- Home ›

- Freight Cars ›

- Boxcars

Boxcars: Once Railroading's Ubiquitous Rail Car

Last revised: August 29, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Railroad boxcars are perhaps not only the best-recognized pieces of equipment ever put into service but also one of the most identifiable symbols of the industry itself.

It has a history tracing back to the earliest years when railroads realized that some freight and lading needed at least a little protection from the outside elements and Mother Nature.

However, after the turn of the 20th century the car truly became an industry icon and remained so through the 1960s, used to haul about any and every type of non-bulk traffic moved by train.

Over time railroads realized, largely through complaints by shippers, that more specialized cars were needed to haul unique types of freight.

An Ahnapee & Western Railway 50-foot boxcar, and others, in service on Conrail at Bowers, Pennsylvania on June 24, 1978. American-Rails.com collection.

An Ahnapee & Western Railway 50-foot boxcar, and others, in service on Conrail at Bowers, Pennsylvania on June 24, 1978. American-Rails.com collection.This issue led to the development of the well car, autorack, refrigerator car, and several other specific designs.

Boxcars, however, still have their place in today's industry especially in carrying bulky items such as autoparts.

In addition, for railfans, always be on the lookout for historic "fallen flag" logos and liveries which still grace some cars even decades after a particular company has disappeared.

During the early years of the industry freight was hauled on simple flatcars or early gondolas, which were essentially flatcars with short sides to keep the lading from rolling or falling off in transit (or in the case of bulk materials, to keep them confined).

Operational practices at the time often followed those of England, birthplace of the railroad.

However, since the United States experienced much harsher and unpredictable weather than its neighbors across the Atlantic, especially during the winter months, flatcars became impractical to handle more sensitive freight which must be kept dry.

In Upstate New York was the burgeoning Mohawk & Hudson Railroad, the first chartered system in the United States which later became part of the New York Central, came up with the novel idea of covering its gondolas in 1833 since the railroad dealt with snow throughout much of the winter.

The M&H concept is often credited as being the first type of boxcar and the railroad went on to build a small fleet of the cars, which could be loaded from one end.

Eventually, the car was heightened, and lengthened for ever-larger loads. As Mike Schafer notes in his book, "Freight Train Cars," this development proved a major deviation from English design and was one in a series of differences that made American railroading unique.

By the latter part of the 1830s this new style of car was beginning to catch on across the rest of the industry as its versatility and value was realized.

While the M&H invented the boxcar the pioneering Baltimore & Ohio is given the nod for developing the first practical design. At 30 feet in length and 7 feet wide it featured side-doors and was capable of handling 10 tons of freight.

