The "Chippewa-Hiawatha": Chicago - Ontonagon, MI

Last revised: September 8, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Milwaukee Road drew immediate acclaim and national media when it inaugurated the original Hiawatha streamliner on May 29, 1935.

Not only did the train offer virtually any on-board accommodation one could expect of a regional train but it was also blazing fast, clipping along at more than 100 mph and averaging 80 mph. The Hiawatha was uniquely Milwaukee Road and its success prompted the company to launch an entire fleet.

All were in service by 1940 and included the North Woods Hiawatha (also referred to as the Hiawatha-North Woods Service), Midwest Hiawatha, and Chippewa-Hiawatha (originally known as the Chippewa).

These secondary trains offered amenities closely aligned with the original Hiawatha flagship but their less populated corridors made them more susceptible to the automobile. As a result, all had either been canceled or lost their name by 1960.

When streamliner frenzy took hold in early 1934, introduced to the nation through Union Pacific's M-10000 and Burlington Zephyr 9900 passenger rail travel was forever changed.

After both roads successfully demonstrated not only the trains' capabilities but also their draw on the public (after all, who had ever seen a colorful, speeding steel tube before?) others soon scrambled to put their own versions in service.

The Milwaukee Road was slow to do so, lagging behind rivals Chicago & North Western and Burlington, but when the Hiawatha went on display during the spring of 1935 it was something to behold.

Photos

Milwaukee Road 4-6-2 #151 (F-1) is seen here with the "Chippewa" just off the train shed at the Everett Street Station in Milwaukee, Wisconsin circa 1950.

Milwaukee Road 4-6-2 #151 (F-1) is seen here with the "Chippewa" just off the train shed at the Everett Street Station in Milwaukee, Wisconsin circa 1950.History

The train's styling was done by industrial designer Otto Kuhler from the speedy 4-4-2 Atlantics to the "Beaver Tail" parlor-observation. Its livery was an intricate and classy mix of maroon, grey, and orange with a winged-shield draped across the locomotive's nose.

Not surprisingly, the Hiawatha's quick schedule and exquisite accommodations saw it regularly sell out, averaging 758 daily passengers through March of 1937. Net earnings were also strong, coming in at $2.49 per mile once operating costs were subtracted according to Brian Solomon and John Gruber's book, "The Milwaukee Road's Hiawathas."

Its very name evoked speed, named after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "swift-of-foot" Native American chief, "Hiawatha."

Those credited with the idea include Milwaukee Road employees Clarence E. Trophy (mechanical engineer's office), Henry T Hooker (engineer), J.B. Ennis (American Locomotive Company vice president), E.O. Reeder (former assistant chief engineer), Kenneth D. Alleman (clerk), and Charles H. Bity (chief mechanical officer, for many years he remained anonymous).

At A Glance

10 Hours, 15 Minutes (Northbound) 11 Hours, 15 Minutes (Southbound) |

|

21 (Northbound) 14 (Southbound) | |

Brass Street Depot (Ontonagon) Union Station (Chicago) |

Realizing it was sitting on a gold mine the Milwaukee Road wasted little time adding other Hiawathas to its fleet, as soon as the equipment could be put into service (this was originally in the form of hand-me-downs as new cars were built or acquired for the Hiawatha).

