- Home ›

- Landmarks ›

- Cajon Pass

Cajon Pass (Railroad Grade): Map, History, Accident

Last revised: August 24, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Cajon Pass (pronounced, "KA-HOAN," which means box in Spanish) is, indeed, a box canyon, located just northwest of San Bernardino, California and less than 65 miles from downtown Los Angeles. It is the result of the San Andreas Fault, which splits two mountain ranges, the San Bernardinos and San Gabriels.

In 1885 the California Southern Railroad opened the first usable and efficient transportation corridor through the region, which later became the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe's (AT&SF) main line. The project was spearheaded during the 1880's under AT&SF's most influential and important leader, William Barstow Strong.

He outmaneuvered Southern Pacific's Collis P. Huntington for access into the Golden State and eventually established service to all of its major cities.

Following its completion, Cajon Pass provided the Santa Fe with a through corridor to Los Angeles and San Diego, cities which would transform into major ports and commercial centers a century later.

Today, BNSF continues to utilize the pass, as does Union Pacific. For many years UP leased the Santa Fe line until predecessor Southern Pacific (acquired in 1996) completed the nearby Palmdale Cutoff in the 1960s.

At one time the route contained two tunnels (roughly 500 feet in length), since "daylighted" (removed) as part of improvements undertaken over the years to reduce curves and grades.

Photos

A long parade of Santa Fe GP30's, led by #1234, have an eastbound climbing the 2.2% grade around Sullivan's Curve during the late 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.

A long parade of Santa Fe GP30's, led by #1234, have an eastbound climbing the 2.2% grade around Sullivan's Curve during the late 1960s. American-Rails.com collection.History

What is now recognized as Cajon Pass was well-known by the region's Native American Indians, particularly the Serrano, long before Europeans arrived.

According to the article, "Cajon Pass: Where Trains Descend From Cactus To The Groves Of The Orange Empire" by Howard Eichstadt from the October, 1941 issue of Trains Magazine, the first modern Caucasian to discover this natural passageway was William Wolfskill in 1831 during his journey from Santa Fe to the small city of Los Angeles.

It later acted as part of the Mormons' Smith Trail, used to found the city of San Bernardino in 1851. The idea of a railroad through this region, of course, was still decades away.

