Canadian Pacific Railway: Map, History, Logo, Photos

Last revised: August 22, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Only two North American railroads can claim the status of true, transcontinental carriers and both are located in Canada. Of these just one was privately-funded and has been privately-owned since its inception, Canadian Pacific.

In addition, CP can now claim status as the only Class I with direct, north-south service from Canada to Mexico, via the United States. In a deal announced by Bloomberg on March 21, 2021 it acquired Kansas City Southern for $25 billion.

Canadian Pacific was the country's first and its story is impressive, even when compared to great U.S. systems like the Pennsylvania, New York Central, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific.

The CP initially linked Winnipeg with the Pacific coast in British Columbia. Only later did it push east to the Maritimes, doing so very quickly.

- On March 21, 2021 Canadian Pacific announced it would be acquiring Kansas City Southern for $25 billion. The new railroad to emerge will be known as Canadian Pacific-Kansas City.

While rival Canadian National made a counterproposal of $33.7 billion to acquire KCS, CN's attempted acquisition was killed by the Surface Transportation Board on August 31, 2021. The new CP-KCS merger formally took place on April 14, 2023. -

As Tom Murray notes in his book, "Canadian Pacific Railway," its construction in many ways helped establish a unified country as disassociated provinces banded together under the threat of an American takeover.

Canadian Pacific's traffic base has always been diversified but grain still plays an important role just as it did a century ago.

Photos

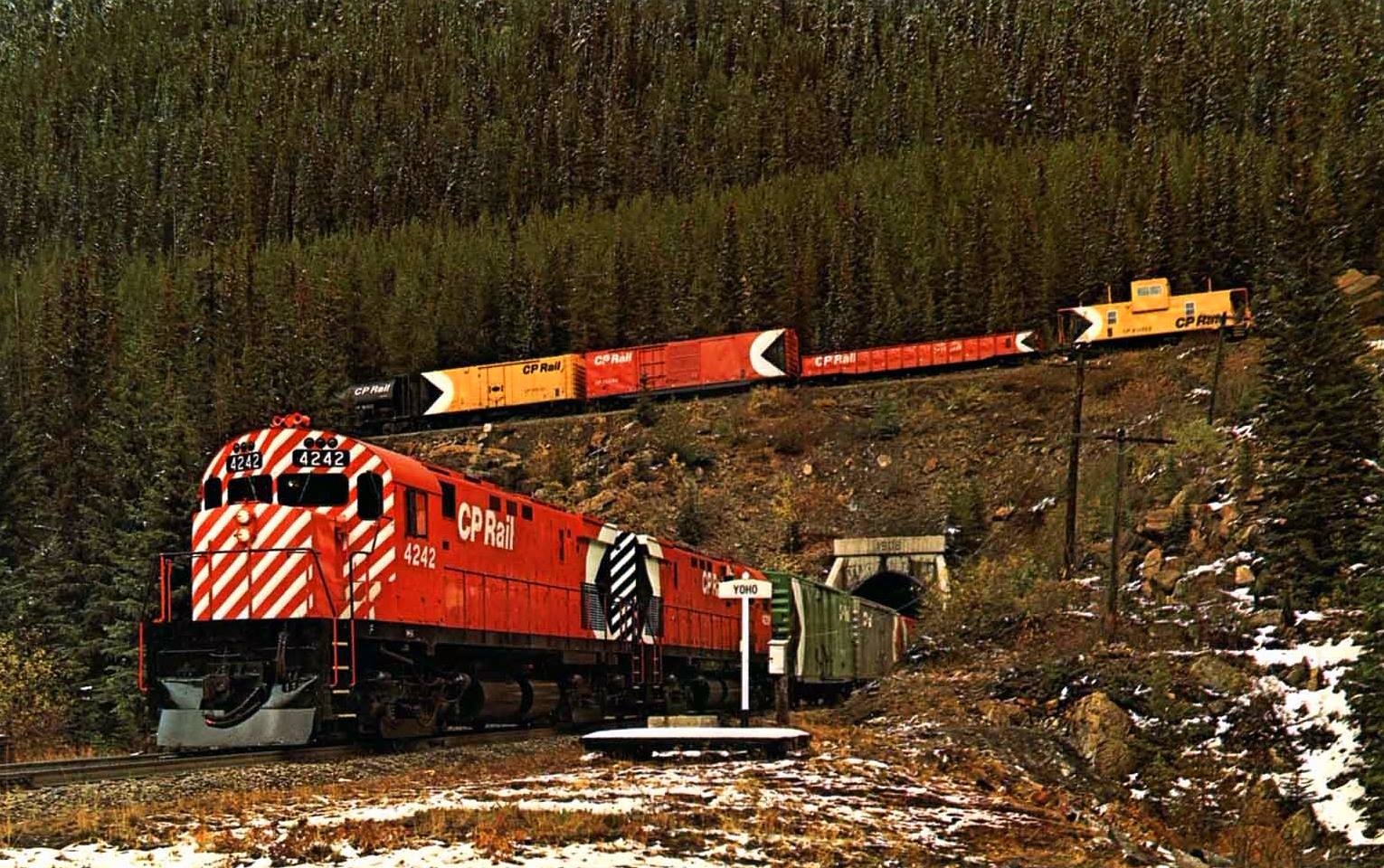

A Canadian Pacific publicity photo featuring C424's passing through the Spiral Tunnels while crossing beneath their own train on Kicking Horse Pass within the Canadian Rockies (Alberta/British Columbia border) in 1968.

