Clinchfield Railroad: Conquering The Southern Appalachians

Last revised: August 23, 2024

By: Adam Burns

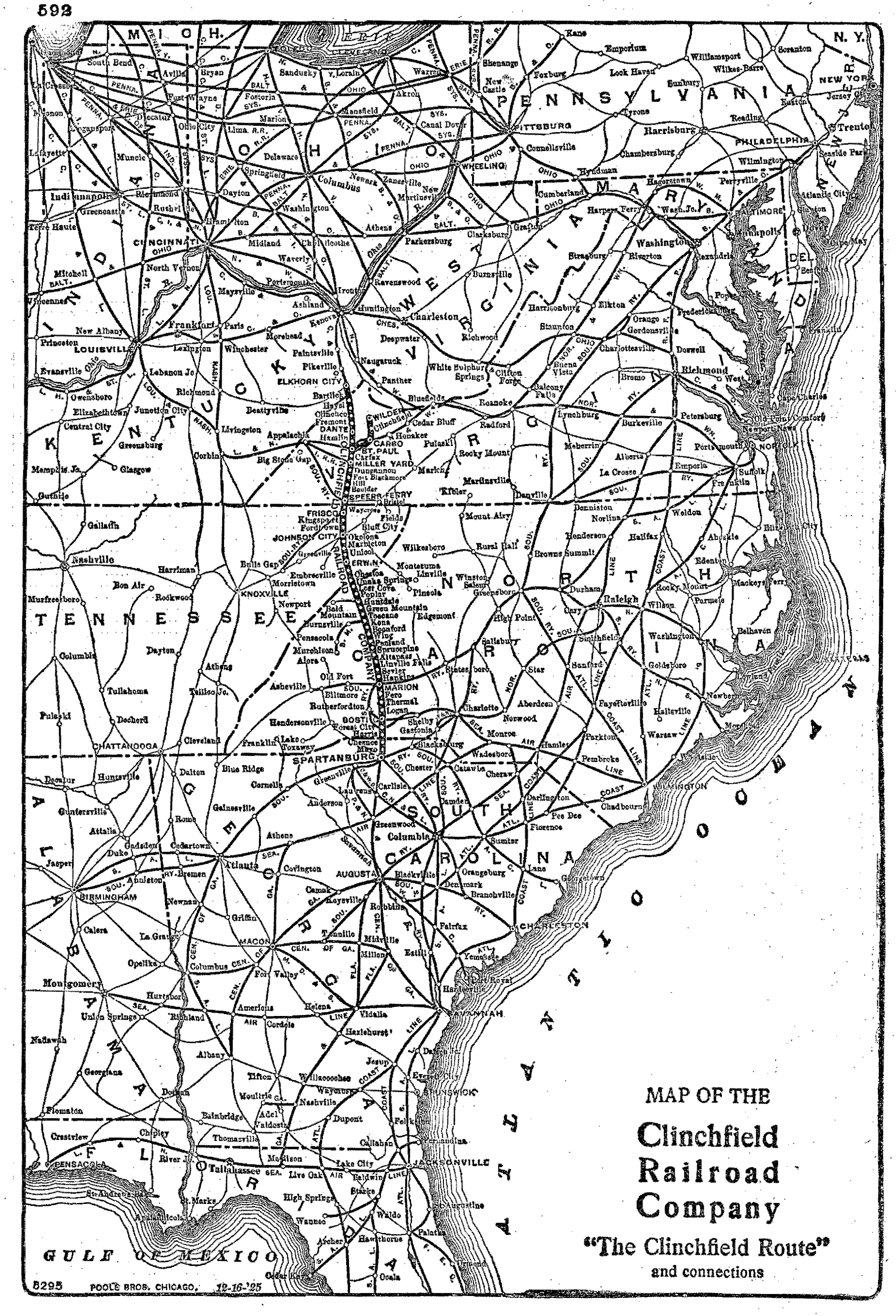

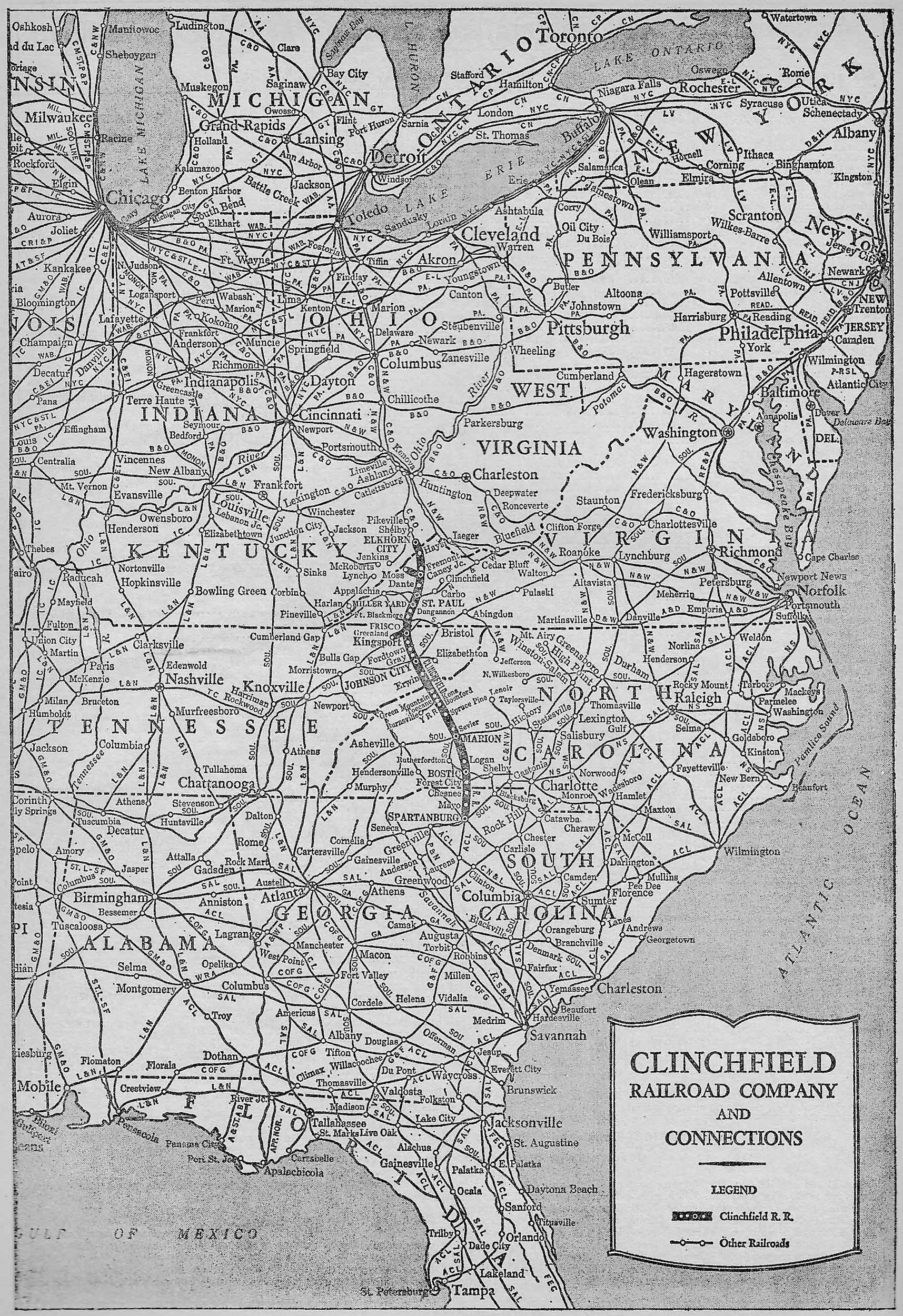

The Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio Railroad was a small but enormously profitable system tied to coal. Its network clipped the corners of five southern states running the spine of the Appalachians between Kentucky and South Carolina.

The CC&O's heritage began as an attempt to build a tidewater route linking the Ohio River with the East Coast although what ultimately became the Clinchfield carried a main line of just 277 miles.

The CRR's earliest history dated to the early 1800s while its modern network was constructed a century later.

It was so well built it operated largely unchanged as a through route into the CSX era. During the 1920s the CC&O was acquired by the Louisville & Nashville and Atlantic Coast Line, controlled through the holding company Clinchfield Railroad (reporting marks, CRR).