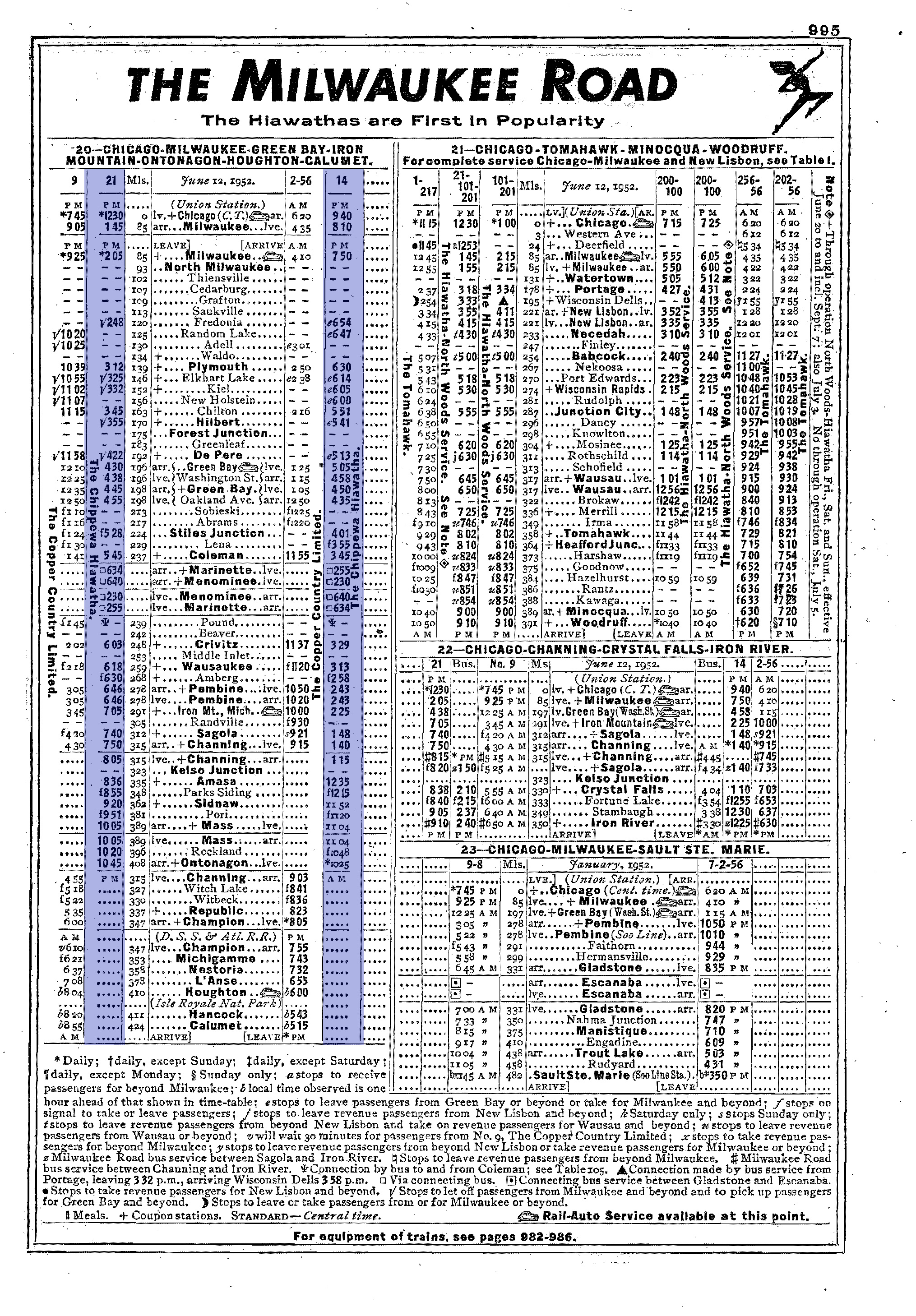

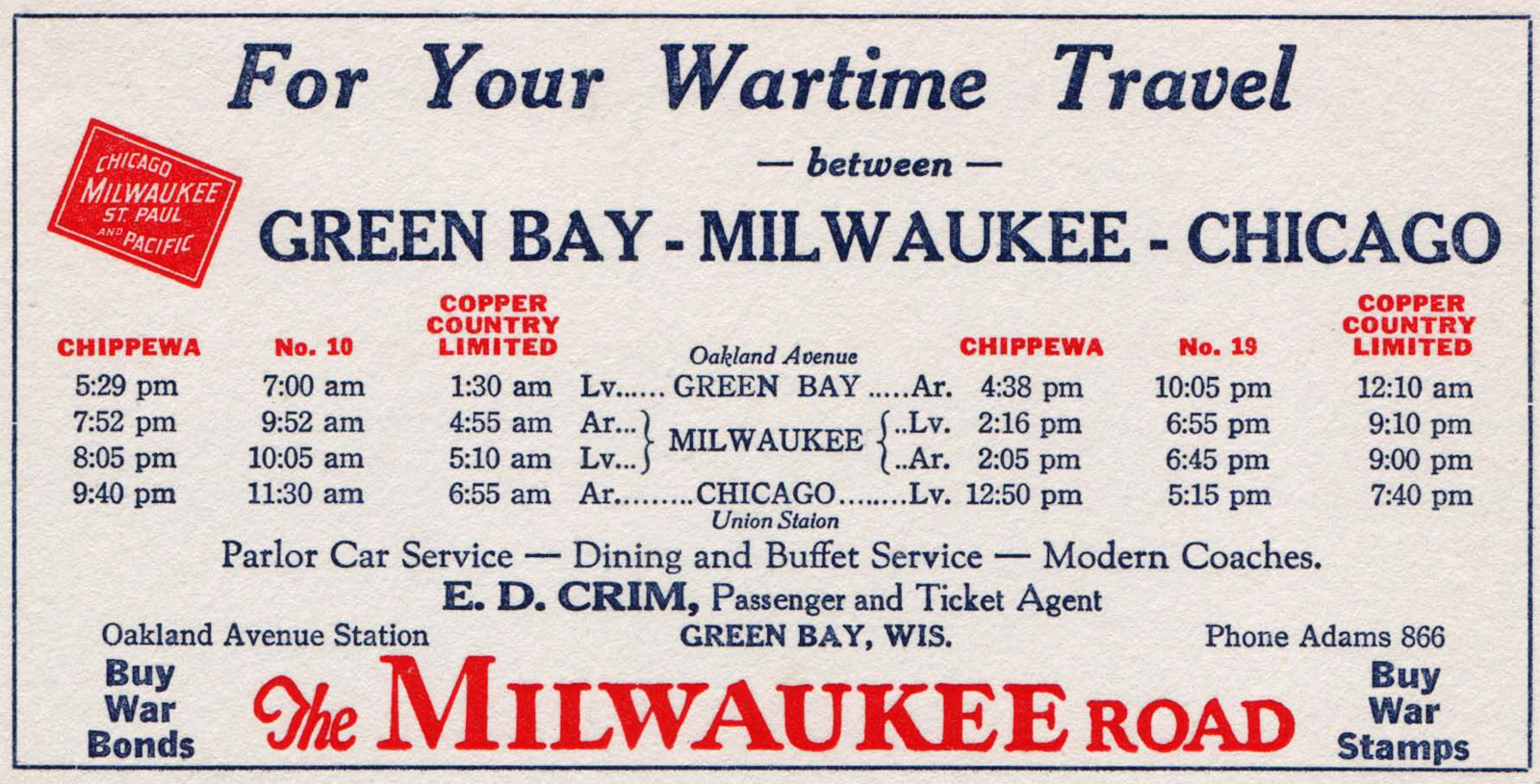

The first to launch was the North Woods Hiawatha between New Lisbon and Minocqua, Wisconsin on April 1, 1937 and then the Chippewa on May 28, 1937 between Chicago and Michigan's Upper Peninsula (the Midwest Hiawatha began on December 11, 1940).

According to the railroad it was, "continuing its campaign to stimulate rail travel through the introduction of high speed passenger service in air-conditioned coaches in territory previously served principally by local trains." The Chippewa's service coverage was a stepped process, involving additional stops over the course of a year.

When it first began the Chippewa served Chicago and Iron Mountain, Michigan (via Green Bay, Wisconsin) but was soon extended to Channing by October.

Finally, the following March (1938) service was pushed to Ontonagon along the shores of Lake Superior, the Milwaukee's furthest reach into the Wolverine State. When rail travel was still the way to get around summer vacationers often used trains to relax in the U.P. and the Milwaukee competed against the Chicago & North Western for this passenger traffic.

The Chippewa was powered by Class F-3-a 4-6-2s. These locomotives wore streamlined shrouding that closely resembled their 4-4-2 and 4-6-4 brethren with a similar livery of grey, maroon, and orange. The work was done, of course, at the fabled shops in Milwaukee and improved upon over the years.

At first the locomotives showcased only streamlined touches but by 1941 they were completely sheathed in steel including "Chippewa" nameplates on the running boards and the sprinting Indian logo on the tender.

Only two Pacifics in all received these elegant touches, #151 and #152. Just like the Atlantics and Hudsons, both 4-6-2s were quite capable at zipping their train up to 100 mph.

One must keep in mind that unlike other railroads the Milwaukee was as much concerned with the incredibly fast speeds of their trains as they were with provided first-class service.

According to Jim Scribbins' book, "The Hiawatha Story," the company had initially chosen steam power on its streamliners for a number of reasons:

- It was best suited to pull the full-size streamlined cars.

- Had flexibility as a non-articulated trainset (when the concept was introduced such single-unit, streamlined diesels were not yet in wide-scale production).

- Existing facilities were already available.

- Proper proportions (as the railroad saw it) among the locomotives and cars

- Steam offered full-horsepower at top speed, was 25% cheaper than diesels, and the steam locomotive design was meant to provide improved grade-crossing protection for crews and passengers.

