Atlantic Coast Line Railroad: "Standard Railroad of the South"

Last revised: October 14, 2024

By: Adam Burns

The Atlantic Coast Line, also known as the ACL or Coast

Line, was synonymous with the South and served points north to Richmond,

Virginia; south to Florida; west to Birmingham; and finally the important ports of Norfolk, Wilmington, and Charleston.

The railroad spent most of its corporate existence as a very profitable, well-managed operation despite strong competition from the nearby Seaboard Air Line and Southern Railway. Visually, ACL held one of the most unique paint schemes ever-adopted by a Class I railroad.

Thanks to the legendary styling department at General Motors its first-generation diesels wore a beautiful purple and silver livery with yellow trim. The scheme was ultimately retired in the 1950s and never applied to second-generation locomotives.

Remembered in the likes of the Southern for its sound business practices, Coast Line was a highly respected railroad which never faced a serious financial crisis.

As the merger movement picked up it found a partner in one-time rival Seaboard. The union proved much more successful than the later Penn Central and the Seaboard Coast Line later went on to form part of today's CSX Transportation.

Photos

An Electro-Motive company photo featuring a gorgeous A-B set of new Atlantic Coast Line F7's circa 1951. Alas, the harsh Southern sun made it difficult to maintain the purple's brilliance and it was simplified in the 1950's.

An Electro-Motive company photo featuring a gorgeous A-B set of new Atlantic Coast Line F7's circa 1951. Alas, the harsh Southern sun made it difficult to maintain the purple's brilliance and it was simplified in the 1950's.History

The Atlantic Coast Line began life like many classic railroads, put together through a series of mergers with smaller systems. There were five primary components of the original ACL. Its earliest predecessor was the Petersburg Railroad, chartered in 1830.

It opened for service a few years later between its home city and Garysburg, North Carolina, just across the Roanoke River from Weldon.

At Petersburg, a connection was opened with the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad, chartered in 1836. It was completed between its namesake cities in 1838 and, together, the two roads provided a direct route from Richmond to the Tarheel State.

As the 1840s dawned more connections from the south extended through service into South Carolina and beyond. The Wilmington & Raleigh Railroad, chartered in 1834, opened between Wilmington and Weldon in 1840 (Wilmington became the ACL's headquarters until its move to Jacksonville in 1960).

It was unsuccessful in ever reaching the state capital and a result renamed as the Wilmington & Weldon in 1855. The next ancestor was the Wilmington & Manchester Rail Road, chartered in 1846 and completed in 1853 from Wilmington to Manchester, South Carolina.

Formation

Finally, the North Eastern Railroad, chartered in 1853, opened from the port of Charleston, South Carolina to a connection with the W&M at what later became Florence in 1857. All five carriers operated independently until, and after, the Civil War.

According to Larry Goolsby's book, "Atlantic Coast Line Passenger Service: The Postwar Years," the first use of the name Atlantic Coast Line occurred in 1871 when the consortium came under the control of William T. Walters, a Baltimore investor. After that time they worked together under the banner, "Atlantic Coast Line Fast Mail Passenger Route."

An American Locomotive photo featuring new Atlantic Coast Line C630 #2011 (one of three Coast Line purchased) at the company's plant in Schenectady, New York circa 1965. Warren Calloway collection.

An American Locomotive photo featuring new Atlantic Coast Line C630 #2011 (one of three Coast Line purchased) at the company's plant in Schenectady, New York circa 1965. Warren Calloway collection.Expansion

The name was first, officially used in 1893 when all five were placed under the new holding company, Atlantic Coast Line Company. In 1900, the group was formally merged into the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad.

Within just a few years the new ACL was again expanding and acquired its largest single interest in 1902 reaching an agreement that year with Henry B. Plant to purchase his Plant System.

This collection of railroads connected with the ACL at Charleston and reached Savannah, Montgomery, Albany, Jacksonville, and other points throughout Florida. They constituted the bulk of ACL's network south of Charleston.

At A Glance

Wilmington, North Carolina (1900-1960) Jacksonville, Florida (1960-1967) | |||||||||

Richmond, Virginia - Charleston, South Carolina - Savannah, Georgia - Jacksonville - Orlando - Tampa, Florida Wilson - Wilmington, North Carolina Wilmington - Pee Dee, South Carolina Winston-Salem - Florence, South Carolina Florence - Atlanta Brunswick, Georgia - Montgomery - Alabama Birmingham, Alabama - Waycross, Georgia Waycross - Albany, Georgia Albany - Dunnellon, Florida Jacksonville - St. Petersburg, Florida Dupont, Georgia - Naples, Florida | |||||||||

Freight: 170 Passenger: 62 Freight & Passenger (Dual Mode): 234 Switchers: 119 Freight Cars: 28,847 Passenger Cars: 405 |

Plant's earliest component was the Atlantic & Gulf, acquired in November of 1879 when the road went bankrupt and reorganized as the Savannah, Florida & Western. It connected Savannah with Bainbridge, Georgia but was soon expanded to Jacksonville, Live Oak, Gainesville, and Chattahoochee in Florida as well as Waycross (Georgia).

