Railroads In The 1930s: Facts, Statistics, Photos

Last revised: February 24, 2025

By: Adam Burns

Railroads entered the 1930s with great uncertainty following 1929's stock market crash which caused a nationwide economic collapse.

It resulted in major systems like the Rock Island (1933), Milwaukee Road (1935), Erie (1938), Chicago & North Western (1935), and New York, New Haven & Hartford (1935) all entering receivership. Only the strongest managed to avoid bankruptcy.

The industry was facing a terrible dilemma as both freight tonnage and the passenger market were down significantly. The traveling public was abandoning trains for two primary reasons; the economy and the automobile's affordability.

In an attempt to reignite interest, Union Pacific and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy devised the streamliner concept.

These fast, colorful trainsets were an instant sensation and the entire industry took notice. By the 1940's, many of the largest railroads were jumping on board, forever changing rail travel.

History

The winds were also shifting in other ways. During the 1920's, diesel locomotive usage was growing. At the time, this new form of motive power was largely confined to switcher and secondary assignments.

Then, in 1935, Electro-Motive unveiled a main line variant for passenger service. It later expanded upon this with 1939's FT model for freight service.

While initially skeptical most railroads which tested the demonstrator set were left completely mesmerized. The days of steam were numbered...

Photos

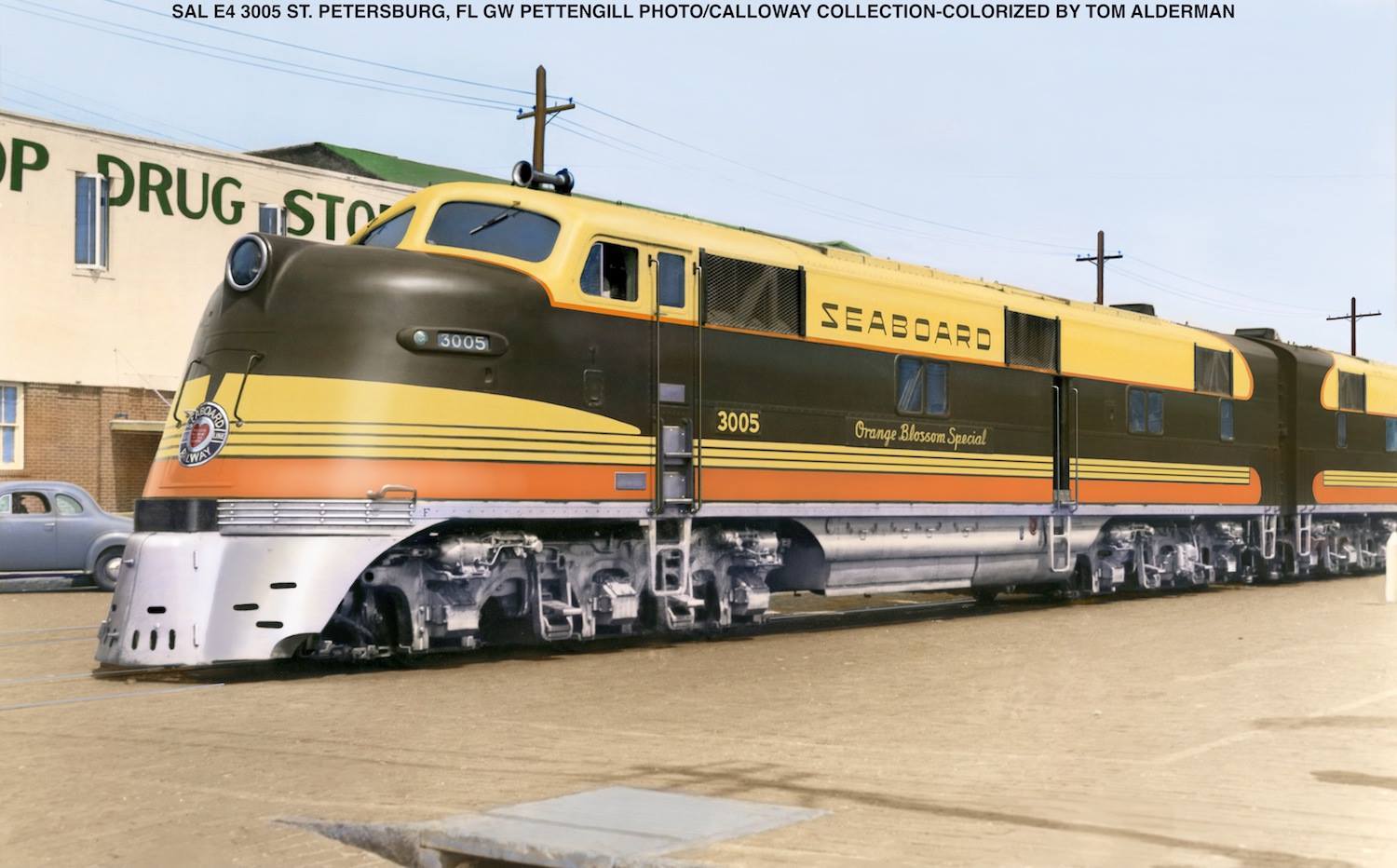

Seaboard Air Line E4A #3005 with the "Orange Blossom Special" at St. Petersburg, Florida, circa 1939. The railroad had first acquired these locomotives for its new "Silver Meteor" streamliner which also debuted that year. It was the South's first and proved immensely successful. G.W. Pettengill photo/Warren Calloway collection/Tom Alderman colorization.

