"20th Century Limited" (Train): Map, Consist, Schedule, Interior

Last revised: February 24, 2o25

By: Adam Burns

The New York to Chicago corridor was one of the most hotly contested passenger markets east of the Mississippi and New York Central’s 20th Century Limited competed with Pennsylvania Railroad's Broadway Limited for top honors, a rivalry which persisted for decades (based from historic traffic figures the Century did have a slight edge over the Broadway).

Few trains have carried the aura of Central's original streamlined version of the Limited, which featured perhaps the greatest example of shrouding ever applied to a steam locomotive.

As flag bearer of the "Great Steel Fleet" the Limited's service was second-to-none, matched only by the Broadway Limited.

Perhaps only the Santa Fe held its trains in higher regard than the New York Central. The Vanderbilt road took great pride in its fleet, particularly the Limited.

In a move that arguably spoke volumes of the impending merger, NYC officials elected to cancel the train prior to the Penn Central merger. The final westbound run left Track #34 from Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan a 6 PM on the evening of December 2nd that year.

Photos

A New York Central "Dreyfus Hudson" has train #26, the eastbound "20th Century Limited," hustling past the Studebaker plant in South Bend, Indiana, circa 1938. Patty Allison colorized photo.

A New York Central "Dreyfus Hudson" has train #26, the eastbound "20th Century Limited," hustling past the Studebaker plant in South Bend, Indiana, circa 1938. Patty Allison colorized photo.History

The 20th Century Limited traces its history back to 1902 when it was originally inaugurated that year between New York and Chicago (the Pennsy began running a similar plush train between the two cities that year as well; known as the Pennsylvania Special it was renamed the Broadway Limited in 1912).

For the first thirty years both the Limited and Broadway were quite conservative and changed little aesthetically, using standard heavyweight passenger equipment and traditional steam locomotives. However, when the streamliner craze took root in the 1930s everything changed.

The New York Central was the first of the rivals to begin dabbling in the new concept. During 1936 it rebuilt and modernized heavyweight cars (taking a cue from the B&O) for the its new Mercury, running between Detroit and Cleveland.