In 1882 he formed the Plant Investment Company as a holding company for his railroad portfolio. In 1893 he added the South Florida Railroad, a one-time narrow-gauge (3-foot) property (standard-gauged in 1886) which had opened a route between Sanford and Tampa by early 1884.

Atlantic Coast Line F3A #343, sporting F7 grills, lays over in Rocky Mount, North Carolina on November 27, 1965. American-Rails.com collection.

Atlantic Coast Line F3A #343, sporting F7 grills, lays over in Rocky Mount, North Carolina on November 27, 1965. American-Rails.com collection.At Tampa, Plant constructed a deep water port and the city grew into an important commercial center along Florida's Gulf Coast. His final major acquisition was the 1899 takeover of the Jacksonville, Tampa & Key West Railway.

This road linked Jacksonville with Sanford, completed in 1886. After Plant gained controlled he renamed it as the Jacksonville & St. Johns River Railway.

Several smaller roads added to the Plant System, which were merged into the SF&W included the following: the Green Pond, Walterboro & Branchville; Ashley River Railroad; Abbeville Southern Railway; Southern Alabama Railroad; Alabama Midland Railway; Brunswick & Western; and Charleston & Savannah.

Logos

One of the Plant System's final endeavors before ACL ownership was completing the Folkston Cutoff in 1901 as a shortcut between Folkston and Jesup, Georgia to bypass Waycross.

Other important towns served by the Plant System included Punta Gorda, St. Petersburg, and Palatka, Florida as well as Albany and Thomasville, Georgia. In 1897, the ACL again expanded its portfolio, acquiring the Charleston & Western Carolina Railway.

The addition of this property began a series of transactions in which the company gained a controlling interest in surrounding roads with which it interchanged. The C&WC connected with the "West Point Route" at Augusta; to the south, reaching Port Royal, South Carolina while to the north it linked Anderson, Greenville, and Spartanburg.

Its lines totaled 340 miles. In 1899, the Coast Line took part in a business deal with the L&N giving it joint ownership of the previously-mentioned, "West Point Route."

This small regional included the Georgia Railroad, Atlanta & West Point, and Western Railway of Alabama. The latter two roads were controlled by the former running from August to Selma via Montgomery and Atlanta. There were also branches to Macon and Athens. the West Point Route takeover

In 1902, ACL gained control of the Louisville & Nashville, a prosperous road serving most of Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, the Florida Panhandle, and New Orleans. This in turn added the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis which the L&N had long presided over.

In 1925 the L&N and ACL jointly leased the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio (the "Clinchfield"); the CC&O was a small but rich 302-mile road that transported black diamonds from Elkhorn City, Kentucky to a connection with the ACL at Spartanburg.

One last addition took place in 1927 when the Coast Line acquired the bankrupt 641-mile Atlanta, Birmingham & Atlantic, renaming it the Atlanta, Birmingham & Coast. The AB&C gave ACL access to the southeastern cities of Birmingham, Alabama and Atlanta, Georgia via Waycross.

Its final expansion of any kind occurred a year later in 1928 when opening the Perry Cutoff between Thomasville and Dunnellon, Florida which offered a quick shortcut to the Midwest via Montgomery and New Orleans.

In all, the ACL's own lines comprised about 5,575 miles. However, including subsidiaries it boasted a gigantic system of nearly 12,000 miles serving nearly every major southeastern market from Kentucky and Virginia to Alabama and Florida.

20th Century

It seems that nearly all of the South's major Class I carriers were well-managed, efficient operations; the Southern, L&N, Seaboard Air Line, Florida East Coast, Norfolk & Western, and Atlantic Coast Line were all profitable companies.

The ACL never flirted with a serious financial disaster. Even when the Great Depression the ACL weathered the immediate storm and succeeding lean years of the 1930s by carrying out sound business practices, watching its pennies, and maintaining a diversified portfolio in roads like the L&N.

The company was so confident from an early era it used the slogan, "Standard Railroad of the South," a nod to the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad.