A Canadian Pacific publicity photo featuring C424's passing through the Spiral Tunnels while crossing beneath their own train on Kicking Horse Pass within the Canadian Rockies (Alberta/British Columbia border) in 1968.History

At its peak, CP boasted an astounding network of more than 17,000 route miles while maintaining a hand in numerous other industries from ocean shipping to telecommunications.

Today, its system is much smaller but still commands a dominating presence in its home country. In addition, it serves New England, the Twin Cities, Chicago, and as far south as Kansas City.

Much like the Union Pacific and Central Pacific helped bolster a growing United States through completion of the Transcontinental Railroad so too did the Canadian Pacific in its native lands. For CP, it held even greater importance as it unified a young nation.

At A Glance

17,000 (1950) 14,700 (2020) | |

Following the American Civil War, U.S. railroads were on the move and had achieved a national network greater than 50,000 route miles by 1870. The decade's great achievement, of course, was UP's and CP's accomplishment at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869.

Two major players in the American West, Jay Cooke and James J. Hill (the "Empire Builder"), strongly considered pushing new routes across the northern border. In addition to their efforts, other Americans were involved with construction projects in the eastern provinces.

Outside of railroad development there were whispers the U.S. would continue expanding by grabbing not only what is now British Columbia but also potentially all of British North America. This became a very real possibility when America struck a deal with Russia to acquire the territory of Alaska.

Alarmed, the British provinces quickly unified between July 1, 1867 when the Dominion of Canada was formed (celebrated every July 1st as "Canada Day") and July 19, 1871 when British Columbia officially joined the new centralized government.

Logo

Formation

Afterwards, efforts to link Canada by rail were immediately put forth. One particularly important but fleeting figure in this endeavor was Sir John A. Macdonald who headed the country's Conservative Party.

He helped get things started by playing a key role in the Canadian Pacific Railway's formation in February of 1873.

This early version held considerable American ties, which would have placed the route heading west from the northern Great Lakes region through Michigan's Upper Peninsula, northern Wisconsin and northeastern Minnesota.

Angered and irritated Canadians wanted nothing to do with this plan which would have likely resulted in an American takeover at some point.

Wishing only for a truly Canadian route the original CP scheme died; after nearly a decade hope was renewed when strong leadership through George Stephen, president of the Bank of Montreal, led to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company's incorporation on February 16, 1881.

Later that year he was joined by William Cornelius Van Horne, another Yankee who became CP's first general manager and oversaw much of the railroad's initial construction.

Canadian Pacific E8A #1800, one of three the railroad rostered, is stopped with its train in Ottawa, Ontario during November, 1968. Author's collection.

Canadian Pacific E8A #1800, one of three the railroad rostered, is stopped with its train in Ottawa, Ontario during November, 1968. Author's collection.James Hill still carried some influence at this time as he continued pushing for a more southerly routing to connect with his Saint Paul & Pacific (predecessor of the Great Northern) in the Upper Midwest.

After he realized these efforts were in vain, Hill disassociated himself from the project and became CP's fiercest rival until Canadian National's creation.

The railroad's route was projected to begin at Callander, Ontario (interchanging at that point with the Canada Central Railway) and head west some 1,900 miles into British Columbia.

The region's desolation added to construction difficulties, a problem which American systems like Union Pacific, Central Pacific, and Northern Pacific also faced. For the most part the only way to receive construction materials and other equipment was either via horseback or watercraft.

Adding to the struggles was the extremely rugged topography which included the inhospitable Laurentian Shield (sometimes known as the Canadian Shield it covers much of the Hudson Bay region with thick forests, rocky outcroppings, rivers, marshes, bogs, and numerous lakes) to the east and the impenetrable Rocky Mountains to the west (western Alberta and most of British Columbia).

Undaunted, promoters pushed ahead and began construction from several different points with the entire cost projected at $25 million. As an added incentive the government provided 25 million acres of land grants.

Work was launched from the west in May of 1880 at a point known as Yale, British Columbia along the Fraser River. Andrew Onderdonk, an American from New York, was tasked with engineering the first segment to run 127 miles east where it would terminate at Kamloops Lake.

The line he selected ran north through the Fraser Canyon before turning northeastward along the Thompson River Canyon where it hugged the eastern bank into Kamloops Lake. The eastern segment was a route chosen by Major Albert Bowman (A.B.) Rogers, another American from Massachusetts.