Seaboard Air Line E4A #3005 with the "Orange Blossom Special" at St. Petersburg, Florida, circa 1939. The railroad had first acquired these locomotives for its new "Silver Meteor" streamliner which also debuted that year. It was the South's first and proved immensely successful. G.W. Pettengill photo/Warren Calloway collection/Tom Alderman colorization.Competition

During the 1920's, railroads remained the dominant mode of transportation. However, their monopoly was in jeopardy. Historian John Stover notes in his book, "The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads," in 1895 a grand total of four automobiles were manufactured in the United States.

But then, Henry Ford introduced the assembly line and, coupled with the internal combustion engine's introduction some years earlier, his Model T debuted on October 1, 1908.

The machine's initial price tag of $850 put it within reach for some Americans. However, it was Ford's continued drive to reduce costs which forever changed America.

At A Glance

By 1925 the price had dropped to just $260, making the Model T easily affordable for many.

Despite the nation's relatively poor road conditions the automobile was nevertheless convenient and immensely popular. The public now had the freedom to travel when and where they pleased at little cost.

By 1927, some 15 million had been manufactured and vehicle registrations jumped from 3 million in 1916 to 23 million by 1929. Air travel was also catching on, even though by 1939 this new industry was still in its infancy and transported only 2% of commercial passenger traffic.

Rail Travel Decline

Railroading's losses in the passenger market were staggering and immediate. In 1916 the industry handled roughly 1 billion travelers. This number had declined to just 700 million by 1930 and would be further reduced by another 35.7% during the next decade.

Even by 1929 railroads realized the future of rail travel was bleak; that year they handled 34 billion passenger miles compared to the automobiles' 175 billion.

Buses were a particular threat; they already controlled 15% of the commercial passenger market by 1929, a number which jumped to 38% by 1950.

Such stiff competition was already well understood by the dying interurban industry as it was the first to feel these effects. These electrified, rapid transit railroads sprang up in the 1890's and culminated into a 15,000-mile network by 1916.

Unfortunately, their dependence on the most fickle [and unprofitable] of traffic, commuters, along with general poor construction, insignificant rate of return, and an extremely high operating ratio (as of 1924, it averaged 85%) resulted in their steep decline by World War I.

By the early 1930's the industry was no longer recognizable in its original form. Most which did survive to World War II did so as short line freight railroads.

As Dr. George Hilton and John Due's point out in their authoritative book, "The Electric Interurban Railways In America," had Ford's Model T been unveiled just a few decades sooner, this unique aspect of American transportation would likely have never existed.

For traditional railroads, so accustomed to handling most of the country's freight and passengers, they were unwilling to so easily throw in the towel.

Streamliners

The streamliner era is, of course, the decade's best remembered moment, even in the midst of the Great Depression. It was also the most successful. In terms of rail travel's "Golden Age," streamliners were a relatively late concept.

The movement also received a boost from the unique Art Deco era, which took off during the 1920's. Its form and function could be found in early diesel models like the EA, the M-10000, and the Pioneer Zephyr. It was also employed liberally by interior car designers.

As Mike Schafer and Joe Welsh note in their book, "Streamliners: History Of A Railroad Icon," Union Pacific conceived a radical new concept during the early 1930's; a high-speed trainset utilizing a 600 horsepower distillate engine provided by the Winton Engine Company.

One of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy's new "Zephyr" trainsets is seen here stopped at La Crosse, Wisconsin during the summer of 1939. The "Zephyr's" were a radical departure from anything the public had previously seen. They saw many successful years of a service. Arthur Rothstein photo.

One of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy's new "Zephyr" trainsets is seen here stopped at La Crosse, Wisconsin during the summer of 1939. The "Zephyr's" were a radical departure from anything the public had previously seen. They saw many successful years of a service. Arthur Rothstein photo.What the railroad dubbed simply as, "The Streamliner," was also the work of Pullman-Standard. It's livery featured what Union Pacific called "Canary Yellow" and "Golden Brown," (the former chosen specifically for safety reasons) while accommodations were relatively modest featuring just a 60-seat coach and buffet-kitchen-observation.

Capable of reaching 110 mph it was an immediate success that wowed and stunned the public. Prior to its debut trains had largely been viewed as mundane machines used for transportation between two points.