After the depression, ACL spent considerable resources upgrading its infrastructure for improved freight and passenger service by increasing train speeds and overhauling its classification yards.

According to Mike Schafer's book, "Classic American Railroads: Volume III," between 1939 and 1951 it had invested some $268 million into its property making it a first-class operation.

It continued to spend on such investments into the 1950s with a particular eye on freight operations by double-tracking its main spine from Virginia to Florida.

However, the company also placed an importance on passenger trains. For instance, as Mr. Goolsby notes, ACL increased passenger train speeds to 90 mph by the 1950s and even briefly flirted with 100 mph operations.

System Map (1940)

The ACL and Seaboard were the only two carriers providing direct service from the Northeast to Florida. As a result, its trains remained profitable through the 1960s, forcing it to continue building new stations until that time!

A rarity in that era, the strong patronage was thanks to vacationers flocking to the Sunshine State's beaches and tropical climates.

The ACL was quick to adopt the diesel locomotive, acquiring its first two examples, E3A's #500 and #501, in November of 1939.

These streamlined locomotives were power for the all new Champion launched a month later between New York/Boston and Miami in direct competition against Seaboard's Silver Meteor which hit the rails on February 2nd that year.

As the diesel quickly proved its worth Coast Line hastened the transition after World War II. Mr. Schafer notes that immediately after the war it rostered just over 100 such units. However, by 1952 that figure had ballooned to 564. Only a few years later, Coast Line completed the transition in 1955.

The road was always a big proponent of Electro-Motive's products owning everything from first-generation F7's to second-generation SD45's. However, it dabbled with products from Baldwin (Vo-1000) and Alco.

Passenger Trains

It should be noted that the ACL reached New York via the Pennsylvania Railroad and eastern Florida via the Florida East Coast Railway. The railroad likewise ferried other railroads most prestigious trains to and from Florida.

Champion: (New York/Boston - Miami)

Everglades: (New York - Jacksonville)

Florida Special: (New York - Miami/St. Petersburg)

Gulf Coast Special: (New York - Tampa/Ft. Myers/St. Petersburg)

Havana Special: Connected New York with Key West until the devastating 1935 Hurricane which destroyed the Florida East Coast's Key West Extension.

Miamian: (Washington - Miami)

Palmetto: (New York - Savannah/Augusta/Wilmington)

Vacationer: (New York - Miami)

Interestingly, it even tried Alco's very large second-generation C628 and C630 road-switchers. Before the merger with Seaboard the company began purchasing General Electric's first cataloged models, the Universal series.

Despite Coast Line's sound management and healthy business practices it recognized the industry was entering an uncertain era after World War II.

The highway was pulling away increasing freight and passenger business while airlines were doing the same. Mergers, if planned and implemented correctly can save a railroad millions and was the very reason ACL entered such discussions with long rival Seaboard Air Line in 1958.

The two offered a great deal of savings through redundancy and elimination of duplicate trackage/facilities. In addition, unlike the later Penn Central disaster both were profitable, healthy companies in spite of their rivalries.

A consulting firm stated the merger could generate a net savings of $24.2 million annually. Typical of the Interstate Commerce Commission during that era, however, it was not approved until 1963 and not made official until July 1, 1967, creating the new Seaboard Coast Line.

Seaboard Coast Line Merger

The Atlantic Coast Line's original paint scheme in the diesel era featured an exotic livery of Royal Purple trimmed with aluminum/silver and yellow touches.

It was a stunning design credited to General Motors' legendary styling department which conceived many now-classic railroad liveries.

Unfortunately for the ACL, which dealt with the Southeast's brutal sun the purple hue faded quickly. As Mr. Goolsby points out, repaints were needed every two years just to keep the colors brilliant.

In what came down to simple economics, in 1957 under new president W. Thomas Rice the railroad changed to a simplified black design with accents of yellow and silver. It certainly was not as attractive but the company saved $100,000 annually by doing so.

