Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal Railroad: Map, History, Roster

Last revised: January 31, 2025

By: Adam Burns

The Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT) represents a significant chapter in the history of New York's industrial and transportation sectors.

Founded in the late 19th century, the BEDT played a crucial role in linking waterborne freight with the industrial heart of Brooklyn and beyond.

The terminal road might not have been vast, operating just 11 total miles of track at its peak. However, it distinguished itself with a substantial fleet of locomotives and a commitment to steam power, which lasted until 1963.

Among the four independent rail-marine terminals in Brooklyn, which included Bush Terminal Company, Jay Street Terminal (Jay Street Connecting Railroad), and New York Dock Railway, the BEDT stood out as the largest.

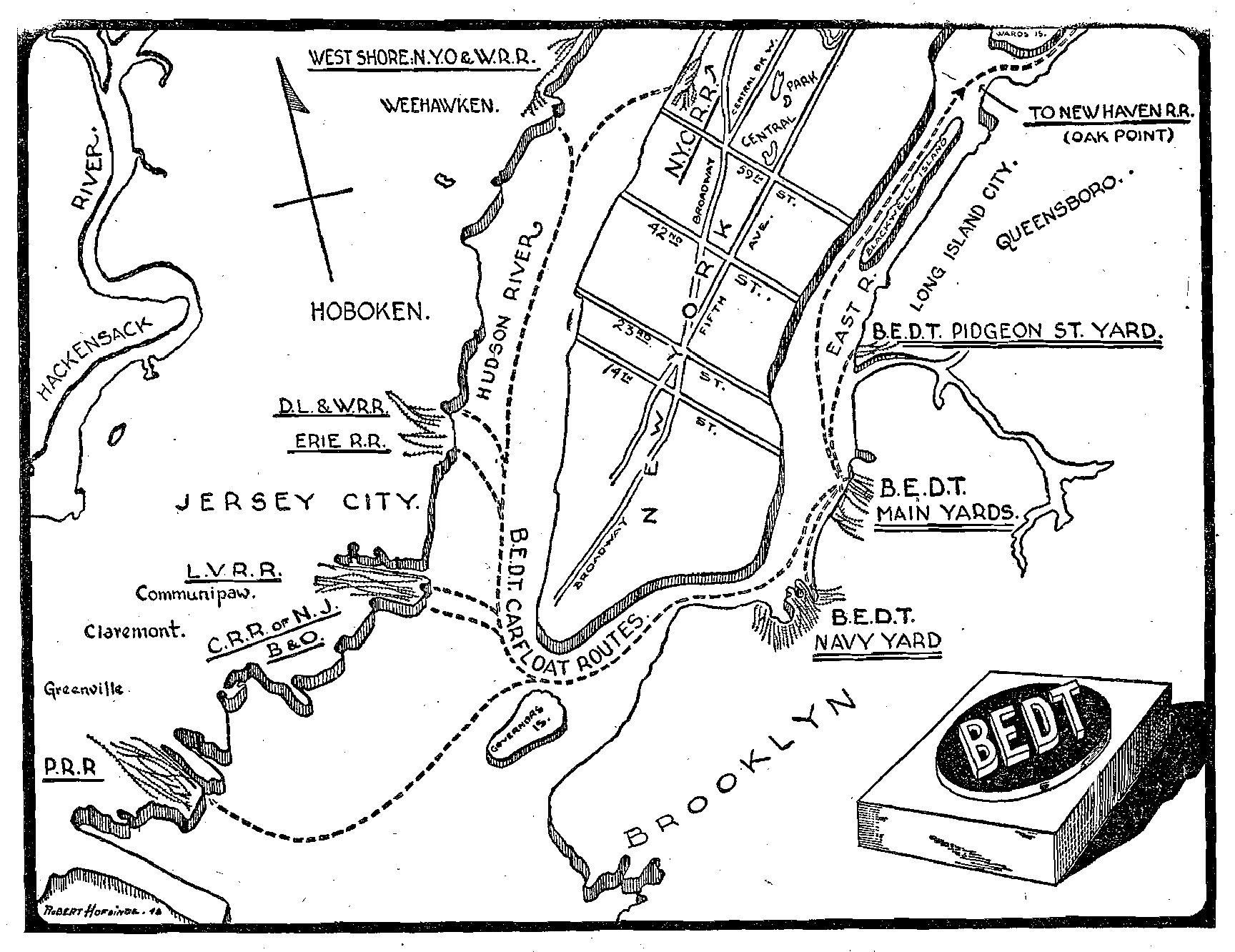

Throughout its operational history, the system managed at least six car float bridges strategically positioned along the Brooklyn waterfront at North 3rd Street, North 5th Street, North 6th Street, North 9th Street, Wallabout Market (from 1935 to 1941), and the Brooklyn Navy Yard (post-1941).

Beyond Brooklyn, the company maintained a float bridge in Queens at Pidgeon Street and one in New Jersey at Warren Street (from 1910 to approximately 1929).

Additionally, there was a pier station at Queensboro Terminal in Queens, located at 14th Street in Long Island City, near the Long Island Rail Road's Long Island City station. Wallabout Market, which opened around 1933, eventually integrated with the Navy Yard operations in 1941. The Queensboro Terminal opened its doors in 1914 and remained in service until around 1930.

The BEDT earned its place in the annals of history as the final operator of steam locomotives for freight service in New York, with steam operations drawing to a close on October 25, 1963.

The terminal continued its operations with diesel locomotives until its closure in 1983. This enduring legacy reflects both its historical significance and contributions to the region's transportation landscape.

This article seeks to provide a comprehensive history of the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal, detailing its origins, operations, and eventual decline, while emphasizing its lasting impact on the region's economic and urban landscape.

Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal S1 #24 along the East River waterfront in Brooklyn, New York; December, 1976. American-Rails.com collection.

Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal S1 #24 along the East River waterfront in Brooklyn, New York; December, 1976. American-Rails.com collection.Beginnings and Development

The BEDT's origins can be traced back to the growing need for efficient freight handling and transportation in New York City. In the late 19th century, Brooklyn emerged as a critical industrial hub, housing numerous factories, warehouses, and manufacturing plants.

The demand for an efficient system to move goods between these facilities and the waterfront, where barges and ships docked, prompted the creation of a specialized terminal.

BEDT was established under the leadership of the principals of Havemeyers & Elder, particularly Henry O. Havemeyer (1847–1907). It succeeded Palmer's Docks, an earlier marine and rail operation founded by Lowell Mason Palmer (1845–1915).

In 1875, Palmer partnered with the Havemeyers to extend the scope of Palmer's Docks, an expansion that continued until 1905. Upon Palmer's departure in 1906, the Havemeyers restructured the organization, incorporating it as the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal, a navigation corporation.

The rail operations were separately incorporated as the East River Terminal Railroad in 1907. By 1915, the two entities were merged into a unified Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal as a freight terminal corporation.

The Havemeyer family, renowned for their prominence in the sugar refining industry with their enterprises "Havemeyer & Elder Sugar Refining" and later "American Sugar Refining," operated separately from the BEDT.

The sugar refiners, later associated with Domino Foods, Inc., maintained their independence from the rail and maritime operations due to ongoing legal issues in the sugar industry.

Despite its separation, the Havemeyer family remained directly involved in the administration of the BEDT until 1972. Subsequently, the BEDT underwent several ownership changes, being acquired by Petro Oil from 1972 to 1976, R.J. Reynolds from 1976 to 1978, and finally New York Dock Properties from 1978 until 1983.

Thus, the BEDT's storied history reflects a dynamic evolution under the stewardship of industrial pioneers and various corporate entities.

Operational Dynamics

The BEDT's primary operation involved the transfer of freight between maritime vessels and rail cars.