Heading west from Calgary, Alberta it followed the Bow River where it then crossed the Rockies at what became known as Kicking Horse Pass at an elevation of 5,338 feet. From here it followed the Kicking Horse River south and then turned west into the small community of Golden which also lay along the Columbia River.

The line next crossed Rogers Pass (located within the Selkirk Mountains within what is now Glacier National Park of Canada) then hugged the Illecillewaet River into Revelstoke before again meeting the Columbia where the river was bridged.

From this point it continued westward through Eagles Pass, skirted Shuswap Lake and finally met Onderdonk's section at Kamloops. While the line would penetrate some of the most unforgiving country found anywhere in North America its beauty also rivaled any railroad in the western United States.

Canadian Pacific 2-8-2 #5145 in service at Montreal during the 1950s. This particular unit was built by CP's own shop forces in 1926. American-Rails.com collection.

Canadian Pacific 2-8-2 #5145 in service at Montreal during the 1950s. This particular unit was built by CP's own shop forces in 1926. American-Rails.com collection.The central leg between Calgary and Winnipeg, Manitoba (more than 800 miles) was finished relatively quickly through territory that was not particularly arduous. It was ready for service by August of 1883. Not surprisingly, the mountainous region needed more time even with 10,000 men working on the project.

As crews continued west beyond Calgary, Onderdonk pushed east from Yale reaching Kamloops Lake in September of 1885.

Just a few months later, on November 7th, his counterparts arrived at a point known as Craigellachie (a name honoring Craigellachie, Moray, a small village in Scotland which was George Stephen's ancestral home).

During a rather low-key last spike ceremony the event signaled the Canadian Pacific's completion. Its eastern section between Winnipeg and Callander, via Port Arthur, had already been finished earlier that May.

While CP's opening was an important footnote in Canada's history, much work remained to transform the railroad into a profitable venture.

To save money its routes, particularly within British Columbia, were built hastily featuring steep grades over 4% and generally light construction. In addition, the sparsely populated western provinces offered only marginal profit potential.

If they hoped to achieve long-term success officials realized two things were needed; pushing further eastward into the country's developed provinces and modernizing their network.

Canadian Pacific C424 #4201 is seen here laying over between assignments at hte St. Luc Yard in Montreal, Quebec on March 22, 1970. Roger Puta photo.

Canadian Pacific C424 #4201 is seen here laying over between assignments at hte St. Luc Yard in Montreal, Quebec on March 22, 1970. Roger Puta photo.Arguably no other railroad grew faster than CP between 1885 and the century's end. Thanks in large part to Stephen's efforts; the railroad added an incredible 2,500 miles during this period. Its rate of expansion was phenomenal as it rapidly added corridor after corridor east of the Great Lakes.

William Kaye Lamb notes in his book, "History Of The Canadian Pacific Railway," initial plans called for CP and Grand Trunk (future component of Canadian National Railways) to work together in providing transcontinental service across the country.

The former would serve the western territories while the latter connected eastern Ontario with the Maritimes.

However, as previously mentioned, Stephen came to realize that CP's only chance for prosperity was by encroaching into GTR's territory where Ontario and Quebec contained over 70% of the country's total population at that time. Naturally, this caused extreme friction. There was the issue of GTR's well-established nature, which would make entry difficult.

At first, Stephen attempted to grab the Great Western Railway linking Windsor with Niagara Falls, Ontario which would have offered a shortcut between Buffalo, New York and Detroit, Michigan.

Unfortunately, Grand Trunk officials outmaneuvered his attempt, acquiring the road for themselves. Obviously, GTR wanted nothing to do with this growing threat but Stephen persisted nonetheless.

Timetables (1952)

As it turns out, he had two aces up his sleeve. First, CP's original charter carried an option to acquire the Canada Central. This never-built railroad was to extend east of Callander and down the Ottawa River Valley where it would terminate at Ottawa.

CP gained control only months after its own formation and the route opened in August of 1882. Second, Stephen held rights in the small Credit Valley Railway even before CP's incorporation.

This system had established a 121-mile corridor linking Toronto with St. Thomas and was formally leased by CP on November 30, 1883.

The latter town provided a friendly connection with the Canada Southern Railway (CASO), a competitor of GTR's Great Western between Buffalo and Detroit. The CASO was controlled by Michigan Central, a New York Central subsidiary, all of which was under the Vanderbilts' control.

The Grand Trunk had long battled the Vanderbilts in this region, dating back to the 1870's when the two parties fought over the former piecing together a Chicago connection.

All that remained for CP to link Ottawa with Toronto was building the dormant Ontario & Quebec Railway. Its heritage dates back to an 1871 incorporation and its charter was owned by Stephens' allies. The 193.8-mile line was largely completed by August of 1884.

