Chicago Union Station: Photos, History, Current Use

Last revised: September 10, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Chicago Union Station today stands as one of the last reminders of the city’s storied history with passenger trains.

It once boasted no fewer than a half-dozen terminals served by all of the major railroads reaching there with legendary trains such as the Broadway Limited, Super Chief, and 20th Century Limited all boarding at different locations.

While the station’s passenger concourse was torn down in the late 1960s the main waiting room and the rest of the facility continues to be used in its original capacity by Amtrak and local Metra services.

The station’s future also appears quite secure. As Amtrak's third busiest terminal (according to historian John Gruber), Chicago Union bares witness to tens of thousands of travelers and commuters every day.

History

No other major U.S. city was served by so many passenger terminals as Chicago. Long regarded as the country's rail hub nearly all of the major eastern, western, and southern trunk lines met in the Windy City to exchange freight and passengers.

Interestingly, no centralized union station was ever conceived although groups of carriers allied together and eventually built six different facilities including:

- Dearborn Station

- Central Station (Illinois Central)

- LaSalle Street Station

- Grand Central Station

- Northwestern Station (Chicago & North Western)

- Chicago Union Station (CUS)

The latter terminal had two predecessors before the current building was completed. According to Brian Solomon's book, Railroad Stations, the first was opend in 1858 but alas destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire in 1871.

Other Chicago Terminals

Chicago served so many railroads that even if every major system had agreed upon one, massive centralized union station it likely would never have been feasible. As it were, six prominent facilities sprang up around the city.

Along with Chicago Union Station these included Dearborn Station, Grand Central Station, North Western Terminal, Central Station, and LaSalle Street Station.

Interestingly, while Union Station often earns the most recognition, Dearborn actually witnessed more usage with several major railroads calling there.

Alas, today all of these magnificent facilities are mere shadows of their former selves, altered in some manner through either demolition (partial or complete) or adaptive reuse.

North Western Terminal

Sometimes referred to as North Western Station this facility was Chicago & North Western's primary terminal in the Windy City until the railroad finally discontinued all passenger and commuter services during the 1970s.

Designed by architects Frost & Granger (Charles Sumner Frost and Alfred Hoyt Granger) in the Renaissance Revival style it opened for service in 1911 and replaced Wells Street Station.

The new facility was located at Madison and Canal Streets featuring five beautiful Corinthian columns on the main façade flanked by decorative clocks above them.

Inside was the building's main concourse along with dressing rooms, baths, and a doctor's office. The main waiting room was roughly 200 feet long featuring an 84-foot, barrel-vaulted ceiling.

To help improve traffic flow North Western Terminal featured dual concourses; the upper-level hosted long-distance passenger trains while a street-level facility was tailored for commuters.

Overall, the station was served by 16 staging tracks covered by an 894-foot long train shed. The three story building had cost $20 million and remained largely unchanged until 1984 when the headhouse was razed to construct the 42-story Citicorp Center. Today, the location is known as the Ogilvie Transportation Center and still served by Metra.

LaSalle Street Station

This facility, located along LaSalle and Van Buren Streets, was opened on July 1, 1903 and built by the same architects as North Western Terminal, Frost & Granger.

Two previous facilities had occupied the site before the current building was erected. LaSalle was certainly the least impressive from an architectural standpoint, essentially a 12-story, steel-frame office building with platforms and tracks.

From its earliest days a New York Central predecessor utilized the station (Lake Shore & Michigan Southern) and was later joined by the Rock Island.

These two roads were always the primary tenants although for a brief period, from 1904 until 1913, the small Chicago & Eastern Illinois also used LaSalle.

Following the Penn Central merger the carrier integrated its services into nearby Union Station after October 26, 1968. The Rock Island continued using the facility into the 1970s and today Metra still operates commuter trains at the location.

Dearborn Station

The oldest of Chicago's great terminals, Dearborn opened on May 8, 1885 designed in the Romanesque Revival style by architect Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz.

The pink granite structure, located at the corner of what is today West Polk Street and South Plymouth Court, was only three stories tall but featured a magnificent center clock tower standing nearly 200 feet over the surrounding landscape.

In addition, a 700-foot train shed extended behind the head house. The depot had cost nearly $500,000 and had to be rebuilt in the mid-1920s following a severe fire that damaged the tower.

The Santa Fe was the most notable to occupy Dearborn while other major carriers to use it included the Chesapeake & Ohio, Chicago & Eastern Illinois, Chicago & Eastern Illinois, Monon, Erie (later Erie Lackawanna), Grand Trunk Western, and Wabash. During its peak years a total of 25 railroads served the station.

When Amtrak took over intercity services on May 1, 1971 Dearborn was shuttered in favor of Union Station. Today, its head house remains but all approach and staging tracks have been removed with the property redeveloped.