This process, known as "lighterage," involved using small vessels called lighters to shuttle cargo from larger ships anchored in the river to the terminal. The cargo was then loaded onto railcars that traveled across the rail network serving Brooklyn's industrial districts.

One of the BEDT's most distinguishing features was its fleet of tugboats and barges, which played a crucial role in its operations.

These vessels were responsible for navigating the busy waters of New York Harbor, bringing in raw materials like coal, lumber, and chemicals while exporting finished goods produced in Brooklyn's factories.

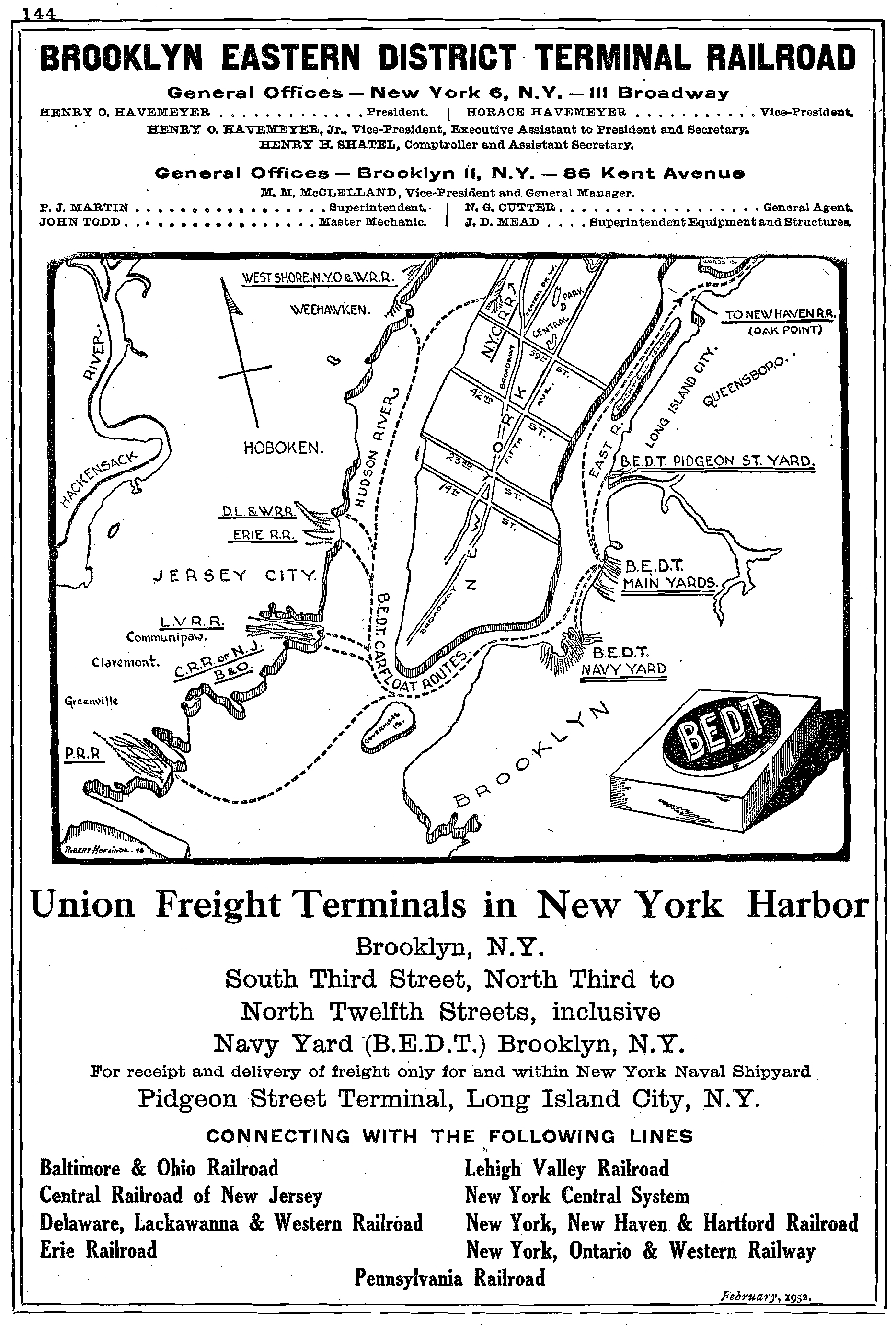

The terminal's rail network connected to several major railroads, including the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, Jersey Central, Lackawanna, Erie, Lehigh Valley, New York Central, New Haven, and New York, Ontario & Western.

This intricate web of connections facilitated the smooth movement of goods, ensuring that Brooklyn's industries had a steady supply of raw materials and an efficient means to distribute their products.

Technological Adaptations

Throughout its history, the BEDT consistently adapted to technological advancements in the transportation and logistics sectors. The transition from horse-drawn wagons to motorized trucks, for example, significantly impacted how goods were moved to and from the terminal.

The introduction of diesel-powered tugboats and more efficient cargo-handling equipment further enhanced the terminal's operational capacity.

Another notable technological adaptation was the incorporation of floating grain elevators. These floating structures were essentially large barges equipped with machinery to transfer grain from ships to railcars or storage bins.

This innovation was crucial for the grain trade and underscored the BEDT's ability to evolve in response to changing industrial demands.

World War II and Peak Operations

World War II marked a period of immense activity for the BEDT. New York City's strategic importance as a manufacturing and shipping hub meant that the movement of war materials and supplies became a top priority. The BEDT's role in facilitating the seamless transfer of these goods earned it a vital place in the war effort.

During this time, the terminal saw peak operations, with freight volumes reaching unprecedented levels. The workforce swelled, and the infrastructure was pushed to its limits as loading and unloading cargo became a round-the-clock endeavor.