It remained mostly independent until the 1970s, and then went on to from the Seaboard System. With coal's decline during the 2010s, in 2015 successor CSX Transportation announced the former Clinchfield territory would play a much less important role as parts were shuttered for through service.

Then, less than two years later following a managerial change, the carrier reversed this decision with trains returning in July of 2017.

Photos

A grimy Clinchfield F3A sits outside the locomotive shops in Erwin, Tennessee. Warren Calloway photo.

A grimy Clinchfield F3A sits outside the locomotive shops in Erwin, Tennessee. Warren Calloway photo.History

The Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio's corporate history is not particularly interesting in the sense there were few major twists or turns.

It was a rather straight-forward affair involving ambitious plans which eventually settled into a more subdued role as a regional bridge route and coal hauler.

The development of CC&O's modern system, however, was a masterful display of engineering and the daily operations of machine against the mountain. It was a true sight to behold during the steam era.

The railroad's earliest ancestry can be traced back to the Cincinnati & Charleston Rail Road Company chartered in 1835 to link Charleston, South Carolina with the Ohio River according to Mike Schafer's book, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III."

In 1837 the name was changed to the Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston Railroad but despite its promoters' grand schemes only a short section was ever completed in South Carolina.

The next important development occurred in 1886 when General John Wilder, a former Union commander, chartered the Charleston, Cincinnati & Chicago Railroad.

It was better known as the "Triple C" and envisioned to run from Ironton, Ohio to Charleston, South Carolina via the "Queen City" of Cincinnati.

At A Glance

Elkhorn City, Kentucky - Dante, Virginia - Erwin, Tennessee - Marion, North Carolina - Spartanburg, South Carolina Carney Junction - Moss, Virginia St. Paul - Wilder, Virginia | |

Steam: 13 Diesel: 59 | |

Freight Cars: 7,085 Passenger Cars: 8 | |

The entire idea, even at this date, was to develop the coalfields of western Virginia and eastern Kentucky, opening arteries for black diamonds to the Midwest and Atlantic coast.

The CC&C was able to complete some construction north and south of Rutherfordton, North Carolina but the financial Panic of 1893 brought the entire enterprise to a halt.

After entering bankruptcy the assets were acquired by Boston financier Charles Hellier who organized the Ohio River & Charleston Railway in 1894.

Expansion

The OR&C had plans similar to those of the CC&C; connect the coalfields of southern Appalachia with northern and southern outlets. While Hellier did not create the modern Clinchfield he did lay down much of its original network.

By the late 19th century his OR&C had constructed, opened, or graded some 338 miles including sections between Marion, North Carolina and Camden, South Carolina (171 miles); Huntdale and Johnson City, Tennessee (35 miles); Johnson City and Dante, Virginia (74 miles); and finally Whitehouse and Ashland, Kentucky (58 miles).

Alas, Hellier wound up overextending his financial resources and, coupled with a disagreement in South Carolina involving taxes, was forced to sell off the northern and southern segments.

The route south of Marion, North Carolina was sold to the South Carolina & Georgia Railway a future component of the Southern Railway. In the north, the grade from Ashland, along the Ohio River, to Whitehouse, Kentucky was purchased by the Chesapeake & Ohio.

The C&O went on to complete the line and extend it to Elkhorn City in 1905. The property greatly helped Chessie develop its coal holdings in this region and the latter city became an important interchange with the future Clinchfield.

By 1902 Hellier had lost interest in his railroad endeavor and sold the remaining central segment between Johnson City and Boonford, North Carolina to George Carter who chartered the South & Western Railway that year, recognized as Clinchfield's immediate ancestor.

This interesting moniker was purposeful to throw off competitors so they would not ascertain exactly where Carter was intending to extend his new railroad. The idea worked although he was never able to complete the line to the East Coast as hoped.

Barely recognizable beneath all of that grime, Clinchfield GP38 #2006 and cabless covered wagon are seen here at the engine terminal in Erwin, Tennessee on April 3, 1971. Warren Calloway photo.

Barely recognizable beneath all of that grime, Clinchfield GP38 #2006 and cabless covered wagon are seen here at the engine terminal in Erwin, Tennessee on April 3, 1971. Warren Calloway photo.According to Robert Helm's book, "The Clinchfield Railroad In The Coal Fields," Carter combined the S&W with three other short systems he controlled (Lick Greek & Lake Erie, Clinchfield Northern, and Elkhorn Southern) to form the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio Railway on March 31, 1908.

