Camelback Locomotives: Photos, History, Survivors

Last revised: August 25, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The 'Camelback' locomotive, a general term for the Camel and Mother Hubbard, is a unique steam engine type that emerged in the latter part of the 19th century, mainly in the United States.

Its distinctive design was marked by having the engineer's cab perched atop the boiler, rather than at the rear as is commonly seen in traditional configurations.

This positioning resulted from the unusual width of the locomotive's firebox, which was designed to burn anthracite coal waste - culm - a fuel that was both cost-effective and abundant in certain regions.

Camelbacks represent a uniquely distinct chapter in the design of steam locomotives. While they might not be hailed as the pinnacle of safety, their design stands out markedly among the more conventionally structured locomotives.

Photos

A colorized photo of Philadelphia & Reading 4-2-2 #378, circa 1896, soon after the locomotive was completed. Listed as Class 378 she was built by Burnham, Williams & Company (Baldwin) and the only example in this class the railroad rostered. American-Rails.com collection.

A colorized photo of Philadelphia & Reading 4-2-2 #378, circa 1896, soon after the locomotive was completed. Listed as Class 378 she was built by Burnham, Williams & Company (Baldwin) and the only example in this class the railroad rostered. American-Rails.com collection.Development

Unlike specific wheel arrangements such as the 4-6-2 Pacific or the 2-8-4 Berkshire, which are categorized based on their wheel configurations, the term "Camelback" is specifically used to denote a unique design feature witnessed in certain steam locomotives. This feature undeniably sets them apart in the rich tapestry of locomotive history.

Camelbacks, though ultimately banned due to safety concerns in the early 20th century, initially garnered significant success among anthracite coal carriers.

These locomotives were particularly advantageous because they were engineered to burn a cheap and abundant byproduct of anthracite coal known as culm. This not only optimized resource use but also significantly cut fuel costs.

There were two distinctive types of Camelbacks, the "Camel" and "Mother Hubbard."

Camel Type

The Camel steam locomotives, conceptualized and constructed by the innovative engineer Ross Winans in the late 1840s, represent a remarkable chapter in the history of railway technology.

Named for their distinctive design, these locomotives featured the cab perched atop the boiler, reminiscent of a saddle straddling a camel's hump. This unique configuration integrated a relatively narrow firebox nestled between the driving wheels.

Predominantly adopting an 0-8-0 wheel arrangement, Camel locomotives boasted a centrally positioned cab. This strategic placement was crucial, enabling the distribution of maximum weight directly over the driving wheels, thereby enhancing traction and stability.

Winans, a visionary in locomotive design, eschewed the use of leading or trailing wheels, a decision rooted in his preference to maintain substantial weight on the drivers to optimize locomotive performance.

Initially dubbed "Camels," these locomotives were occasionally referred to as "Camelbacks," though this nomenclature might be considered a misnomer.

These groundbreaking machines carved a niche for themselves in the annals of locomotive engineering, reflecting Winans' legacy of innovation and his enduring impact on rail transportation.

Mother Hubbard Type

The Mother Hubbard design, emerging prominently after 1877, were distinguished by an innovative design that positioned the cab at the front, ahead of an unusually large firebox.

This architectural necessity arose because the considerable size of the firebox precluded the traditional placement of the cab around it. The expansive firebox, known as the Wootten firebox, was specifically engineered to accommodate larger quantities of low-grade coal, thus addressing the challenges of fuel efficiency and cost.

The nomenclature "Mother Hubbard" for these locomotives remains a bit of a mystery, as the origin of this distinctive name is not definitively documented.

Additionally, these locomotives are sometimes referred to as "Camelbacks," although this is a general term only for the center-cab design.

Nonetheless, the Mother Hubbard locomotives stand out in the annals of railroad history for their unique design solution to the practical issue of fuel utilization, showcasing an important evolution in steam locomotive development. Most so-called "Camelbacks" operated throughout the United States were technically Mother Hubbard designs.

