Buffalo Central Terminal, An Historic Station Saved From Demolition

Last revised: September 9, 2024

By: Adam Burns

Buffalo Central Terminal (BCT) is a facility that should have never been built. The mighty New York Central funded the construction of this magnificent structure during the end of the “Golden Age” of rail travel.

The railroad hoped Buffalo would continue to blossom into a great metropolis during the industrial age, rivaling the likes of Philadelphia, New York, or even Pittsburgh.

History

Alas, this never happened and BCT never reached the capacity for which it was intended. Today, the station still stands as a mere shadow of its former self having been neglected for decades.

During 1997 the Central Terminal Restoration Corporation acquired the property with hopes of seeing it restored to its former glory, perhaps even seeing rail service return.

A more pressing need, of course, is having the facility fully restored and returned to use in some capacity.

Pictures

For the last several decades the terminal has looked like this, decaying and in disrepair. This photo and the one below was captured on June 2, 2007.

For the last several decades the terminal has looked like this, decaying and in disrepair. This photo and the one below was captured on June 2, 2007.Buffalo has long been a prominent commercial hub in New York, situated at the eastern tip of Lake Erie and confluence of the Niagara River.

As Brian Solomon notes in his book, "Railway Depots, Stations & Terminals," the city historically was the state's second-most important metropolitan region. For these two reasons it became a principal meeting point for several railroads.

During the city's peak years of economic prosperity these included:

- New York Central

- Pennsylvania

- Lehigh Valley

- Erie

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western

- Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh (later Baltimore & Ohio)

- Nickel Plate Road (New York, Chicago & St. Louis)

- Michigan Central (NYC)

- Wabash.

However, only the NYC provided through service to western points such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago.

In additional, Central was the only system to offer two main lines west of the city; its main line in the States ran the southern shore of Lake Erie while its ownership of the Michigan Central provided another route through southern Ontario via the Canada Southern Railway.

Buffalo can trace its railroad heritage back to 1831 when the first promoters attempted to construct a line from the city to Hudson River.

Unfortunately, lack of funding curbed these initial efforts. The first actually put into service using steam locomotives was the Buffalo & Niagara Falls Railroad chartered in 1834.

According to "The Buffalonian" service was launched between Black Rock and Tonawanda on August 26, 1836.

The B&NF later became part of the New York Central. In the following years the railroads mentioned above, and other smaller short lines, reached Buffalo.

The NYC's first passenger depot in the city was constructed by subsidiary Attica & Buffalo (a small line chartered in 1836 and opened from Buffalo to Attica on November 24, 1842). It was a small brick building located along Exchange Street and opened during 1848.

After this structure burned a few years later it was replaced by another, which opened in 1855. There were several improvements carried out on this building during the late 19th century including the addition of a 120 foot-wide train shed.

Unfortunately, the Exchange Street Station always suffered from an operational bottleneck given its stub-end design and by the 20th century was also having capacity issues due to its increasing passenger traffic.

Even after NYC opened Central Terminal the railroad maintained a presence at Exchange Street, largely due to the former's poor location so far from the downtown area.

On November 13, 1935 it shuttered this downtown depot but made plans in conjunction with the city to build a new, but smaller, facility at the same site. This final station was opened on August 2, 1952, planned in conjunction with the Skyway construction project.

Today, the little one-story brick building still serves Amtrak and is the carrier's primary stop in the downtown Buffalo area hosting the Maple Leaf (New York – Toronto) and Empire Service (New York – Niagara Falls):

Other Buffalo Stations

While the New York Central is credited with operating the most opulent passenger station in Buffalo the city fielded a handful of other facilities maintained by the different railroads reaching there.

As early as 1899 efforts were put into motion for a union station served by every system. However, while some companies shared facilities with others no agreement could be reached.

As a result, Buffalo boasted four prominent stations. Perhaps most notable, aside from the Central Terminal, was the Lackawanna's located along the Buffalo River waterfront on Main Street at what is today South Park Avenue and Illinois Street.

The DL&W's first depot was a small wooden structure opened in 1882. Largely a temporary facility the building was replaced with a more permanent station in 1885.

Around World War I the railroad made plans to construct a beautiful terminal designed by architect Kenneth M. Murchison. It opened in 1917 and served the railroad into the early Erie Lackawanna era.

The Erie Railroad, the other major trunk line to connect New York City with Chicago, opened a modest brick facility near NYC's downtown depot at the corner of Exchange and Michigan Streets.