From Marion, the CC&O was completed to Spartanburg, South Carolina on October 29, 1909 opening a route as far north as Dante, Virginia. It passed through the rugged Blue Ridge Mountains spanning western North Carolina while the Appalachians of western Virginia and eastern Kentucky were equally arduous.

In 1905 Carter brought in M.J. Caples from the Norfolk & Western as Chief Engineer and General Manager. Upon his recommendation the route needed significant upgrading if it were to handle heavy freight tonnage efficiently. Caples remained with the company until 1911 and oversaw much of the construction south of Dante.

As Mark Hemphill's notes in his essay, "Tough Terrain & Easy Grades," from the October, 2001 issue of Trains Magazine the Dante - Spartanburg segment was built to incredibly high standards at a cost of up to $180,000 per mile.

Logo

Across the Blue Ridge grades were kept right around 1%; southbound movements averaged from 0.5% to 1.0% (compensated) with curves of just 6 degrees while northbound movements carried around 1.2%, compensated.

The line featured a myriad of tunnels, trestles, and fill to achieve this goal. Two of the more impressive engineering feats included the 1,865-foot Blue Ridge Tunnel and the famous Clinchfield Loops.

The latter begin just south of Altapass, North Carolina (Spruce Pine) and feature a series of five horseshoe curves that includes seventeen tunnels in just 11 miles!

Even more incredible, to keep grades at 1.2% the loops total 29 railroad miles when in reality they travel a distance of only 12 linear miles from north to south.

As the book, "A History of Railroading in Western North Carolina" by Cary Poole points out, during one stretch between milepost 208 to Wasburn Tunnel a train must negotiate 16.5 miles of railroad but if one could walk this in a straight line it would only be 1.9 miles.

After the Loops opened in 1909 work began on the extension above Dante to reach Elkhorn City (35 miles), connecting there with Chesapeake & Ohio's Big Sandy Division.

Once more, the CC&O was faced with a difficult challenge; the Breaks of the Big Sandy River, just south of Elkhorn City, held a chasm descending some 1,600 feet along the eastern periphery of Pine Mountain while the Sandy Ridge Mountain loomed just north of Dante.

Company engineers were able to maintain grades of 1.5% through the Breaks while a 1.8% grade was required over Sandy Ridge which included an impressive 7,854-foot tunnel.

Mr. Hemphill notes the entire 35-mile extension had cost around $140,000 per mile and a golden spike ceremony was held at Trammel, Virginia, just north of Sandy Ridge, on February 9, 1915 signaling the completion of the 276.9-mile main line between Elkhorn City and Spartanburg.

In all, Carter's railroad featured 55 tunnels (totaling nearly 10 miles in length) and 80 bridges (totaling 3.3. miles in length). According to Scientific American it was the "...costliest railroad to cross the Appalachian Blue Ridge Mountains."

The project's expense, however, paid off in the coming years; in 1951 the road reported 4.7 million tons of merchandise freight and 9 million tons in coal.

That year it boasted an operating income of $23.6 million and in 1960 held a ridiculously low operating ratio of just 55.5%. The railroad was so well built that even into the CSX era it operated more or less unchanged.