Diesel Roster

American Locomotive Company

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HH-1000 | 25 | 1940 | 1 |

| S2 | 26-46 | 1942-1944 | 21 |

| HH-660 | 1900 | 1939 | 1 |

| C628 | 2000-2010 | 1963-1964 | 11 |

| C630 | 2011-2013 | 1965 | 3 |

Baldwin Locomotive Works

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO-1000 | 10-18 | 1942-1944 | 9 |

Electro-Motive Division

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW8 | 50-59 | 1952 | 10 |

| GP7 | 100-279, 1100-1104 | 1950-1951 | 185 |

| FTA | 300-323 | 1943-1944 | 24 |

| FTB | 300B-323B | 1943-1944 | 24 |

| F2A | 324-335 | 1946 | 12 |

| F2B | 324B-335B | 1946 | 12 |

| F3A | 336-347 | 1948 | 12 |

| F3B | 336B-347B | 1948 | 12 |

| F7A | 348-429 | 1950-1951 | 82 |

| F7B | 392B-403B | 1951 | 12 |

| FP7 | 430-473 | 1951-1952 | 44 |

| E3A | 500-501 | 1939 | 2 |

| E6A | 502-523 | 1940-1942 | 22 |

| E7A | 529-543 | 1945-1948 | 15 |

| E8A | 544-556 | 1950 | 13 |

| NW2 | 600-605 | 1940-1942 | 6 |

| SW7 | 643-651, 717-718 | 1950 | 11 |

| SW9 | 652-661, 719-720 | 1951-1952 | 12 |

| E6B | 750-754 | 1940-1942 | 5 |

| E7B | 755-764 | 1945 | 10 |

| E8B | 765-766 | 1949 | 2 |

| GP30 | 900-908 | 1963 | 9 |

| GP35 | 909-914 | 1963 | 6 |

| GP40 | 915-928 | 1966 | 14 |

| SD35 | 1000-1023 | 1964-1965 | 24 |

| SD45 | 1024-1033 | 1966 | 10 |

| SDP35 | 1035 | 1965 | 1 |

| SW1 | 1901 | 1939 | 1 |

General Electric

| Model Type | Road Number | Date Built | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| U30B | 975-978 | 1967 | 4 |

| U25C | 3000-3020 | 1963-1965 | 21 |

| U30C | 3021-3024 | 1966 | 4 |

Steam Roster

During the steam era the railroad had not needed big power thanks to its relatively easy grades. As a result it did not even own any articulated or Mallet designs.

Its biggest included a batch of 2-10-0's built during the World War I era and originally intended for the Russian government, twenty 2-10-2's constructed by Baldwin in 1925 (it also acquired three through the AB&C takeover), and finally a dozen 4-8-4's (known as 1800's by the railroad) acquired by Baldwin in 1938 for passenger service.

In standard operation the company largely relied on 2-8-2's in freight service and 4-6-2's handled passenger assignments while arrangements like the 4-6-0 and 2-8-0 were dual-service locomotives.

| Class | Type | Wheel Arrangement |

|---|---|---|

| A-3 | Switcher | 0-4-0 |

| C Through C-8 | American | 4-4-0 |

| D, D-2 Through D-7 | American | 4-4-0 |

| D-1 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| E Through E-13 | Switcher | 0-6-0 |

| E-14 | Switcher | 0-8-0 |

| F Through F-5 | American | 4-4-0 |

| G Through G-5 | Mogul | 2-6-0 |

| H | American | 4-4-0 |

| I, I-1, I-3 | Atlantic | 4-4-2 |

| I-2 | Columbian | 2-4-2 |

| J | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| J-1 | Mountain | 4-8-2 |

| K Through K-16 | Ten-Wheeler | 4-6-0 |

| L-1 Through L-4 | Consolidation | 2-8-0 |

| M, M-2 | Mikado | 2-8-2 |

| O | Decapod | 2-10-0 |

| P Through P-5 | Pacific | 4-6-2 |

| Q-1 | Santa Fe | 2-10-2 |

| R-1 | 1800 | 4-8-4 |

An A-A-B-A set of Atlantic Coast Line F7's hustle priority freight #175 through Dunn, North Carolina on June 20, 1965. Warren Calloway photo.

An A-A-B-A set of Atlantic Coast Line F7's hustle priority freight #175 through Dunn, North Carolina on June 20, 1965. Warren Calloway photo.CSX Transportation

As predicted, the SCL became a very profitable venture for 13 years before merger mania again struck during the 1980s. By that time it had slowly integrated its other properties, including the West Point Route, L&N, and Clinchfield, into the new marketing name known as "The Family Lines."

The moniker held no corporate power until December 29, 1982 when the group was formally merged into Seaboard System.

The holding company, CSX Corporation, had been created on November 1, 1980 to eventually merge the Seaboard roads and Chessie System lines into a new company. That railroad was formed on July 1, 1986 when CSX Transportation (CSXT) was born.

It immediately absorbed the Seaboard System roads while the Chessie's subsidiaries, B&O and Chesapeake & Ohio, disappeared a year later in 1987 (the Western Maryland had vanished in 1983). Today, many lines of the ACL remain in use by the Class I while others have been shed to short lines or abandoned.