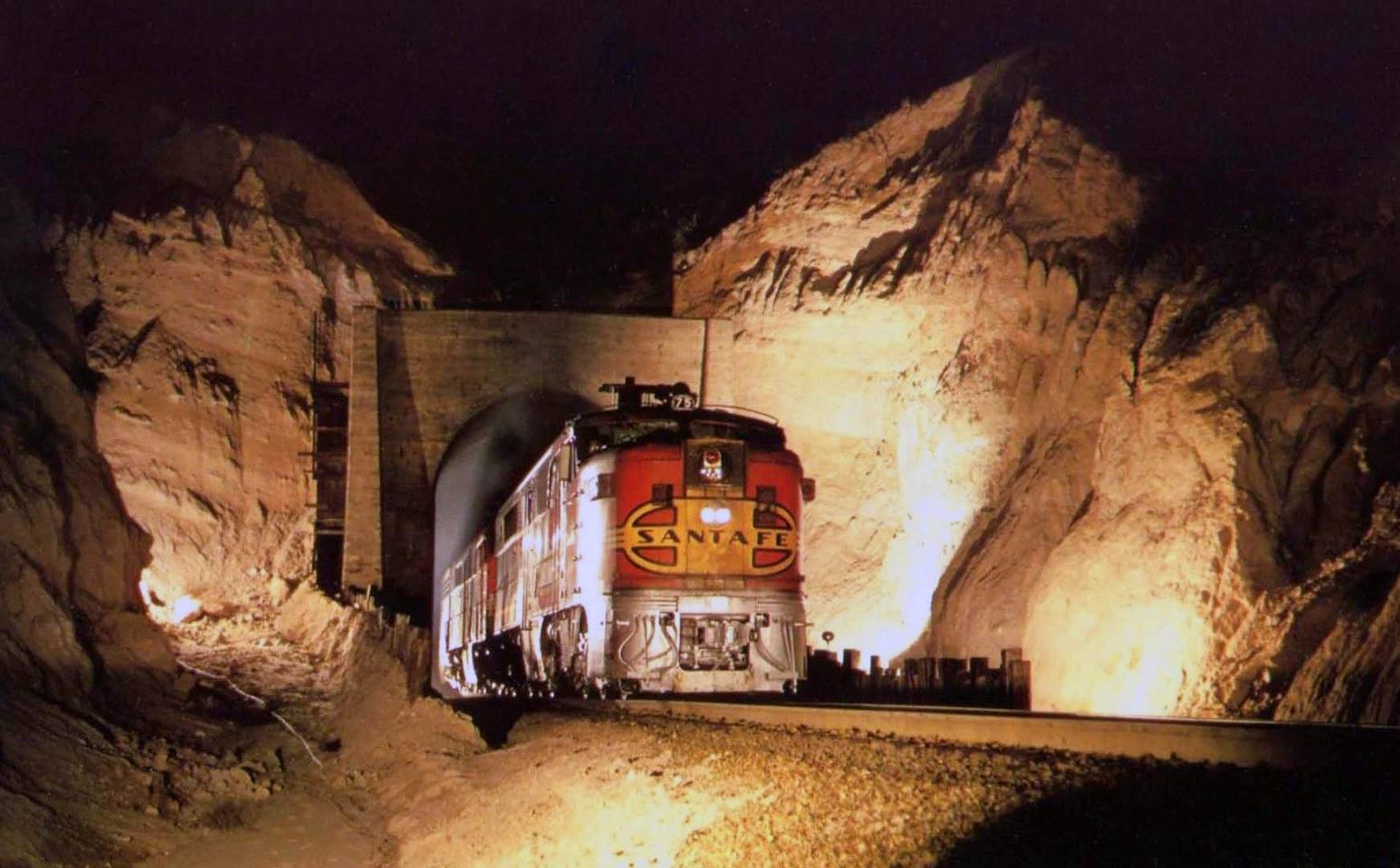

At around 2:30 a.m. on the morning of February 27, 1967, Santa Fe's train #8, the eastbound "Fast Mail Express," exits from one of the two tunnels (since daylighted) on Cajon Pass. The train had departed Los Angeles at around Midnight. William Mills photo.

At around 2:30 a.m. on the morning of February 27, 1967, Santa Fe's train #8, the eastbound "Fast Mail Express," exits from one of the two tunnels (since daylighted) on Cajon Pass. The train had departed Los Angeles at around Midnight. William Mills photo.That changed with the Transcontinental Railroad's completion in 1869 between Sacramento and Omaha, Nebraska. Our country's first corridor to the west coast was constructed along the federal government's so-called central routing, sponsored a decade earlier.

There were also northern and southern routes commissioned. The latter began as the Pacific Railroad (PR), chartered by the State of Missouri for the purpose of linking St. Louis with the Pacific coast.

According to Keith Bryant, Jr.'s excellent book, "History Of The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway," the PR would follow a route along the 35th parallel.

Atlantic & Pacific Railway

By 1853 this system had completed 38 miles but then quickly ran out of money. Following a series of name changes and failed expectations it became the Atlantic & Pacific Railway in 1870.

The A&P remained focused on the west coast although, despite its grandiose name, was primarily interested in a western route from Springfield only.

At the time the A&P was under General John Fremont's direction, an individual who was successful in securing about one million acres in federal land grants to see the southern leg completed.

By 1870 the railroad was operating a continuous 300 miles from Pacific, Missouri to Vinita, Indian Territory (later Oklahoma).

It had also surveyed a disconnected western segment between Isleta, New Mexico and Needles, California before financial struggles arose and the company slipped into bankruptcy once again on October 30, 1875. In 1876 it became the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway, with continued intentions of reaching the west coast.