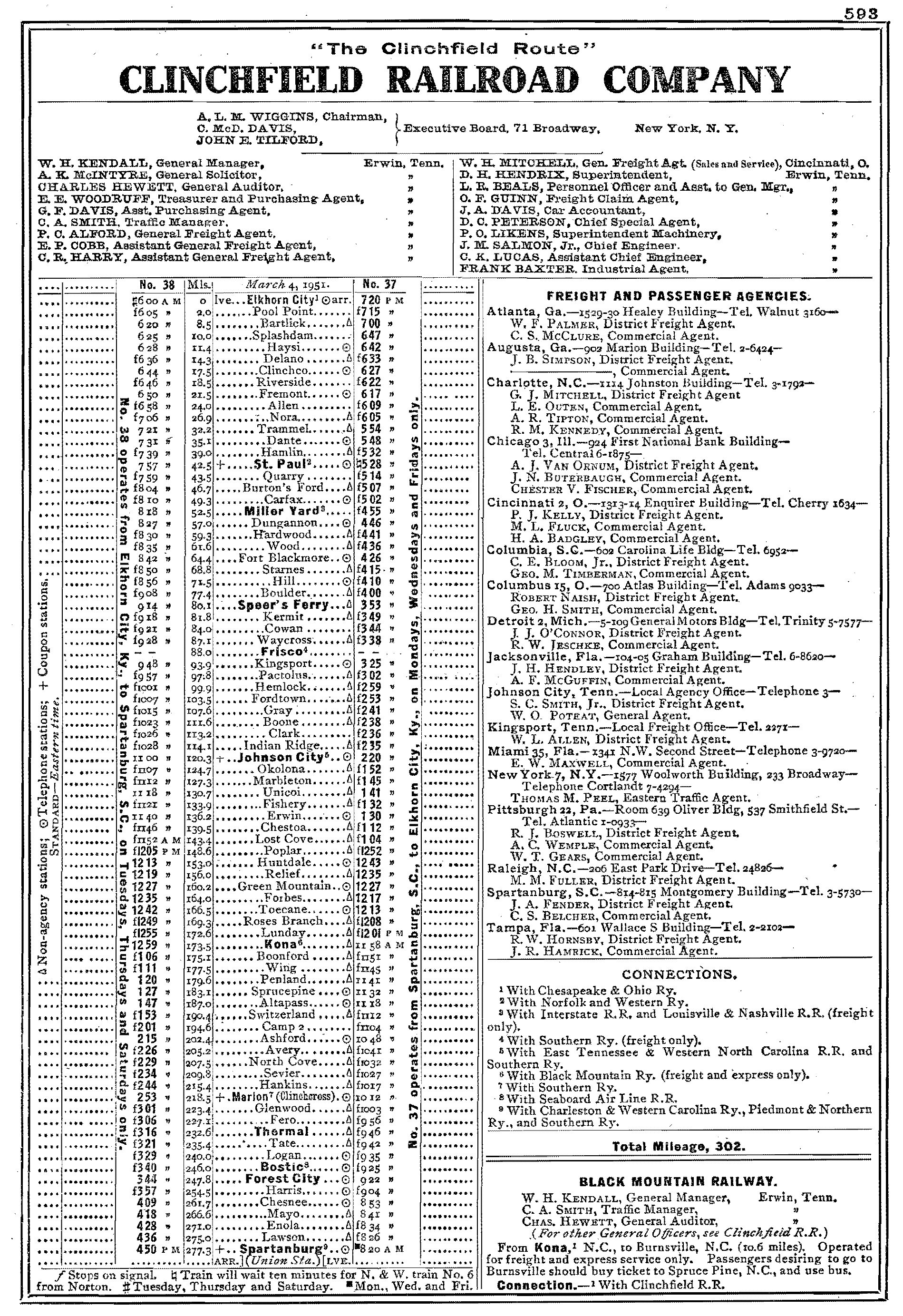

Timetables (1952)

The Clinchfield's so-called "Inside Gateway" made it ideal for bridge traffic as the numbers above attest. To the north, of course, it interchanged with the C&O for a Midwestern outlet while to the south it made important connections at Norton, Virginia with the Interstate Railroad, Louisville & Nashville, and Norfolk & Western.

All three handed traffic over to the Clinchfield, some of which moved on to Spartanburg. At this South Carolina town the railroad interchanged with the ACL, Southern, and Seaboard Air Line. Not surprisingly, its superb route drew attention from much larger carriers.

In 1924, made retroactive to May 11, 1923, the Atlantic Coast Line and Louisville & Nashville (itself controlled by the ACL), mutually agreed to lease the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio for a term of 999 years. It was placed under the holding company known as the Clinchfield Railroad and remained there for the rest of its days.

However, it continued operating largely independent, maintaining its own equipment, locomotives, and a large terminal at Erwin, Tennessee. Within this small town its locomotives were serviced and a general office was located.