Milwaukee Road 4-6-2 #151 is seen here in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1954 following its retirement. The locomotive was originally #1539. It was later rebuilt and streamlined, in 1941, to handle the railroad's "Chippewa-Hiawatha" service.

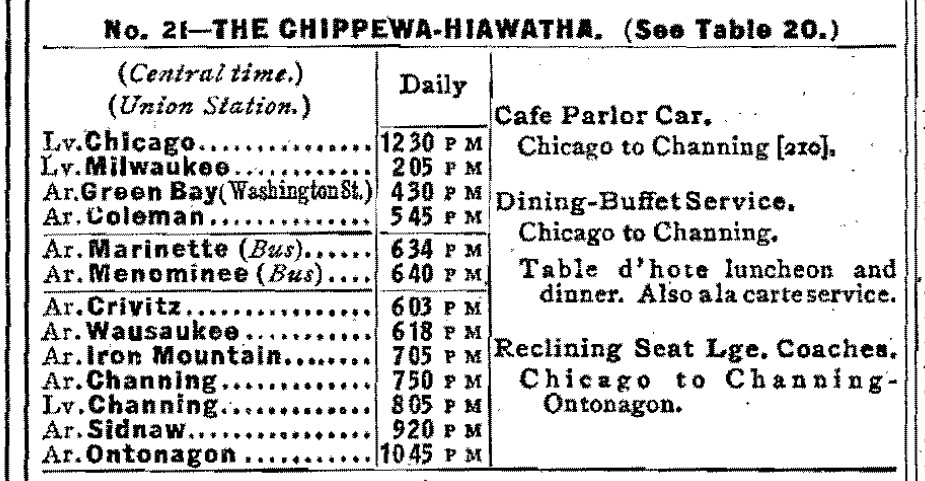

Milwaukee Road 4-6-2 #151 is seen here in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1954 following its retirement. The locomotive was originally #1539. It was later rebuilt and streamlined, in 1941, to handle the railroad's "Chippewa-Hiawatha" service.The Chippewa was listed as trains #14 (southbound) and #21 (northbound). During its first ten years of service a parlor and buffet-diner were offered between Channing and Chicago while three, through reclining-seat coaches ran the entire route.

In 1948 the train officially joined the Hiawatha fleet becoming the Chippewa-Hiawatha. According to Tom Murray's, "The Milwaukee Road," upgrades included an RPO-express, three former Olympian Hiawatha reclining-seat coaches, a 1948 diner, and a 1938 "Beaver Tail" parlor car.

Consist (1952)

Interestingly, the Pacifics remained primary power for only two more years and the Chippewa witnessed a brief career between receiving this new equipment and the first changes/cutbacks. In 1950 diesels arrived in the form of Electro-Motive E7As and FP7s while in December of that year through service was truncated no further south than Milwaukee.

Timetable (1952)

Final Years

As the public began abandoning trains for the open highway vacation trains like the Chippewa-Hiawatha were the first to feel the affects (the C&NW's trains fared no better).

During January of 1954 service was further reduced between only Milwaukee and Channing. Finally, the train made its final run on February 6, 1960 as the last secondary Hiawatha still in service when it was discontinued (the former North Woods Hiawatha lost its name in 1956 but carried on via its train numbers until 1970).

Perhaps more than most other roads, as Mr. Solomon and Mr. Gruber note, the Milwaukee invested incredible amounts of time, money, and energy into operating its Hiawathas in an effort to provide top-level, high-speed service. As a result, when traffic began its incessant decline the company pulled the plug on all but its most important corridors to reduce costs.

Sources

- Murray, Tom. Milwaukee Road, The. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2005.

- Scribbins, Jim. Hiawatha Story, The. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road Remembered. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota, 2008 (Second Edition).

- Solomon, Brian and Gruber, John. Milwaukee Road's Hiawatha's, The. St. Paul: Voyageur Press, 2006.

Recent Articles

-

Arizona Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 01:17 PM

Learn about Arizona's rich history with railroads at one of several museums scattered throughout the state. More information about these organizations may be found here. -

Arkansas Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 12:59 PM

The state of Arkansas is home to a handful of small railroad museums. Learn more about these organizations here. -

Alabama Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 16, 25 12:30 PM

Alabama, with its storied past and vibrant connection to the railroad industry, is home to several captivating railroad museums.