At A Glance

Grand Central Terminal (New York) LaSalle Street Station (Chicago) |

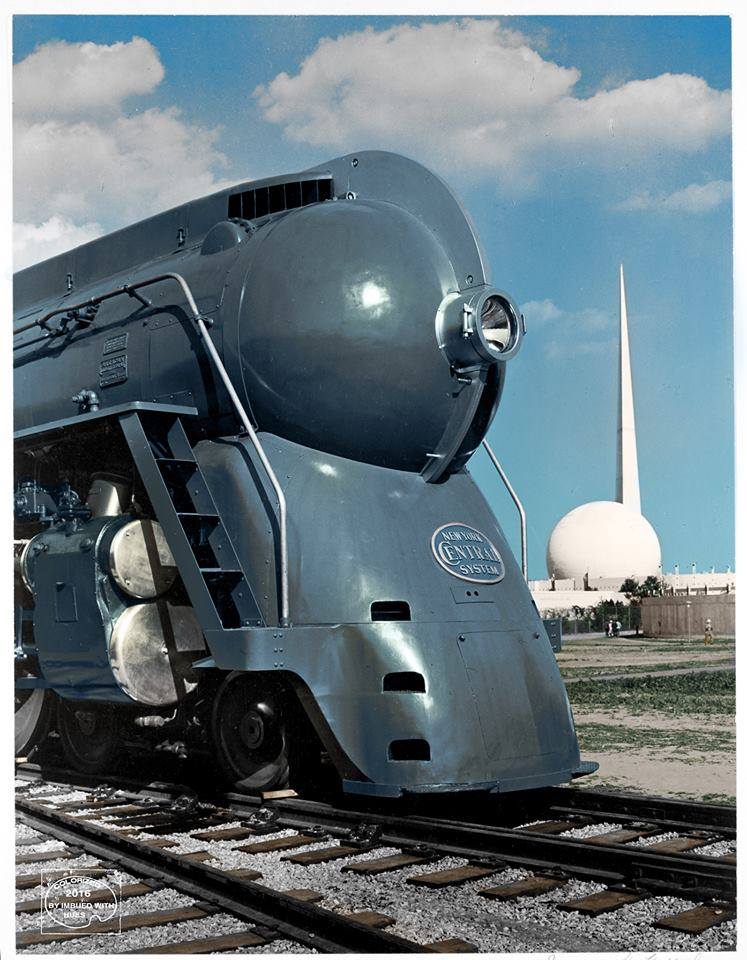

One of the legendary "Dreyfuss Hudsons" (J-3a), which powered the original version of New York Central's streamlined "20th Century Limited." The locomotive is seen here on display at the New York World's Fair in 1939. Photo colorized by Patty Allison.

One of the legendary "Dreyfuss Hudsons" (J-3a), which powered the original version of New York Central's streamlined "20th Century Limited." The locomotive is seen here on display at the New York World's Fair in 1939. Photo colorized by Patty Allison.Rather pleased with the train's ridership results the train brought Central began strongly considering upgrading its flagship.

With no streamlined train yet of it’s own the Pennsylvania approached the Central wondering if the latter would be interested in a joint effort of streamlining their flagships.

The two parties ultimately agreed to the endeavor, which was more about saving money than any kind of common partnership; by placing their order together they reaped the benefits of reduced costs. The builder of their trains was the industry standard of the day, the Pullman-Standard.

What’s interesting is that both roads' sets of cars were virtually identical from a blue-print standpoint although here, the similarities ended since each company chose different industrial designers to decorate and style their trains.

Route Map

Interior

With its order of 62 cars ready to receive their interior and exterior cosmetic touches the Central tapped distinguished industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss.

What he created has been argued as the most beautiful and endearing passenger train ever created. While that point is certainly debatable Dreyfuss undoubtedly brought to life a stunning train.

To create Central’s flagship Dreyfuss used a process of keeping elements in their basic form when laying out different aspects of the train (a concept known as “cleanlining”).

Similarly Dreyfuss kept the theme of New York City and urban settings throughout the train and used tones of light and gunmetal grey for the interior and exterior (this was particularly stunning inside, matched against the urban theme).

For instance, the diners served double duty. During the day they were used in their as-intended function, providing exceptional meals that rivaled the most exquisite restaurants of the day (or today).

In this wonderful scene by staff photographer Ed Nowak, a pair of New York Central E7A's are staged with the flagship "20th Century Limited" at Garrison, New York in September of 1948. This newly-equipped, postwar version of the "Limited" featured an RPO, several Pullman sleepers in various configurations, diner, club-lounge (featuring a shower, buffet, radio-telephone, barber-valet, and secretary), and lounge-buffet-observation.

In this wonderful scene by staff photographer Ed Nowak, a pair of New York Central E7A's are staged with the flagship "20th Century Limited" at Garrison, New York in September of 1948. This newly-equipped, postwar version of the "Limited" featured an RPO, several Pullman sleepers in various configurations, diner, club-lounge (featuring a shower, buffet, radio-telephone, barber-valet, and secretary), and lounge-buffet-observation.However, after the final evening meal was served the white tablecloth linens would be replaced with rust-red linens and the car would become a nightclub known as “Café Century.”

Dreyfuss also broke up the diners to make passengers feel less like they were in railroad cars and more as if they were in an actual restaurant using glass wall partitions. Perhaps Dreyfuss’ crowning achievement with the Limited his layout of the sleeper-observation.