The war-induced boom not only underscored the BEDT's importance but also injected significant economic energy into the surrounding communities.

System Map (1952)

From the 1930s through the late 1950s, the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT) enjoyed a period of sustained prosperity. In 1941, the condemnation of Wallabout Market for the expansion of the Brooklyn Navy Yard led to the BEDT securing a pivotal government contract to manage the Navy Yard's trackage.

This task involved transporting essential supplies from the mainland U.S. to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, including steel for shipbuilding, coal for forges and power plants, and forged naval rifles for warships, among many other critical items.

As World War II intensified, rail traffic to the Navy Yard surged significantly. Additionally, the BEDT played a crucial role in transporting vast quantities of meat for the Cudahy, Morrell, and Armour meat packers based in Brooklyn, ensuring a steady supply of provisions.

The transition from steam to diesel-electric locomotives marked another significant development for the BEDT. The last steam locomotive ran on October 25, 1963, ushering in a new era of diesel-electric operations.

In 1964, the BEDT further expanded its capabilities by constructing the "Bulk Four Terminal" on Kent Avenue between North 8th and North 9th Streets.

This facility centralized the receipt and distribution of flour and semolina, essential for Brooklyn's commercial bakers and pasta manufacturers.

The BEDT also acquired the former PRR's North 4th Street Terminal properties, leasing the site to a scrap iron salvage company and handling the transportation needs for that operation.

The landscape of rail transport shifted dramatically in 1976 with the formation of Conrail by the U.S. government. This step was taken in response to the bankruptcy filings of several Northeast Class 1 railroads, including Penn Central, NYNH & Hartford, and Erie Lackawanna.

Conrail opted not to maintain the marine operations of these former railroads. Nonetheless, the necessity for carfloating operations to support Brooklyn's rail traffic was still recognized.

Consequently, Conrail solicited bids for a contract to continue these essential carfloating services, ensuring the continued movement of freight into Brooklyn.