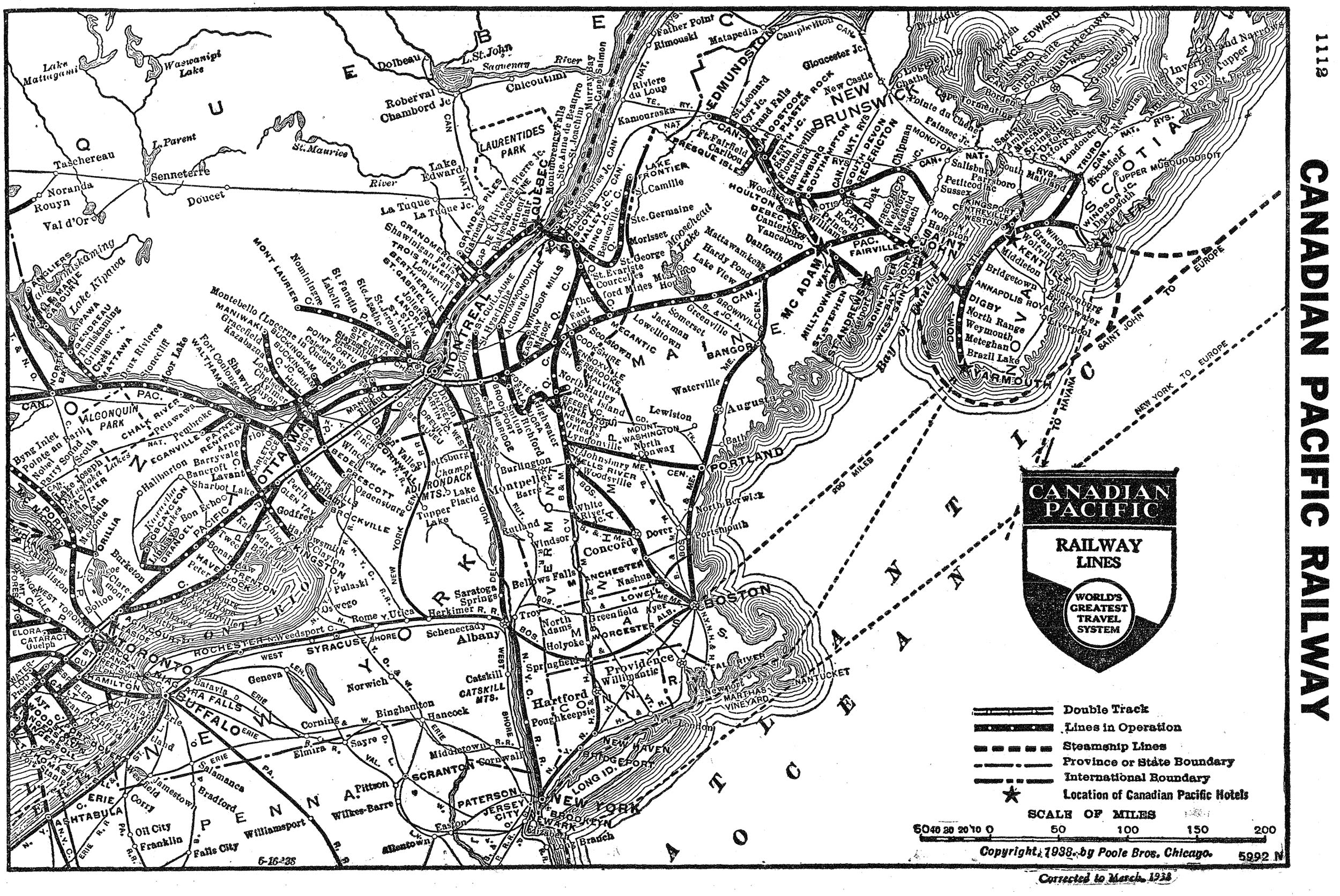

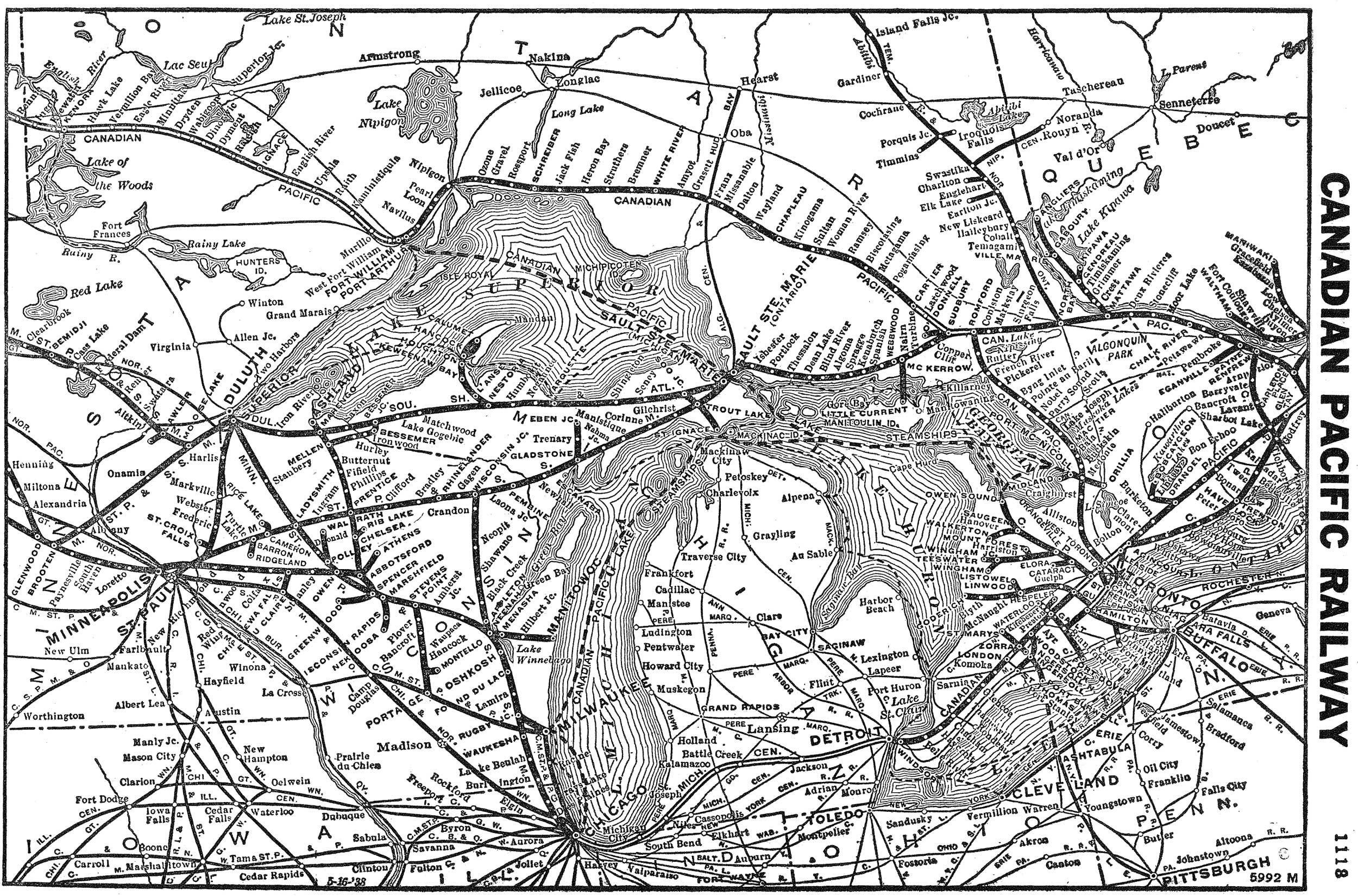

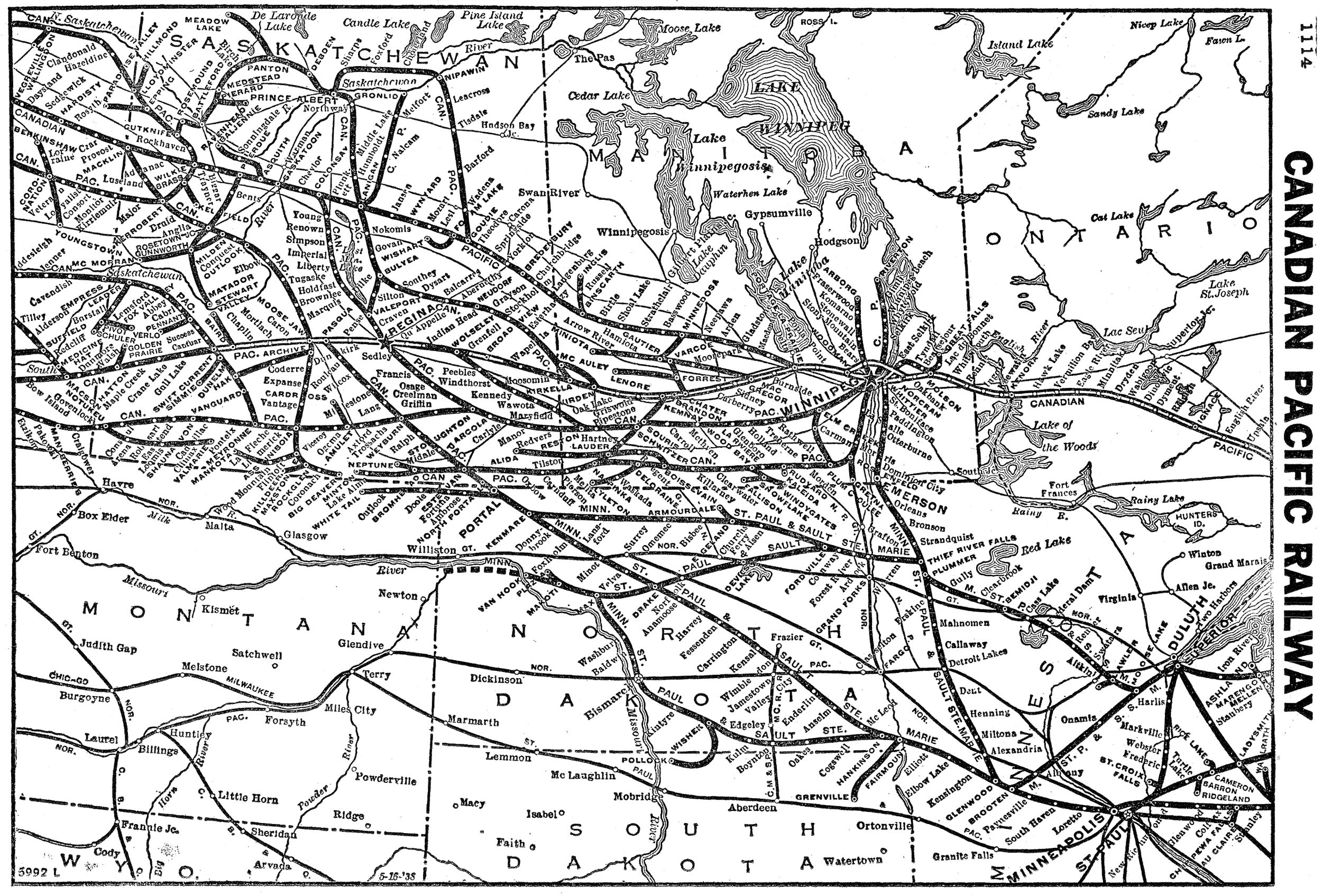

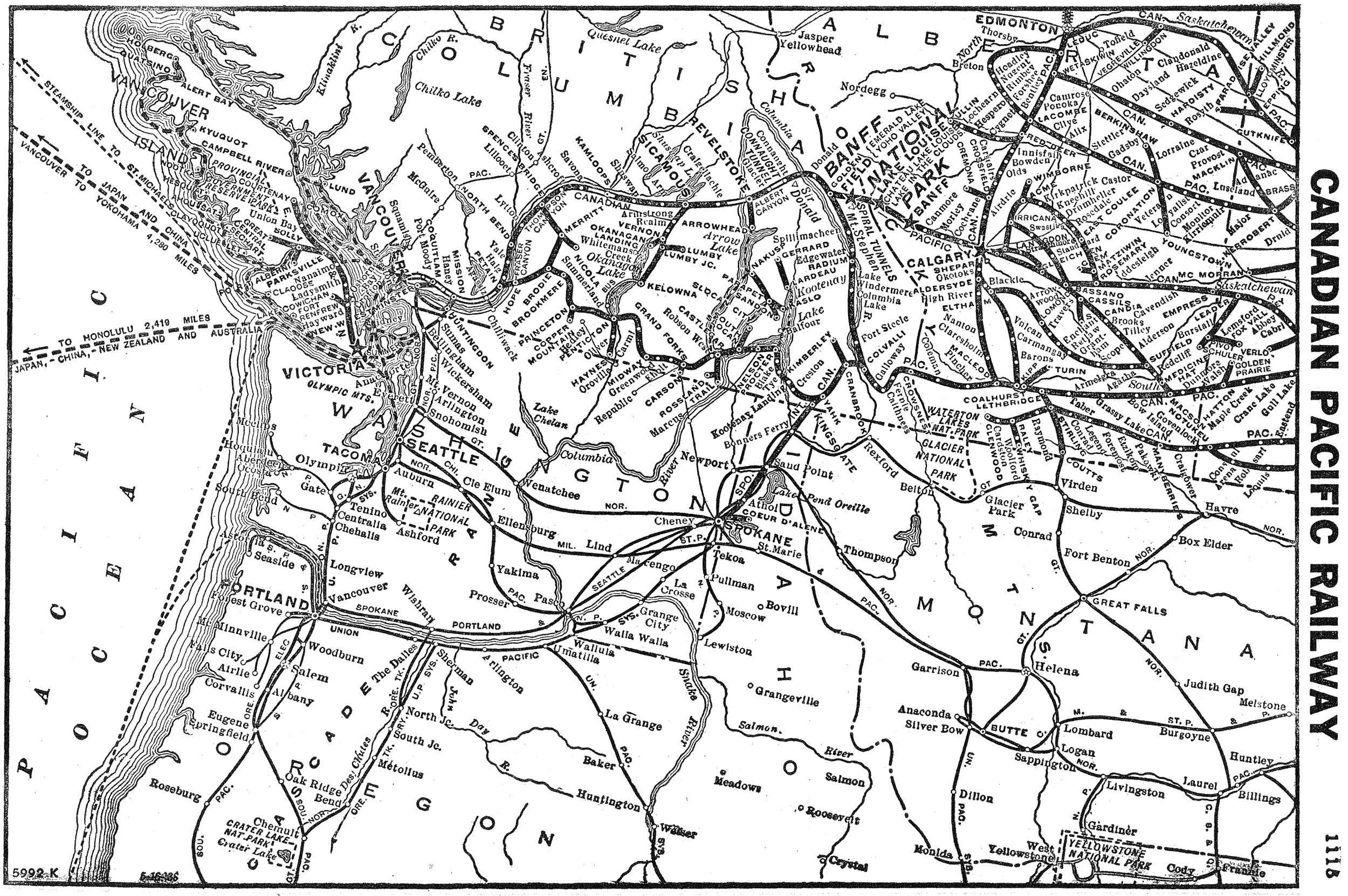

System Map (1938)

Two other important additions included the Atlantic & North-West Railway (A&N-W) and the South Eastern Railway, both added in 1883.

The former carried a dormant charter to connect Lake Superior with the Atlantic coast and bridge the St. Lawrence River at Lachine, thus providing direct entry into downtown Montreal.

As Mr. Lamb's book points out federal legislation also stipulated that the A&N-W would lease, "such a portion of the line as may be necessary to carry the Canadian Pacific to the Atlantic Coast."

Specifically, a series of subsidiaries provided a through route from Montreal, across northern Maine, and into New Brunswick. After a few years of construction the first train departed for Saint John on June 3, 1889.

The South Eastern in turn, would give CP a further reach into the United States at Newport, Vermont. From this location an interchange with American lines would offer access to New England ports, notably Boston.

The CP never blanketed the Maritimes like its rival, Canadian National, but the road did extend further through New Brunswick and established service on Nova Scotia.