Central Station

This facility was Illinois Central's primary Chicago terminal, located at the south end of Grant Park near Roosevelt Road and Michigan Avenue.

It opened on April 17, 1893, replacing an aging depot, designed by architect Bradford Gilbert in the Romanesque Revival style.

The station featured nine stories used as the railroad's general offices while a gorgeous thirteen-story, 225-foot clock tower adorned one corner.

In addition, there was a magnificent three-story waiting room constructed of marble with an outdoor balcony overlooking Lake Michigan (at the time the station and tracks lay right next to the waterfront).

With a steep, pitched roof and spiral peaks surrounding its tower the building carried a very Medieval look. Central Station served IC's long-distance trains and local commuter services.

The final train to use the terminal was the southbound Panama Limited, departing on April 30, 1971. A few years later the entire complex was demolished.

Grand Central Station

The Baltimore & Ohio's primary Chicago terminal was Grand Central Station located along Harrison Street on the city's Southside.

This facility had originally opened in 1890, funded by the Chicago & Northern Pacific, then a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific. Architect Solon S. Beman was chosen for the project, conceiving a terminal in the Norman Castellated style with a marvelous 247-foot clock tower.

In addition was an enormous train shed spanning 555 feet in length, 156 feet wide, and 78 feet high. During the financial Panic of 1893 Northern Pacific lost control of the property and it was sold at foreclosure to the B&O in 1910.

Other tenants to use the building included the Chicago Great Western, Pere Marquette, and Soo Line while the C&O later dispatched its trains to the station.

The B&O still owned Grand Central when it elected to raze the structure to sell what it perceived was valuable property beneath. Unfortunately, the ground never sold and largely remains unoccupied today.

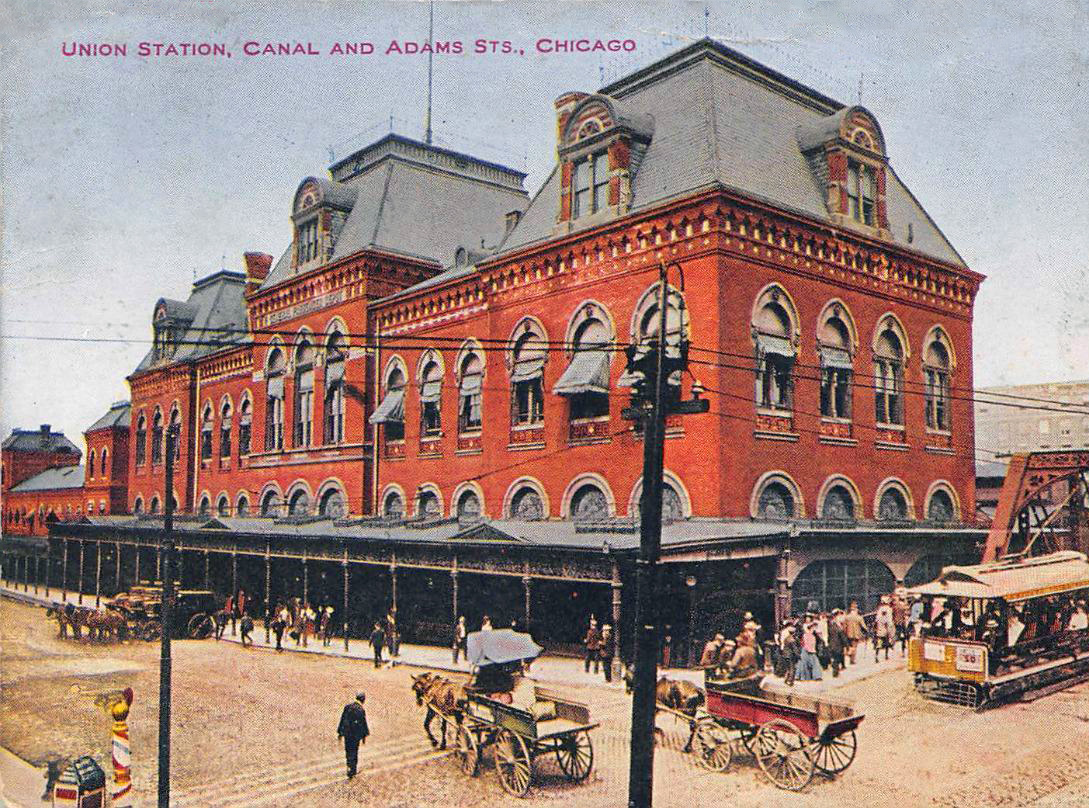

A second terminal was then finished in 1880 by Pennsylvania Railroad's Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago and used by:

- Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (later Milwaukee Road)

- Chicago & Alton (predecessor to the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio)

- Chicago, Burlington & Quincy (Burlington)

Constructed in the Victorian Style and largely laid in brick it was a beautiful facility featuring arched windows and doorways trimmed in stone.

