Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad: Map and History

Last revised: March 1, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The genesis of the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad (B&OCT), henceforth referred to in this piece, illuminates a compelling stage in the evolution of American railroad history.

The B&OCT found its dual origins in the efforts of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) to provide extensive terminal and switching services throughout Chicago, and in its strategic acquisition of several preceding railroads.

The prehistory of the B&OCT includes a rich roster of predecessor entities whose collective chronicles weave an intriguing narrative of growth, consolidation, and strategic market penetration.

Notable among these early formations were the Chicago Terminal Transfer Railroad Company and the La Salle & Chicago Railroad, among others, all of which eventually amalgamated into the expansive B&OCT.

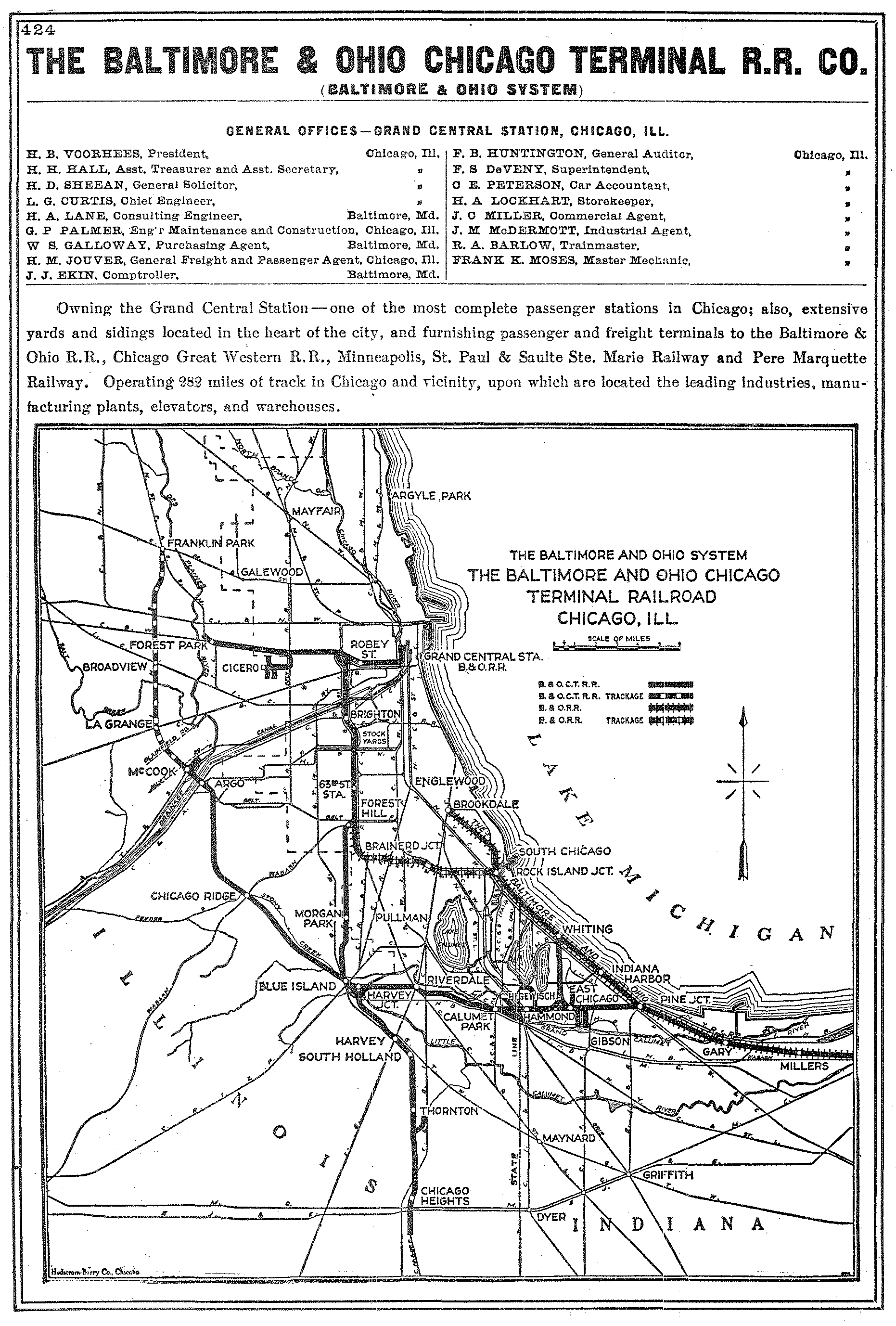

Steadfastly serving the greater Chicago area, the B&OCT ran a comprehensive network of routes that intricately spanned various city neighborhoods, suburban locales, and industrial sites. Its system formed a rough "L"-shape from Whiting, Indiana to Forest Park, Illinois.

