Great Locomotive Chase Of 1862: "Andrews' Raid"

Last revised: November 7, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Great Locomotive Chase has become a legendary event that unfolded during the early years of the Civil War, an attempt by Union forces and sympathizers to destroy railroad infrastructure north of Atlanta, Georgia in hopes of eventually capturing the strategic city of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The celebrity locomotive in what also became known as Andrews' Raid was the Western & Atlantic Railroad's General.

The American Type 4-4-0 steamer was commandeered by James Andrews himself (leader of the raid) and used throughout the chase where he traveled northward from Atlanta causing as much damage as he could.

Unfortunately, the hasty Union plans were too slow and disorganized to cause serious damage and most of those involved were eventually captured.

Today, for history's sake the General remains preserved in Kennesaw, Georgia at the Southern Museum of Civil War & Locomotive History.

Photos

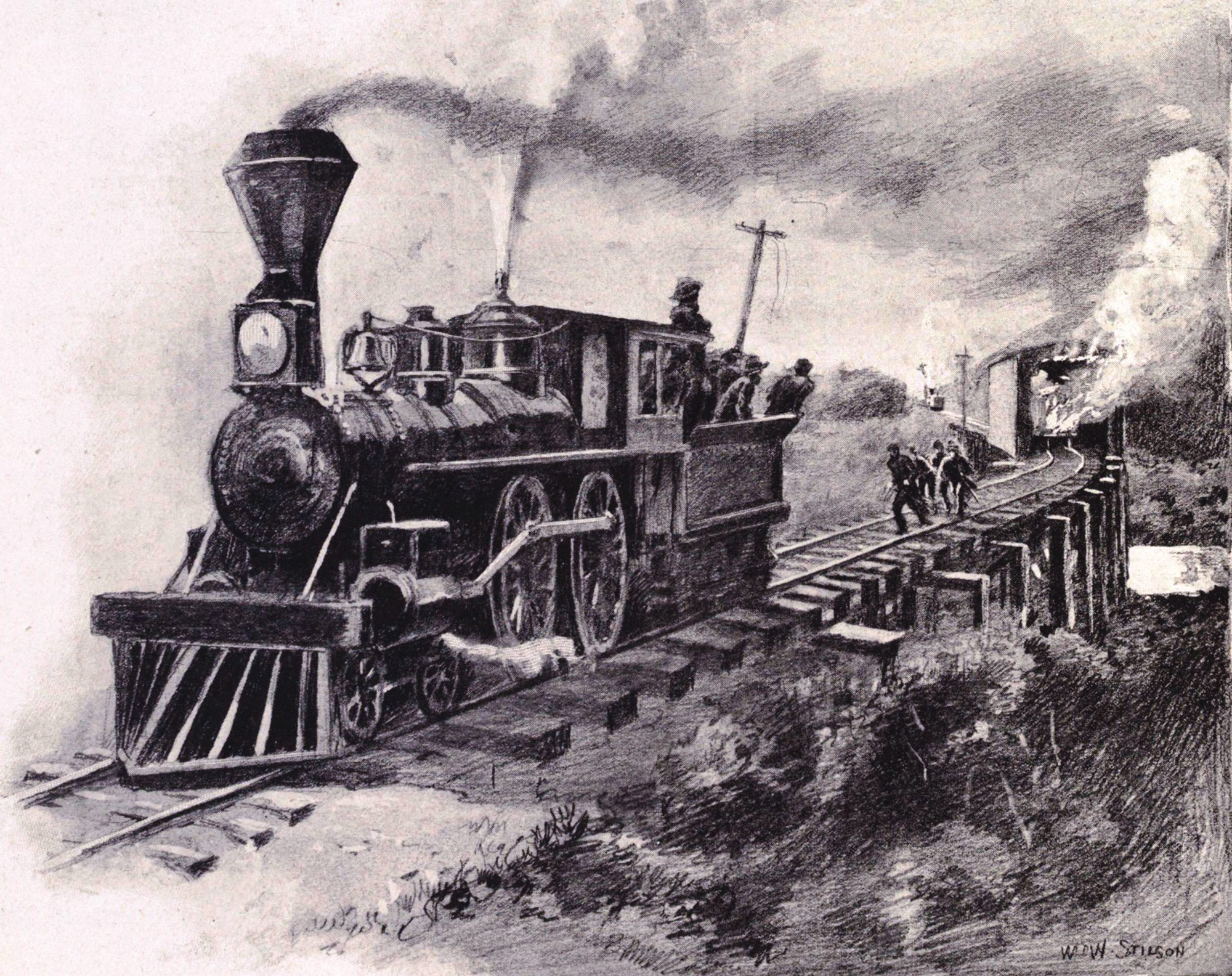

A drawing of the "Great Locomotive Chase." The Union raiders attempted to destroy bridges and trackage behind them to thwart their pursuers.

A drawing of the "Great Locomotive Chase." The Union raiders attempted to destroy bridges and trackage behind them to thwart their pursuers.History

While the Great Locomotive Chase may have ended in Union loyalists failing to complete their goal it was a great example of the determination and bravery exhibited by both sides in fighting for their cause (and ultimately ended in most being recognized for their efforts).

What is also regarded as Andrews' Raid occurred during the early years of the Civil War and was carried out on the morning of April 12, 1862.

Leading the daring attempt was a civilian scout and spy known as James J. Andrews, who as an engineer and two other members of his party were also able-bodied railroaders; William James Knight and Wilson W. Brown (both of whom were privates in the 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry).

Andrews' plan hoped to accomplish two goals, aside from destroying as much Confederate property as possible on his journey north from Atlanta he hoped to aid Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel who was moving his army through Tennessee and eventually hoped to capture the strategically important city of Chattanooga.

Andrews Raid

To pull off the raid Andrews was able to recruit roughly two-dozen soldiers from the 21st and 33rd Ohio Infantries as well as one other civilian, William Hunter Campbell.