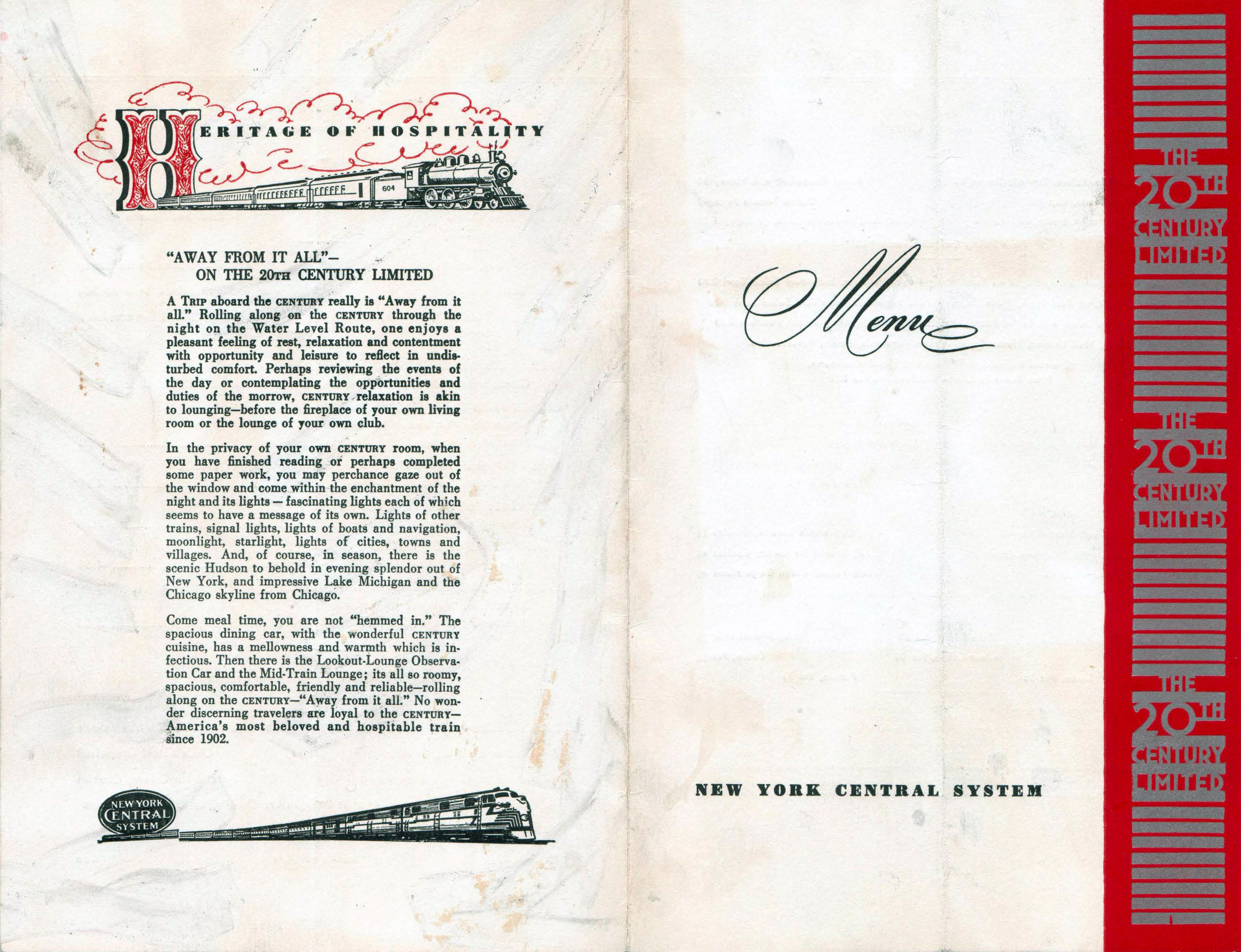

Menu

Here he used urban murals, soft lighting, the train’s ubiquitous gunmetal gray colors, and touches of partitioning to group passengers together in seating of twos or threes (which featured blue leather upholstery).

Coupled with Art Deco artistry and the car was something to behold. As Loewy had done with the Broadway, in the 20th Century Dreyfuss, near the back of the car, partitioned the observation.