Post-War Challenges and Decline

The post-war years brought a set of challenges that gradually eroded the BEDT's dominance. Several factors contributed to its decline, beginning with the rise of the trucking industry.

The proliferation of the interstate highway system and advances in truck technology made road transportation increasingly competitive, siphoning off some of the BEDT's traditional freight business.

Additionally, the advent of containerization revolutionized cargo handling. Containers allowed for more efficient and streamlined transfer of goods between ships, trains, and trucks, reducing the labor-intensive processes that were a hallmark of the BEDT's operations.

Major shipping companies began to favor containerized shipping, impacting traditional lighterage operations.

Brooklyn's industrial landscape also underwent fundamental changes. Many factories relocated or closed down, driven by factors such as urban development pressures, changing economic trends, and the suburbanization of industry.

The reduced industrial activity in the terminal's catchment area meant fewer goods required transfer, further diminishing the BEDT's role.

Dissolution and Legacy

The cumulative effect of these challenges led to the gradual dissolution of the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal. By the late 1970s, its operations had become increasingly limited, and many of its facilities were in decline.

In July 1975, the United States Railway Association unveiled its Final System Plan in alignment with the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973. This plan aimed to streamline the operations of railroads in the Northeastern United States.

The Interstate Commerce Commission subsequently recommended merging the operations of New York Dock Railway (NYD) and the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT) to eliminate redundancies.

By 1976, BEDT and NYD were the last remaining car-float operators in New York City. Conrail, formed from multiple bankrupt Northeast railroads, solicited bids for the carfloating contract to continue servicing Brooklyn-bound rail traffic.

BEDT emerged as the winning bidder and subsequently entered into a lease agreement with Conrail, granting them use of the former Pennsylvania Railroad’s Greenville Yard and adjacent floatbridge facilities. This allowed BEDT to continue managing Brooklyn-bound rail traffic through carfloating.

Around 1977, New York Dock Properties, the parent company of NYD, acquired the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal. This acquisition led to the merger of BEDT and NYD operations as recommended by the Final System Plan, though both entities retained their individual logos and equipment.

During this period, some older and less efficient equipment was retired or used for parts. The BEDT’s Pidgeon Street facility was closed around 1977–1978. By August 1983, the combined operations of BEDT and NYD ceased entirely, and their assets were acquired by New York Cross Harbor Railroad.

Following the cessation of operations in 1983, the BEDT property on Kent Avenue became abandoned and quickly fell into disrepair, becoming a haven for graffiti artists and squatters.

One of BEDT's historic steam locomotives, No. 16, remained on the property until it was rescued by the Railroad Museum of Long Island in 1996.

Today, the site of the former terminal has been transformed into East River State Park, with a short segment of track still visible in a concrete pad where the flour terminal building once stood. This transformation reflects the evolving urban landscape and serves as a historical reminder of Brooklyn's industrial past.

Despite its closure, the legacy of the BEDT persists in several ways. Its physical remnants, such as the piers, warehouses, and rail tracks, stand as historical markers of Brooklyn's industrial past. Some of these structures have been repurposed for modern use, attesting to the adaptability and resilience of urban landscapes.

Moreover, the BEDT's historical narrative offers insights into industrial and transportation evolution in New York City. Its story encapsulates themes of technological innovation, economic adaptation, and the dynamic interplay between industry and urban development.

The terminal's rise and fall mirror broader trends in American industry and transportation, making its history a valuable case study for scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Revitalization and Adaptive Reuse

In the years following the BEDT's closure, Brooklyn underwent significant transformations driven by urban renewal and gentrification.

Former industrial areas, including those once served by the terminal, witnessed a wave of redevelopment as new residential, commercial, and cultural spaces emerged.

Adaptive reuse of the terminal's buildings and infrastructure has played a crucial role in Brooklyn’s revitalization. The preserved structures have been repurposed for various uses, from commercial spaces and art galleries to office complexes and recreational areas.