Santa Fe GP35 #3454 and several other EMD's lead a string of empty hoppers eastbound over the summit of Cajon Pass in 1979. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.

Santa Fe GP35 #3454 and several other EMD's lead a string of empty hoppers eastbound over the summit of Cajon Pass in 1979. Mike Bledsoe photo. American-Rails.com collection.Santa Fe Involvement

Realizing the StL&SF's completion could seriously jeopardize its own transcontinental aspirations, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe became involved.

Under the direction of William Barstow Strong the AT&SF and StL&SF signed the "Tripartite Agreement" in 1879, which essentially gave the former control of the latter.

By August, 1883 the Santa Fe had completed its route to the California border at Needles but, due to the original A&P's charter, could only meet the Southern Pacific at that point.

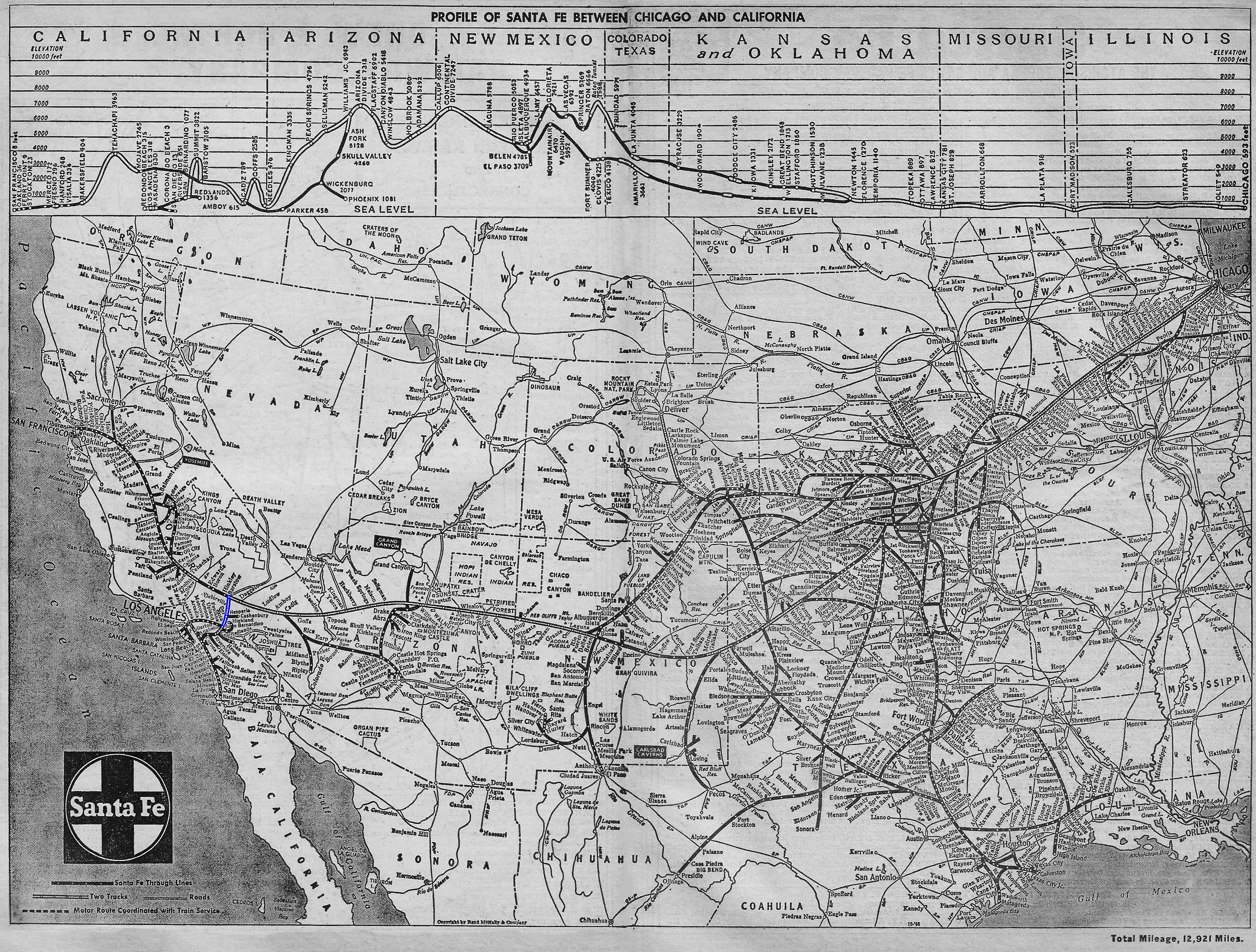

Map (1966)

In an effort to control a direct route to the Pacific coastline, Strong convinced Huntington to sell part of a Southern Pacific branch between Needles and Mojave to reach, among other locations, the fledgling ports of Los Angeles and San Diego.

As Mr. Bryant's book notes, the original Pacific Railroad's survey was carried out by Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple of the U.S. Army in 1853. He, and his party, worked west from Fort Smith, Arkansas, passing through West Texas and Albuquerque, New Mexico before arriving in Southern California.

On February 20, 1854 they arrived at "The Needles," so-named for a three-pronged rock formation on the California side of the Colorado River.

From this point they crossed the Mojave Desert and over Cajon Pass before arriving in Los Angeles on March 21st that year. While Strong worked on a permanent foothold in the Golden State, San Diego leaders lobbied hard for the Santa Fe to reach their town.

The AT&SF was eventually convinced and aided the California Southern Railroad in its endeavor to build north along the coast whereupon it would meet the Santa Fe pushing south towards San Bernardino. It is here where the story of a rail route through Cajon Pass begins.

Construction

The Colorado Southern Railroad was a project launched by one of San Diego's most prominent business leaders, Frank Kimball. In 1879 he owned the Rancho de la Nacional and went to great lengths in seeing a railroad reach San Diego.