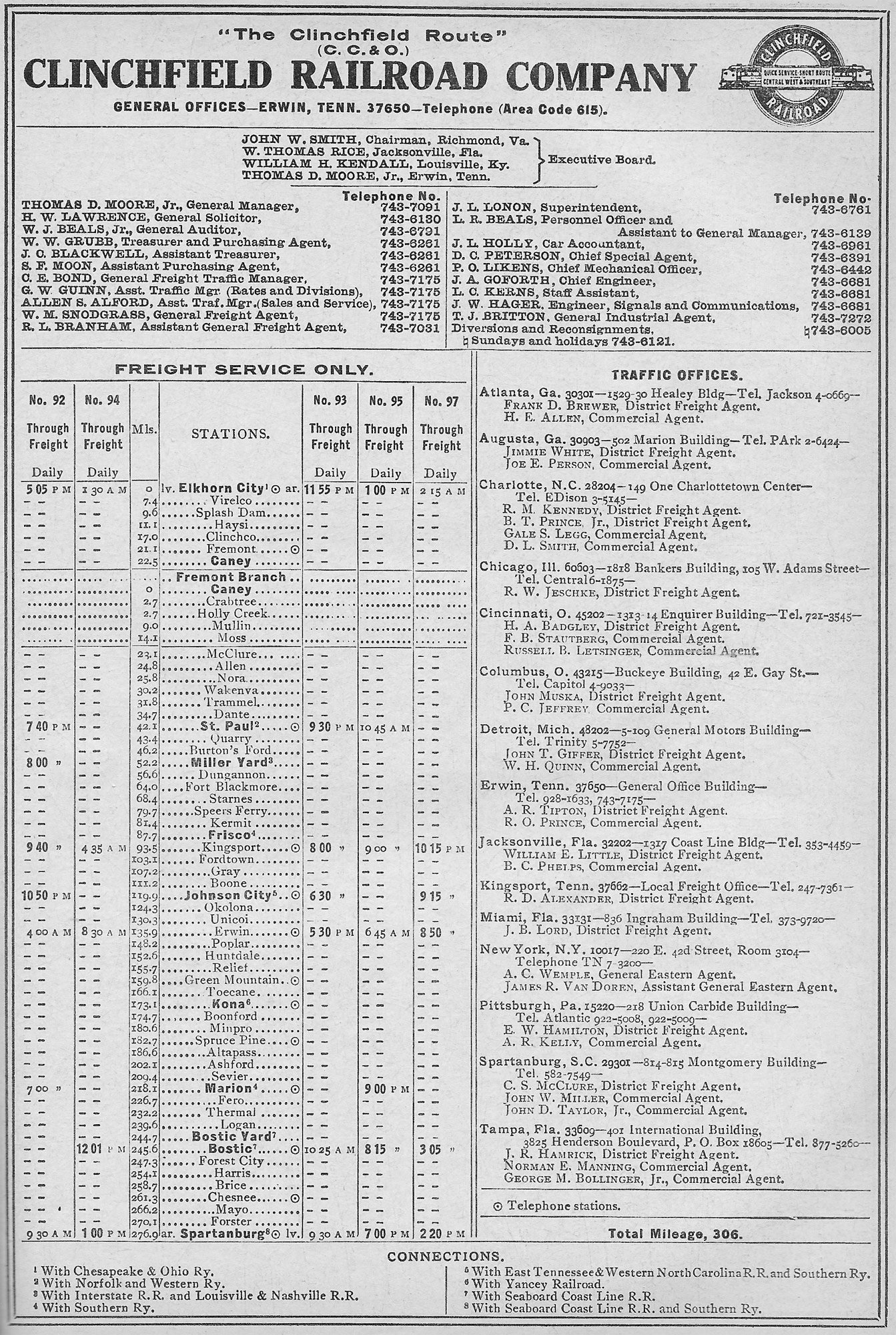

System Map (1969)

It seems coal mines dotted the Clinchfield's network everywhere. These generators of black diamonds were particularly heavy along the northern end at Haysi, Dante (The location of its major classification yard where loaded hoppers/gondolas were sorted to be shipped to their intended destination.) and Norton.

The final major extension of the Clinchfield took place with the completion of the 5.7-mile Haysi Railroad in February of 1970. What was essentially a branch served mines of the Clinchfield Coal Corporation's along Russel Prater Creek from the main line near Berta, Virginia.

Clinchfield Railroad 4-6-0 #1, the "One Spot," is dwarfed by two F7B's assisting a special passenger excursion on the Seaboard Coast Line approaching Cary, North Carolina in June, 1977. This little Ten-Wheeler now sits on display at the B&O Railroad Museum. Warren Calloway photo.