The plan was to grab a northbound express passenger train out of Atlanta at the fuel and rest stop of Big Shanty (now known as Kennesaw), so chosen because the location did not have a telegraph, which would allow the raiders more time in executing their mission.

On that fateful morning, the team boarded the Western & Atlantic train at Marietta, Georgia and informed Conductor William Allen Fuller that they were Confederate secret service agents on a special mission for General Beauregard.

While somewhat wary of the story, especially of Confederate deserters, Fuller allowed the men to board the train without much of an issue.

Once the train had stopped at Big Shanty and the passengers and crew were enjoying breakfast at the next-door Lacy Hotel Andrews' team sprang into action (aside from the hotel the only signs of life at this location along with the depot was Confederate Camp McDonald).

Locomotives Involved

The train was led by the General, a 4-4-0 American type locomotive built by the Rogers Locomotive Works of Patterson, New Jersey in 1855. Additionally, the consist included two passenger cars and three empty boxcars.

It is somewhat shocking that Andrews' team was even able to steal the train as sentries were posted not far away. Nevertheless, William Pittenger and some of the other men uncoupled the passenger cars then hopped in the boxcars while Andrews, Knight, Brown, and another individual (who would work as the fireman) jumped in the cab of the General and off they went.

Western & Atlantic 4-4-0 #3, the "General," and Louisville & Nashville combine #665, the "Jim Crow," host a photo special on the L&N in July, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.

Western & Atlantic 4-4-0 #3, the "General," and Louisville & Nashville combine #665, the "Jim Crow," host a photo special on the L&N in July, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.From the hotel Fuller could see that his train was being stolen and immediately raced after it on foot along with engineer Jeff Cain and W&A Locomotive Superintendent Anthony Murphy (in this era locomotives usually did not travel faster than 15 to 20 mph at-speed).

As the General gained speed the pursuers realized that catching it on the run would not possible so they grabbed a nearby handcar (a manually powered track car) and continued on. Not far up the line Andrews stopped quickly at Allatoona to cut telegraph wires and pull up a few rails.

Unfortunately, due to their pursuers and lack of manpower the raiders did not have enough time to cause any serious property damage (such as burning bridges, razing other buildings, or tearing up large sections of track).