Drumhead

He sectioned off the extreme end of the car (by way of a large urban mural and a rounded loveseat with table) with seats facing towards the windows so passengers could watch the landscape retreating away from them; at the time this was quite a radical change from traditional layouts.

Unlike the Pennsylvania, which interestingly never bothered to match its locomotives with the rest of train, Dreyfuss and the Central kept everything linear using tones of gray for the livery. For power the train was led by specially streamlined 4-6-4 Hudsons.

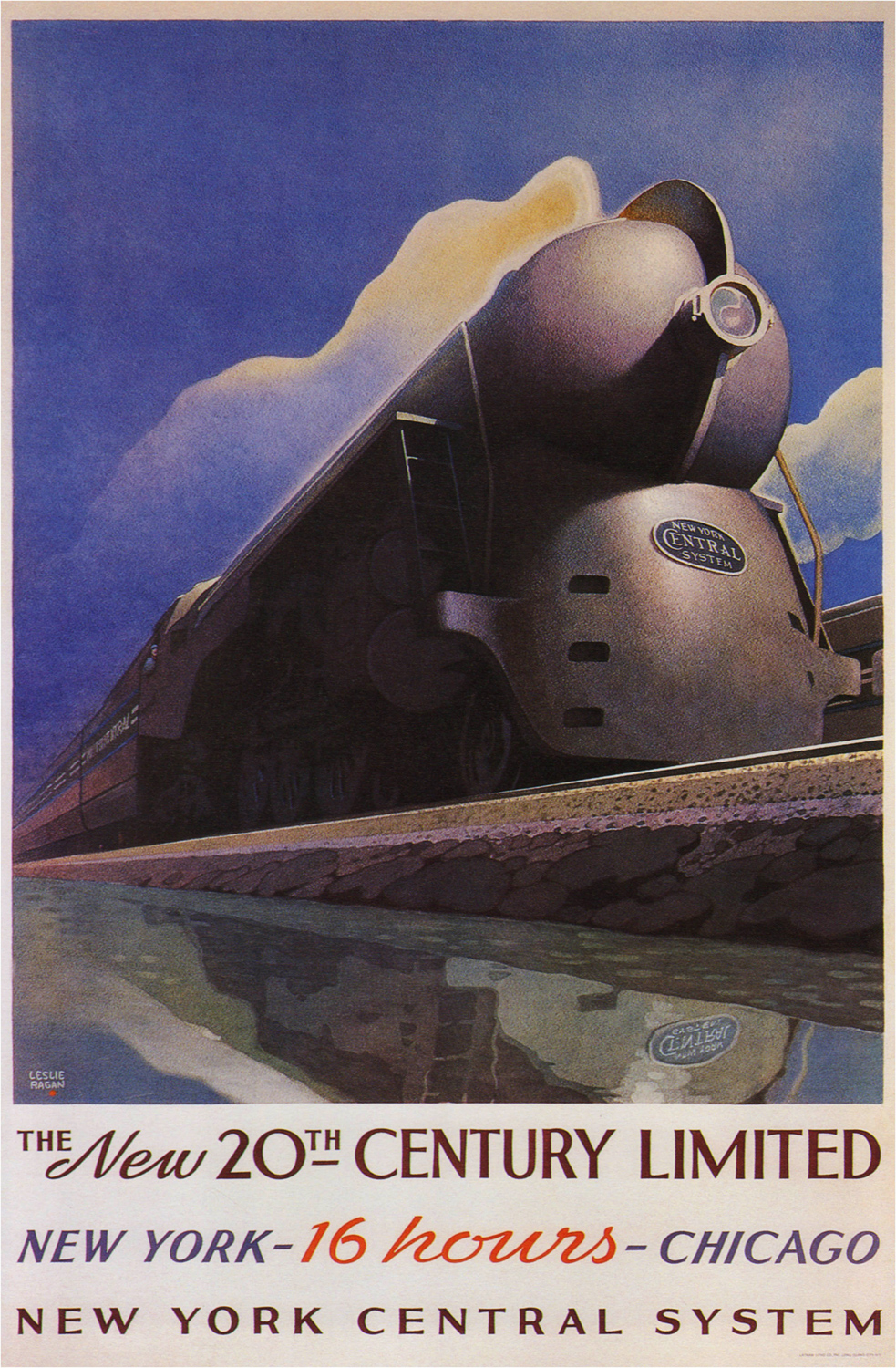

One of the famous railroad paintings of all time was Leslie Ragan's piece featuring the original "20th Century Limited."

One of the famous railroad paintings of all time was Leslie Ragan's piece featuring the original "20th Century Limited."The New York Central owned many examples of this locomotive type but only the Class J3a's received the beautiful treatment, ten in particular; #5445-5454.

The steamers were manufactured in 1938 by the American Locomotive Company (Alco) and in a rare case had their streamlining applied at the factory.