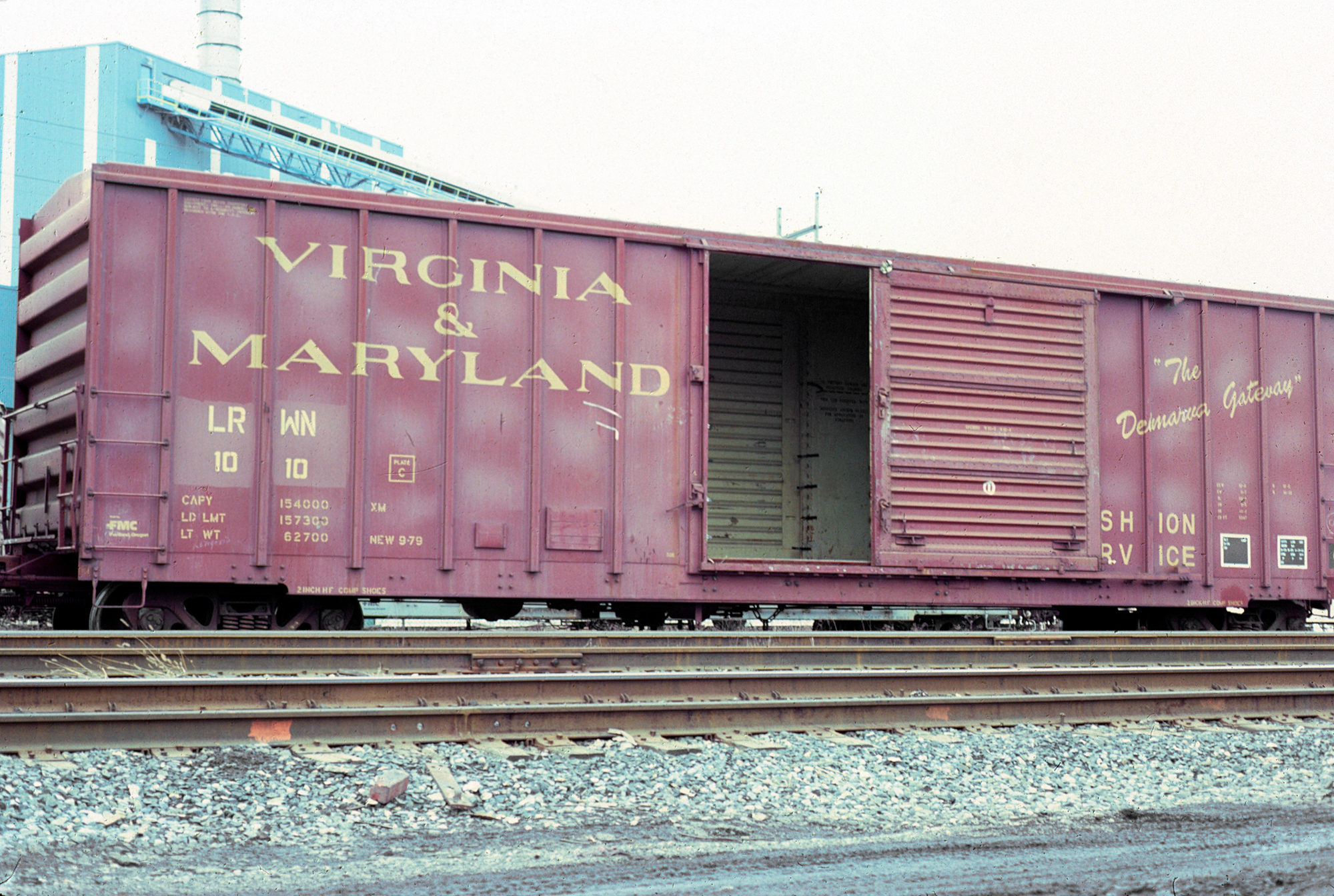

A Virginia & Maryland 50-foot boxcar, since sub-lettered for new owner Little Rock & Western, is seen here in March, 1983. The car was manufactured by the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) in 1979. American-Rails.com collection.

A Virginia & Maryland 50-foot boxcar, since sub-lettered for new owner Little Rock & Western, is seen here in March, 1983. The car was manufactured by the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) in 1979. American-Rails.com collection.The next major development occurred in 1870 when the industry adopted general interchange agreements, which allowed freight cars to roam outside of their home territory and onto other railroads.

This allowed for much more efficient operation and faster transit times. From this point on the boxcar only grew in size whereby at the end of the 19th century it was capable of 40-50 tons and expanded from 36-feet in length to the standard 40-foot car of the 20th century, which remained in widespread use well after World War II.

What made boxcars great, at least in the eyes of the railroads, was, their ability to haul about anything!

Railroads thrive on redundancy to maximize efficiency which was the reason they loved the boxcar so much (if it was not for shippers who requested many different specialized cars for their needs, railroads would have been happy to haul everything in boxcars).

A 50-foot boxcar, owned by the City of Prineville Railway (Oregon), is seen here in service during November of 1982. American-Rails.com collection.

A 50-foot boxcar, owned by the City of Prineville Railway (Oregon), is seen here in service during November of 1982. American-Rails.com collection.For instance, for many years the car carried everything from automobiles and paper to car parts and fresh produce; literally almost anything that would practically fit into the car’s empty, open spaces.

The car's development continued to improve over the years such as switching from basic wood construction, with steel outside-bracing, to all-steel designs for heavier loads.

This was achieved with the same size specifications; 40 feet was the standard size employed by the American Association of Railroads (AAR), although the initial standardization methods came about from the United States Railroad Association during WWI.

The first standard, all-steel design entered service in 1932 thanks to the recommendations of the American Railway Association, predecessor to the present-day AAR

While the 40-footer was a standard design it did come in different setups depending on the type of freight being transported.

For instance, double-doors became practical for large/wide loads, end-doors useful for very large lading such as automobiles, and interior tie-down equipment was helpful in keeping sensitive products from being damaged in-transit.

In 1954 the Santa Fe developed its "Shock Control" (and later "Super Shock Control") technology for new boxcars with upgraded suspension systems to further improve the ride-quality and reduce the chance of damaging freight.

The 50-foot boxcar made its first appearance in the 1930s and steadily grew in popularity over the years, which further improved redundancies by allowing for even more space within a given car. Today, the 50-footer remains the common boxcar size.

Although the boxcars of today no longer carry such varying amounts of cargo as they once did they remain an important freight car to the railroads.

And, while there are standard designs, these were not the only styles to ride the rails. During the 1960s the 89-foot "Hi-Cube" car was produced to carry large amounts of auto parts (which continues to see use today).

However, because of its length, traditional setup of four axles (two trucks), and designed to carry large, awkward-sized parts the car did not carry significant weight.

Finally, some railroads custom-built or designed their very own boxcars such as the Baltimore & Ohio's "Wagon Top": this design was developed by the railroad to save money brought on by the lean years of the Great Depression.

Its name came about because of its wagon-like appearance due to the outside bracing. There was also the Pennsylvania Railroad’s "Round Roof" design.

A recently delivered Boston & Maine 50-foot boxcar, built by Pullman-Standard, was photographed here in June, 1956. American-Rails.com collection.

A recently delivered Boston & Maine 50-foot boxcar, built by Pullman-Standard, was photographed here in June, 1956. American-Rails.com collection.In the Pennsylvania's particular case the car was meant to increase inside height dimensions for improved efficiency and it largely achieved the railroad's desired results.

The B&O’s design proved highly successful as well in both terms of providing it a reliable car to transport goods along with saving money by having its shop forces build the cars.

They could be found in service for many years and some of the caboose designs survived until the Chessie System era.

Not mentioned here are the other specialized boxcars that were developed to handle other specific types of freight such as the reefer for cold storage and stockcars to handle many kinds of livestock.

Recent Articles

-

Ohio Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:40 PM

This information highlights the currently active Class 3 short lines operating within the state of Ohio. -

Pennsylvania Short Line Railroads: A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:37 PM

Highlighted here is a complete list of active Class 3 short line railroads operating within the state of Pennsylvania. -

California Pumpkin Train Rides (2025): A Complete Guide

Mar 27, 25 12:25 PM

There is one location in California hosting the popular pumpkin train, at the Roaring Camp Railroads. Learn more about these event!