Canadian Pacific FP9 #1410 with train #1, the westbound "Canadian" (Montreal, Quebec - Vancouver, British Columbia), stopped at Dorval, Quebec on September 6, 1965. Roger Puta photo.

Canadian Pacific FP9 #1410 with train #1, the westbound "Canadian" (Montreal, Quebec - Vancouver, British Columbia), stopped at Dorval, Quebec on September 6, 1965. Roger Puta photo.New England was not CP's only access into the United States. In 1888 it reached Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and a year later established connections with the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie Railway (Soo Line) and Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic (DSS&A) across the St. Marys River in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

In 1890 Canadian Pacific gained control of both systems when it agreed to take on their funded debt. The addition of these carriers provided CP a respectable reach into the American Midwest; while the DSS&A only extended across Michigan's Upper Peninsula as far west as Duluth/Superior the Soo Line's network was much more expansive.

It served the Twin Cities, Milwaukee, Chicago, northern Minnesota, maintained an extension to Winnipeg, accessed parts of the Dakotas, and owned a branch to Whitetail, Montana.

The "Soo Line Railroad" was officially formed on January 1, 1961 by merging the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie; Wisconsin Central (acquired by the Soo in 1909); and Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic under one flag.

For many years the Soo remained a separate corporate entity and even grew in 1985 by purchasing the Milwaukee Road's remnants. In an interesting move, CP attempted to sell its Soo subsidiary soon afterwards but then abruptly changed course and acquired full control in 1990. A year later, the "Soo Line" name disappeared.

The Modern CP

By the turn of the 20th century Canadian Pacific's network was largely complete. Its one notable addition was the 1916 purchase of the 149-mile Spokane International, linking Eastport, Idaho at the U.S. border with Spokane, Washington (the SI was later sold to Union Pacific in the 1950's).

After this time much effort was spent to further upgrade the railroad to handle heavier trains and increase track speeds (heavier rail, ballasting, steel bridges in place of wood, etc.). One of the most impressive engineering feats involved improving the grades over Kicking Horse Pass where westbound trains faced a tortuous 4.5% ascent.

John Schwitzer, CP's senior engineer of its western lines, came up with an ingenious solution, a pair of spiral tunnels which essentially wound around themselves; heading west Tunnel #1 was 3,255 feet in length which, at its western bore actually turned the line due north. After passing through Yoho, tracks then crossed the Kicking Horse River where they entered Tunnel #2.

It was 2,921 feet and wound its way north, east, then south and passed beneath itself before again crossing the river. The spectacular design reduced the eastern ruling grade to just 2.2% and the Spiral Tunnels became an oft-photographed location. The new line officially opened for business on September 1, 1909.

Canadian Pacific 4-6-2 #2389, one of the G3 variants capable of dual service assignments, works freight service at Portage la Prairie, Manitoba during the 1950s. Paul Meyer photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Canadian Pacific 4-6-2 #2389, one of the G3 variants capable of dual service assignments, works freight service at Portage la Prairie, Manitoba during the 1950s. Paul Meyer photo. American-Rails.com collection.Following this work, nearby Rogers Pass was also improved as well as Crowsnest Pass to the south. The former included 5-mile Connaught Tunnel which passed through Mount Macdonald, thus lowering the summit by 540 feet (it also eliminated more than 2,300 degrees of curvature), and opened during December of 1916.