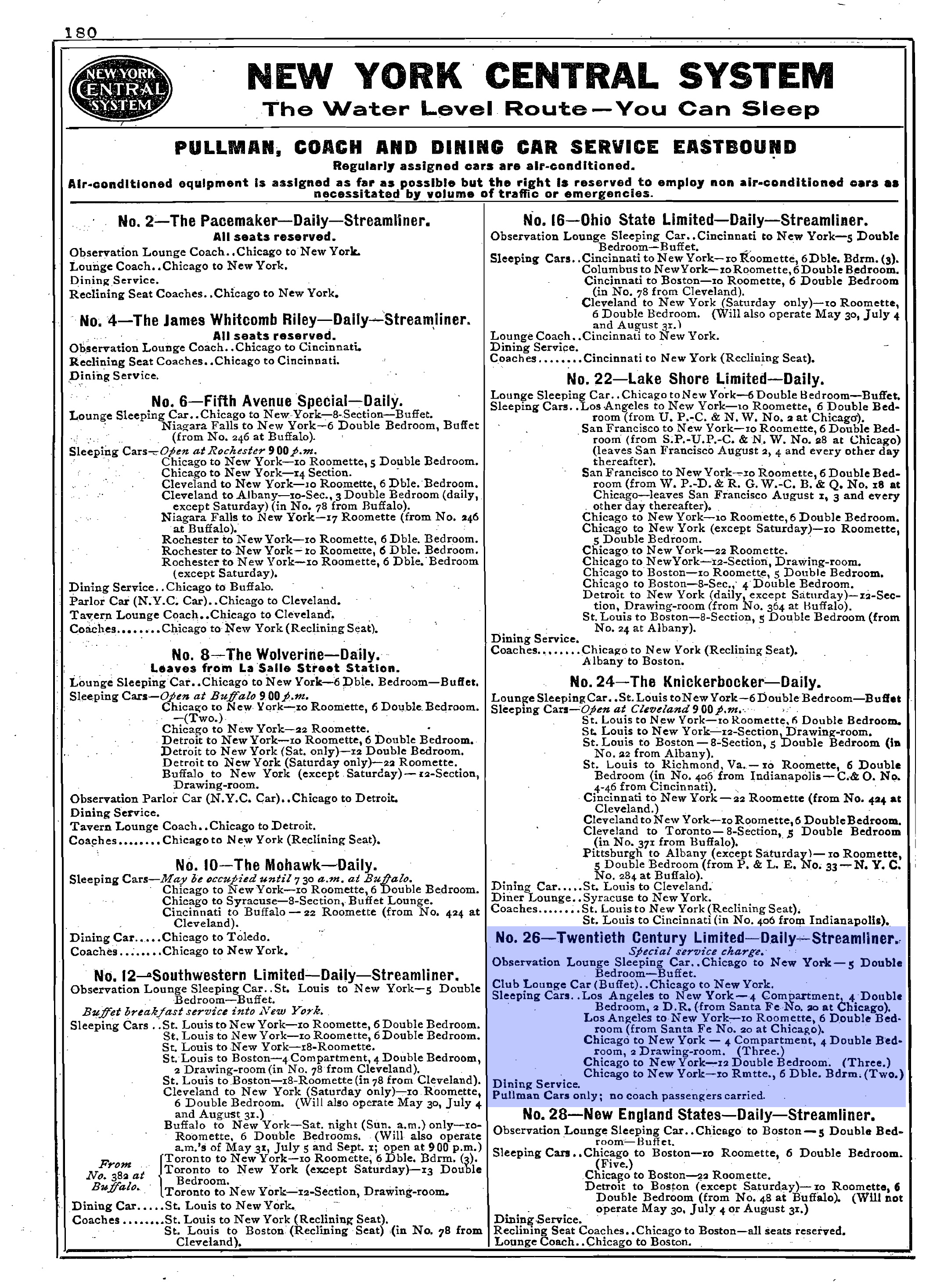

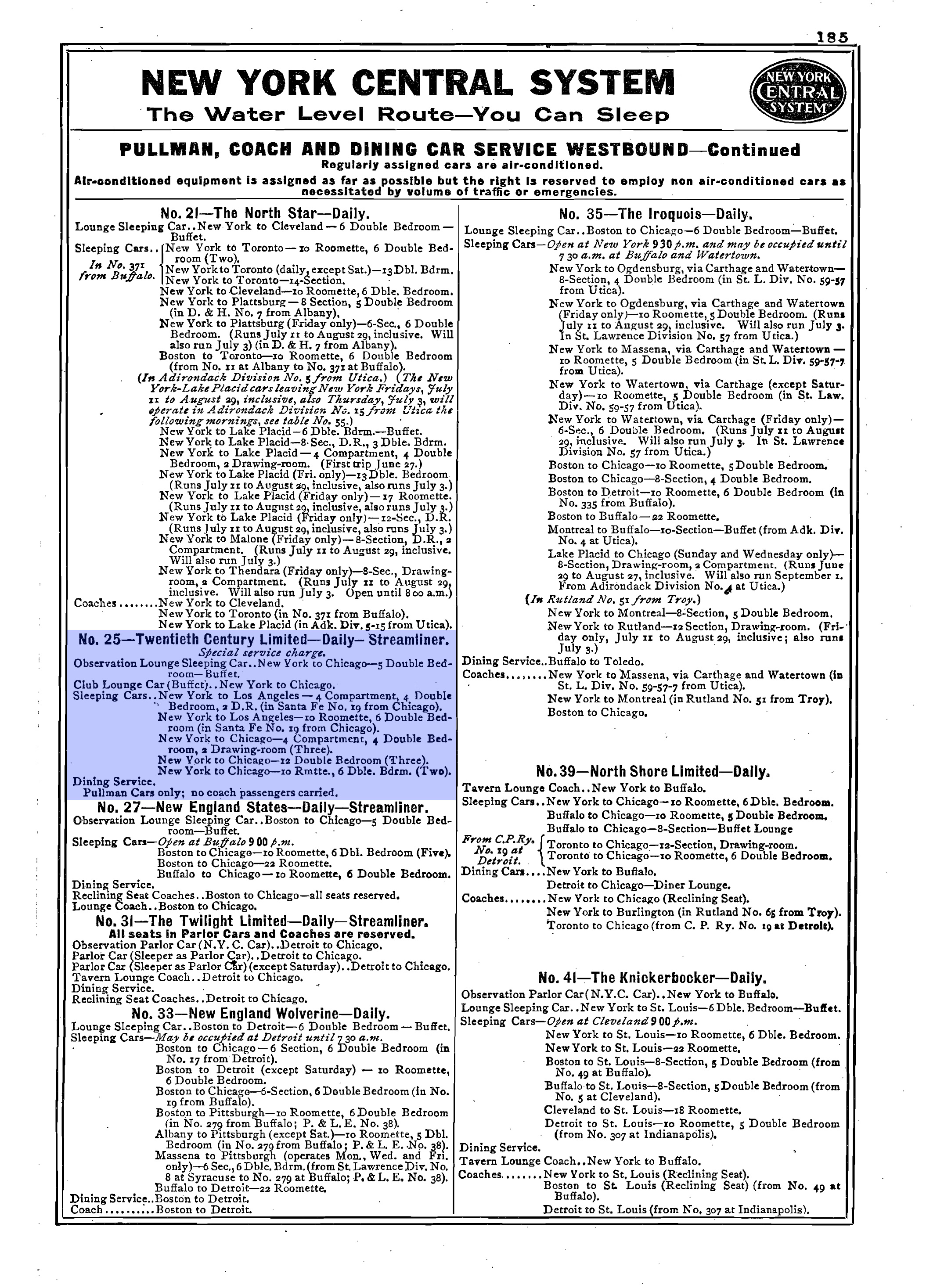

Timetables

(The below 20th Century Limited timetable is dated effective August of 1938.)

| Time/Leave (Train #25) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:00 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 8:00 AM (Ar) | |

| 5:46 PM | 32.7 | 7:00 AM | |

| 7:39 PM | 142.2 | 5:02 AM | |

| 10:05 PM | 289.6 | ||

| 12:25 AM | 435.9 | ||

| 727.6 | 7:30 PM | ||

| 7:26 AM | 954.5 | 3:10 PM | |

| 8:00 AM (Ar) | 961.2 | 3:00 PM (Dp) |

(The below timetable is dated effective June 24, 1956.)

| Time/Leave (Train #25) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:00 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 8:30 AM (Ar) | |

| 5:46 PM | 32.7 | 7:32 AM | |

| 7:45 PM | 142.2 | ||

| 7:15 AM | 954.1 | 3:59 PM | |