During an initial trip to the east coast he was unsuccessful in convincing such magnates as Jay Gould or Tom Scott to undertake such an endeavor.

However, the Santa Fe showed much greater interest, lured in part by a 10,000-acre land grant, which the railroad believed offered incredible real estate potential.

After another trip to Boston, Massachusetts, Kimball and the city of San Diego successfully persuaded the AT&SF which agreed to underwrite a railroad running via San Bernardino.

The California Southern was incorporated on October 16, 1880, organized by Kidder, Peabody & Company, Thomas Nickerson, and three additional Santa Fe officers. They set a target date of July 1, 1882 to complete the 116 miles from San Diego to San Bernardino, which would meet the Santa Fe/A&P at the latter location.

In this Santa Fe publicity photo, a set of classic F units, led by F7A #252-C, climb the 2.25% grade over the newer alignment near the summit of Cajon Pass in April, 1964. Author's collection.

In this Santa Fe publicity photo, a set of classic F units, led by F7A #252-C, climb the 2.25% grade over the newer alignment near the summit of Cajon Pass in April, 1964. Author's collection.In the end, the California Southern received much more than originally agreed upon; this included 17,356 acres of land south of San Diego, two miles of property along the waterfront, 486 city lots for a depot and terminal, and finally $25,410 in cash.

With a capitalization set at $2.9 million, the CS unofficially began construction on October 11, 1880 when chief engineer Joseph Osgood set up headquarters in San Diego that day.

Since the railroad was provided a great deal of property from Kimball's National Ranch, it launched construction from National City (also the location of its primary shops), just south of San Diego.

By January 2, 1882 there were 55 miles completed to Fallbrook Junction and later that year, on August 16th, track crews arrive in Colton (just south of San Bernardino). Interestingly, despite numerous railroads either completed or under construction throughout the West at that time, materials for the California Southern project were purchased from overseas vendors, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and traversed dangerous Cape Horn before arriving in San Diego.