Shortly thereafter the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy unveiled its Zephyr 9900 (later renamed the Pioneer Zephyr) at Philadelphia's Broad Street Station on April 18, 1934. It was also a three-car articulated design.

The work of the Budd Company (a Pullman competitor), its prime mover was the Winton eight-cylinder 201-A diesel engine capable of 660 horsepower.

The 197-foot train featured a simple, yet elegant, sloped nose to enhance its streamlining features with accommodations including the combined power car/Railway Post Office/mail-storage area, a baggage/coach, and a coach-parlor-observation. The Zephyr held less seating, just 72 paying customers.

However, the CB&Q arguably boasted the much more reliable train since its diesel engine had fewer mechanical issues. It also earned the greatest fanfare during its historic initial run on May 26, 1934.

That day the trainset left Denver at 5:05 AM in anticipation of reaching Chicago later that evening. With an average speed of 78 mph it completed the 1,015-mile trip in just 14 hours, arriving in the Windy City at 7:10 PM.

Just two years after these two pioneering streamliners were introduced the Electro-Motive Corporation unveiled its first stand-alone diesel locomotives.

The 1930's were a fascinating time in locomotive development; steam power was reaching its technological apex with magnificent designs like the 4-8-4, 4-6-6-4, and "Duplex Drive" all in development at that time.

The "Super Power" concept was also in full swing. It describes late era variants, beginning with the 2-8-4, which featured larger fireboxes and super-heaters.

Diesel Locomotives

The term has also been used to include new technological applications such as roller-bearings, mechanical stokers, and outside valve gear. In his book, "Vintage Diesel Locomotives," author Mike Schafer notes General Electric earned distinction as helping design America's first commercial diesel locomotive, Jay Street Connecting #4, manufactured in October, 1918.

The diesel was refined and improved until a fairly robust switcher market, largely controlled by American Locomotive, General Electric, and Electro-Motive, had been established by the 1930's. Then the Electro-Motive Corporation (EMC) took things a step further.

According to the book, "The American Diesel Locomotive" by Brian Solomon, EMC's first main line models were three 1,800 horsepower boxcabs (utilizing two Winton 201-A, V-12 prime movers) unveiled in 1935.

They featured a B-B wheel arrangement and weighed 240,000 pounds; two went to the Santa Fe (famously nicknamed "Amos & Andy" they were used on the "Chief" and operated as a pair, "Diesel Locomotive #1") and one, #50, to the Baltimore & Ohio.

EMC also manufactured two demonstrator units, #511 and #512. Two years later, their nearly identical streamlined cousins were acquired by the Baltimore & Ohio (listed as model EA) and, again, Santa Fe (E1).

As EMC stated in 1925, "We're selling a standard car engineered by us, and bearing a standard price tag." This proved quite true as Electro-Motive dominated the diesel market for the next six decades.

EMD's FT

While these early designs were somewhat successful it was not until the development of Electro-Motive's FT for main line freight service was the industry convinced of the diesel's true capabilities. Freight paid the bills and one by one, FT demonstrator set #103 made believers out of skeptics.

The A-B-B-A set encompassed four, individual locomotives which could produce a combined 5,400 horsepower. Just like the original passenger "E" series models, the FT was gracefully streamlined.

Its primary upgrade was the utilization of a new engine, General Motors' model 567, which made its debut in late 1938.

Variants of this engine remained in production through the mid-1960's. The #103 set embarked on an 11-month, 84,000 mile tour in November, 1939. During that time it operated on 20 Class I railroads and visited 35 states.

Believers in Electro-Motive (and ultimately long-time buyers of its locomotives), the B&O and Santa Fe both tested and purchased the FT. Other notables included Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; Great Northern; Southern Railway; Boston & Maine; Chicago & North Western; and Missouri Pacific.

As Mike Schafer notes in his book, "Vintage Diesel Locomotives," at the zenith of Electro-Motive's dominance the builder controlled a staggering 90% of the diesel locomotive market, worldwide.

As 1940 dawned, diesels and streamliners were the order of day. With new technologies rapidly evolving, America entered World War II on December 7, 1941.

This time railroads were prepared for the onslaught of traffic and no government oversight was needed. Not only did railroads see record freight traffic during this time but also a passenger renaissance. Without the railroads, victory in World War II would not have been possible.

Contents

Recent Articles

-

Indiana Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 20, 25 12:09 AM

Indiana has always been an historically important state and once home to thousands of miles of railroads. Today, several museums preserve this heritage. -

Georgia Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 19, 25 11:55 PM

The state of Georgia has a long history with railroads, from an importance during the Civil War to even today. Today, several museums preserve its rich history. -

Florida Railroad Museums: A Complete Guide

Apr 17, 25 04:48 PM

Florida is home to many railroad museums preserving the state's rail heritage, including an organization detailing the great Overseas Railroad.