| 7:45 AM (Ar) | 960.7 | 3:45 PM (Dp) |

(The below timetable is dated effective April 30, 1967 just prior to the train's cancellation.)

| Time/Leave (Train #25) | Milepost | Location | Time/Arrive (Train #26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6:00 PM (Dp) | 0.0 | 9:30 AM (Ar) | |

| 6:46 PM | 32.7 | 8:34 AM | |

| 8:43 PM | 142.2 | 6:33 AM | |

| 10:56 PM | 289.5 | ||

| F 5:55 AM | 727.1 | F 9:10 PM | |

| F 7:59 AM | 860.2 | F 7:20 PM | |

| F 7:25 AM | 875.2 | F 5:59 PM | |

| F 8:16 AM | 934.6 | F 5:06 PM | |

| 8:42 AM | 954.1 | 4:46 PM | |

| 9:00 AM (Ar) | 960.7 | 4:30 PM (Dp) |

The work, of course, was closely monitored by Dreyfuss himself and the Hudsons became one of the most endearing streamlined steam designs ever conceived.

They featured a gunmetal/aluminum livery to catch the eye and match the rest of the consist while the subtle, yet unmistakable sheathing allowed the running gear to remain exposed for everyone to witness the power of the locomotive in motion. Finally, the curves and angles made the Hudsons appear in motion even when they were not!

The "Lookout Lounge" brings up the tail-end of New York Central's crack, All Pullman "20th Century Limited" in this staged scene by staff photographer Ed Nowak in the fall of 1948. A typical consist during this era, powered by E7's, included the pictured sleeper-buffet/lounge-observation (featuring a raised floor with three double seats and five double bedrooms), two 10-roomette/6-double bedrooms, two 12-double bedrooms, three 4-compartment/4-double bedrooms/2-drawing rooms, two through sleepers to Los Angeles (via the Santa Fe), club lounge-buffet, full-length diner, and an RPO. How rail travel was meant to be...