The first ship, a British-flagged vessel known as the Trafalgar, arrived with German and Belgian rails in March, 1881. After a drawn out fight with the Southern Pacific to cross its tracks in Colton, the CS opened service to San Bernardino on September 13th.

Completion

At this point, the railroad's future appeared uncertain; it ran out of money but still needed to reach the Santa Fe/A&P at Barstow. In addition, severe flooding through the Temecula Canyon (about halfway between San Diego and San Bernardino) during January and February of 1884 caused $319,879 in damages, money the CS did not have.

It resulted in the railroad's closure for nine months and to make matters worse, its landlocked status meant there was little business available. Realizing it may enter bankruptcy and fall into Southern Pacific's hands, Strong sought direct ownership of the property.

This endeavor coincided with his arrangement to purchase SP's Mojave-Needles lines. Through a stock and bond exchange, the AT&SF acquired control of the California Southern allowing for repair of the flood damage and completion of the unfinished 81-mile stretch from San Bernardino to Barstow (then known as Waterman).

Conquering Cajon Pass became the job of engineer Ray Morley and surveyor Fred Perris who, following the Santa Fe's takeover of the project, were tasked with finding a suitable rail route through this rugged landscape.

A pair of Union Pacific DDA40X "Centennials," led by #6926, along with SD40-2 #8030, work trailers westbound over Cajon Pass, just east of Keenbrook, California, circa 1976. American-Rails.com collection.

A pair of Union Pacific DDA40X "Centennials," led by #6926, along with SD40-2 #8030, work trailers westbound over Cajon Pass, just east of Keenbrook, California, circa 1976. American-Rails.com collection.Operation

It proved a difficult task but they were able to maintain a maximum grade of 3.4% for eastbound movements between Cajon and Summit, which sits at an elevation of 3,823 feet above sea level. The final spike was driven on November 15, 1885 while the first through passenger train from San Diego departed the following day.

As Richard Steinheimer notes in his article from the September, 1974 issue of Trains Magazine entitled "Cajon Pass Revisited," at the turn of the 20th century the Los Angeles, San Pedro & Salt Lake Railway (LASP&SL), a Union Pacific predecessor, was looking for a means through the mountains.

Instead of attempting its own expensive venture through the pass the LASP&SL gained trackage rights in 1905 for a period of 110 years. As a result, not only could one witness such famous trains as the Chief, Super Chief, and El Capitan but also Union Pacific's City of Los Angeles, Challenger, and Gold Coast.

One of Cajon's first noteworthy improvement projects occurred in 1913 when a second line was completed (boasting two tunnels), to help accommodate growing traffic levels.

San Bernardino Train Wreck

Cajon Pass gained national attention on the morning of May 12, 1989 when a westbound Southern Pacific freight, carrying 69 loads of trona (a raw mineral used to process sodium carbonate), lost control descending the grade, derailed, and smashed into a residential area of San Bernardino along Duffy Street destroying seven houses.

The four locomotives at the head end (SD45R #7549, SD45R #7551, SD40T-2 #8278, and SD45T-2 #9340) were destroyed as were all of the 69 hopper cars in the train. The two helper locomotives trailing, SD45R #7443 and SD40T-2 #8317, derailed and were later returned to service.

Sadly, the conductor and brakeman at the head-end (Everett Crown, conductor, age 35) and Allan Riess, (brakeman, age 43, who was located in the third locomotive) were killed. In addition, four residents were killed in their homes.

The cause of the derailment was determined to be a combination of human and mechanical error. Following a thorough investigation the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) discovered that one of the locomotive's on the head-end had inoperative dynamic brakes as did one of the rear helper units.

The engineer, Lawrence Hill, in helper assignment was aware this locomotive's brakes were not functioning properly but failed to relay this information to the head-end. Once he realized the train was exceeding its authorized speed, Hill applied emergency braking which deactivated the dynamic brakes.