These adaptive reuse projects not only honor the historical significance of the BEDT but also contribute to the contemporary urban fabric of Brooklyn. The waterfront areas that the BEDT once served have been transformed into attractive and economically vibrant zones.

The Williamsburg waterfront, for example, is now a hotspot for real estate development, featuring residential buildings with stunning views of the Manhattan skyline, parks, and cultural institutions. These transformations illustrate how historical industrial spaces can be successfully integrated into modern urban life.

Historical Documentation and Public Awareness

Efforts to document and preserve the history of the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal have been undertaken by historians, urban researchers, and rail enthusiasts.

Organizations like the New York Transit Museum and various historical societies have played a significant role in showcasing the terminal's contributions to Brooklyn’s industrial past.

Public awareness campaigns and educational initiatives have furthered the understanding of the BEDT's importance. Walking tours, exhibits, and publications provide residents and visitors with insights into how the terminal shaped the economic and social landscape of Brooklyn.

These efforts ensure that the terminal's legacy is not forgotten and highlights its role in the broader narrative of New York City’s development.

The BEDT also has a dedicated following among rail enthusiasts, who meticulously document its history and preserve artifacts related to its operations.

These enthusiasts maintain extensive archives, including photographs, timetables, and operational records, which offer invaluable resources for research and education.

Steam Roster

| Number/Name | Wheel Arrangement | Builder | Serial Number | Completion Date | Retirement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 "Frederick C. Havemeyer" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 3801 | 12/1875 | prior to 1933 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built to 6 foot gauge for Havenmeyer & Elder, later regauged for Palmer's Dock by Baldwin. |

| 2 "Florence" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 7596 | 5/1885 | Circa 1933 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #2. |

| 3 "Grace" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 8746 | 9/1887 | Circa 1933 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #3. |

| 4 "Lily" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 11439 | 12/1890 | Circa 1933 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #4. |

| 5 "Arthur" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 11982 | 6/1892 | Circa 1933 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #5. |

| 6 "Ethel" | 0-4-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 14743 | 3/1896 | Circa 1936 | Baldwin class 4-28-C (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #6. |

| 7 "Chester" | 0-6-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 17890 | 2/21/1900 | Circa 1936 | Baldwin class 6-32-D (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Comapny #7. |

| 8 "Carleton" | 0-6-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 18145 | 9/1900 | Circa 1936 | Baldwin class 6-32-D (steam dummy). Originally built for Lowell M. Palmer & Company #8. |

| 9 | 0-6-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 29543 | 11/1906 | Circa 1936 | Baldwin class 6-32-D (steam dummy). Originally built as Havemeyer & Elder & Company #9. |

| 10 | 0-6-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 39696 | 4/1913 | 1963 | Baldwin class 6-32-D. Scrapped 1963. |

| 11 | 0-6-0T | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 55276 | 2/1922 | 7/1962 | Baldwin class 6-32-D. Scrapped 1962. |

| 12 | 0-6-0T | H.K. Porter & Company | 6368 | 3/1919 | 6/1963 | H.K. Porter class 12-24-C-SS-I. Ex-United States Navy Fleet Supply Base - South Brooklyn Section #3. Preserved at the Florida Railroad Museum. |

| 13 | 0-6-0T | H.K. Porter & Company | 6369 | 3/1919 | 10/1963 | H.K. Porter class 18-24-C-SS-I. Ex-United States Navy Fleet Supply Base - South Brooklyn Section #4. Preserved at the Age of Steam Roundhouse. |

| 14 | 0-6-0ST | H.K. Porter & Company | 6260 | 9/1920 | 12/25/1963 | H.K. Porter class 18-24-C-S-I. Ex-Mesta Machine Works #5. Currently owned by the Ulster and Delaware Railroad Historical Society. |

| 15 | 0-6-0ST | H.K. Porter & Company | 5966 | 3/1917 | 12/25/1963 | H.K. Porter class 18-24-C-S-I. Ex-Mesta Machine Works. Acquired by the Strasburg Rail Road in 1998 and rebuilt into a Thomas the Tank Engine replica. |

| 16 | 0-6-0T | H.K. Porter & Company | 6780 | 1/1923 | 12/25/1963 | H.K. Porter class 12-24-C-S-I. Ex-Astoria Light, Heat and Power Company #5. Preserved at the Railroad Museum of Long Island.. |

