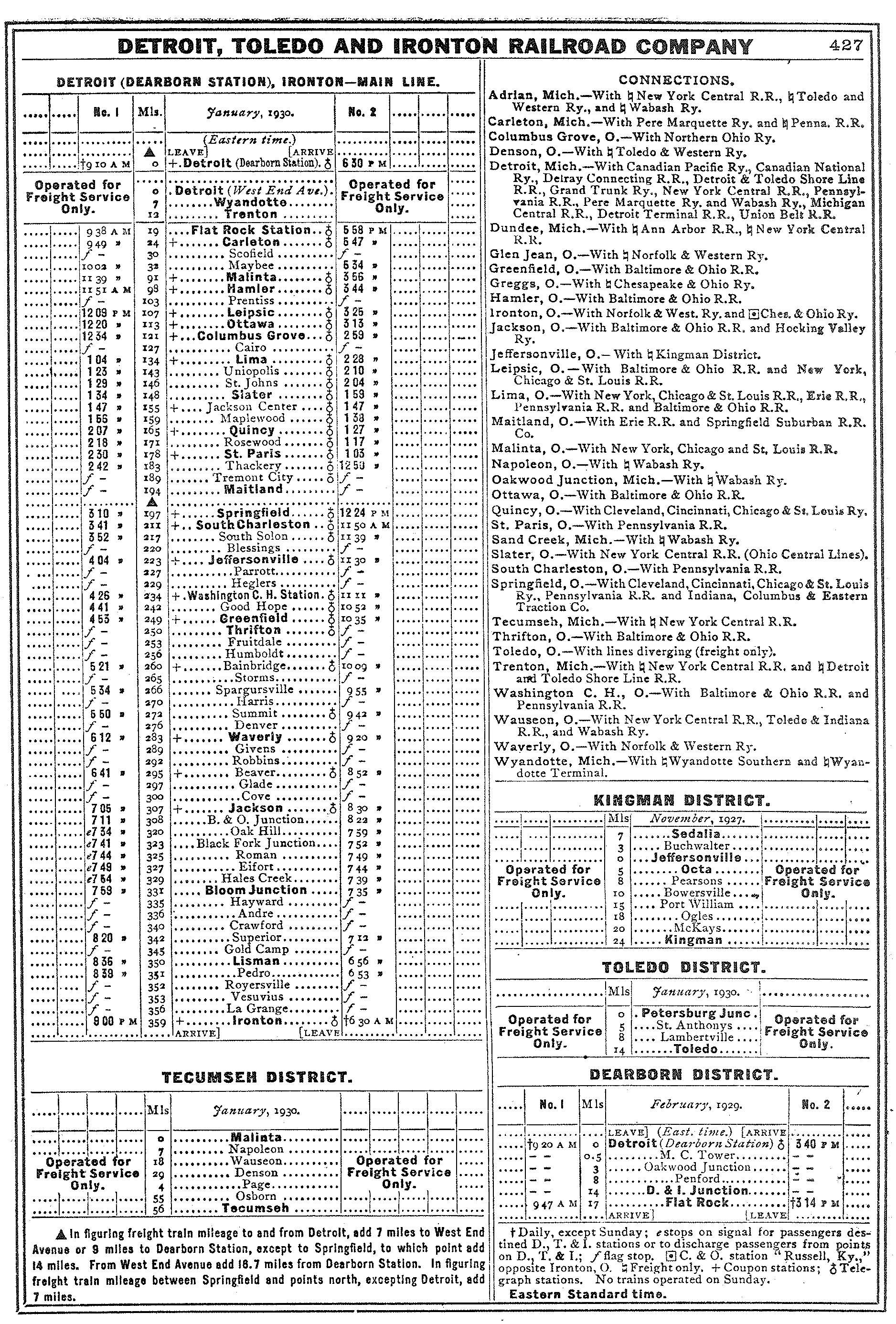

Timetables (1930)

While this particular problem was addressed from time to time it remained an issue beyond the Henry Ford era. Aside from trackage enhancements and centralizing maintenance work at Jackson, Ohio, the Hollins ownership accomplished little.

A project to extend beyond Ironton and into the coalfields of Kentucky was unsuccessful as was an attempt to build a new main line towards Detroit in an effort to avoid Lake Shore & Michigan Southern trackage rights.

The latter involved a new branch from the original route at Napoleon, Ohio to Tecumseh, Michigan, completed in 1907. The entire idea proved fruitless and within a year was abandoned but what became the Tecumseh Branch endured for several years to serve the agricultural business.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40-2's #421 and #419, along with GP38AC #210, have arrived at the Penn Central yard in Sharonville, Ohio with a southbound freight on the evening of June 19, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP40-2's #421 and #419, along with GP38AC #210, have arrived at the Penn Central yard in Sharonville, Ohio with a southbound freight on the evening of June 19, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.Henry Ford's Railroad

The Hollins ownership lasted but a few years when receivership occurred once more on February 1, 1908. This time the company was reorganized as the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad on March 1, 1914. Two significant developments occurred at this time; first, the company unveiled its famous "DT&I" circular herald, and second was a direct route into Toledo.