Finally, the Lehigh Valley constructed a small but ornate four-story depot at 125 Main Street.

It was also the work of Kenneth Murchison and featured eight grand Corinthian columns of white marble on the main façade.

The rest of the building was constructed of Indiana limestone. Its main features included a ticket office, barber shop, smoking room, restaurant, air-washing plant, pneumatic tube baggage checks, and tunnel connecting the terminal to the headhouse below Washington Street.

It remained in service until 1952 (it was later demolished in 1960 during construction of I-190) when the LV opened a far less attractive depot at South Ogden and Dingens Streets.

Construction

Buffalo Central Terminal was built and paid for entirely by the New York Central. The NYC's decision to build this new facility was two-fold:

- It would shutter two aging and cramped structures located in the downtown area of Buffalo (Exchange Street and Terrace Station, the latter of which had opened in the early 1880s to serve Niagara Falls bound traffic using the new "Belt Line").

- Make operations more efficient with a "through" structure located along the New York-Chicago main line.

By doing so trains would no longer have to deal with the cumbersome issue of backing into and out of the terminal.

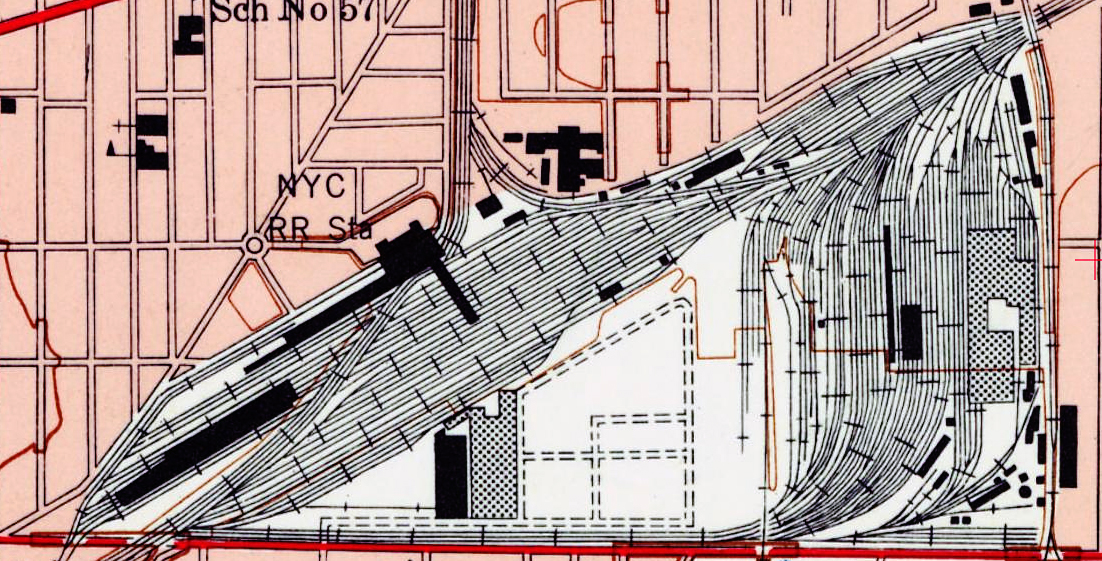

This idea did have a considerable drawback, the station would be located 2.5 miles from the downtown area although the railroad hoped the growing city would eventually encompass the east-side area.

The NYC had also envisioned other railroads joining it but, alas, the location pushed other tenants away and ultimately only the small Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo used the terminal.