Clinchfield Railroad 4-6-0 #1, the "One Spot," is dwarfed by two F7B's assisting a special passenger excursion on the Seaboard Coast Line approaching Cary, North Carolina in June, 1977. This little Ten-Wheeler now sits on display at the B&O Railroad Museum. Warren Calloway photo.The region was so blessed with the rock that it sustained not only the Clinchfield but also the N&W, Southern, Chesapeake & Ohio, Interstate, and L&N. All six roads owed much of their success to the heavy coal tonnage originating or passing over their rails.

Coal generally moved in both directions on the CRR depending upon where it was headed; its mines generated roughly 60%, lower grade steam coal that usually found its way to power plants throughout the South. The rest, a higher grade, metallurgical coal was hauled north to steel mills located throughout the Mid-Atlantic region.

Operations

If one was around to see the Clinchfield prior to the 1950s they were treated to quite a show as huge articulated wheel arrangements like 2-8-8-2's, 4-6-6-4's, and 2-6-6-2's fought the mountain to move long strings of heavy coal over the grades.

As Mr. Schafer notes, the first steamers the CC&O utilized were four 4-6-0's, fifteen 2-8-0's, and a single 2-6-6-2 (M-1) purchased from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1909. A year later it acquired twenty more Mallet's from Baldwin; listed as Class M-2 they were numbered 510-519 and 550-559.

In 1910 it also picked up three 4-6-2's for its modest, but respectable passenger services, numbered 150-152 (P-1); it later added two more from Baldwin in 1914 numbered 153-154 (P-2).

Its first two 2-8-2's arrived in 1917, which were second-hand units (K-2 #499 arrived from the Cambria & Indiana while K-3 #498 came from the Spanish-American Iron Company).

Between 1919 and 1923 it added nineteen more, #400-408 (K-1, 1919) built by Baldwin and #410-419 (K-4) manufactured at Alco's Brooks Works.

The year 1919 witnessed the arrival of the big power which would define the Clinchfield when it purchased seventeen 2-8-8-2's from Baldwin (#700-706 and #725-734, L-1 and L-2) and another ten arrived in 1923 from Alco's Brooks Works (#735-744, L-3).

A rare Electro-Motive NW3, Clinchfield #361, is seen here in Erwin, Tennessee on March 30, 1971. This unit began its career as Great Northern #5405 in 1942. Warren Calloway photo.

A rare Electro-Motive NW3, Clinchfield #361, is seen here in Erwin, Tennessee on March 30, 1971. This unit began its career as Great Northern #5405 in 1942. Warren Calloway photo.Its final new steamers are long remembered and the most celebrated among fans; Clinchfield was one of just a few to acquire the huge 4-6-6-4 wheel arrangement. These modern machines, simple-expansion articulateds, were designed for high-speed operations.

They were based from the Delaware & Hudson's J-95's manufactured in 1940. The first eight Challengers arrived in 1943 from Alco's Schenectady plant, #650-657, and given Class E-1 while four more arrived later (#660-663, E-2).

Apparently, the railroad was so pleased they went on to pick up six more, second-hand from the Rio Grande after the World War II!

Since coal was at the heart of its business the Clinchfield did not expedite its switch from steam to diesel. A similar event unfolded on the nearby C&O and N&W, which continued maintaining their steam fleets well into the 1950s. The first diesels finally arrived in 1948 by way of F3's.

It went on to roster a fleet comprising almost entirely Electro-Motive products, except for a small collection of U36C's and a few Alco switchers.

To read much more about the Clinchfield's daily operations I would highly recommend picking up a copy of Robert Helm's, "The Clinchfield Railroad In The Coal Fields," or try to find past copies of Trains Magazine where rail historian Ron Flanary has superbly documented the road's glory days.

Clinchfield F3A #800, waving white flags, and FP7 #200 at the terminal in Erwin, Tennessee during October of 1972. The units were powering a fall foliage special that year. Warren Calloway photo.

Clinchfield F3A #800, waving white flags, and FP7 #200 at the terminal in Erwin, Tennessee during October of 1972. The units were powering a fall foliage special that year. Warren Calloway photo.Family Lines

The Clinchfield's network listed 302 route miles as of 1950, which included all main line and secondary trackage. Its previously noted branches were few as it predominantly acted as a conveyor belt for bridge and coal traffic.