John E. Wootten

The innovative Camelback design catapulted John E. Wootten into fame, thanks to his patented Wootten firebox, which was a critical component of the locomotive's unique configuration. Today, the legacy of these distinctive design is preserved in at least five non-operational models displayed across the United States, serving as a testament to a fascinating phase of railroad history.

Camelbacks, with their distinctive features, were prominently utilized by numerous anthracite roads including the Jersey Central, Reading, Lackawanna, Delaware & Hudson, Lehigh Valley, Lehigh & New England, among others. Interestingly, the use of Camelbacks was not restricted to the eastern United States.

The locomotive also made its mark well beyond the anthracite-rich territories, finding utility on prominent lines such as the Santa Fe; Baltimore & Ohio; Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy); Chicago & Eastern Illinois; Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis; New York, Susquehanna & Western; Southern Pacific; Union Pacific; and Wheeling & Lake Erie.

This widespread adoption underscores the versatility and appeal of the Camelback design across diverse geographic and operational contexts.

Jersey Central 4-4-2 #592, a "Camelback" design, makes a quick stop at Bound Brook, New Jersey as folks gather around on May 1, 1954. The locomotive was on its way to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum where it still resides today. Douglas Wornom photo.

Jersey Central 4-4-2 #592, a "Camelback" design, makes a quick stop at Bound Brook, New Jersey as folks gather around on May 1, 1954. The locomotive was on its way to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum where it still resides today. Douglas Wornom photo.The genesis of the Camelback can be traced back to an innovative precursor developed by the Baltimore & Ohio in the 1840s, intriguingly named Muddiggers.

However, it wasn't until several decades later that this concept truly gained traction and evolved into the iconic Camelback design. The locomotive received its name for the unique positioning of the cab which sat astride the boiler giving the design a center "humped" appearance.

The creation of the Mother Hubbard is credited to John E. Wootten, whose innovations were driven by the need to efficiently utilize anthracite coal culm—that is, the fine waste product of anthracite mining.

Anthracite coal burned cleaner and hotter than other types, but it was difficult to ignite and required a larger firebox for effective use. Wootten's design, patented in the 1870s, featured a wide firebox that rested on the locomotive's driving wheels.

This offered more space for the fire while distributing weight more evenly. The engineer's cab was located in the center of the boiler, above the firebox.

Mother Hubbards were primarily popular with railroads in the eastern United States, where anthracite coal was predominantly mined, particularly in Pennsylvania.

Railroads such as the Central Railroad of New Jersey, Philadelphia & Reading (Reading), and the Lehigh Valley were among the most prominent users of Camelbacks. The locomotives were best suited for freight routes but were also used for passenger services in some cases.

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western

- Lehigh & New England

- Lehigh & Hudson River

Other lines which came to use the Camelback included the B&O, Erie, Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, Santa Fe, Pennsylvania, Wheeling & Lake Erie, and Maine Central.