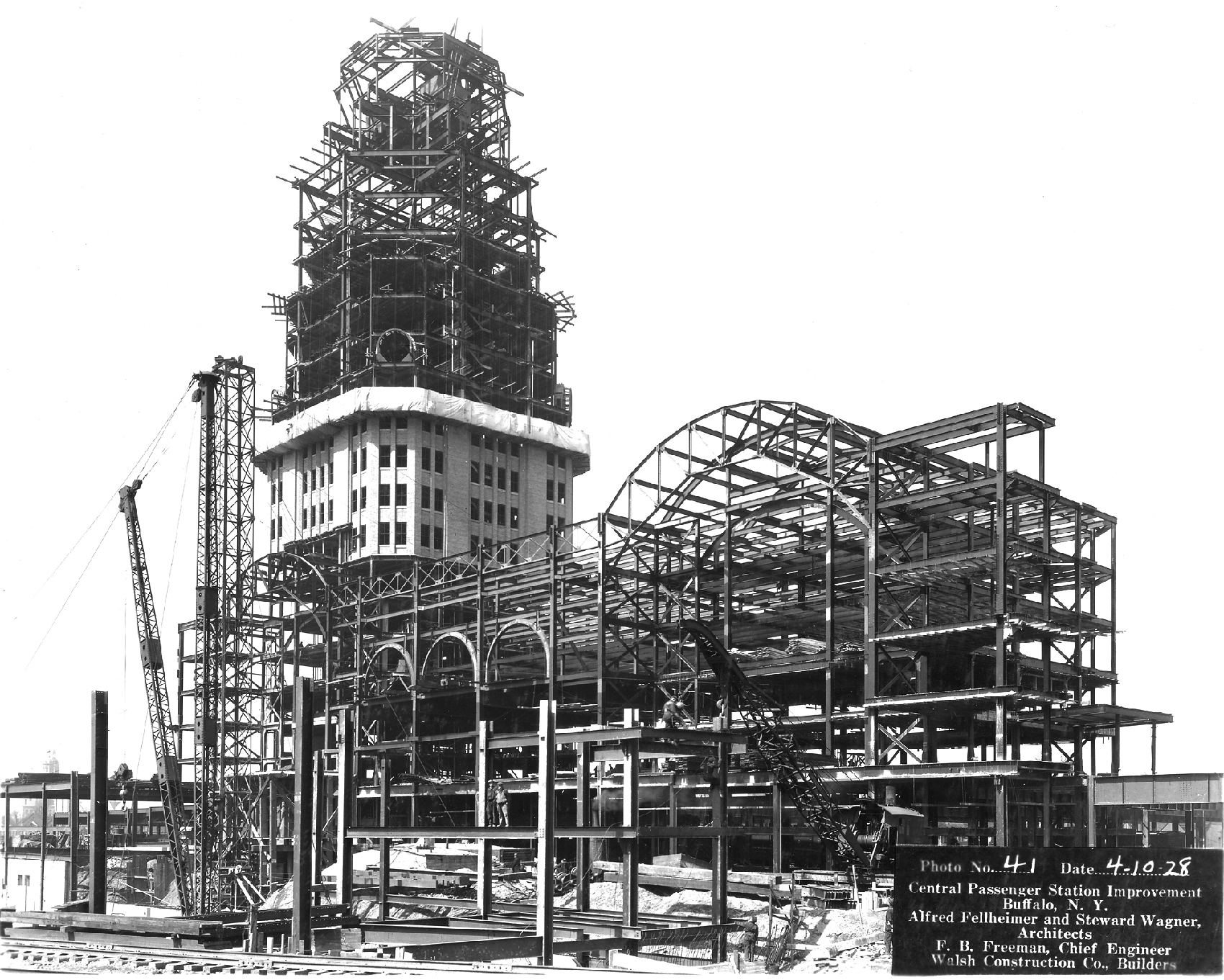

The architect chosen was Fellheimer & Wagner of New York City, which among their other accomplishments included the Cincinnati Union Terminal opened around the same time.

As Solomon notes the firm drew its inspiration from Helsinki Station, conceived by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, the primary terminal for his home country's capital. It had opened during 1914 and was designed in the Art Nouveau style featuring Finnish themes and liberal use of reinforced concrete.

In addition to Saarinen's work, Central Terminal featured Art Deco touches the dominating theme of the 1920s and '30s. Planning for the structure began in 1926 with actual construction commencing a year later.

Its dominating feature was a magnificent 16-story office tower rising 271 feet over the surrounding landscape, along with a five-story main concourse area. The concourse was nearly 60 feet tall and measured some 225 feet long by 66 feet wide.

Other features included restaurants, a Pullman Company maintenance facility, ice house, Railway Express Agency building, and even its own power plant! It opened to the public on June 23, 1929 and was immediately hailed as a Buffalo landmark.

Track Layout

Unfortunately, it seems fate befell the Central more than other roads. When it attempted to rechristen its Empire State Express as a streamliner in 1941 it chose the date of December 7th.

In this case, Buffalo Central Terminal opened just months before the stock market crash and while built to handle 10,000 daily passengers never approached this level of business, even during the bustle of World War II.

During its heyday it played host to Central’s most famous passenger train, the 20th Century Limited, along with other notable services such as the Chicagoan, Commodore Vanderbilt, Lake Shore Limited, Empire State Express, New England States, Pacemaker, and others.