The biggest change occurred in the mid-1970s when it came under the Family Lines System banner with the L&N, the new Seaboard Coast Line (a merger between the ACL and Seaboard Air Line in 1967), and a number of other smaller lines.

Timetable (1969)

With this came a new livery applied to all (with sub-lettering stenciled under locomotive cabs identifying each company) and gone was the Clinchfield’s familiar black and yellow paint scheme (Its original livery featured a gray and yellow design with black lettering. However, the heavy grime incurred regularly while passing through so many tunnels made it impossible to keep clean).

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s the Clinchfield Railroad would officially disappear when the Family Lines System formally became the Seaboard System in 1982, dissolving its corporate name. In 1986 Seaboard was merged into CSX Transportation, followed by the Chessie System a year later.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S4 | 3034, 3039, 3049 | Leased | 3 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP7 | 200 | 1952 | 1 |

| SW7 | 350-355 | 1950 | 6 |

| F3A | 800-805 | 1948 | 6 |

| F7A | 806-820 | 1951-1952 | 15 |

| F3B | 850-852 | 1949 | 3 |

| F7B | 853-863 | 1949-1952 | 11 |

| F9B | 864-868 | 1955 | 5 |

| GP7 | 900-916 | 1950-1952 | 17 |

| GP9 | 917-918 | 1956 | 2 |

| GP16 | 4600-4613 | Ex-SCL and rebuilt GP7s | 14 |

| GP38 | 2000-2009 | 1967 | 10 |

| SD40 | 3000-3008, 3015-3024 | 1966-1971 | 19 |

| SD45-2 | 3607-3624 | 1972 | 18 |

| SD45-2 | 3625-3631 | Ex-SCL | 7 |

| GP38-2 | 6000-6006, 6045 | 1978-1979 | 8 |

| SD40-2 | 8127-8129, 8131-8132 | 1980-1981 | 5 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U36C | 3600-3606 | 1971 | 7 |

Steam Roster

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| E-1, E-3 | Challenger | 4-6-6-4 |

| F-1 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| G-1, G-2 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| H-1, H-2, H-4 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| H-3 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| K-1 Through K-4 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| L-1 Through L-3 | Articulated | 2-8-8-2 |

| M-1 Through M-3 | Articulated | 2-6-6-2 |

| P-1, P-2 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

CSX Transportation

Until 2015 the former Clinchfield route served as a vital coal artery under CSX. The Class I announced on October 15th that year significant reductions would occur along the old CRR network as a result of losing more than $1 billion in coal business since 2012.

The move resulted in roughly 300 employees either losing their jobs or transferred to other areas. In addition the railroad mothballed or closed sections of the main line between Elkhorn City, Kentucky and Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Officially, the corridors affected included the Kingsport Subdivision between Shelby Yard in Pikeville, Kentucky and Erwin, Tennessee along with the Blue Ridge Subdivision between Erwin and Spartanburg.

Thankfully, this never affected the famous Santa Claus Special. It originally started during Christmas, 1943 and has operated every year since. Today it is co-sponsored by both the Kingsport Area Chamber of Commerce and CSX.

Curiously, this decision lasted fewer than two years; on March 6, 2017 E. Hunter Harrison was named Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and then formally achieved the presidency on April 19th. He has made some dramatic changes at the Class I in an attempt to implement his so-called "Precision Railroading."

As part of this endeavor, through trains were returned to the former Clinchfield during July of 2017. For how long is anyone's guess but for now this fabled stretch of railroad hums with activity once more.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Beech Creek Railroad: NYC's Pennsylvania Coal Feeder

Feb 20, 25 01:45 PM

The Beech Creek Railroad, along with the Fall Brook Coal Company line, was New York Central's penetration into central Pennsylvania's coal fields. -

Brooks Locomotive Works: 1869-1901

Feb 20, 25 01:32 PM

The Brooks Locomotive Works was notable manufacturer based in Dunkirk, New York that produced engines from 1869-1901. -

Cooke Locomotive and Machine Works

Feb 20, 25 12:58 PM

The Cooke Locomotive and Machine Works was a major manufacturer of locomotives during the 19th century. It operated from 1852-1901 before becoming part of Alco.