This compounded the issue as air, alone, could not control the heavy freight train. It reached speeds of 110 mph before derailing at a 35 mph, super-elevated curve along Duffy Street in San Bernardino. The NTSB also discovered that clerks in Mojave had miscalculated the train's weight at 6,151 tons when in fact its weight was 8,900 tons.

This second line, located to the west and 2 miles longer, was not as steep with only a 2.2% maximum grade compared to the original's 3%.

The line continues to be modernized in contemporary times; in 1972 AT&SF completed a project to reduce curves from 10 to 4 degrees while successor BNSF Railway added 5.9 miles of triple tracking, completed in 2009.

For nearly 80 years, the Santa Fe maintained a monopoly over Cajon until Southern Pacific inaugurated its 78-mile, $22 million Palmdale Cutoff in 1967, operating the first train on July 11th that year when SD40 #8478 broke through a "Short Cut For Shippers" banner.

Throughout the Santa Fe era, Cajon was a testing ground; it convinced management that oil was a more practical fuel than coal for steam locomotives and saw rigorous trials of Electro-Motive's new FT diesel set. The AT&SF was a major buyer of this locomotive and future EMD products.

The FT's could use their innovative dynamic brakes to greatly reduce brake-shoe wear; this, coupled with the diesels' greater fuel savings, reduced AT&SF's annual costs by millions.

A pair of handsome Santa Fe PA-1's have a railfan special at the summit of Cajon Pass in early 1964. Roy Gabriel photo. Author's collection.

A pair of handsome Santa Fe PA-1's have a railfan special at the summit of Cajon Pass in early 1964. Roy Gabriel photo. Author's collection.During the steam era watching the iron horse tackle Cajon's grades was truly a sight to behold. One could witness all of Santa Fe's big power here such as 4-8-2's double-heading passenger consists like the Pacific Limited while 2-10-2 "Santa Fe's" and 2-10-10-2 "3000 Class" Mallets fought heavy freights over the pass, sometimes double-headed while others were cut in mid-train.

And of course, Union Pacific also featured big power here such as the 2-8-8-0 "Bull Moose" Consolidation Mallet and 4-6-6-4 Challengers.

And that wasn't all; even into the early diesel days the AT&SF's gorgeous 4-8-4's could still be seen assisting the silvery, sleek Super Chief through Sullivan's Curve, a location made famous by Herb Sullivan who captured several stunning photos thanks to its wide open vistas.

The sweeping curve also became the backdrop for a number of publicity scenes while artists such as John Winfield and Andrew Harmantas have immortalized the spot in oils. Into the diesel days interesting lash-ups could still be found with long strings of F units working freights and passenger trains over the grades.

Even American Locomotive's beautiful PA model would occasionally make an appearance. As for the Union Pacific's, its gargantuan models like the experimental DD35 and DDA40X ("Centennials") could also be found on Cajon.

Because of the route's steep grades it has been the scene of many runaways, the most famous of which occurred in May, 1989 when a Southern Pacific freight train lost control and hit a residential area of San Bernardino, killing two civilians as well as the engineer and conductor.

Today, with the breathtaking scenery, numerous daily trains, and tough work required to move freight over the pass it is a big attraction for those who like to watch and film trains.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In New Jersey

Apr 10, 25 09:40 PM

This guide highlights passenger train services currently available throughout the state of New Jersey. -

Rio Grande 4-6-6-4 Locomotives: Specs, Roster, Photos

Apr 10, 25 12:47 PM

The Rio Grande owned some large wheel arrangements, including the 4-6-6-4s. Interestingly, the railroad was never satisfied with these engines. -

Guide To Amtrak/Passenger Trains In Michigan

Apr 10, 25 12:06 PM

Michigan offers a variety of passenger train services, allowing travelers to discover the state's beauty and charm in a relaxed and comfortable manner. Learn more here.