The "Lookout Lounge" brings up the tail-end of New York Central's crack, All Pullman "20th Century Limited" in this staged scene by staff photographer Ed Nowak in the fall of 1948. A typical consist during this era, powered by E7's, included the pictured sleeper-buffet/lounge-observation (featuring a raised floor with three double seats and five double bedrooms), two 10-roomette/6-double bedrooms, two 12-double bedrooms, three 4-compartment/4-double bedrooms/2-drawing rooms, two through sleepers to Los Angeles (via the Santa Fe), club lounge-buffet, full-length diner, and an RPO. How rail travel was meant to be...The signature trait of the steamer was its bullet nose and

distinctive protruding fin, which wrapped vertically all of the way up

the nose and was given a flushed finish to the back of the cab. All in all, everything from the leading Hudson to

the sleeper observation, inside and out, exuded speed, elegance, and

royalty.

Their appearance became one of the most endearing memories from the streamlined era and the locomotives' bullet-nosed, clean look continues to inspire in today's logos and corporate designs.

Aside from their good looks, however, the J3a's were capable, powerful machines that featured many of the latest technologies in steam power from Elesco feedwater heaters to roller-bearings mounted on all locomotive and tender axles.

Consist

According to SteamLocomotive.com they provided 20% more power than their earlier counterparts and could cruise at speeds of up to 85 mph.

Unfortunately, the beauty of these locomotives lasted for only about a decade, except for #5450 which suffered a boiler explosion in September of 1953. After World War II the other nine lost their shrouding between March of 1946 December of 1947. None were ever saved for posterity.

Despite its declining financial health, the New York Central maintained its flagship service to high standards until the end. Here, the "20th Century Limited" departs Chicago's LaSalle Street Station in June, 1967. Six months later the train was canceled.

Despite its declining financial health, the New York Central maintained its flagship service to high standards until the end. Here, the "20th Century Limited" departs Chicago's LaSalle Street Station in June, 1967. Six months later the train was canceled.Final Years

The 20th Century was built for style and stardom (the train conveyed the New York lifestyle) and it tailored perfectly to young executives and “new money.” So popular was the train that the Central often dispatched two consists, one in each direction.

Both the PRR and NYC misread the boom in WWII traffic and spent millions of dollars upgrading their respective passenger fleets as rail travel began its slow recession in the 1950s. While the Central purchased more in upgrades than the Pennsy it was also the first to call it quits with its flagship.

In 1967, the same year that the PRR dropped “All Pullman” status on its Broadway Limited the NYC discontinued its 20th Century Limited at year's end, an ominous sign of just how derelict the passenger rail market was by that time. While arguments will persist over which train was most regal both reigned supreme in the east.

Each train’s renowned

status can be measured purely on how well it is remembered; after

decades since each left the rails they remain well-documented in books, conversation, and for those who study the industry's history.

Sources

- Doughty, Geoffrey H. New York Central's Great Steel Fleet, 1948-1967 (Revised Edition). Lynchburg: TLC Publishing, Inc., 1999.

- Schafer, Mike. Classic American Railroads. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1996.

- Solomon, Brian and Schafer, Mike. New York Central Railroad. St. Paul: Andover Junction Publications, 2007.

Recent Articles

-

Virginia Wine Tasting Train Rides

Jul 07, 25 10:45 PM

Wine tasting trains in Virginia provide just that—a unique experience that marries the romance of rail travel with the sensory delights of wine exploration. -

Vermont Wine Tasting Train Rides

Jul 07, 25 10:39 PM

Known for its stunning green mountains, charming small towns, and burgeoning wine industry, Vermont offers a unique experience that seamlessly blends all these elements: wine tasting train rides. -

Indiana's Whiskey Train Rides

Jul 07, 25 10:31 PM

Whether you're a local resident or a traveler looking to explore Indiana from a unique perspective, hopping on a whiskey train ride is a journey worth considering.