When one looks at the station today it is hard to imagine the beautiful architecture and ornate decoration it once boasted. Over the years vandals have stripped it of nearly everything of value.

Decline

As early as the 1950s unfolded it was clear the passenger train was in serious decline, Americans loved their cars and airliners were a faster mode of travel.

At this time the NYC, facing increasing financial problems, attempted to rid itself of the terminal putting it up for sale in 1956 (along with more than 400 other stations). Alas, only 50 were sold an no buyers were found for the Buffalo facility.

In 1966 the railroad demolished the Pullman building, coach shop, ice house, and power house to reduce its property tax burden. As the crisis worsened the terminal continued on under NYC and then Penn Central following the 1968 merger with PRR.

In 1971 Amtrak took over operations and Conrail acquired the building in its 1976 startup. Amtrak did not have the capital to overhaul the building and discontinued service in 1979.

It moved its only through train, the Lake Shore Limited, to nearby Depew, New York and dispatched regional Empire Service trains from downtown Exchange Street (a setup that continues to this day).

In 1984 the terminal was placed on the National Register of Historic Places although this did not guarantee the building’s future. Left vacant and abandoned it was severely looted during the next two decades.

In addition, various owners used it for storage and stripped most of its interior valuables. By the 1990s the station was nothing more than an eyesore and in real danger of being demolished. It likely would have been razed if not for the millions required to do so.

Then, a group of Buffalo preservationists stepped in and purchased the building for a mere $1 in 1997 and later formed the Central Terminal Restoration Corporation.

During the last several years they have been successful in shoring up the building and stabilizing the structure to allow for further restoration efforts (in that time they have been able to secure $1 million in state grant money as well as thousands in donations).

For more information regarding the ongoing restoration efforts with the terminal please visit the group’s website by clicking here.

The long-term of goal of the terminal is to see it fully restored and, hopefully, used in some type of rail capacity once more. However, attempts at finding tenants or a real estate developer have unsuccessful to date.

Additionally, the use of the building to serve trains has also come into question given the poor neighborhood in which it is now located along with the fact that Amtrak has stated it does not really serve the carrier's needs because it is situated so far from the downtown area.

In recent years the terminal, among all things, has become best known by the public for its appearances on reality ghost hunter television shows.

Master Plan (2021)

The building's Master Plan, outlined here by the Central Terminal Restoration Corporation in August 2021, looks to see the building and grounds converted into a multipurpose center tailored towards a wide range of areas.

The plan essentially looks to see the terminal become a community oriented center aimed at revitalizing the local region. If full funding is achieved, with a total price tag believed to be between $276.5 and $296.5 million, the 523,000 square foot property will include offices and housing indoors and open spaces outdoors.

Officially, the Master Plan states the building will look "...to create a mix of creative, entrepreneurial and civic enterprises such as: Innovation Hub; Film Industry; Cultural Center; Community and Non Profit Anchor; and Housing."

$61 Million Boost

The hope to see the Master Plan realized received a major boost when Governor Kathy Hochul announced Buffalo Central Terminal would receive $61 million in state funding.

This is by far the greatest amount of money put into the structure since the New York Central opened the facility in 1929. According to the governor:

"The Central Terminal is a key anchor of the holistic economic development strategy for Buffalo’s East Side, which focuses on community wealth building. People are passionate about the iconic structure and have wanted to see it revitalized for decades, and it is just one part of a plan that is designed to make big investments to generate transformational improvements for the community.”

The money will be used to carry out emergency repairs and stabilization including:

- Repairing falling masonry on the terminal and tower buildings.

- Installation of a fire detection system.

- Asbestos remediation.

- Window replacement.

- New plumbing and electrical.

- Installation of heat and cooling systems.

- New bathrooms.

- Flat roof repairs.

- Gaustavino tile stabilization and repair (concourse).

- Catering kitchen addition.

- Sidewalk improvements.

- Landscape enhancements.

- "Civic Commons" addition to the outside grounds.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Maine Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 21, 25 12:58 PM

Maine's railroads have long been associated with logging and agriculture. Today, a number of museums honoring this heritage can be found throughout the state. -

Kentucky Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 20, 25 03:17 PM

Kentucky has long contained a mix of important through main lines and rich bituminous coal seams for the railroad industry. Today, a handful of museums can be found across the state. -

Kansas Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 20, 25 02:58 PM

Located within the Heartland, Kansas has always been an important agricultural state for railroads. A number of museums can be found throughout the state.