Diesel Roster

| Number | Model | Builder | Serial Number | Completion Date | Heritage | Date Acquired | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | S1 | Alco | 75351 | 8/1947 | Union Railroad #453 | 1962 | Retired on 8/12/1983. Operated for a time on the New York Cross Harbor Railroad #21. Scrapped in 2006. |

| 22 | S1 | Alco | 75525 | 10/1947 | New Orleans & Lower Coast (Missouri Pacific) #9013 | 1962 | Retired on 8/17/1983. Operated for a time on the New York Cross Harbor Railroad #22. Scrapped in 2006. |

| 23 | S1 | Alco | 75526 | 10/1947 | New Orleans & Lower Coast (Missouri Pacific) #9014 | 1962 | Retired on 7/29/1983. Operated for a time on the New York Cross Harbor Railroad #23. Scrapped in 2006. |

| 24 | S1 | Alco | 75527 | 10/1947 | New Orleans & Lower Coast (Missouri Pacific) #9015 | 1962 | Out of service in May, 1978. Retired on 8/17/1983. Acquired by the New York Cross Harbor Railroad for parts. Scrapped in 1986. |

| 25 | S1 | Alco | 74962 | 10/1946 | Erie Railroad #307 | 1968 | Retired on 8/17/1983. Acquired by the New York Cross Harbor Railroad as #25. Permanently retired in 2000. Currently on display in Riverside Park as New York Central #8625. |

| 26 | S1 | Alco | 75354 | 10/1947 | Erie Railroad #313 | 1973 | Acquired by the New York Cross Harbor Railroad for parts. Scrapped in 1986. |

Official Guide Listing (1952)

Conclusion

The history of the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal is a compelling chapter in New York City's industrial saga. Emerging in response to the burgeoning industrial demands of the late 19th century, the BEDT played an indispensable role in the movement of goods, facilitating the growth and prosperity of Brooklyn's industrial sectors.

Its operations, marked by innovative adaptations and peak wartime efficiency, reflect the broader evolution of transportation and logistics technologies.

The eventual decline of the BEDT underscores the dynamic and often challenging nature of industrial and economic shifts.

The rise of alternative transportation modes, coupled with changing industrial landscapes, prompted the terminal's dissolution. Yet, its legacy remains etched in the physical and historical fabric of Brooklyn.

Today, the adaptive reuse of the BEDT's infrastructure and the concerted efforts to document and preserve its history ensure that the terminal's contributions are recognized and celebrated. The revitalized waterfront areas and repurposed industrial structures stand as testaments to Brooklyn's capacity for reinvention and resilience.

The Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal's story is a microcosm of larger themes in urban and industrial history. It highlights the interplay between technological advancement, economic forces, and urban development.

As such, it offers valuable insights and lessons for understanding the complex and ever-evolving nature of cities and their industrial pasts.

Recent Articles

-

Wisconsin Christmas Train Rides In Trego!

Dec 16, 25 07:22 PM

Among the Wisconsin Great Northern's most popular excursions are its Christmas season offerings: the family-friendly Santa Pizza Train and the adults-only Holiday Wine Train. -

Vermont's 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides

Dec 16, 25 07:16 PM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Rhode Island's 'Wine Tasting' Train Rides

Dec 16, 25 06:50 PM

It may the smallest state but Rhode Island is home to a unique and upscale train excursion offering wide aboard their trips, the Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad.

Contents

World War II and Peak Operations

Post-War Challenges and Decline

Revitalization and Adaptive Reuse