As traveling demands soared after 1900 the consortium formed the Chicago Union Station Company to operate and oversee the construction of a new station in 1913.

As Mr. Solomon notes in his book, Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals, the PRR owned a 50% stake in the corporation while the Milwaukee and Burlington each owned 25% (the C&A was merely a tenant).

Initially, the new terminal was meant to include the Michigan Central (New York Central) while the Chicago & North Western also contemplated joining. However, in the end neither of these two railroads joined the group.

A pair of Pennsylvania E8A's navigate the web of trackage at Chicago Union Station during the early 1960's. Author's collection.

A pair of Pennsylvania E8A's navigate the web of trackage at Chicago Union Station during the early 1960's. Author's collection.Construction commenced in 1914 but World War I delayed completion by several years and the third (current) Union Station did not open until 1925.

The original designer was architect Daniel Burnham, well known for his work on Washington Union Station, who envisioned the Chicago facility in the classic Beaux-Arts style (one of the last ever built employing this architectural design).

The building featured Indiana limestone and Tuscan columns, similar to that of the late Pennsylvania Station in New York City.

Unfortunately, Burnham died before its completion and the firm Graham, Anderson, Probst & White was hired to finish the project.

Chicago Union Station’s original layout was roughly a “back-to-back” setup with only the Milwaukee Road using the north end served by ten tracks while the Pennsylvania, Burlington, and GM&O used the southern end featuring fourteen tracks. In addition, there were two through tracks connecting both ends.

Burlington Northern E9AM #9925 has a two-car commuter train at Chicago Union Station in August, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.

Burlington Northern E9AM #9925 has a two-car commuter train at Chicago Union Station in August, 1974. American-Rails.com collection.The station was also designed as two distinct sections, the main waiting room and passenger concourse were separated but worked as one with the two connected via an underground passageway.

The concourse was destroyed in 1969 to make way for a new office building but the main waiting room still stands today.

Known as The Great Hall, the room measures over 34 meters in height to a magnificent vaulted skylight and the wooden benches in the room are arranged for visitors to easily wait for their connections.

The hall was the building's hallmark feature and is where the photo below was taken. Aside from the splendor of the The Great Hall, Union Station also has Tennessee marble and terracotta walls incorporated into it.

Also of note was the station's famous Fred Harvey restaurant and shops designed by architect Mary Colter.

She was often employed by the Santa Fe to construct Harvey House hotels and other facilities for the railroad along its main line across the Southwest, which came to be known as the "Santa Fe Style" of architecture.

Interestingly, the Santa Fe never used the terminal and instead dispatched from nearby Dearborn Station. While CUS was only in use during the very late years of the industry's "Golden Age" of rail travel it witnessed the flurry of World War II, one of the busiest times in its history.

At that time the station played host to more than 300 trains and 100,000 passengers every day.

Some of the best remembered streamliners called there such as Milwaukee Road's blazing fast Morning and Afternoon Hiawathas, Pennsylvania's elegant Broadway Limited, and Burlington's sharp Twin Cities Zephyr.

Today, there are no more streamliners to enjoy. However, the station remains an important facility hosting 300 trains and 120,000 travelers every weekday between Amtrak and Metra.

Chicago Union Station is the last remaining of the city's grand terminals still functioning in its original capacity. This was largely due to the startup of Amtrak, which took over most intercity passenger trains across the country during the spring of 1971.

To centralize operations in Chicago it combined all services there. After carrying out this plan the other terminals were either razed or redeveloped.

In 1984 Amtrak acquired full ownership of the facility and completed a major renovation in 1992. In June of 2015 the carrier announced another extensive update to the building that included restoring worn out staircases (using marble from the original quarry near Rome, Italy), opening previously closed areas, and restoring the former women's lounge (now known as the Burlington Room).

During 2018-2019 another restoration focused on the Great Room; the $22 million project involved restoring trim work and rebuilding the skylight which improved natural light by 50-60%.

As Mr. Gruber notes, Union Station has not received the historical coverage of other large terminals around the country but the fact that it still stands and is a Chicago Landmark is a wonderful thing indeed.

Recent Articles

-

Maryland Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 01:36 PM

The state of Maryland is where it all began with the Baltimore & Ohio. Along with the B&O Railroad Museum, several other similar organizations can be found in the state. -

Maine Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 12:58 PM

Maine's railroads have long been associated with logging and agriculture. Today, a number of museums honoring this heritage can be found throughout the state. -

Kentucky Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 20, 25 03:17 PM

Kentucky has long contained a mix of important through main lines and rich bituminous coal seams for the railroad industry. Today, a handful of museums can be found across the state.