The 22-mile extension ran southeastward from the main line at Petersburg, Michigan and acquired via lease of the small Toledo-Detroit Railroad on May 1, 1916. The DT&I had only just begun enjoying better years when the United States was dragged into World War I.

The railroad, like the rest of the industry, was placed under federal control through the United States Railroad Administration on January 1, 1918. It was returned to private ownership in 1920 completely rundown and worn out.

It limped along until legendary automaker, Henry Ford, recognized its potential in serving his gigantic new River Rouge Complex under construction in Dearborn, Michigan. He purchased the property on July 9, 1920 and immediately set about an infrastructure improvement program.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton caboose #125 at the railroad's large yard in Flat Rock, Michigan; September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton caboose #125 at the railroad's large yard in Flat Rock, Michigan; September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.The first task was opening a direct rail connection to his River Rouge facility via a 16-mile extension which reconnected with the DT&I main line at Flat Rock. There was also a new shops built at River Rouge, the Fordson Shops, which took over as the railroad's primary facility for overhauling, rebuilding, and repairing locomotives.

With deep pockets, Ford instituted an array of new policies, all aimed at improving morale and turning the DT&I into a first-class, profitable operation. This was most conspicuous in the equipment where the locomotives became immaculate machines, heralding back to the early days when motive power was treated as works of art.

There was nickel plating applied to all piping and fixtures, boilers polished to a high shine, and wheels receiving white-wall treatment. The fleet was so impressive it caught the attention of other railroads. In just a few years the DT&I had went from a relatively forgotten regional to the envy of the industry.

Unquestionably, Ford's railroad involvement is best remembered for his ambitious electrification project. He was a big proponent of this motive power, recognizing its cost-savings potential and cleanliness, both hallmarks of his business mantra.

Electrification

His ultimate goal involved an incredibly audacious three-staged plan; electrifying the entirety of the DT&I, opening an extension to Deepwater, West Virginia where an interchange would be established with the lucrative Virginian Railway, and purchase this coal-hauler to create a through route to tidewater at Newport News/Norfolk, Virginia.

According to William Middleton's article, "Henry Ford And His Electric Locomotive" from the September, 1976 issue of Trains Magazine, he planned to first electrify the northernmost 16 miles from River Rouge/Dearborn to Flat Rock.

Construction on the new double-tracked line began in 1923 and opened on January 4, 1926, following completion of the electrification and two locomotives. Power for the system was supplied by the River Rouge generating station and the locomotives, custom-built by Ford himself, were impressive machines.

The boxcabs (#501-A and #501-B) were designed to operate together, carrying a D-D+D-D wheel arrangement, but could also operate independently. They could produce 5,000 starting horsepower, and 3,800 horsepower while in continuous operation with a tractive effort of 225,000 pounds at 33.5% adhesion.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP35 #355 was photographed here in Dearborn, Michigan on November 21, 1964. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP35 #355 was photographed here in Dearborn, Michigan on November 21, 1964. American-Rails.com collection.The electrification was a 25-cycle, single-phase alternating current (AC) system at 22,000 volts. Perhaps just as impressive was the catenary, supported by massive, reinforced concrete arches weighing 7.5 tons each! The reasoning for such over indulgence, as Ford put it, was so the system would last indefinitely.

It turned out he was correct as several arches still stand today. The electric motors performed admirably although it appears the major issue involved the generating plant, which could support both the plant's and railroad's needs. Unfortunately, the complete electrification and Virginian merger never had a chance to materialize.

Ford certainly had the financing and vision to do so, going so far as to writing an essay about it in 1921 entitled, "If I Ran The Railroads."

His time with DT&I proved short-lived. He became increasingly fed up with the regulated and bureaucratic nature of the railroad business, which oversaw everything from mergers to rate changes through the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

Ford was also constantly at odds with the agency. The ICC once even fined him $20,000 for violating the Elkins Act, which forbade railroads from offering rebates to shippers, an incentive that might hurt a competitor.

After Ford and Postwar Years

After just nine years of ownership, Ford abruptly gave up railroading, selling the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton to a Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary known as PennRoad on June 27, 1929. The electrification was quickly scrapped along with the impressive locomotive fleet.

But the road remained profitable, still heavily involved in the transportation of automotive traffic. The company weathered the depression years then purchased its first diesel in 1941, SW1 #900. A decade passed before it picked up its first road-switchers in 1951, Electro-Motive's GP7.

Over the next few years steam was slowly retired until the final run took place on December 24, 1955 when 2-8-2 #805 completed its work along the northern end of the line. The decade was also a transition period in other ways when mixed train service ceased on May 8, 1954 signaling the end of passenger trains on the DT&I.