For instance, not far up the line at Etowah sat the locomotive Yonah as well as a bridge. Andrews wanted to destroy both but lack of time forced him to steam on, and only received waves from the soldiers and passengers waiting at the small depot who were unaware of what was happening.

During the Civil War the railroad industry was still considered in its infancy although even by that time operations had become increasingly sophisticated including having strict timetables, which had to be closely adhered, to avoid collisions.

Andrews had acquired a timetable for the Western & Atlantic line and thus knew when to expect a train although this still meant he had to pull his train into sidings to meet oncoming traffic such as at the W&A yard in Kingston.

Here, Andrews met the southbound train from Rome, Georgia and its crew began inquiring as to the whereabouts of Conductor Fuller and the rest of the train.

Again, Andrews quick thinking got him out of trouble as he explained the train was rushing northward to resupply Beauregard with ammunition, a story that was very believable since it was an express run anyway with few station stops.

At A Glance

Unfortunately, Andrews could not have predicted the tenaciousness of Fuller who had acquired his own locomotive, the Yonah, and was now in hot pursuit of his train.

The raiders were also running into another predicament; as they waited in Kingston for another southbound freight to pass they learned that there several extras behind it (denoted by a red flag at the end of each train).

As Andrews learned through a conductor on one of the trains, Confederate forces had learned that General Mitchel planned to march towards Chattanooga and Beauregard was moving as much equipment out of the city as possible.

This long delay nearly allowed Fuller and the Yonah to catch the raiders, as he learned at Kingston he was just minutes behind them.

Unfortunately, the yard was full of traffic and Fuller and his crew abandoned their locomotive there, instead opting to catch the next northbound run out of the yard.

At Adairsville they saw more signs of damage left behind by the raiders but the engineer of the locomotive Texas, Peter Bracken, handed his steamer off to Fuller's team who were in such a hurry that they did not even bother to turn it around.

Time was running out for Andrews and his raiders; by the time they reached Calhoun the whistle of the Texas could be heard in the distance.

At Dalton, Fuller's on-board telegrapher was able to get a message through to Chattanooga about the incident just before the raiders cut the line.

(Thanks to "The Great Locomotive Chase" by Rosemary Entringer, from the May, 1956 issue of Trains as a primary reference for this article.)

Another view of Western & Atlantic 4-4-0 #3, the "General," and combine #665 hosting a photo charter on the Louisville & Nashville in July, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.

Another view of Western & Atlantic 4-4-0 #3, the "General," and combine #665 hosting a photo charter on the Louisville & Nashville in July, 1970. American-Rails.com collection.Postscript

With forces now approaching from both north and south Andrews' team was desperate; they tried to burn the bridge at Chickamauga with an oil-soaked boxcar but it would not catch.

Finally, at milepost 116.3 (just 18 miles south of Chattanooga) with the General out of fuel and water the team abandoned the locomotive and took off through the Georgia countryside on foot, every man for himself.

Most of the group, including Andrews, was later captured although some managed to escape back to Union lines. The fate of those who were captured was mixed; some escaped, others were exchanged for Confederate POWs, and a few including Andrews were hung as spies.

A handful of the Union soldiers were awarded the Medal Of Honor, many posthumously, although Andrews was not eligible as a civilian.

Additionally, the Governor of Alabama commended many on the Southern side for their bravery, including Conductor Fuller. Today, the General is a permanent reminder of all those involved in the legendary Great Locomotive Chase.

Recent Articles

-

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In New Jersey

Apr 10, 25 09:40 PM

This guide highlights passenger train services currently available throughout the state of New Jersey. -

Rio Grande 4-6-6-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 10, 25 12:47 PM

The Rio Grande owned some large wheel arrangements, including the 4-6-6-4s. Interestingly, the railroad was never satisfied with these engines. -

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In Michigan

Apr 10, 25 12:06 PM

Michigan offers a variety of passenger train services, allowing travelers to discover the state's beauty and charm in a relaxed and comfortable manner. Learn more here.