Its reach extended to major regional transit hubs, freight yards, and passenger terminals, fostering critical connectivity across a diversified demographic and economic base.

Other notable terminal railroads serving the industry's most important hub included the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern; Indiana Harbor Belt; and Chicago & Western Indiana. Today, the B&OCT carries on as part of CSX Transportation.

Photos

Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal 0-8-0 #1704 appears to be carrying out switching chores at the Lincoln Street Coach Yard on March 25, 1956.

Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal 0-8-0 #1704 appears to be carrying out switching chores at the Lincoln Street Coach Yard on March 25, 1956.History

In their book, "Baltimore & Ohio Railroad," authors Kirk Reynolds and David Oroszi note the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal's earliest predecessor was the La Salle & Chicago Railroad, formed in 1867.

Its charter was later acquired by the Chicago & Great Western (C&GW). In 1885 this system had opened a line from Forest Park, in the city's northwestern region, into downtown Chicago with its primary passenger terminal located along Polk Street.

The C&GW was then a terminal system for the Wisconsin Central and Minnesota & North Western, the former a subsidiary of the Soo Line and the latter the Chicago Great Western.

At this time, the growing Northern Pacific, then owned by Henry Villard, acquired the Wisconsin Central to provide the transcontinental carrier direct access into the Windy City. The NP formed the Chicago & Northern Pacific (C&NP) in 1890 to operate the C&GW.

Villard, believing the NP's Chicago connection was secure, constructed the beautiful Grand Central Station. Located at 201 West Harrison Street, the facility was designed by architect Solon Spencer Beman in the style of a Norman castle.

The building's overall dimensions were 228 feet wide and 482 feet long with more than 110,000 square feet of interior space.

However, the station's most impressive feature was its beautiful 247-foot clock tower whose magnificent timepiece kept accurate time through the end and at during its early years featured a bell, which rang on each hour.

It opened on December 8, 1890, the second-oldest second-generation passenger terminal in Chicago (the oldest being Dearborn Station constructed in 1883).

In the late 19th century the Baltimore & Ohio was still attempting to find a permanent Chicago home, having first arrived in the city in 1875. The B&O first began using Grand Central in 1891 via trackage rights over the Rock Island and Pennsylvania between South Chicago and Western Avenue.

At A Glance

As traffic became more congested throughout the city, the B&O negotiated trackage rights via the Chicago & Calumet Terminal (C&CT) during this same period. It was also owned by Villard and operated from Whiting, Indiana (where a connection was made with the B&O) to McCook, Illinois (where it interchanged with the Santa Fe).

The C&CT eventually reached Franklin Park via a line operated in conjunction with the Chicago, Hammond & Western (predecessor to the Indiana Harbor Belt). Together, these systems jointly operated trackage from Blue Island to Franklin Park.

At the latter point a connection was established with the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (Milwaukee Road). In 1890 the C&NP acquired the Chicago Central Railway, which operated a line from downtown Chicago to Blue Island, thereby establishing a connection with the C&CT.

The financial panic of 1893 forced Villard to divest both the C&NP and Wisconsin Central (which was later purchased by the Soo Line). The former was reorganized as the Chicago Terminal Transfer Railroad (CTT) in 1897 and subsequently reacquired the C&CT.

In 1898 the C&CT continued to grow by completing a southerly line from Blue Island to Chicago Heights, connecting there with the Michigan Central/New York Central and Elgin, Joliet & Eastern.

By the early 1900s the CTT, itself, was in bankruptcy. The B&O, having leased Grand Central Station in 1900, saw a great benefit in having its own Chicago terminal system. On January 6, 1910 it formed the Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad, a wholly-owned subsidiary, to acquire the CTT operation.

The roughly "L" shaped system contained, at its peak (1920s), 365 track mileage (which comprised both the mainline and the extensive array of sidings) and 78 route miles.

In addition, it maintained 42 miles of trackage rights and connected with 34 different railroads at 54 different points, handling, on average, 3,500 carloads daily. Nearly half of this figure was handled for the B&O itself.

The creation of the B&OCT followed a strategic decision by the B&O to consolidate its operations in the Chicago area to optimize operational performance and market penetration.

The B&OCT's primary main line ran 34 miles from NE Tower at Pine Junction to Grand Central Station. It also connected Bellwood, Forest Hill, South Chicago, East Chicago, Calumet Park, Whiting, and Pine Junction. The B&OCT offered its parent direct access to its Grand Central Station along Chicago's North Side.