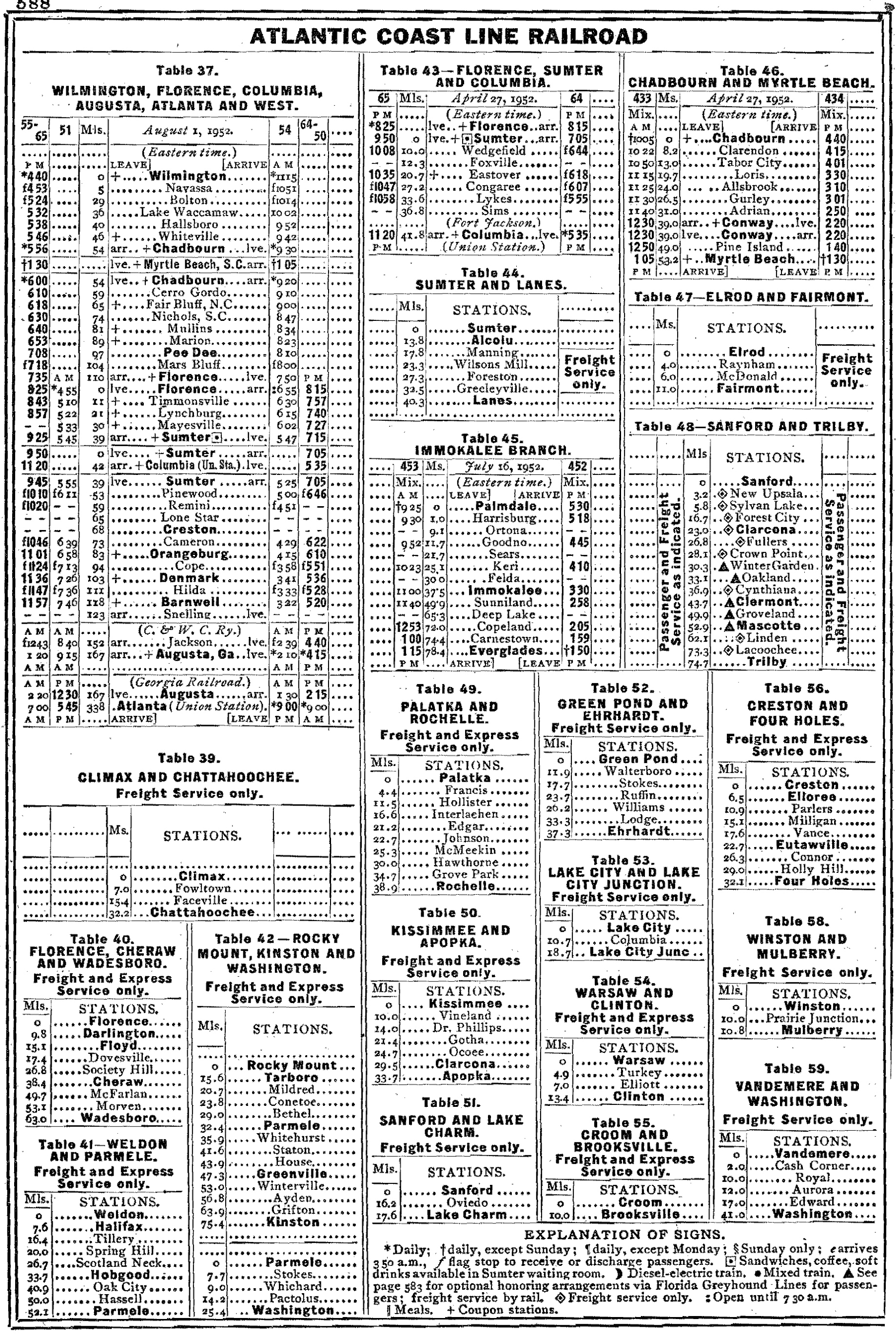

Timetables (August, 1952)

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works

Feb 21, 25 12:30 AM

The Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works was a major U.S. manufacturer throughout the 19th century, specializing in locomotives and heavy machinery. It merged with Alco in 1905. -

Norris Locomotive Works: Major 19th Century Builder

Feb 21, 25 12:24 AM

The Norris Locomotive Works was the preeminent locomotive builder through the mid-19th century until the family owned business voluntarily ended prodution in 1866. -

Peoria and Eastern Railway

Feb 20, 25 11:24 PM

The Peoria and Eastern Railway was a notable subsidiary of the New York Central with a heritage tracing back to the 1830s. Much of the system was abandoned in Illinois by the 1990s.