The latter involved a breathtaking bridge, 5,328 feet in length and 314 feet high, to span the Oldman River Canyon near Lethbridge. It was Canada's highest railroad bridge at the time and opened on November 3, 1909.

The contemporary Canadian Pacific was much more than just a railroad. It operated a very successful cruise line (Canadian Pacific Steamships Limited) and a large hotel chain.

In 1930 CP got into the airline business by purchasing Canadian Airways Limited. It eventually formed its own such enterprise in 1942, Canadian Pacific Air Lines, which blossomed into a worldwide venture.

By the postwar period CP was a true, multi-modal company, something American railroads could never enjoy due to federal antitrust laws. Unlike rival Canadian National, CP has historically always been a profitable carrier.

But the two do share some historical similarities; both were late to fully dieselize (CP completed the task in 1960) and both operated a wide range of first-generation models from American Locomotive, Electro-Motive, Fairbanks Morse, and Baldwin.

To remain profitable amid shifting traffic patterns CP entered the intermodal business with trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) service launched in 1952.

This later transitioned to container-on-flatcar (COFC) that remains widespread today. In 1977 VIA Rail was established as a CN subsidiary to handle country-wide passenger services, including those of Canadian Pacific.

It was essentially Canada's version of America's Amtrak created in 1971. A year later, in 1978, VIA Rail became a separate corporate entity (a "Crown" corporation), which completely freed CN's financial burden of rail travel.

As the years passed, CP continued to expand into other industries including oil/gas, timber, steel, paper, real estate, and even telecommunications. All of these were profitable with CP's main headquarters situated in Montreal.

As it continued to grow a holding company known as Canadian Pacific Investments Limited was formed in 1962. This was followed less than a decade later by an entire corporate name change to Canadian Pacific Limited in 1971.

The purpose was to better reflect the company's wider scope and saw the rail division referred to as "CP Rail." For purposes of marketing and clarity this changed two decades later when it returned to its original name as "Canadian Pacific Railway" in 1997. At its peak, CP maintained a system of 17,241 miles within Canada (achieved in 1936).

After the government passed the National Transportation Act in 1967, similar to the America's Staggers Act of 1980, Canadian railroads had greater freedom in abandoning or selling unprofitable lines, which CP took full advantage of.

Passenger Trains

Canadian: (Montreal - Vancouver)

Alouette/Red Wing: (Boston - Montreal)

Atlantic Limited: (Montreal – Halifax)

The Viger: (Montreal – Quebec)

The Frontenac: (Montreal – Quebec)

RDC Service

Toronto – Buffalo – New York

Montreal – Quebec

Montreal – Mont-Laurier

Montreal – Ottawa

Sudbury – White River

During the 1980's and 1990's the road shed thousands of miles. Today it ranks sixth among the seven Class I railroads in annual revenue. However, with its diversified holdings and strategic routes the carrier will surely be at the forefront of any potential mega-mergers moving forward.

Kansas City Southern Merger

While full integration of Soo Line and addition of the former Milwaukee Road lines greatly bolstered CP's network, the announcement of its Kansas City Southern acquisition on March 21, 2021 was on another level entirely.

The KCS addition will boast CP's network to 20,000 miles with nearly 20,000 employees and an annual revenue of about $8.7 billion.

Initially, Bloomberg stated KCS investors received 0.489 of a CP share and $90 in cash for each share they hold, valuing the stock at $275 apiece.

However, following CN's attempted bid for KCS which was ultimately denied by the STB, CP was forced to sweeten the deal.

According to Railway Age "...each share of KCS common stock would be exchanged for 2.884 CP common shares and $90 in cash.

In addition, holders of KCS preferred stock would receive $37.50 in cash for each share of KCS preferred stock held. CP’s merger proposal values KCS at $300 per share, representing a 34% premium, based on the KCS unaffected closing share price of $224.16 as of March 19, 2021 and CP’s closing share price of C$91.50 as of August 9, 2021. The proposed transaction includes the assumption of $3.8 billion of outstanding KCS debt."

The new railroad will be known as Canadian Pacific-Kansas City (CP-KC).

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rio Grande 2-8-2 Locomotives (Class K-28): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 10:24 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-28 Mikados were its newest narrow-gauge steam locomotives since the Mudhens of the early 1900s. Today, three survive. -

Rio Grande K-27 "Mudhens" (2-8-2): Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 14, 25 05:40 PM

Rio Grande's Class K-27 of 2-8-2s were more commonly referred to as Mudhens by crews. They were the first to enter service and today two survive. -

C&O 2-10-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 13, 25 04:07 PM

Chesapeake & Ohio's T-1s included a fleet of forty 2-10-4 "Texas Types" that the railroad used in heavy freight service. None were preserved.