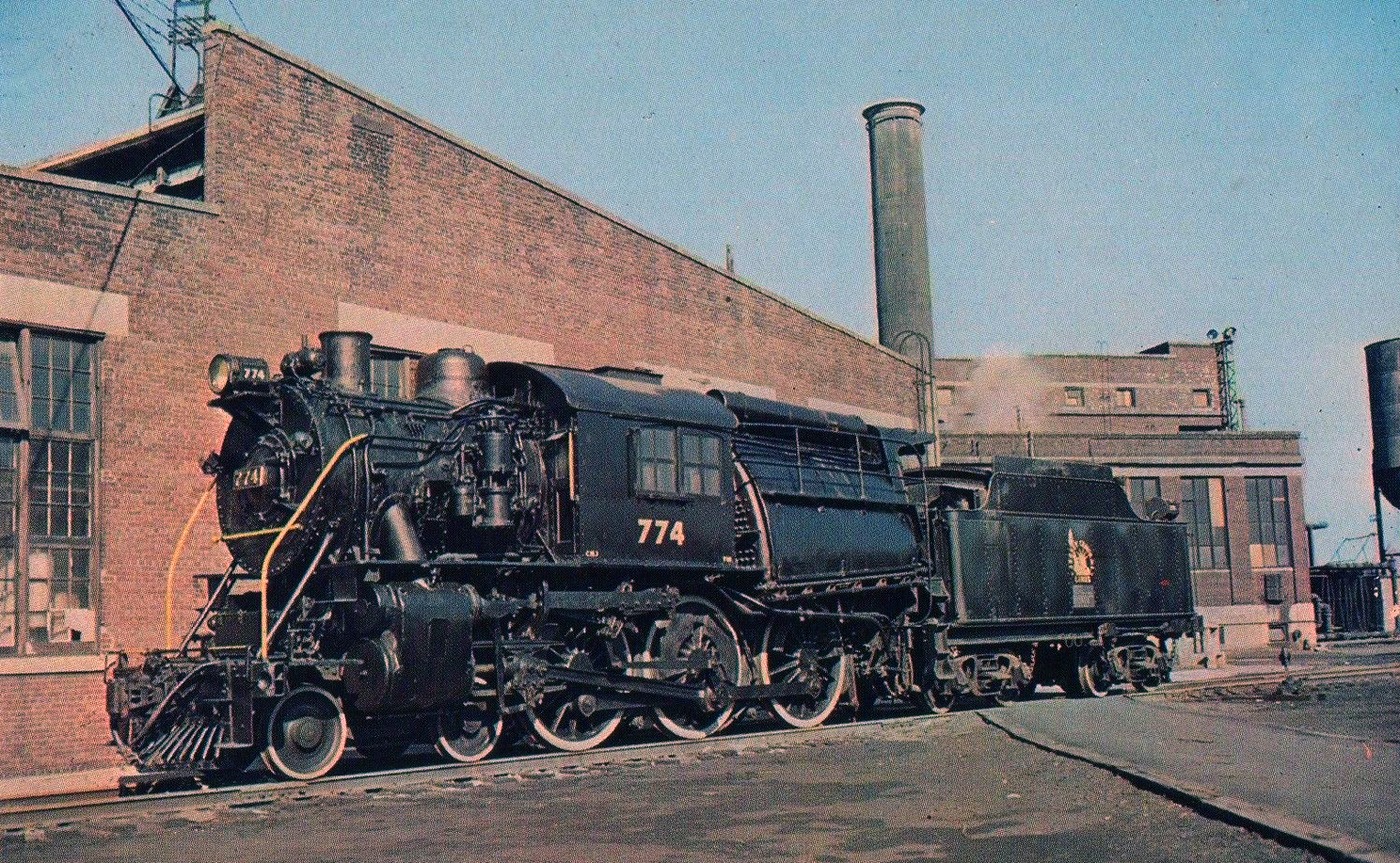

Jersey Central 4-6-0 #774 (Class L7as) with its massive Wootten Firebox is seen here at the engine terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey on March 2, 1956. Despite being all shined up, eight days later the "Camelback" was scrapped. Don Wood photo.

Jersey Central 4-6-0 #774 (Class L7as) with its massive Wootten Firebox is seen here at the engine terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey on March 2, 1956. Despite being all shined up, eight days later the "Camelback" was scrapped. Don Wood photo.The adoption and adaptation of the Camelback across various railroads illustrate its significant influence and utility in the realm of steam engines.

Notably, railroads such as the Lehigh & New England took innovative steps by converting existing locomotives with common wheel arrangements, such as the 2-8-0 Consolidations, into Camelbacks. This adaptation extended the utility and efficiency of their existing fleets.

A singular achievement in the history of Camelback was realized by the Erie with its exceptional 0-8-8-0 articulated design, classified as Class L-1.

This locomotive not only holds the distinction of being the largest Camelback ever constructed but also remains the only articulated such design ever developed, marking a significant milestone in locomotive engineering.

In total, the Camelback model saw nearly 3,000 examples produced, which included locomotives that were either custom-built, purchased directly from manufacturers, or ingeniously rebuilt from more conventional designs by individual railroads.