The B&OCT's chief function, of course, centered on switching services. As a subsidiary of the B&O, the terminal line facilitated the efficient movement of passenger and freight rail cars, offering both short and long-haul switching services, in addition to maintaining a strategic presence in the region.

Grand Central Station

The B&OCT's relationship with Chicago's Grand Central Station formed the vertebrae of its operational framework.

The company not only owned and operated the magnificent edifice of Grand Central Station, but it also used the pivotal structure as the operational hub of its wide-ranging switching and freight services.

In addition to massive freight operations, the B&OCT played a vital role in managing passenger services for the B&O within Chicago.

It dealt with the efficient movement of passenger rail cars to and from Grand Central, ensuring seamless connections with wider inter-city and suburban transit networks.

Barr Yard

The B&OCT's largest freight terminal was Barr Yard. In 1948, following a three-year expansion project, the facility's receiving yard could handle 345 eastbound and 500 westbound cars while the main classification yard held a capacity of 1,144 eastbound and 1,209 westbound cars.

Barr Yard also contained locomotive servicing facilities, including a turntable, roundhouse, RIP (repair-in-place) tracks, and a stockcar servicing yard. Parent B&O also used Barr as its primary maintenance facility for road locomotives operating into, and out of, Chicago.

System Map (1910)

Besides its own operations, the tracks of the B&OCT were utilized by several other railroads. Notable among these were the Pere Marquette Railway, Chicago Great Western, and the Wisconsin Central/Soo Line which all accessed the Grand Central Station via B&OCT's well-laid tracks. The facility was also later used by parent Chesapeake & Ohio.

The multi-faceted operation of the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal spanned a range of services.

The augmenting passenger services apart, the core function of the B&OCT manifested as the pivotal role it played in hauling freight across the Chicago area. It managed an expansive roster of freight types, ranging from industrial goods, raw materials to commercial merchandise.

The narrative of the B&OCT is intricately woven with the economic and industrial development of Chicago. The railroad facilitated the movement of raw materials and finished goods across the city, thereby contributing significantly to the industrial growth of Chicago and surrounding regions.

Over the course of the 20th century, the operations and services of the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad underwent several transformative phases, mirroring the larger technological and management trends within the railroad industry.

The B&OCT was not averse to adapting to the demands of changing times, successfully retaining its operational relevance throughout these transitions.

A critical transition in the history of the B&OCT emerged in the late 20th-century when it became a subsidiary of CSX Transportation in 1987, following the dissolution of the B&O. This strategic shift opened a new chapter in the railroad's continuing evolution, aligning it with one of the United States' largest transportation companies.

Diesel Roster

All units lettered for the B&OCT and painted in the B&O's standard blue dip livery with gold lettering. Standard B&O GP units, and switchers, also worked alongside these switchers.

In 1982, GP15Ts lettered for the Chesapeake & Ohio/Chessie System largely supplanted these early switchers.

| Model Type | Road Number (1st) | Road Number (2nd) | Road Number (3rd) | Serial Number(s) | Order Number | Date Built | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW1 | 217, 216, 218-221 | - | 8416-8421 | 1601-1606 | E462 | 5/1940-8/1940 | 6 | Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal |

| NW2 | 409-411 | - | 9509-9511 | 1729-1731 | E463 | 1/1943 | 3 | Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal |

| SW9 | 590-597 | - | 9600-9607 | 15886-15893 | 6366 | 2/1952-4/1952 | 8 | Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal |

CSX Transportation

Today, over a century since its inception, the legacy of the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad continues to resonate within the labyrinth of rail tracks that crisscross the Chicago region. Much of the original B&OCT routes continue to be an active part of the CSX Transportation network.

Despite the passage of time and changes in ownership, the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad's imprints within the American railroad landscape haven't faded.

Its operational architecture, characterized by an efficient network of rail tracks, switching yards, and the iconic Grand Central Station, remains a testament to its enduring legacy.

Sources

- Reynolds, Kirk and Oroszi, David. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2000.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Welsh, Joe. Baltimore & Ohio's Capitol Limited And National Limited. St. Paul: MBI Publishing, 2007.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Florida - Wine Tasting - Train Rides

Dec 22, 25 11:47 AM

Wine by train not only showcases the beauty of Florida's lesser-known regions but also celebrate the growing importance of local wineries and vineyards. -

Iowa Thomas The Train Rides

Dec 22, 25 10:50 AM

This article explores the magical journey of spending a day with Thomas and what families can expect from this unforgettable experience in Iowa. -

North Carolina Thomas The Train Rides

Dec 22, 25 10:45 AM

North Carolina is one of the few states home to two different Thomas the Tank Engine events. Learn more about them here!