Ann Arbor Railroad

The Detroit, Toledo & Ironton had an on-and-off-again relationship with Michigan's regional Ann Arbor Railroad. The "Annie," which ran from Toledo, crossed the DT&I at Dundee, and terminated at Frankfort where car-ferry operations were carried out across Lake Michigan, was controlled by the DT&I dating back to its original formation in 1905.

The two were also involved with trackage rights agreements at various points over the years. The DT&I lost control after its 1908 bankruptcy. However, it once again found itself over the Annie in August of 1963 after essentially forced to purchase the property by Pennsylvania Railroad during its parent's merger proceedings with New York Central.

When Penn Central collapsed in 1970 the conglomerate still controlled the DT&I but since this ownership was through a subsidiary the smaller road was not caught up in the organization. Upon Conrail's startup in 1976 the two properties were permanently separated.

Final Years

When the Pennsylvania and New York Central created the disastrous Penn Central Transportation Company on February 1, 1968 the company survived barely two years before entering bankruptcy occurred on June 21, 1970.

The DT&I, still profitable, was held by the receivership until it being caught up in the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail)'s creation in 1976.

The initial plan was to abandon most of the railroad south of Delta, Ohio which was firmly rejected. It ultimately managed to remain out of Conrail altogether while gaining trackage rights into Cincinnati. As it turns out, the idea to abandon much of the railroad's southern half was not without merit.

This section had never been particularly profitable and as a result, the infrastructure was lightly maintained. In addition, by the 1970's many interchange partners had been lost through mergers and bankruptcy. By then, the DT&I was largely a linear system-only, having lost its few branch lines.

Electric Roster

| Road Numbers | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Date Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| 501A-501B | D-D+D-D | Ford | 1925 |

The boxcabs were designed in conjunction with Westinghouse, which provided the electrical components. To eliminate the need for substations, the locomotives carried this equipment on-board.

Each unit was essentially two, semi-permanently coupled locomotives (four total) carrying a 225-horsepower traction motor on each axle. Both units, combined, weighed 745,600 pounds.

They could produce 5,000 horsepower starting, and 3,800 horsepower in continuous operation while generating a starting tractive effort of 225,000 pounds at 33.5% adhesion.

They were scrapped in 1930 following two events that year: first, new owner PennRoad (PRR) did not believe the short electrified segment was cost-effective and second, the units had derailed near the River Rouge Complex, a result of human error.

Diesel Roster

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP38 | 200-206*, 210-214 | 1966-1970 | 12 |

| GP38AC | 207-209 | 1970 | 3 |

| GP38-2 | 215-227 | 1971 | 13 |

| GP38-2 | 228 (1776)** | 1975 | 1 |

| SD38 | 250-254 | 1969, 1975 | 5 |

| GP35 | 350-357 | 1964 | 8 |

| GP40AC | 400-405*** | 1968 | 6 |

| GP40-2 | 406-413 | 1972 | 8 |

| GP40-2 | 414-421*** | 1973 | 8 |

| GP40-2 | 422-425 | 1979 | 4 |

| SW1 | 900-901 | 1941 | 2 |

| NW2 | 910-916 | 1948 | 7 |

| SW7 | 920-924 | 1950 | 5 |

| GP7 | 950-973 | 1951-1953 | 24 |

| GP9 | 980-992 | 1955-1957 | 13 |

* GP38's #200-204 were originally ordered by Maine Central but sold to DT&I. They spent their early years operating on the Ann Arbor.

** This unit wore a striking red, white and blue livery to celebrate America's Bicentennial in 1976.

*** Leased by the DT&I.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP35 #354, in Grand Trunk Western colors, at Flat Rock, Michigan; September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

Detroit, Toledo & Ironton GP35 #354, in Grand Trunk Western colors, at Flat Rock, Michigan; September, 1982. American-Rails.com collection.The only remaining spur still in service was the Tecumseh Branch, which saw its last train in 1980 (after 1965 the DT&I abandoned its Toledo Branch in favor of the Ann Arbor's alignment; to continue reaching that town after Conrail's startup required trackage rights once more).

The Penn Central's estate's Pennsylvania Company (Pennco) sold the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton to Grand Trunk Western in 1978 following ICC approval.

The formal takeover occurred on August 1, 1980. The DT&I slowly disappeared after this date as its southern network was abandoned in stretches south of Washington Court House from 1981 through early 1984.

The corporate existence of the DT&I disappears at this time when it was merged into the Grand Trunk Western on January 1, 1984. Ironically, GTW ownership lasted less than ten years. In 1990 it sold off the Springfield to Washington Court House section to new short line operator, Indiana & Ohio.

Later that decade, in 1997, much of the remainder was also purchased by the I&O as far north as Flat Rock, Michigan. Today, the I&O, a longtime division of RailAmerica, is part of the Genesee & Wyoming family (2012). The railroad states its traffic base includes, "ethanol, farm products, fertilizers, lumber, paper, and steel."

Recent Articles

-

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad. -

Delaware Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:23 PM

Delaware may rank 49th in state size but has a long history with trains. Today, a few museums dot the region. -

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here.