This prolific production and widespread adaptation underscore the Camelback's critical role in the evolution of steam locomotive technology during its era.

Delaware & Hudson 2-8-0 #810, a Camelback Consolidation sporting a huge Wootten firebox so common with this design, is seen here ahead of a short passenger consist at French Mountain, New York during the summer of 1946. Arthur Martin photo.

Delaware & Hudson 2-8-0 #810, a Camelback Consolidation sporting a huge Wootten firebox so common with this design, is seen here ahead of a short passenger consist at French Mountain, New York during the summer of 1946. Arthur Martin photo.Decline

The design of Camelback, while innovative, presented significant challenges and risks for train crews. Engineers, stationed in the cab above the boiler, often endured extremely uncomfortable and hot conditions, especially during warmer months.

Moreover, this positioning placed them at a higher risk of injury should any component of the driving wheel assembly fail while the train was in motion. Further complicating safety concerns, the fireman's position at the rear by the firebox left him exposed to the elements.

Reading 4-6-0 "Camelback" #590 is seen here with what appears to be a short passenger train at Camden, New Jersey on December 11, 1946.

Reading 4-6-0 "Camelback" #590 is seen here with what appears to be a short passenger train at Camden, New Jersey on December 11, 1946.This location was necessary for him to continuously feed fuel into the locomotive, but it significantly compromised his safety and comfort. Recognizing the inherent dangers posed by the Camelback, the Interstate Commerce Commission took decisive action.

1927 Ban (ICC)

After closely examining the risks to which train crews were exposed, the agency imposed a complete ban by 1927 on the production of new or rebuilt locomotives featuring the Camelback design. This regulatory intervention underscored a critical shift towards prioritizing safety in locomotive engineering and design.

Preserved examples of the Camelback design include those at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum and others, which highlight the unique engineering and historical significance of Camelback locomotives.

Today, the Camelback locomotive serves as a fascinating footnote in the history of railroad technology, representing both the innovative spirit of the age and the evolving standards that prioritize safety and efficiency in transportation design.

Their story is a testament to the complex balancing act between innovation, practicality, and safety, which continues to challenge and drive advancements in locomotive technology.

Preserved Camels

- Baltimore & Ohio 4-6-0 #173 at the Museum of Transportation (St. Louis)

- Baltimore & Ohio 4-6-0 #305 at the Baltimore & Ohio Museum (Baltimore)

Preserved Mother Hubbards

- Central Railroad of New Jersey 4-4-2 #592 at the Baltimore & Ohio Museum (Baltimore & Ohio)

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western 4-4-0 #952 at the National Transportation Museum (St. Louis)

- Reading 0-4-0 #1187 at the Age of Steam Roundhouse (Sugarcreek, Ohio)

Sources

- Morrison, Tom. American Steam Locomotive In The Twentieth Century. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019.

- Schiffer Publishing Company. Baldwin Locomotive Works: Record of Recent Construction Nos. 21 to 30 Inclusive. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, 2009.

- Simpson, Walter. Steam Locomotive Energy Story, The. New York: American University Presses, 2021.

- Solomon, Brian. Baldwin Locomotives. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2009.

- Solomon, Brian. Classic Locomotives, Steam And Diesel Power in 700 Photographs. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2013.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

New Jersey's ~Murder Mystery~ Dinner Train Rides

Oct 19, 25 09:20 AM

There are currently no murder mystery dinner trains available in New Jersey although until 2023 the Cape May Seashore Lines offered this event. Perhaps they will again soon! -

Indiana's ~Murder Mystery~ Dinner Train Rides

Oct 19, 25 09:12 AM

This piece explores the allure of murder mystery trains and why they are becoming a must-try experience for enthusiasts and casual travelers alike. -

Connecticut's ~Murder Mystery~ Dinner Train Rides

Oct 19, 25 12:05 AM

All aboard the intrigue express! One location in Connecticut typically offers a unique and thrilling experience for both locals and visitors alike, murder mystery trains.